To the cops who patrolled Dallas’ richest and most exclusive neighborhoods throughout the 1990’s, Mitch Shaw and his cute girlfriend, Jennifer Dolan, must have looked like a couple of rubes. For one thing, they cruised through the neighborhoods in a turquoise Toyota Tercel. Turquoise! Jennifer always drove, usually with her window down, her magnificently teased hair and dangling costume earrings fluttering in the wind. Although no one would have called Jennifer a knockout, she had a big, inviting smile, and she clearly knew how to handle herself around men. When a Dallas police officer stopped Jennifer and Mitch a couple of years ago to ask why she kept tooling up and down one particular mansion-lined lane, Jennifer gave the officer a little wink and said in a voice as sweet as syrup, “Officer, we live in a little apartment, and sometimes we like to look at big, pretty homes. Is there anything wrong with that?” Then she pursed her lipstick-red lips around a straw and took a drink from a big cup of Diet Coke that she had wedged between her thighs.

If the officer was able to take his eyes off Jennifer—and, in all honesty, it was an effort to not look at her, especially when she wore one of those bras that pushed her breasts together—then he would have glanced over and seen a slightly pudgy, unmuscular young man with soft brown eyes, long eyelashes, thinning dark hair, and a gentle, almost perplexed expression on his face. Mitch Shaw was not exactly a threatening figure. His friends said he was a computer geek who spent most of his time creating Web sites on the computer that sat on the kitchen table of the one-bedroom apartment in far north Dallas that he shared with Jennifer. For relaxation, he watched Jeopardy, dabbled in abstract painting, played with his tabby cat, Sweet Pea, and took Jennifer to the Galleria, where they wandered through the stores and ate fast food down by the skating rink. They looked like so many other young couples you see at the mall, couples still trying to find their footing in life, the type who often drive through rich neighborhoods at the end of the day so that they can dream about what their lives might be like someday. As the wide-eyed Jennifer exclaimed to the police officer that day, “Just look at these homes with all these big columns. They’re bigger than Ramada Inns.”

Actually, Mitch and Jennifer were not that interested in the way those homes looked—not from the outside, anyway. According to statements that Jennifer would later give to Dallas police detectives and subsequently confirmed to me, she would often park the Tercel on a side street with little traffic and watch as Mitch, who usually wore a rumpled T-shirt, baggy shorts, and tennis shoes for their evening drives, put a black baseball cap backward on his head, pulled on a pair of gloves, and then snapped a fanny pack around his waist that was filled with just three items: a flashlight, a screwdriver, and a pack of cigarettes.

“Be careful, honey,” Jennifer would always say, leaning across the seat and giving him a kiss.

“Don’t you worry,” he would reply. And then Mitch would jog toward one of the mansions, scale the outside wall or gate, slip unnoticed through the back yard, expertly knock a hole in the window of the master bathroom, hoist himself through, and meticulously begin hunting for jewelry. He’d pick the locks of cabinets, rifle through closets, pull up carpets, and then make spectacular last-second getaways, racing back out the window just as police helicopters and squad cars were closing in.

Professional jewel thieves aren’t supposed to exist anymore. Confronted with a state-of-the-art combination of electronic locks, infrared motion detectors, and hardwired detectors on doors and windows, most criminals are lucky to get inside a wealthy person’s house, let alone have the time to figure out where the jewels are. But the police are convinced that Mitch Shaw, who’s now 31, was one of the shrewdest and most daring jewel thieves of our time and that Jennifer Dolan, who’s now 26, acted as his “wheelman,” dropping him off and then picking him up at prearranged locations near the targeted homes, so confident a driver that she’d wave flirtatiously at the cops as she drove away with Mitch crouched on the floorboard.

Mitch is the lead suspect in the break-ins of some of Dallas’ best-guarded homes over the past decade. Police detectives believe that he snatched jewels from the lavish residences of such society-column notables as Nancy Brinker, the wife of restaurateur Norman Brinker and the founder of the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation; Clarice Tinsley, a popular Dallas television anchor; and the flashy charity ball hostess Sharon McCutchin. His crowning achievement came on a rainy night in January 1998, when Jennifer dropped him off just down the street from the Preston Hollow–area estate of Dallas billionaire Harold Simmons, whose wife, Annette, is renowned for her magnificent collection of jewelry. The 12,000 square-foot Simmons home seemed impenetrable. It was guarded 24 hours a day by an off-duty trooper from the Department of Public Safety, who walked the grounds twice an hour. In the back yard was a German shepherd guard dog. Wired to the windows and doors was an alarm system that was designed to go off even if the window panes rattled too loudly.

But Mitch made friends with the dog, avoided the DPS officer, deftly popped out two window panes in the master bedroom, found a key in the powder table that fit a locked closet, and then used his screwdriver to pry open five locked drawers, each one containing jewelry. He dumped the jewelry into a pillowcase and raced back to the Tercel, where Jennifer was sitting patiently, slurping on a Diet Coke. Back at their apartment, they dumped Mrs. Simmons’ jewels on their bed—nearly two hundred pieces, worth at least $1 million. Mitch and Jennifer had just pulled off the biggest jewelry heist of a residence in Dallas history.

Until now, the story of the duo’s improbable crime spree has never been told—and even those who know the story still have trouble believing it could be true. How could two young people, dreamy-eyed with love but amateurs in crime, execute the kind of heists that would daunt even the most highly skilled European cat burglars? How did they elude the cops for so long? Were they just lucky, able to evade police officers because they looked like two bumbling characters out of a lowbrow comedy? Or was there something far more ingenious about their methods and manners?

