This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The publisher of a Juárez newspaper answered a knock at his door one evening and found two strangers standing on his doorstep. “We have come here on behalf of a friend,” one of them said in Spanish. “He would like to pay you a substantial sum of money every month, and in exchange, you will let him review every article you intend to publish about Amado Carrillo Fuentes.”

The publisher tried to conceal his fear. “No,” he said. “I can’t agree to that sort of thing.”

The two strangers looked at each other. One of them said, “Well, then, since you can’t do that, let’s try another arrangement. Either you will let our friend pay you a substantial sum of money every month in exchange for which you will not publish anything about Amado Carrillo Fuentes, or you will be killed.”

The men on the doorstep then said, “Buenas noches,” and departed into the Juárez night, leaving the publisher to ponder the two options. Overnight, a third choice occurred to him. He resolved to sell his newspaper.

This story about the notorious Mexican drug trafficker Amado Carrillo Fuentes was told to me by a knowledgeable American source. When I told it to two members of the Juárez media one morning in October, they exchanged knowing looks. Earlier in the year, said one of them, a photographer from the publisher’s paper had taken pictures of Carrillo’s compound near the Juárez racetrack. An interested party later contacted the paper. His message was succinct: “Pesos or bullets?” The photographs never made it into print.

“Here in Juárez,” the other added, “no one mentions his name in the press. Television, radio, newspapers—it’s the same editorial policy.”

The three of us were having this conversation over coffee at Sanborn’s, a fashionable restaurant on the Paseo Triunfo de la República frequented by politicians, journalists, and industrialists. Three months before, it was widely rumored that Amado Carrillo Fuentes had made an appearance in this very restaurant, accompanied by several bodyguards, a few members of the heroin-smuggling Herrera family, and a man who happened to be a Mexican police official. Though it was a rare sighting of the elusive drug lord, there could be no doubt that Carrillo intended to be seen. “It was a demonstration of his strength to dine in public with the official” one of the members of the Juárez media told me. “He was reminding everyone who was really in charge of the Juárez plaza.”

Reminders of Carrillo’s power have usually come in other forms, ranging in degrees of subtlety—from the Boeing 727’s bearing tons of Colombian cocaine that land on his rural Chihuahuan airstrips in the dead of night, to the bodies strewn across the southern outskirts of Juárez every time Carrillo’s drugs fail to reach their destination. Both with pesos and with bullets, the so-called Lord of the Skies has emerged as the most dominant drug trafficker in Mexico. More cocaine enters the U.S. through his organization than any other, in addition to the substantial quantities of methamphetamine and black tar heroin his underlings ferry across the border. By no coincidence, today more drugs are smuggled through the El Paso–Juárez corridor—consisting of four pedestrian and vehicular bridges linking Mexico to Texas and the U.S.—than anywhere else in America. Thanks to Amado Carrillo Fuentes, El Paso is well on its way to becoming a Little Miami, a city whose prosperity is dependent upon the drug trade. And, thanks to Carrillo, Juárez has become a city held hostage, where two hundred to four hundred people have been murdered over the past three years as a result of the drug trade.

None of this has occurred by accident. In his ascendancy, the fortyish Lord of the Skies benefited from luck and opportunity, apprenticeships and family relations, the misfortunes of his peers and the good sense to learn from their mistakes. As a result, Carrillo is untouchable, his incalculable wealth and his equally innumerable crimes scarcely blinked at by the Mexican government and its law enforcement officials—while on the other side of the border, just a couple of miles from the warehouses that store his drugs, American federal agents gnash their teeth and wait for Carrillo to commit some fatal error. It is like waiting for a bridge to collapse.

The history of El Paso–Juárez as the drug smuggler’s preferred port of entry begins around 1983, when a Colombian operative showed up in Juárez and established residence there. By the time the man departed in 1985, he had built an elaborate network by which the infamous Medellín drug cartel could fly its Colombian cocaine into the interior of Mexico and have the drugs driven north into the United States by Mexican traffickers, who would then deliver the goods at a designated site to Colombian distributors, who would disperse the cocaine throughout the biggest cities in America.

American law enforcement officials knew nothing about the Colombian operative or his operation until some time after September 28, 1989. On that day, the Drug Enforcement Administration received a tip that led agents to a warehouse in Sylmar, California, a suburb of Los Angeles. After obtaining a warrant, DEA agents entered the warehouse. What they discovered was more than $12 million in cash stuffed in boxes and bags on the floor of the warehouse, along with a staggering quantity of boxed cocaine: 21.38 tons, with a street value of $6.5 billion. It was, and still is, the largest cocaine seizure in American history.

