This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

On a sweltering Thursday morning in mid-April, Jack Pierce was picking his way among the stalls and pushcarts of the old market in Veracruz, Mexico, sidestepping baby pigs and turkeys and half-dead iguanas, when an old man in a tattered serape appeared out of nowhere. Waving a bony finger, the man demanded to know why Pierce, the esteemed manager of El Club de Beisbol Rojos del Aguila de Veracruz (the Veracruz Red Eagle), had failed to signal for a bunt in the sixth inning of the previous night’s game with Los Tigres de Mexico (the Mexico City Tigers). “Esto no es beisbol,” the man declared, shaking his head somberly. He had listened to the game on radio, not able to afford 11 pesos (less than $4) for a bleacher ticket, but he nevertheless had a strong opinion as to why the home team lost—and so did a lot of others, judging from the crowd that began to gather on the sidewalk.

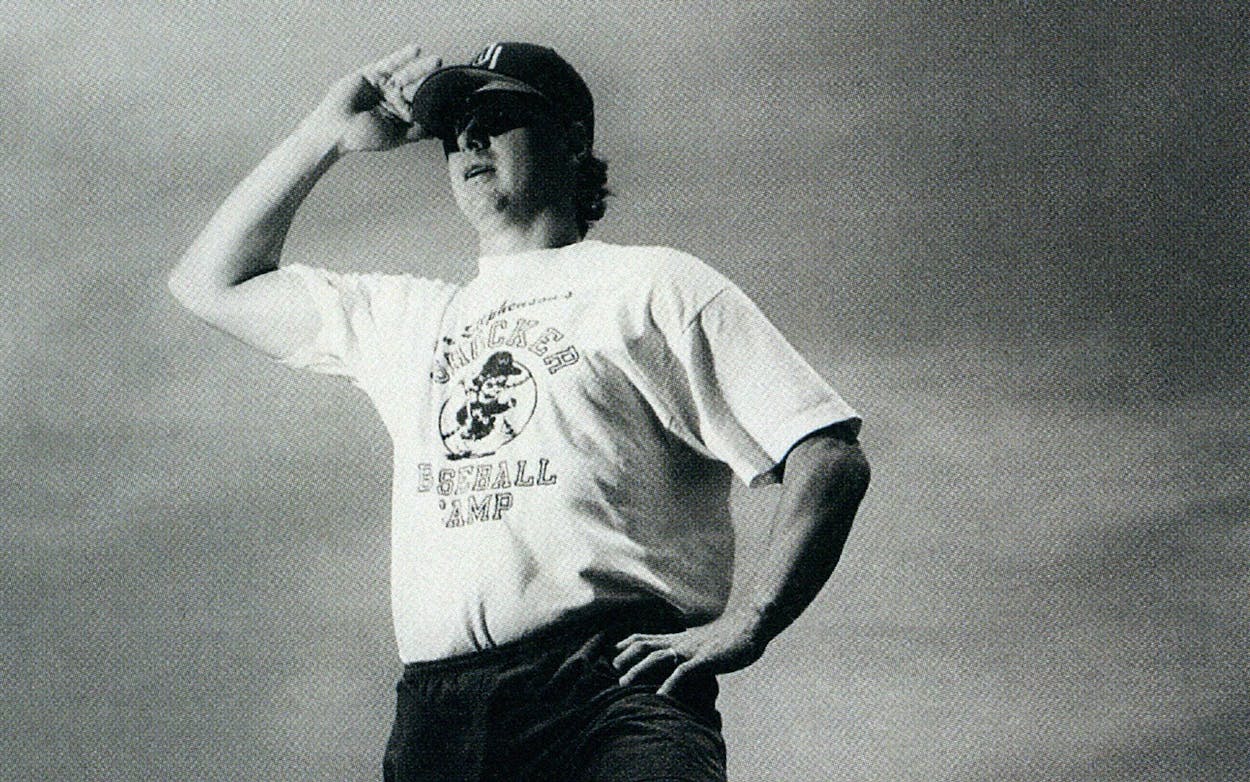

Everyone at the market seemed to know Pierce, a large and surprisingly graceful man easily identifiable in his Rojos del Aguila baseball cap and white coach’s shorts. “Hey, Yack,” voices had called out as he strode among the prodigious rows of fruits and vegetables. Pierce stood now with his massive arms folded, a foot taller and eighty pounds heavier than most of the jabbering fans who had clustered around him, listening patiently as each of them offered advice and counsel. As any aficionado of beisbol must have known, the situation in question had clearly called for a bunt: a scoreless tie, a man on second, no one out, the fabulous cleanup hitter Phil Stephenson on deck. If the Red Eagle didn’t move the runner to third, then obviously the Tigers would walk Stephenson and set up the double play. Which is exactly what happened. El Aguila went on to lose 7–0 to Los Tigres, its second defeat in as many games.

When the old man in the serape had finished his critique, Pierce said something in Spanish—he told them he probably would have bunted too if he had had all night to think about it—and everyone laughed, no one harder or with more relish than Jack Pierce. This is what Pierce loved about Veracruz: the market, the people, the way they enjoyed mixing it up. In few other Mexican cities were fans as knowledgeable about the subject of baseball—or as critical.