“It’s like a dream, thinking about what we did,” Jennifer told me not long ago, speaking publicly for the first time about her life with Mitch. “Here we were, living in a little $525-a-month apartment—it was all we needed, really—and then we’d go out at night and live this other life. It was sort of romantic, you know? Someone told me it’s like we were Bonnie and Clyde.”

Mitch Shaw is not one of those thieves who grew up on the wrong side of the tracks. He is a descendant of a family that once was as well known in Dallas as the families whose jewelry he is now accused of stealing. His great-grandfather was a respected Dallas judge named C. V. Compton who owned a grand three-story mansion on Lakeside Drive, the most elegant street in Dallas’ Highland Park area, where most of the well-to-do families lived. The judge’s three daughters were presented as debutantes to Dallas society. One daughter, Clairine, married a successful young lawyer named Thomas Mitchell Shaw, and their second son, Thomas Mitchell Shaw, Jr., was still a teenager when he met Melanie Trauman, a striking young woman who had moved to the Highland Park area with her mother. She became pregnant, a marriage was quickly arranged, and in 1968 she gave birth to Thomas Mitchell Shaw III.

Many of Mitch’s family members—including Melanie’s own mother, Nancy Wiener, who now lives in California—told me that Melanie, who had ferocious social ambitions, went for Shaw because she thought there was money in his family. But Mitch’s father received little inheritance. After graduating from Southern Methodist University with a degree in accounting, he went to work for the state comptroller’s office, and when Mitch was still a toddler, Melanie asked for a divorce and eventually moved to Houston, where she married a successful real estate developer and had her photo taken for a 1974 Town and Country magazine story about the boom times. (She posed in an off-white Geoffrey Beene coat and beret in front of the Houston skyline.) Mitch remained in Dallas with his father and barely saw his mother.

Mitch’s father married again—his new wife, Nancy, was a former high school classmate—and they moved to a pleasant but not ostentatious neighborhood in northwest Dallas. According to Nancy, who gave birth to two daughters after marrying Mitch’s father, Mitch was a shy child who played the piano and the guitar and took art lessons at school. He did have mild dyslexia and briefly took Ritalin for a minor attention-deficit disorder, “but he was really no problem,” she told me. “He was this physically gorgeous boy who liked going on weekend camp-outs with his father, loved the Dallas Cowboys, and loved to swim laps in our backyard pool. We called him a little dolphin.”

Throughout most of his teenage years, Mitch stayed mostly to himself, quiet and introspective, the kind of kid who rarely had photos taken of him for the high school annual. Eventually he quit school and received his GED. Because he loved abstract painting and could knock off remarkable imitations of Picasso masterpieces, some of his friends thought he might grow up to become an artist. His biggest love, however, was the computer. Long before the Internet became popular, he worked on his computer into the late hours, teaching himself to create graphic designs and to write HTML code, the computer programming language used to build Web sites.

Then, in 1987, Mitch’s father began to get horrendous headaches and was diagnosed with an incurable brain tumor. For the first time, Mitch, who was then nineteen, got into some trouble. He was arrested and given a year’s probation for breaking into an automobile and stealing a camera. Mitch was hardly a competent criminal: When he hocked the camera at a pawnshop, he wrote down his correct name and address on the pawn slip, which led to his easy arrest once the camera was reported stolen. “We wondered if Mitch was just so angry at not having his mother around and seeing what was happening to his father that he decided to lash out at something,” said his stepmother, Nancy. “We didn’t know what made him do it, and we couldn’t imagine that this was something he planned to do again.”

Indeed, one act of teenage rebellion does not a professional jewel thief make. But in 1990, a year after his father died, a friend introduced 21-year-old Mitch to a cute, sassy teenager with big brown eyes and soft pouty lips. Her name was Jennifer Dolan. And Mitch fell so crazy in love that he found himself willing to do just about anything.

As the guys from Mitch’s neighborhood liked to say, Jennifer Dolan was the kind of girl who gave you an instant buzz in the gonads. She was a 16-year-old who acted 26. She smoked, she drank, and she liked to stay out late. “I thought she was going through a stage and that she would grow out of it,” her mother told me. “Well, I figured wrong.” It was hard to believe that the two would ever get along. Compared to Mitch and his blueblood background, Jennifer was middle-class: Her widowed mother supported the family by operating a couple of low-income apartment complexes. Mitch liked spending his evenings reading computer books; the gregarious Jennifer prided herself on getting into bars with her fake ID. Many of Mitch’s family members have not forgotten their first sight of Jennifer, at a Christmas luncheon thrown by one of Mitch’s austere great-aunts. Jennifer sat at the end of the table, her body curvy and a little plump, her hair wild and wavy, her eyes rimmed with thick black eyeliner. The bracelets on her arm rattled each time she lifted her fork.