Four men were initially spotted around the warehouse. They were arrested and then interrogated at the DEA headquarters in Los Angeles. The suspects were surprisingly forthcoming—until a Colombian American woman burst into the interrogation room and declared, “I represent all four of these men and wish to speak with them privately.” After the attorney left the building, the four suspects told DEA agents that they had nothing further to say. But by then, a key fact had already been divulged: all 21.38 tons had entered the U.S. through the El Paso–Juárez corridor.

“The Sylmar bust was our wake-up call,” says Phil Jordan, who at the time was the DEA’s special agent in command of the Dallas district and now is the director of the El Paso Intelligence Center, which gathers and analyzes all law enforcement data pertaining to international drug trafficking. Until that point, the feds had almost no clue that the Colombians had set their sights on Juárez. Traditionally, drugs had moved into the U.S. via New York City, until crackdowns in the sixties and seventies inspired the drug lords to ship their products through Caribbean waters and into Miami. The federal government responded in 1982 with the South Florida Task Force and stepped up interdiction along the Florida coastline. Multi-ton seizures compelled politicians to proclaim that America was winning the War on Drugs. Yet federal agents knew otherwise. Inland seizures proved that massive quantities of marijuana, cocaine, and heroin were still finding a way to cross the border. But where was the corridor?

Common sense would have given them the answer: Mexico. After all, Mexicans had mastered the art of smuggling contraband into the U.S., from guns to tequila, over the course of the past two centuries. The savvy, the manpower, and some of the tools of the trade—including police corruption—were already in place for the Colombians to exploit. Furthermore, a cargo traveling across Mexico wouldn’t have to sit in the water until conditions were favorable along the coastline. The drugs could be flown into the Mexican interior, far afield of U.S. radar detectors, and then driven to the edge of the border. The drugs could sit there, indefinitely warehoused, until the time was right to join the procession of vehicles that crossed the international bridges.

And which bridges? Federal anti-drug agencies guessed the Tijuana ports of entry. But despite the heavy trafficking from Baja California into the U.S., clogging up the Tijuana corridor wasn’t going to arrest the influx of illegal drugs by any means. For as any geography textbook would have told them, the most heavily populated metropolitan area on any international border in the entire world is El Paso–Juárez. And as any map would have shown them, a vehicle that crosses the Bridge of the Americas into El Paso is, in a matter of minutes, on Interstate 10—bound westward for California, eastward for Florida, and within an hour’s drive of 1-25 north. An architect in the employ of traffickers could not have designed two more accommodating sister cities. A tractor-trailer could receive five tons of cocaine at a Chihuahuan airstrip, drive anonymously through the cramped international checkpoint, and then become instantly lost in the El Paso traffic before disappearing altogether. During 1988 and 1989, the Sylmar conspirators had succeeded in smuggling more than two hundred tons of cocaine through this conduit.

Following the September 1989 seizure at the Sylmar warehouse, federal agents moved with the haste of the monumentally chastened. Through seized smuggling ledgers and plea-bargain arrangements with some of the conspirators, they learned that members of the Medellín cartel were working with a Juárez trafficker named Rafael Muñoz Talavera. The Colombians transported their cocaine to a ranch airstrip in Villa Ahumada; from there Muñoz’s drivers moved the product seventy miles up the road into Juárez and across the international border in the trunks of old model LTDs and Oldsmobile Cutlass Sierras. Every Monday through Friday for two years, four or five of Muñoz’s smuggling vehicles crossed into El Paso nightly, each carrying 150 to 170 kilograms of cocaine in the trunk; not a single one was searched at the bridge. The drugs were repackaged and warehoused in El Paso until Saturday afternoons, when the cocaine was reloaded into hidden compartments of Peterbilt tractor-trailers and the trailers filled with hundreds of breakable Mexican artifacts. The drivers set out for Ruidoso, New Mexico, bearing bills of lading for a dummy corporation called Ruidoso Arts and Crafts and receiving information along the way from conspirators about Border Patrol activity along U.S. 70. From Ruidoso, new bills of lading were inked indicating that the truck was ferrying contents from that city rather than El Paso. Then, assisted by road surveillance teams, the trucks drove on the back roads of New Mexico into Arizona, where they rejoined Interstate 10 and headed for the Colombian distributors who would meet them at the Sylmar warehouse.

