For the first time in its 70-year history, the Addicks Dam, one of two earthen structures west of Houston designed to protect the Bayou City from catastrophic flooding, is spilling over. (At this time, the Army Corps of Engineers is not anticipating a breach, maintaining that the dam itself remains solid.)

At an early morning news conference Tuesday, the Army Corps of Engineers described the “uncontrolled release” put everything downstream along Buffalo Bayou—dozens of subdivisions, the Memorial Villages, Memorial Park, River Oaks, and downtown Houston—into “uncharted territory.”

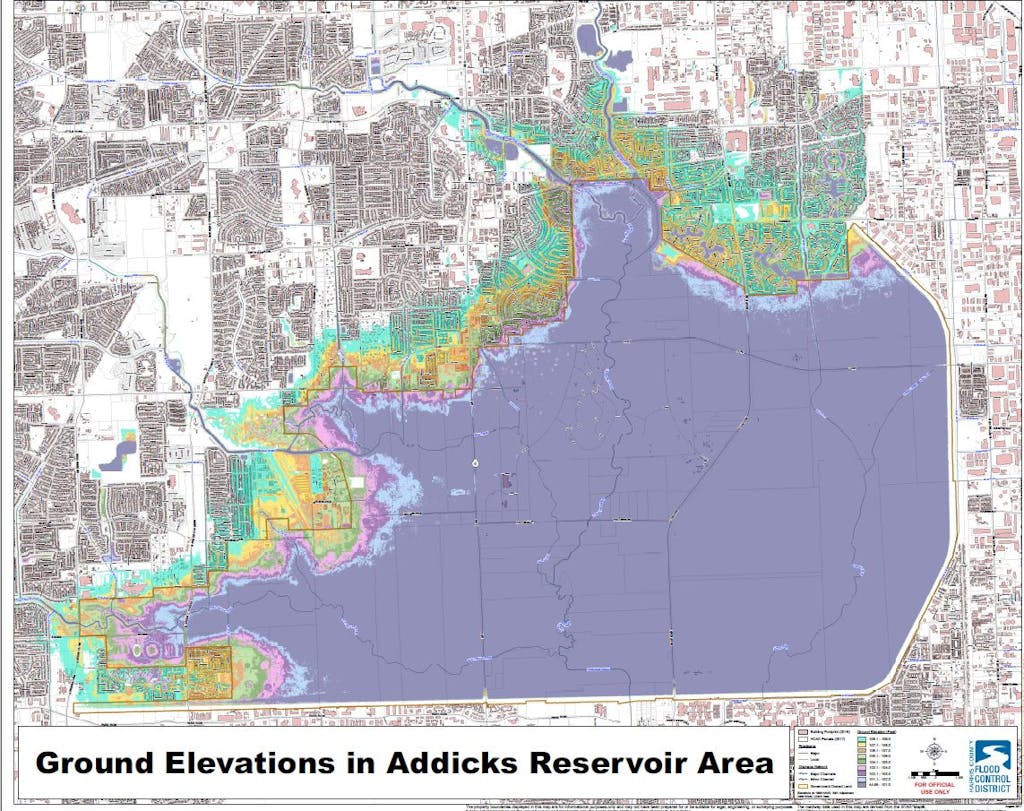

Although Buffalo Bayou flooding was subsiding in the above map’s green, yellow, and purple areas, the spillage from the dam will cause water to rise again. How much? “This is not going to happen fast,” said Harris County Flood Control District meteorologist Jeff Lindner. “This is a slow rise.”

Monday night, officials released lists of dozens of subdivisions in the area that were considered in jeopardy from these reservoirs. Here is the Harris County list. Here is the Fort Bend County list of evacuation orders, many of which are threatened by record Brazos River flooding rather than the dams.

Officials said the following subdivisions were now vulnerable to flooding, and suggested evacuation—even for those in two-story homes:

- Twin Lakes

- Eldridge Park

- Lakes on Eldridge

- Independence Farms

- Tanner Heights

- Heritage Business Park

Some 3,000 structures were threatened, Lindner said, and about 2,000 more were already inundated with as much as five feet of water. Flooded homes and businesses were expected to remain underwater for as long as a month.

“The biggest challenge that we face right now is seeing how this flow interacts with our system,” he said, “and where the water will go as it comes out of the north end of the Addicks Reservoir.” He hoped that “some portion” of the released waters could meander over into the White Oak Bayou watershed, which could easily handle the runoff.

At 10 a.m., at I-10 and Barker Cypress, heroic out-of-towners were plucking evacuees from the chest-deep flood as they fled a half-dozen apartment complexes. A KPRC-TV reporter asked one boat captain how many people were trapped in the area. “Thousands,” he said, as he headed back into the waters.