Mitch was infatuated with her. “I think, considering the lonely times he had been through, he liked having a young, frolicsome, pretty little thing who was impressed by him, who let him take care of her,” said Nancy Wiener, Mitch’s grandmother. Every afternoon, Mitch picked up Jennifer at Lake Highlands High School in northeast Dallas, where she was a freshman, and took her shopping at the Galleria. Dipping generously into his inheritance money—he reportedly had received $60,000 after his father’s death—he bought what she asked for, usually colorful Fila sweatsuits and more costume jewelry than she could possibly wear. “I loved big fake earrings, the bigger the better,” Jennifer matter-of-factly told me, nibbling on a club sandwich and drinking a Diet Coke at a Bennigan’s restaurant. “That’s what people don’t understand about me. I didn’t want to wear big old socialite jewelry. One day Mitch gave me a fifteen-hundred-dollar Rolex watch, but I liked my fake thirty-dollar Rolex better because it was flashy and had all these fake diamonds embedded in it. So I took the plain Rolex back to the store.”

When she was seventeen, Jennifer dropped out of high school and moved into Mitch’s apartment. “There was nothing I could do to stop her,” said her mother. “And in a way, I couldn’t blame her. Mitch treated her like a queen. He gave her money, which she’d never had before. If she got mad at him and moved back home, he’d come over and stand out in our yard all through the night, tapping on her bedroom window, begging her to come back.”

Jennifer told me that she and Mitch would argue over her desire to go out with her girlfriends and “um, get in a little trouble”—her code phrase for meeting another guy. “Mitch would ask me why couldn’t I just be with him all the time, and I’d tell him I didn’t want to sit around at nights watching him work on his computer.” After one argument, she dramatically pulled off some diamond jewelry Mitch had given her, tossed it down the garbage disposal, flicked on the garbage disposal switch, and squealed away from the apartment complex in her car. When Mitch began paging her over and over to persuade her to come back, Jennifer stopped the car, threw the pager out in the street, and then ran over it.

Yet she always returned. “I put him through some hell, but he cared what happened to me,” she told me. “There was no one sweeter than Mitch.” Still, like so many other lovelorn young men wanting to win over a girl, Mitch clearly felt the need to do something—something that would add a dramatic new dimension to his personality, something that would make Jennifer’s eyes shine with admiration.

But was it really possible that Mitch Shaw the computer nerd thought he could turn himself into the dashing Cary Grant character from To Catch a Thief? His grandmother told me he didn’t even dance well. “The one physical talent he had was his ability to type very quickly on his computer keyboard,” added a close family friend. “This was not someone you could ever envision climbing trees and jumping over walls and entering houses that had armed guards. I promise you, the Mitch I knew was scared of my medium-sized dog.”

In truth, the possibility of becoming a jewel thief might have been nothing more for Mitch than a Walter Mitty–esque dream had it not been for a middle-aged man who lived in Mitch’s old neighborhood and who from time to time had stopped by the neighborhood park where teenagers congregated. The man was distinguished-looking, easygoing, and always interested in the kids’ lives. He also possessed one other trait, according to Dallas Police detectives who spoke to me: He had a rather extensive knowledge of Dallas’ criminal underworld. The man’s own father had been a mobster during the fifties gangland wars over the Dallas gambling rackets. The man himself had been sentenced to the penitentiary for five years in 1977 after fatally shooting another man who, depending on whose version of the shooting you want to believe, was either a renegade heroin dealer or a police informant.

Although by all accounts the man’s violent days were behind him, he remained a subject of great curiosity to the kids at the neighborhood park. Many of them had heard that he had married into a Mafia family. Others had heard that he was a fence who would purchase stolen jewelry and then have it cut up and resold to dealers he knew on the East Coast and perhaps as far away as Europe, people who didn’t particularly care where the jewelry came from.

It is no secret that every good jewel thief needs a fence; otherwise, the thief might end up unloading his merchandise at pawnshops for pennies. What’s often forgotten is that every good fence needs a thief; otherwise, he won’t have any jewels to sell. Was it possible that the man in the neighborhood came to the park to recruit a thief? Had he heard about Mitch’s earlier run-in with authorities over the stolen camera and decided this was a kid he could groom? Did Mitch, in turn, see in this man his lucky opportunity to create a new life for himself?

When I spoke to the man—who is now 48 and has not been charged with any crime related to the jewel heists—he stated that he was working in “private business” and that he didn’t go to the neighborhood basketball court and that he had never fenced jewelry. “What in the hell would I do with all that jewelry? I have trouble enough keeping up with my Seiko watch,” he said with a good-natured chuckle. He said he did become friends with Mitch but not for nefarious reasons. “I felt sort of sorry for the kid, with him losing his dad and his mom being gone,” the man said. “I talked mostly to him about his computer work, which is about the only thing he liked talking about.”

But detectives believe that the man from the neighborhood taught Mitch how to break into homes and then offered to buy whatever jewelry Mitch brought him. If so, the man saw a talent in Mitch that no one else did. Indeed, Mitch turned out to be a precocious burglar. The police believe he first broke into smaller homes around his old neighborhood—“training homes,” he called them. His modus operandi was to enter a home through a bathroom window, in part because he had learned—or had been taught—that motion detectors are rarely installed in bathrooms. With his screwdriver, he learned to crack the window panes almost as noiselessly as a chef cracks an egg, then he carefully would pull out the shattered pieces until he had a hole big enough to crawl through. Sometimes, he’d remove the weather stripping and take out the entire bathroom window to get in. And more often than not, he’d get lucky and discover that the homeowners had simply neglected to turn on their alarms.