The scheme was at the same time extravagant and maddeningly simple, but after the seizure at Sylmar, the conspiracy was dismantled. Between 1990 and 1993 almost all of the Mexican organizers, including the Juárez patrón Talavera, were brought to justice. But the corridor still beckoned. The conditions that made El Paso–Juárez so appealing to the Colombians in 1983 have only intensified. In 1994 more than 16 million vehicles crossed the three bridges linking Juárez to the United States. Less than 10 percent of those vehicles are submitted to a detailed inspection by U.S. Customs and Immigration agents at the border checkpoint. As George McNenney, the special agent in charge of the U.S. Customs Service office in El Paso, observes, “It’s not so much a matter of resources as a matter of other realities. Yes, we’re a law enforcement agency. But we’re also an agency that facilitates trade. If we checked every vehicle, there would be lines all the way to Mexico City.”

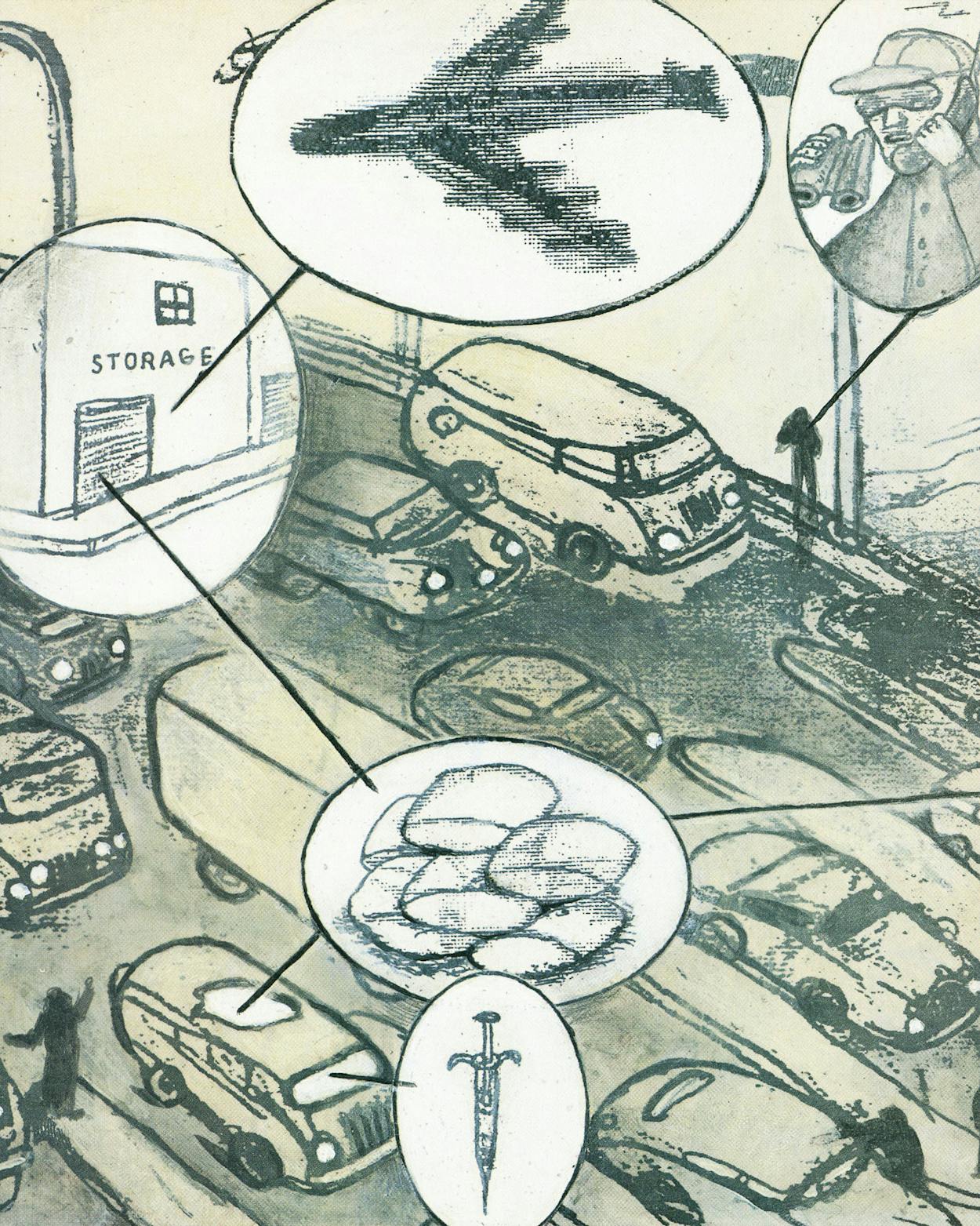

That more than 90 percent of the vehicles enter the U.S. from Juárez unsearched instantly guarantees, as one senior federal agent puts it, “odds that are far greater than Las Vegas odds.“ To increase the odds in his favor, the agent adds, a trafficker “could send several cars across the bridge and assume that one of them will be seized, just to help discern the pattern of detection.” (The drivers oftentimes are ignorant Juárez peasants paid a nominal sum to drive the vehicles across the border to an El Paso safe house, no questions asked.) The traffickers improve the odds further by creating hidden compartments such as detachable dashboards that harbor the drugs within the vehicle. Then there are the spotters—individuals paid by traffickers to loiter around the checkpoint and monitor the border inspectors. One afternoon while standing by the Bridge of the Americas station, I asked a Customs inspector if there were any spotters in the vicinity. Hesitating only for the moment that it took for him to snicker darkly, the inspector pointed out four likely suspects: two leaning against the pay telephones twenty yards away, another hunched in the shade near the employee parking lot, and a fourth positioned near the center of the bridge, some fifty yards distant. The latter was an elderly man in rumpled clothes and a straw hat. I could just make out the cellular phone in his hand. The vehicles idling in the traffic pattern between Mexico and the U.S. would receive a coded message on their digital pagers from the spotters—333, for example, meaning that the driver should make haste for lane three, or 000, indicating that the Customs agents with drug-sniffing dogs were checking the driver’s lane and that a hasty return to Juárez would be in order.

Yet the crude ingenuity of spotters and custom-designed drug vehicles could be dispensed with. At the El Paso–Juárez corridor, the deck is hopelessly stacked in the smuggler’s favor. At issue is not the viability of the conduit, but rather which trafficker will become its master—and thus the primary link between Colombian drugs and their American consumer. After the Sylmar bust in 1989, the link was severed, but not for long. Someone would step forward. Someone would take charge of the Juárez plaza.