The only problem for Mitch was that he couldn’t find a good wheelman he could trust. Initially, he used a couple of buddies from the neighborhood, but they tended to panic and flee if they saw police officers, forcing Mitch to make his getaways on foot through back yards and alleys. Mitch knew that if he was ever going to move up to the elite Dallas neighborhoods, where he would face private security guards and regular police patrols, then he was going to need a wheelman who not only was composed enough to wait for him as long as was necessary at the pickup locations but also could handle any questions from the cops and, if Mitch was being pursued, would be willing to floor the accelerator once Mitch was in the car and make a run for it.

But instead of finding a professional, Mitch made a decision that must have made the man in the neighborhood shake his head in disbelief. He asked Jennifer to join him.

Perhaps he thought it was such a romantic notion: the two of them embarking on a great adventure, stealing jewels from rich people who probably had the insurance to cover their losses. Or maybe he thought that if he and Jennifer created a life together as criminals, she’d be less likely to go out with her friends to meet other guys. Whatever the reason, he had made a far more brilliant choice than maybe even he realized. With her big hair, her always-skillful makeup job, and her manicured nails tapping the steering wheel as she listened to rap music, Jennifer would drive around a neighborhood after dropping Mitch off, oohing and aahing at the mansions, and always circling back to the pickup spot right on time. In our conversations Jennifer remained coy about many aspects of her relationship with Mitch, but when I asked her if she had been scared about becoming Mitch’s wheelman, she gave me an almost nostalgic smile. “Oh, no, it was so exciting. And Mitch always told me it would be so easy.” I realized later that what Mitch had said to Jennifer was almost exactly what Clyde had said to Bonnie in the 1967 movie version of their lives. “Don’t worry about nothing,” Clyde proclaimed about the bank robbery he was planning. “This is going to be the easiest thing in the world.” Compared to his more infamous predecessor, however, Mitch was very, very cautious. Because he hated violence, he refused to carry a gun—he used to tell Jennifer that he wished there were laws banning guns—and he refused to burglarize a home unless the occupants were gone, so there would be no possibility of his getting shot. He and Jennifer would drive through a neighborhood night after night, studying a house, looking to see if certain lights always remained on (a giveaway that the homeowners were out of town). He’d get out of the car and circle the house on foot, peering through windows to see if the beds were made; he’d even peek through mail slots to see if mail was scattered on the floor.

Occasionally, he’d knock a hole in the window and then retreat, sitting in a dark corner of the yard to see if police officers would come or if a light would turn on inside the house. If he heard a phone inside the house ringing soon after making his opening in the window, he’d leave, his assumption being that he unknowingly had tripped an alarm and that the security company was calling the homeowners. And once inside, he never ventured past the bathroom or closets if he thought a motion detector was on in the hallway.

Yet for all his caution, Mitch could be almost incomprehensibly gutsy. Police officers almost never encounter professional jewel thieves anymore, because stealing jewels takes time and time increases the burglar’s risk exponentially. The typical burglar today smashes through a door or window, grabs whatever portable merchandise he can carry, and then lumbers away. In dollars, the average value of the haul in a residential burglary in Dallas totals no more than $3,000. But Mitch was unique. He went after only good jewelry (he usually left the costume jewelry behind), and he loved going after well-known Dallas residents. Based on conversations with Jennifer, the police believe that he burglarized the mansion of restaurant entrepreneur Norman Brinker and his wife, Nancy, twice in one month in 1992 while they were away at their Florida home, and he broke into the home of local television anchor Clarice Tinsley in 1993 when she was out of town. On that occasion he not only took her jewels but also grabbed as a special present for Jennifer a glittery sequin-encrusted denim jacket that Tinsley had purchased at a Dallas AIDS benefit. The police also believe that in 1996, after Dallas socialite Sharon McCutchin had been photographed for the High Profile section of the Dallas Morning News wearing a gigantic diamond ring and gold earrings the size of miniature football helmets, Mitch broke into her and her husband’s Mediterranean-style villa in the Preston Hollow estates area, getting away with some of her best pieces.

In 1993 the Dallas police department set up a task force to investigate the North Dallas jewelry heists and added extra patrols in the neighborhoods where the burglaries were taking place. They got close to Mitch a couple of times, but they never knew it. Once, just as Mitch found two $100,000 diamond-studded Rolexes and $10,000 in cash during one burglary, he heard a siren coming down a street at the back of the house. Sensing his escape route was cut off, he quickly changed into an all-white tennis outfit he had found in the closet, stuffed the watches and cash down the front of his underwear, dashed around to the front of the house, and then trotted right down the middle of the street, as if he were one of the neighbors out for an early-evening jog. No one looked twice at him: Who would have expected a burglar to be dressed in tennis whites?

On another occasion he was inside a North Dallas home when he heard the sound of an approaching police helicopter along with the sirens of squad cars. With the jewels in hand, he headed out of the house, raced to the next-door neighbor’s yard, threw off his clothes except for his boxer shorts, and jumped into the swimming pool. As the police helicopter flew over him, Mitch swam back and forth, back and forth—still, to use the words of his stepmother, the little dolphin. The cops in the helicopter mistook him for the homeowner out for an evening swim—and flew off to look elsewhere. As more cops converged on the neighborhood, a smiling Jennifer maneuvered her way past them in the Tercel, parked at the pickup spot, and waited until a wet-haired Mitch leaped into the car.