“To tell you the truth, we’re just not getting much intelligence about him because no one is talking,” a veteran federal agent said to me on the subject of Amado Carrillo Fuentes. “His circle is small, and he doesn’t come out of it. And everyone else is afraid to tell us anything.”

American anti-drug agencies know embarrassingly little about their biggest nemesis. Intelligence reports list three different dates of birth for Carrillo, placing him between 40 and 45 years of age. He is either a third-grade dropout or a law school graduate. He has two children by a wife of unknown name and origin, and he is said to have a girlfriend in Ojinaga and another in Sonora, each with a child that is his. The three existing photographs of Carrillo are dated but suggest a tall, unremarkable-looking man with hazel eyes, soft cheeks, sullen lips, and a youthful head of dark hair. Though rumor has it that he alters his appearance with colored contact lenses and hair dye, most federal agents are doubtful. He is his own disguise, conveniently nondescript.

Even his exact birthplace is a matter of dispute, though everyone agrees that Carrillo was born in one of the agricultural villages outside of Culiacán, the capital of the Pacific coastal state of Sinaloa. Like Sicily in Italy and Medellín in Colombia, Sinaloa is a hothouse of mobsters, a violent and provincial region surrounded by marijuana plantations and opium fields. In the mid-sixties, when Pedro Aviles Pérez—the acknowledged godfather of the Mexican drug trafficking federation—rose out of Sinaloa to claim smuggling supremacy, “you could hear gunfire in Culiacán every night,” recalls a senior U.S. official.

Carrillo didn’t have to seek out strangers to learn about the drug trade. His uncle Ernesto Fonseca Carrillo was one of the country’s biggest traffickers. Fonseca had the dim, addled visage of a born thug—“To look at him,” says one agent, “you wouldn’t hire him to sweep your sidewalks.” Yet Fonseca was also Aviles’ bookkeeper, and he maintained ties to Colombian suppliers following Aviles’ assassination by Mexican federal judicial police in 1978.

Carrillo started at the bottom, loading and driving marijuana to safe houses. Eventually, and most likely through his uncle, he made his acquaintance with the Herrera family, Mexico’s notorious heroin-smuggling family from Sinaloa’s neighboring state, Durango. The Herreras were the last of a breed in Mexico, an exclusively family-run operation that controlled every single aspect of their trade, from planting marijuana and poppy seeds in the foothills of Las Herreras to distributing the product in Chicago. The godfather, Jaime Herrera Nevares, was a functionally illiterate ex-cop with a nonetheless dignified Old World bearing. He despised the rude and arrogant Colombian drug lords and refused to sell their cocaine. Carrillo helped tend the Herrera opium fields, and it is likely that he fell into the company of Jaime Junior, the godfather’s son, who was about Carrillo’s age and who epitomized a new style of trafficker: the Concorde-flying, thousand-dollar-boot-wearing, gold-and-diamond-ornamented internationalist.