If the police are to be believed, Mitch was doing at least a dozen scores a year by the mid-nineties. In some instances, of course, he found little jewelry. Most wealthy people in Dallas keep their best jewels in safe-deposit boxes at banks or in safes hidden away in their homes. In one burglary, however, when Mitch did find a small safe that he couldn’t open, he lugged it out of the bathroom window and then carried it as far as he could down the street and into some bushes before tiring, returning later that night with Jennifer to pick it up. Still, even when he did find a stash, his fence would pay him only a fraction of what the jewelry was worth, claiming he had his own exorbitant costs to have the jewels cut up to be resold. Mitch reportedly received $5,000 to $20,000 for a heist, a few of which brought in hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of gold and diamonds.

Yet Mitch didn’t seem to care about becoming rich. “He never spent a dime on himself,” said one of his half sisters. “He never bought clothes, and I think he had just one coat. At the apartment, the closet was full of Jennifer’s clothes, and I think Mitch had one drawer full of stuff, mostly T-shirts.” Jennifer did tell me that if Mitch suddenly showed up with a large wad of cash, he’d spend it mostly on her, taking her to get her nails and hair done, buying her new outfits, and then ending the day with dinner at Bennigan’s or, for a real treat, at the revolving restaurant inside the gigantic lighted ball at the top of Reunion Tower, which looms over downtown Dallas. Sometimes she’d wear some of the better pieces of jewelry that Mitch had acquired. Mitch was so in love with Jennifer that he once let her help him paint one of his Picasso imitations; when they were finished, he signed the painting “Dolan Shaw” and put it on a wall in their living room, right next to the bookshelf filled with a fish-shaped onyx sculpture that Jennifer’s mother had given them.

Mitch had plans to go legitimate someday—he did start a company called WebCanDo to create Web sites for small businesses—yet he never could shake the thrill of the heist. “I think he realized he had a gift for this kind of work,” a police detective told me. “He found a real joy in being able to do something few other people could do.” On Sunday afternoons, he and Jennifer would walk hand-in-hand through open houses for newly built mansions, in part to see how they were built and where the new homeowners would keep their jewelry. And inevitably, he began having Jennifer drive him past the Simmons mansion, with its off-duty DPS officer in the driveway and a trained German shepherd guard dog named Titus in the back yard.

No one in Dallas loved jewelry more than the glamorous Annette Simmons, the welder’s daughter from Tyler who met Harold in 1975 in a luxury box at a Dallas Cowboys game just as his fortune was starting to explode from his corporate investments and hostile takeovers. Annette adored fine jewelry the way Jennifer adored costume jewelry. She had jewelers from New York, Beverly Hills, and Dallas who called her regularly. She perused Christie’s and Sotheby’s catalogs for estate jewelry on the auction block. She was so well known for her interest in jewelry that husbands from Dallas’ mega-rich circles often asked her to buy jewelry for them to give to their wives.

Although Annette kept her most expensive jewels locked in safes and safe-deposit boxes away from the home, she still had a whopping two hundred pieces in four drawers in a closet of her large dressing room. “Some of those items meant the most to me,” she told me one afternoon, sitting in her living room, which is filled with the kind of French furniture tourists see at the Palace of Versailles. Her eyes reddened with tears. “There was a little diamond watch that my daddy gave me when I graduated from high school, the first piece of jewelry Harold ever gave me [a bracelet containing thirty small heart-shaped diamonds], and my first wedding rings from Harold [which she later replaced with bigger rings].” But there were also some monster rocks, including a forty-carat pink sapphire ring circled with diamonds that was worth at least $150,000—a jewel thief’s dream.

The January 1998 burglary, done while Harold and Annette were at their second home, in Santa Barbara, California, was Mitch’s masterpiece. He timed the entry to avoid the officer making one of his twice-hourly tours around the grounds and persuaded the dog not to bark (perhaps by feeding him cookies). Then he approached Annette’s dressing room window, cracked two panes with the sharp edge of his screwdriver, and removed the glass and part of the window frame so delicately that he didn’t trigger an alarm. He was in and out so quickly that Jennifer, who had driven over to a McDonald’s half a mile away to get a Diet Coke, had barely made it back to the pickup spot when he came flying out of the bushes with a pillowcase bulging with jewelry.

Although many wealthy victims of jewelry heists swallow their losses and ask the police to keep their names out of the newspapers, Annette was too distressed to do nothing. She hired an FBI agent turned private investigator, Michael Miles of Dallas, to make inquiries throughout Europe and Asia, send photos of Annette’s most valuable pieces to diamond merchants in Paris, Hong Kong, and New York City, and take out advertisements in jewelry magazines and the Dallas Morning News announcing a reward for information leading to the return of the jewelry. Meanwhile, the chairman of the Department of Public Safety, perhaps embarrassed that the robbery had happened on one of his men’s watch, okayed a team of DPS divers to search the pond behind the Simmonses’ house for jewels or any other evidence and assigned a DPS officer to assist with the Dallas Police Department’s investigation.

The lead investigator in the case, Joe Philpott, was a soft-spoken but relentless burglary detective who had been with the DPD for thirty years. Philpott ran all the usual traps: He had some of the employees at the house—from the housekeeper to the gardener to the gardener’s assistant—take polygraphs. He also took a look at two of Harold’s daughters from his previous marriages who despised him and Annette. A year and a half earlier, they had sued their father over the way he ran the family trust, in part claiming that he had used money that belonged to the daughters to buy Annette $1.6 million in jewelry. One of the daughters used to turn the photos of Annette toward the wall whenever she visited the home. Annette had found it curious that a photo of her and Harold on her vanity had obviously been picked up and moved during the burglary. Could it have been a calling card from the daughters? Or was the burglar so well informed about the Simmons family feud that he moved the photo to cast suspicion on the daughters?

As the weeks passed, Philpott found himself without a single decent lead. He tried to find out if a known jewel thief from Connecticut who was said to work on the East and West coasts had been making stopovers in Dallas. He checked into rumors that a legendary Dallas jewel thief from the sixties known as the King of Diamonds—a man who had never been identified but who had been bold enough to burglarize homes while the residents were throwing a dinner party—might have come out of retirement. Perhaps the most comical rumor that circulated through Dallas was that Annette herself had staged the robbery so that she could get insurance money to buy more jewels. (The Simmonses did receive $600,000 from the insurance company to cover their losses.)

Then, in the spring of 1998, Philpott got one of those nutty phone calls that detectives often get from citizens who claim to have inside information on cases. A man said he had seen the advertisement in the newspaper about a reward for missing jewels and he thought he knew who had them. The man told Philpott that a pretty girl named Jennifer had been coming to a couple of North Dallas apartment complexes known for drug dealing and was trading jewels for little bags of crack cocaine.

The man’s real name was Essie Evans, but he was known as Chickenman because he delivered orders for a small fast-food chicken restaurant near the apartment complexes. Over the years, he had gotten to know the drug dealers in the complexes, and sometimes when he’d make his chicken deliveries he’d tell customers that he could get them some nice crack for dessert. One evening, he saw a well-dressed young woman slowly driving by in a turquoise Tercel. She rolled down her window and told him she wanted to try some crack herself; soon a relationship was born. Once again, Jennifer was sneaking off from Mitch. “I don’t know what it was that made me do it,” Jennifer later told me during one of our conversations. “It started, I guess, a few months before the Simmons burglary, when a girlfriend of mine, who’s pretty wild, asked if I’d like to do some crack. I thought it would be fun to see what it was like, and then as time went on, I sort of, well, lost it.”

Mitch eventually found out where Jennifer was going, and whenever she disappeared, he’d drive through the parking lots of the apartment complexes, looking for the telltale Tercel. He’d knock on apartment doors asking if she was there. “Come home,” he’d say when he saw her. She always did, letting him put his arms around her as he took her away.

She’d tell him she was sorry, he’d forgive her, but then she’d keep returning to do drugs with Chickenman. He introduced her to different dealers, almost all of whom were women. (One of the most prominent dealers was a black woman named Blue; her chief rival was a black woman named Black.) A couple of days after the Simmons heist, before Mitch sold Annette’s jewelry to his fence for a paltry $25,000, Jennifer grabbed several pieces when Mitch wasn’t looking and hid them. Then, on subsequent visits to the apartment complexes, she’d pull the jewelry out of her Gucci purse and offer to make a trade.

Soon, throughout the apartment complexes, female crack dealers were wearing Annette Simmons’ rings, earrings, brooches, bracelets, and necklaces. “It was nice ice,” said Becky Reno, a dealer who took a necklace and four rings—two of which were matching ruby guards that she wore next to her wedding band—in return for a $40 bag of crack.

But in what would turn out to be a fateful decision for Mitch and Jennifer, Becky tired of the rings and pawned them at a nearby Cash America pawnshop, which offered them for sale for $29.58 each, advertising them as “ladies fashion rings.” Philpott checked pawnshop sales slips and hit pay dirt—a description that sounded like Annette’s rings. As is required by law, the sales slip listed the name of the purchaser, who turned out to be an employee of Mrs. Baird’s bread. Philpott got the rings and took them to Annette, who identified them as hers.

Realizing he would still need some leverage to get Jennifer to talk, Philpott told Chickenman that to get the reward, he’d have to agree to set up Jennifer. The next time she came to the apartment complexes to meet Chickenman and buy some crack, undercover police officers were waiting. They arrested Jennifer and took her to Philpott, who told her he could recommend to the district attorney’s office that the crack cocaine possession charges be dropped in return for her full cooperation in the police investigation. For nearly four hours she dodged Philpott’s questions. (Jennifer said she asked for an attorney: Philpott said all she asked for was her mother.) Finally, Jennifer broke down, told Philpott about Mitch, identified Mitch’s fence, talked about their previous burglaries, and then wrote out a confession about the details of the Simmons burglary.

The Simmonses’ property manager met Chickenman and gave him a reward of $25,000 along with a sweet thank-you note from the always-polite Annette, encouraging him to find Jesus and be saved. Chickenman had told Philpott he was going to use the money to go to drug treatment and buy a car so he could visit his mother in Mississippi. But he was so overcome with remorse about betraying Jennifer—she was such a nice girl, he kept telling Philpott—that he tracked her down one last time, gave her half of the reward money, and disappeared.

Meanwhile, in hopes of avoiding her own criminal charges, Jennifer had promised Philpott, who was still worried that he didn’t have enough evidence to convict Mitch, that she wouldn’t tell Mitch about her confession and that she would let Philpott know when and where Mitch would be doing his next burglary. Instead, Jennifer broke down and told Mitch at least part of the truth. She said the police had somehow found out about them and were trying to get her to talk.

For weeks, she and Mitch didn’t go out of their apartment except for quick trips to Jack in the Box. They peeked out of the window shades at the unmarked police cars in the parking lot. They became convinced that two young women who had just moved into a nearby apartment were not topless dancers as they had said but undercover cops who might try to seduce Mitch and get him to confess. Because Mitch believed that the satellite dish the two women had installed on their balcony was designed to pick up his conversations with Jennifer, he turned up the stereo whenever he and Jennifer talked.