“During Jaime Junior’s era, we began to see something we hadn’t seen before,” says Travis Kuykendall, a former head of DEA operations in El Paso and now an administrator of the West Texas High Intensity Drug Trafficking area, an organization that disperses federal funds to anti-drug agencies. “Traffickers began to show their money on the American side. They bought big mansions, invested in racehorses and feedlots, and partied in Las Vegas. They believed they were invulnerable.” Prominent among this ilk was Rafael Caro Quintero, a brutal Sinaloan who owned a magnificent estate in San Diego, California, as well as a pet lion. In the early eighties Caro Quintero recruited thousands of Sinaloans to tend to his marijuana plantations near the Chihuahuan town of Ciudad Jiménez and the nearby village of Colonia Búfalo. Amado Carrillo Fuentes showed up in Chihuahua about this time. In this northern border state, Carrillo received a crucial apprenticeship under the most flamboyant trafficker in modern times: Pablo Acosta Villarreal, the patrón of the Presidio-Ojinaga plaza.

Acosta was the bridge that connected the old drug lords with the new. His grandfather was a bootlegger who switched over to smuggling marijuana after Prohibition. Acosta started out smuggling pot in mule carts and melon trucks; by the mid-eighties, he was using twin-engine planes to ferry grass, heroin, and cocaine across the border. “He set the standard for moving multi-ton quantities—and for flaunting it,” says one federal agent.

Carrillo moved to a house on a hill north of downtown Ojinaga and became Acosta’s lieutenant. They rode together on drug-running expeditions and freebased cocaine together. Carrillo curried favor with his boss by buying him gold wristwatches and necklaces. In turn, he learned the intricacies of staging and moving major loads into Texas: how to set up a transportation network, how to time a delivery, whom to bribe, and whom to trust. Just as valuably, he learned from Pablo Acosta’s excesses. For all of his generosity toward the Ojinaga peasants, Acosta was recklessly trigger-happy, given to ambushing rivals and being ambushed himself. That he freebased incessantly made his conduct that much more erratic. By 1987 Acosta had so undermined his own authority that Mexican law enforcement officials felt sufficiently emboldened to take him down. In April they surrounded his ranch in Santa Elena, just across the Rio Grande from Big Bend National Park. After a ninety-minute shoot-out, Pablo Acosta lay dead.

By that time, Carrillo was long gone. He had fled to Torreón in Durango, where he resumed his partnership with the Herreras. In 1988 he relocated westward to Hermosillo in Sonora, the state just north of Sinaloa and bordering Arizona, where his brother Cipriano had set up shop. It was an unsettling time for Mexican traffickers. Following the torture and murder of DEA agent Kiki Camarena in 1985, Mexican authorities had arrested two men allegedly responsible, Rafael Caro Quintero and Ernesto Fonseca Carrillo, Amado’s uncle. A mass arrest of more than a hundred American-based Herrera affiliates had decimated that organization. The warring federation’s most able peacemaker, Juan Esparragoza Moreno, had been jailed, and by 1989 the most powerful Mexican kingpin, Miguel Félix Gallardo, had been arrested in Guadalajara and charged with conspiring to murder Camarena. That year as well, Mexican authorities announced that they had discovered the body of Cipriano. The official ruling was suicide—but a senior U.S. official told me, “Yeah. He put an AK-47 in his mouth and shot himself fifteen times.”

When the smoke lifted, the Mexican drug federation was in tatters. A gaping power vacuum spanned practically all of western Mexico. Cipriano wasn’t there to control Sonora. Acosta had fallen in Ojinaga. And in the burgeoning Juárez plaza, two drug lords—Gilberto “El Greñas” (“the Mophead”) Ontivero Lucero and former Mexican Federal Security Police regional director Rafael Aguilar Guajardo—had been hauled into custody in 1986. Following the dismantling of Rafael Muñoz Talavera’s Sylmar operation in 1989, the plaza was there for the taking.

He arrived in Juárez with impeccable credentials: nephew of Aviles’ bookkeeper, brother of Sonora’s drug lord, Acosta’s right-hand man, a smooth veteran of the trade who had worked his way up from the fields of Durango and Chihuahua and acquired his share of Colombian contacts along the way. He was handy with an automatic, but he preferred alliance building to Acosta-style gunslinging. The dirty work he left to the underlings of his brother Vicente, who accompanied Carrillo to Juárez but kept an even lower profile.