Figuring he would get nothing more, Philpott obtained an arrest warrant for Jennifer and then one for Mitch. If he thought the arrests might get them to talk, he was mistaken. At the intake area of the jail, Mitch and Jennifer saw each other. Mitch suddenly broke away from sheriff’s deputies and ran to Jennifer, shouting, “I’m so sorry. I love you.” Just as he reached out to embrace her, the deputies dragged him away. “I love you too, Mitch,” Jennifer cried.

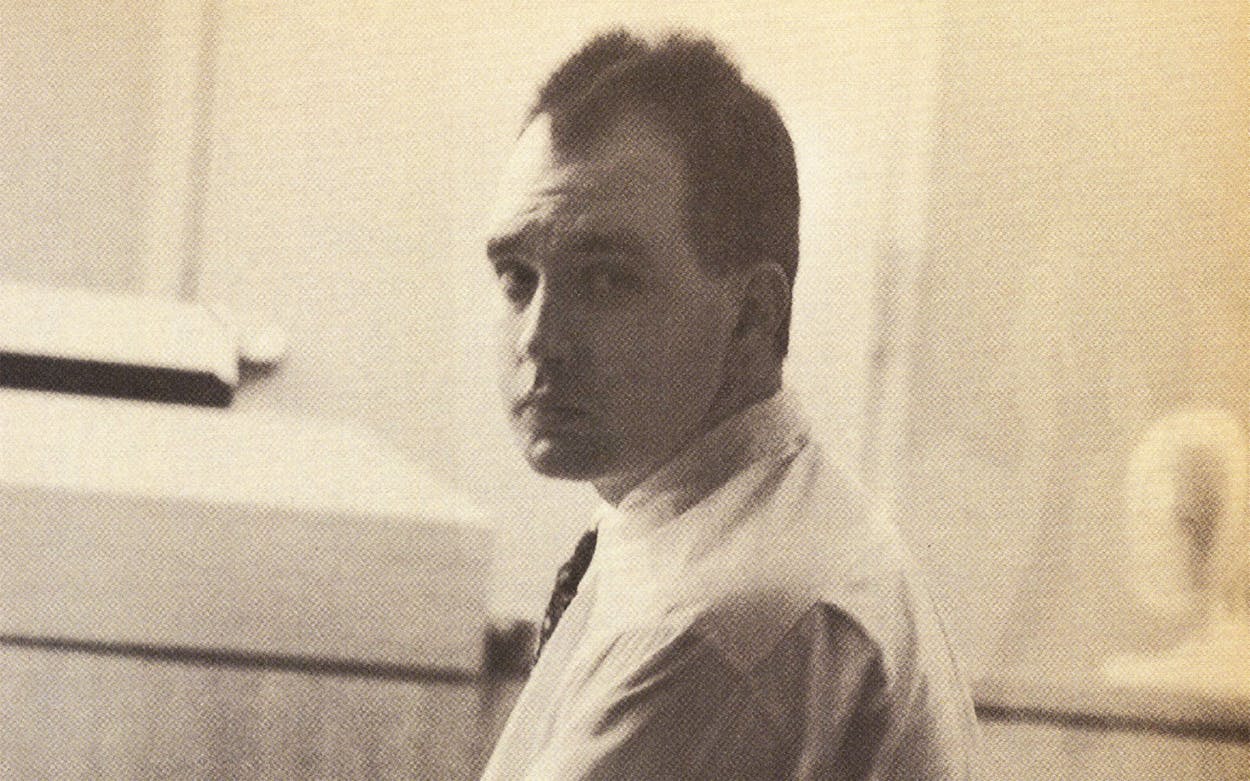

For most of the trial, which was held last summer, Mitch looked like he belonged behind a computer, sitting hunched forward in his chair, resting the side of his pale face against the palm of one hand. He was so devoid of expression that one attorney later said he seemed autistic. Because Dallas’ most successful jewel thief owned no dress shirt and no tie of his own, he had to borrow them from an attorney. In a holding tank outside the courtroom, Mitch complained to a bystander that his shirt was too tight. The man answered, “Hey, if you can squeeze through a window, then you can squeeze through a goddam shirt.”

Mitch’s lawyers were the legendary Dallas defense attorney Doug Mulder and his son Chris. The elder Mulder told the jury that Mitch couldn’t possibly be a jewel thief. He was so poor that his grandmother was paying his legal bills. (But Nancy Wiener later told me that she had never heard of Mulder and that she didn’t pay him a cent. The police speculate that Mitch’s legal fees were paid for by his fence in return for Mitch saying nothing about him.) Once testimony began, the Mulders had a field day mocking the drug dealers who arrived to talk about the jewels Jennifer sold them. The trial did seem to go badly for the prosecution. Jennifer refused to testify, citing her Fifth Amendment rights, and according to the police, the fence had conveniently disappeared for several weeks and could not be found in time to testify. But how could the Mulders get around the fact that Annette’s wedding guards had ended up at the pawnshop? In a hilarious last-gasp maneuver, the Mulders brought out a man who identified himself as a jeweler; he stared at the rings, blew on them, and pronounced, “They’re fake. You could get these at a Kmart.” The socialites who had come to the trial to support Annette gasped: Annette had been accused of wearing costume jewelry! The prosecution quickly called Bill Noble, the jeweler to Dallas’ moneyed class and one of Annette’s closest friends. He strutted into the courtroom in a beautiful Italian suit, performed a scientific acid test on the rings in front of the jury, and pronounced them authentic. Annette’s daughter, Amy, rushed out of the courtroom to tell her mother, who was anxiously sitting on a bench in the hallway. “They’re real,” Amy exclaimed. “They’re real!” The two women hugged.