In the vein of his predecessors Aviles, Gallardo, and Esparragoza, Carrillo united the drug lords of Mexico and convinced them that if they let him broker the major deals with the Calí cartel in Colombia, everyone would benefit. He established ties with the traffickers who served as gatekeepers of the twelve Mexican ports of entry, from Tijuana and Mexicali, along the California coast, to the three Arizona corridors and Matamoros, on the western lip of the Gulf. His cross-country smuggling operations served dual purposes: to maintain his alliances and to avoid detection by the U.S. intelligence agents stationed in Mexico. Along the way, he bankrolled industrialists and bought off Mexican law enforcement officials—almost always in private, except in Juárez, where periodic public appearances were necessary to preserve his status in the plaza.

The nature of his deals with the Colombians varied according to the vagaries of the market and the conditions in the corridors. Having received several barrels of Peruvian coca paste and processed it into white powder in their labs, the Calí traffickers would establish where demand in the U.S. was highest. Then the cartel honcho, Miguel Rodriguez Orejuela, would call his close friend Carrillo. Taking into account the size of the load, Carrillo would consult with the Mexican drug federation’s division heads to determine the optimal means of delivery into Mexico. Sometimes the cocaine would be ferried through the Pacific and transferred onto fishing boats and pleasure crafts controlled by Carrillo. More often than not, however, the drugs would arrive by air. The planes would fly with their lights off and land on an obscure airstrip somewhere in the rural interior. A fuel truck would be waiting, along with half a dozen or so other trucks. The truck drivers would load the cocaine into their vehicles, the plane would be refueled, and then the airstrip would be deserted. The cargo trucks would be driven to warehouses along the border—usually in Juárez—where the drugs would be repackaged and stored.

When the time was right, the gatekeeper—in Juárez’s case, Vicente Carrillo Fuentes—would select the best method for getting the product across the border, as well as the pasadores (border crossers) to do the honors. Some shipments might be flown across, though American radar balloons and Air Force pursuit planes have proved an effective deterrent to this approach. Or the goods might reach the U.S. via tunnels—like the one federal agents discovered this past summer in Nogales, which originated in the floor of an abandoned downtown church, hooked up to the city’s sewer system, and passed directly underneath the checkpoint into Arizona. (Though tunneling into Juárez would require the difficult measure of digging underneath the Rio Grande, one federal analyst cautions, “Amado’s imagination is the key. If you try to pin him down with the overland method, he’ll kill you with a tunnel.”) But the pasadores would in all likelihood cross in vehicles—though the type (cargo trucks, vans, Ford Tauruses) and the timing of the crossing would be matters of deliberation. Once in America, the drugs might be stashed in safe houses throughout El Paso, repackaged once more, and moved by different vehicles out of Texas; or the pasadores might simply take the border access ramp to the freeway and slip into the flurry of interstate traffic.

Compromising law enforcement officials on either side of the checkpoint would surely enter into the equation, though to what extent is difficult to gauge. Carrillo’s pesos-or-bullets offer would be tendered throughout Juárez, where, as one veteran federal agent in El Paso puts it, “all the officers, both federal and local, are either afraid of Carrillo or compromised.” On the American side, U.S. Customs officials frequently order random and spontaneous searches of border traffic with drug-sniffing dogs to keep both traffickers and corrupt inspectors off-balance. Still, as one senior American law enforcement official in the area observes, “The sheer numbers of vehicles coming across the border explain the success of drug dealers more than corruption would. Yes, corruption may be there. But how much is even needed?”

Throughout Mexico, and even in Juárez, other enterprising traffickers continued to ply their trade. But what distinguished Carrillo’s organization from the rest was size. The Colombians wanted huge volumes moved and moved in a hurry. Carrillo was fortunate to be firmly in control of the Mexican drug federation and thus a major beneficiary when the Calí cartel began purchasing massive Boeing 727’s and French Caravelles to replace their twin-engine planes. Bigger planes meant bigger deals—assuming, of course, that the patrón could provide larger airstrips, more smuggling vehicles, and greater numbers of pasadores. Carrillo could provide. Unlike the Herrera family-run organization, he contracted the services of numerous outsiders. This meant that he could handle shipments both vast and small, keeping costs down by not maintaining a bloated payroll and, at the same time, keeping various factions happy—and, not coincidentally, making his operation’s activities less traceable. Though he had cultivated a strong relationship with cartel principal Miguel Orejuela, Carrillo’s business did not seem to suffer in the least when Orejuela was arrested by five hundred Colombian policemen and soldiers in Calí this past August. The 727’s continued to land on his airstrips. His value to the Colombians meant that the Lord of the Skies enjoyed sweetheart deals. Frequently they would pay him 50 percent in cash and 50 percent in product—a huge boost in profit because Carrillo’s people could cut the pure cocaine and, in doing so, double or triple the dividend.