The twelve jurors, mostly middle-class citizens who chuckled through much of the testimony, found Mitch guilty, but in the trial’s biggest surprise, they decided that he deserved only probation. The judge gave him a ten-year probated sentence, then ordered Mitch to pay $400,000 in restitution to the Simmonses as compensation for the stolen jewels that their insurance didn’t cover, which caused the socialites to gasp again. One of Annette’s close friends, Sandra Tucker, turned to me and said, “Oh, my God, this means he’s going to rob other people’s homes to get the money he owes Annette.”

In a later plea bargain, Jennifer pleaded guilty and also received ten years’ probation. She and Mitch were ordered by the judge not to contact each other during the length of their probation. Jennifer went to a drug rehabilitation program and then to a halfway house, and Mitch moved to a small apartment building owned by Jennifer’s mother that was behind a cheap Chinese restaurant near downtown Dallas. Some Mexican Americans who lived in the same building took pity on him and got him hired as a laborer at a construction site where they were working on a new home. The site happened to be in the Preston Hollow estates area that Mitch knew all too well.

But the story was hardly over. Late last fall Philpott arrived at Mitch’s apartment with a warrant for his arrest. The detective had been so disturbed over Mitch’s probated sentence that he had pulled out the files of every unsolved burglary in North Dallas in the previous five years—the period that would still be under the statute of limitations for burglary. He found a February 1997 case in far north Dallas where the burglar had cut himself as he came through a window and dripped blood through the house. When Philpott learned that an enterprising officer at the scene had collected blood samples, he ordered DNA tests. The DNA from that blood perfectly matched Mitch’s DNA. This case, as the cops like to say, was open and shut.

If no plea bargain is arranged, Mitch’s new burglary trial will begin later in the year. (Chris Mulder is again defending him.) It is unlikely that Mitch and Jennifer will be arrested for their other burglaries. Some are protected by the five-year statute of limitations and others cannot be prosecuted because of a lack of evidence—no jewels have been found, and it’s likely that neither Mitch nor Jennifer will testify. Jennifer’s oral statements are not enough to produce a conviction, and her only written confession was limited to the Simmons case. Nevertheless, Philpott remains obsessed with Mitch’s earlier burglaries, and he still suspects some of the jewelry was hidden in Dallas. He got a court order to dig up the yard of one of Mitch’s great-aunts, where he thought some jewelry might be, causing a minor scandal in her neighborhood. There is also the question of whether Mitch had received any inside information about where to look for the jewels once he got inside these large mansions. By all accounts, he did have an uncanny knack for finding the loot. Was it possible that someone who was part of Dallas society, someone who went to lunches or parties at these homes, had passed on to someone else, who then passed the information on to Mitch, details about where the jewelry might be?

Mitch isn’t talking about any details of the crimes. He still insists to his friends and family that he is an innocent victim of a vengeful Harold and Annette Simmons, who are trying to use their muscle around town to keep him behind bars. In one letter to his grandmother, he wrote that the police were “using the other inmates to harass me, intimidate me, question me about my personal life and case. In one case they were trying to use an extremely well-built black man, to threaten me with bodily harm and un-natural sex . . .” At least in his letters to his grandmother, he seems desperate and even terrified. “I have suffered a nervous breakdown for 3 days in a row now because of this matter,” he wrote in one letter. It’s as if the daring persona he put on as a cat burglar is now shattered, and he is once again the quiet, unassuming computer nerd who wants to spend his evenings designing Web sites. In fact, Mitch recently made a collect call from jail to a friend to remind him what still needed to be changed on a Web site that Mitch had created for him. Then, after a pause, Mitch asked if his own computer was in a safe place.

As for Jennifer, she should be out of her halfway house shortly and on to a new life—one that she says will be free of drugs and crime. She started writing poetry (“I’m no longer a fallen angel/I can spread my wings and fly”). And she got a job at a sandwich shop. After a few weeks she was asked to be an assistant manager. It seemed that all the other employees kept getting fired for stealing.

When I met her for the last time, just before Christmas, she was wearing a batch of costume jewelry. On each of her fingers (except for her thumbs) were little silver rings, one shaped like a butterfly, another like a frog. She wore large hoop earrings and a gold bracelet adorned with fake diamonds. “Nothing cost me more than ten dollars,” she said proudly.

I asked her how it was going to feel living without Mitch. “It’s best for both of us if it happens,” she said, but her face was pensive. “You know, I’ll always look back on those days and think, ‘How in the world did we do all that? How did we pull it off?’ ” She told me that she had heard Mitch had sent a letter to a mutual friend in which he wrote, “Tell Jennifer we were always a team, and they can’t take that away from us.”

For a moment, I thought she was going to cry. “Oh, well,” she said, “we were a team, that’s for sure.” Her Adam’s apple bobbed up and down. Then she took another sip of Diet Coke, her straw making a snerkling sound as she fished for the last drops among the ice at the bottom of the glass.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Crime

- Dallas