The Colombians regarded Carrillo as one of their own. He went about his business with cool, impersonal precision. He wasn’t an egotistical hothead like Juan García Abrego, the Matamoros patrón who seemed to enjoy the notoriety of being the only international trafficker ever to wind up on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted Fugitives list. Carrillo didn’t go ordering the deaths of government officials as Abrego was suspected of doing, or spraying bullets at his rivals as the Joaquín “El Rápido” Guzmán and Arrellano Félix factions had been doing to each other for years. As a result of their brashness, Abrego and the Arrellano Félix brothers were on the lam (the latter for allegedly murdering a Roman Catholic cardinal by mistake while trying to assassinate Guzmán in 1993), and Guzmán was behind bars. Unlike the other patrones, Carrillo never partied in America, where drug-trafficking indictments awaited him and justice was not so easily compromised. The Lord of the Skies remained standing because he didn’t shoot himself in the foot.

Yet Carrillo was not untouchable in the Colombians’ eyes. Like anyone else, he would be held accountable for the errors of his organization. In August 1993 more than nine tons of cocaine—believed to have been sent from Calí chief Orejuela to Carrillo’s organization—were seized off the coast of Mazatlán by the Mexican navy. The seizure, likely made possible by an informant among Carrillo’s ranks, amounted to a $20 million loss for the Colombians. Not long after that, Carrillo, his wife, their two children, and a few friends were dining at Bali Hai, a restaurant in a suburb south of Mexico City, when several hitmen walked in and opened fire with their automatic weapons. In the shower of bullets, two of Carrillo’s dining companions were killed.

If, as was speculated, the assassination attempt was ordered by the Calí cartel as payback for their loss at Mazatlán, the Lord of the Skies and the Colombians apparently managed to patch things up in a hurry. Perhaps it was the cartel’s basic admiration for Carrillo that made appeasement possible. After all, the hitmen apparently hadn’t seen enough photographs of the camera-shy Carrillo to know whom to take aim at. As a result, they went after the two dining companions who had tried to flee; in the meantime, Carrillo simply ducked under the table. His stealth, once again, had carried the day.

In January of this year DEA and Customs officials took aim at one ring of Carrillo’s Juárez pasadores: the port runners. Throughout 1994 this particular smuggling ring had employed a crude but surprisingly effective means of transporting cocaine across the border. They simply drove their cars up to the checkpoint and, if motioned over to a secondary-search lane by an inspector, stomped on the accelerator and barreled across into El Paso. More than 250 port runners had successfully sped their way into the U.S. in 1994, ferrying an estimated ten tons of cocaine. Acting in conjunction with the El Paso Police Department, the Department of Public Safety, the Immigration and Naturalization Service, and the Internal Revenue Service, DEA and Customs agents infiltrated the port-running operation and on January 30 arrested eighteen members of the organization, seizing 7,034 pounds of cocaine and 2,559 pounds of marijuana.

One of the men in charge of the interagency roundup, Travis Kuykendall (then with the DEA), was both pleased and worried. “We took down too much coke for there not to be repercussions in Juárez,” he now says.

Four months later, Chuy Márquez, a port runner who had managed to avoid arrest, was sitting with his girlfriend in his car outside the Juárez fairgrounds when the two were met by a hail of bullets. At least Márquez’s body would be accounted for. “Everyone above him in the operation has just disappeared,” says Kuykendall. “We have pretty good information that they were all assassinated.”

It has become a matter of grim predictability in Juárez: Whenever a major seizure of Carrillo’s drugs takes place on the American side, there is hell to pay. “He immediately orders the assassination of everyone who could have turned the shipment in,” says Kuykendall, “and bodies fall left and right.”

More often than not, they fall in familiar fashion: hands cuffed or tied behind the back and a single bullet to the back of the head. A few of the bodies have been found in the city garbage dump. Others have been strewn about in Lote Bravo, just south of Juárez. A few hits have taken place farther afield, as in the case of Rafael Aguilar Guajardo, a rival Juárez drug lord who was believed to have cooperated with U.S. agents on the Sylmar case. For his sins, Aguilar was shot to death while vacationing at the Hyatt Cancun Caribe in April 1993. Back home in Juárez, seven of Aguilar’s associates were also executed.

Some of the bodies found in the past year were informants on the DEA or FBI payroll, but most of the rest were individuals killed without any evidence that they had given law enforcement authorities any information of any kind. In the court of Amado Carrillo Fuentes, to be suspected—or to be close to someone suspected—is to become immediately eligible for the death penalty, according to U.S. intelligence officials. In November 1994, in the trunk of a Honda Accord abandoned on the Bridge of the Americas, El Paso police officials found the bodies of retired Mexican police official José Muñoz Rubalcava and his two sons. The word on the streets of Juárez was that the ex-cop was a DEA informant, and as if to punctuate this suspicion, his mouth was bound with a yellow cord and bow—gift wrapped, as it were.

The Juárez authorities argued that the bodies were found on the American side of the bridge, and that the matter was therefore outside of their jurisdiction. Not that the location of the corpses makes much difference: In the two hundred to four hundred drug-related homicides in Juárez over the past three years, no one can point to a single arrest that has been made. The Juárez government’s failure to prosecute Carrillo in connection with the killings corresponds with its failure to curtail his trafficking in any recognizable way. Those failures, in turn, reflect a failure that is national in scope. Despite Mexico president Ernesto Zedillo’s declaration at the White House on October 10 that “we are determined to use every resource at our disposal to fight tirelessly against the evil of illegal drugs,” the only warrant possibly outstanding for the Lord of the Skies in Mexico is a weapons charge—“the equivalent of jaywalking,” as one federal analyst dryly notes.

“They’re not looking for Carrillo, they’re not investigating Carrillo,” says Kuykendall. “We are, but they’re not. It’s a shame that the citizens of Juárez are under siege by his group and nothing is being done.” Indeed, the shared silence among the Mexican media, law enforcement authorities, and government officials hasn’t fooled the Juárez public. They know all too well that since Amado Carrillo Fuentes took charge of the plaza, their city has become a far more dangerous place. And though their outrage has compelled them recently to elect a new mayor who pledges to fight drug trafficking, they have heard the rumors that high-ranking federal police officials break bread with a billionaire smuggler, and they are under no illusions as to who runs their plaza.

There is a peculiar irony in all of this for the city that stands a stone’s throw away from the carnage. Despite the tons of cocaine, marijuana, methamphetamine, and heroin that surge through Juárez and across the Rio Grande, El Paso seems at ease. Its homicide rate is low, its legal system appears far less tainted by corruption than the drug corridors along the Rio Grande Valley, and its streets seem no more or less blighted by drug abuse than any other city with more than half a million residents. Instead, drugs have lent El Paso a kind of false prosperity. The city enjoys a monthly cash surplus ranging from $50 million to $70 million—meaning that upwards of half a billion dollars annually circulates through El Paso without actually being generated by its economy. Though local officials protest that the surplus comes from tourist dollars, federal officials point to the tens of millions in currency actually seized in El Paso from drug transactions as a more likely indicator. In any event, the correlation between the El Paso–Juárez corridor’s premier trafficking status and the ranking of El Paso’s cash surplus as fifth highest in the nation is difficult to dispute. The hot money has helped buoy the local real estate market and has boosted car and liquor sales; it is providing El Paso with an economic stimulus that the city has neither earned nor can count upon.

“One day we’re going to wake up and realize that much of the economy of El Paso is reliant on drug money,” says Tom Kennedy, an assistant special agent in charge of the DEA’s El Paso office. “If we’re ever successful at putting away Carrillo and shutting down the drug traffic here, numerous businesses in this city will crash and burn. El Paso is not a big city like Miami; it won’t be able to absorb the impact. It’ll be like a cancer—something we can’t feel and can’t diagnose until we experience that sudden pain. And then it will be too late.”

Perhaps we owe a debt of gratitude to Amado Carrillo Fuentes for the clarity he has lent to the never-ending debate over American drug use. For while the Lord of the Skies reigns unfettered, one need not even attempt to calculate what his drugs are doing to our streets or our children. We can instead stick to the inarguable: In Juárez, the killing is done with bullets; across the bridge, the killing is done with pesos. We can look at the era of high-volume drug trafficking as an era of high-volume killing, first and foremost. And we can await the day that a killer meets a killer’s justice.

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Juárez

- Crime

- El Paso