Like most American players who end up in Mexico, Pierce had enjoyed a short but undistinguished major league career. In the seventeen years that he bounced around professional baseball, he had played two seasons with the Atlanta Braves and another with the Detroit Tigers, and he had been with minor league teams at every level. Pierce had been coaching or playing on and off in Mexico since 1974, when the Braves optioned him to Los Charros de Jalisco (the Jalisco Cowboys). (Most major league teams have working agreements with teams in Mexico similar to those they have with minor league teams in the United States. Players optioned to Mexico remain the property of the major league club until the club sells, trades, or releases them.) In 1976 Pierce was sold to the Mexican League club in Puebla, and for the next ten years he moved almost with the seasons, playing with León in the Mexican League; Mazatlán in the Pacific League; San Jose, California, and Spokane, Washington, in the Triple A Pacific Coast League; and even with a team in Japan. Pierce was a baseball gypsy, though one who had flirted with immortality. The 54 home runs that he hit with León in 1986—at age 36, no less—continue to be a Mexican League record. “I’m not the Babe Ruth of Mexico,” he told me, “but I guess you could call me the Roger Maris.”

Mexico could be the end of the road for a baseball player, or as it had been for Pierce, it could be another road entirely. Most of the year, Pierce lived in León with his wife, Gloria, who is a Mexican national, and their daughter and two sons. Another daughter, born out of wedlock nearly eighteen years ago, lived with her mother in Mazatlán—a reminder that life for a baseball player involves complications not covered in the standard contract. Since 1987 Pierce had been employed as a scout for the Braves, and for the past two years the Braves had permitted him to manage the Red Eagle. But this would be his last season in Veracruz. The Braves had signed an agreement with Los Tecolotes de los Dos Laredos (the Owls of the Two Laredos), so if Pierce returned to the Mexican League in 1994, it would be with Laredo. In the meantime, Pierce intended to make the best of things. He had rented an apartment a few blocks from the ballpark and was resigned to seeing his wife and children only on school holidays or when there was a break in his schedule.

Making do in Mexico was largely a matter of attitude, and Pierce had the attitude down pat. He had known the pains as well as the pleasures of the country and had recognized that a certain balance was required, an adjustment to the culture and pace of life. Nothing really bothered him—not even losing, which the Aguila did fairly often. When the team bus broke down on the road to Torreón earlier in the season, Pierce accepted it with the same calm detachment he exhibited when his star pitcher got his throwing arm ripped open by a dog while jogging on the beach: Hey, this is Mexico! When the team traveled—usually late at night, sometimes fifteen to twenty hours at a stretch—Pierce assigned the twelve sleeping berths on the bus to the players who would be seeing action in the next game and took whatever seat remained, sometimes sitting on an ice chest. When the team played on the U.S. side of the border, as it did for one game during each series with Laredo, Pierce gave his players the day off to go shopping.

One of only two American managers in the league, Pierce spoke both Spanish and English, which made him a unique asset to the Red Eagle. So did his contacts. Mexican League rules permitted each team to have four non-Mexicans on its roster. These so-called import players were usually the heart of the team; the drop-off in quality between them and the Mexican nationals was dramatic. Unlike some ball clubs in the Mexican League, Veracruz had no agreement with an American franchise, so it relied on Pierce to find available foreign talent.

In 1992 the Red Eagle failed to make the play-offs, finishing sixth in the eight-team southern division despite having one of the league’s best pitching staffs. As a rule, the local population produced more pitchers than position players or sluggers. In the off-season, therefore, Pierce had concentrated on finding import players who were hitters and fielders. He had kept his best import pitcher, Manny Hernandez, who had played for the Houston Astros in 1986 and 1987. To fill an opening at third base, Pierce had convinced the Aguila management to purchase the contract of Germán Rivera, who had played the last two seasons with Los Sultanes de Monterrey (the Sultans of Monterrey) and had once played in the majors for the Astros and the Los Angeles Dodgers. For center field, he signed speedy Dwight Taylor, who had led the Mexican League in stolen bases while playing for Laredo in 1991 and had once played for the Kansas City Royals. For the key position of first base, Pierce worked a trade with Los Rojos Diablos de Mexico (the Mexico City Red Devils) and acquired Francisco Meléndez. Meléndez, who had done short stints with the San Francisco Giants and the Philadelphia Phillies, was an excellent fielder—he had what baseball people call sweet hands—and a dependable power hitter.

Unfortunately, Meléndez broke one of those sweet hands just before the Aguila was to begin spring training. After a series of frantic telephone calls, Pierce was able to find Phil Stephenson, a first baseman who had spent part of the last four seasons with the San Diego Padres. Stephenson wasn’t as good as Meléndez on defense, but he was a better hitter. If Meléndez recovered from his injury and was able to return, Pierce would have to decide which import player to cut. In the meantime, the Aguila appeared set—not necessarily a better team than last year’s but at least no worse.

Jack Pierce was big brother, father-confessor, and champion of hopeless causes to the men who played for him. He treated them all like adults—even the young farm boys from rural Mexico who had little or no education and were away from home for the first time. Pierce stood up for them against management, allowed each man to establish his own training rules, and never imposed a team curfew. Yet if a player failed to perform, Pierce fired him. The morning after the series opener with the Tigers, he sacked relief pitcher César Díaz, who had blown a four-run lead. Díaz, a Mexican national, was a loudmouth who didn’t stay in condition and refused to work on technique. At thirty, in the latter stages of his career, he was probably finished as a professional ballplayer. “If you’re gonna talk the talk,” Pierce told his men, “you better walk the walk.”

Veracruz isn’t the worst city for an American ballplayer, though it ranks right up there. It is hot, cramped, smelly, noisy, dirty, and old—especially old. It has been on the map since 1519, when Hernán Cortés and the Spanish conquistadores first landed in what they called New Spain, but it offers little of the colonial charm or natural beauty of other Mexican cities. Veracruz is Mexico’s principal seaport on the Gulf of Mexico and supports both a large fishing fleet and a naval yard, but its beaches are littered with filth, and the surrounding countryside is low, swampy, and infested with mosquitoes. A few modern resort-style hotels sit on the shoreline south of town, but the hotels near El Centro—where the ballplayers and most Mexican tourists stay—are run-down, and they make almost no attempt to accommodate the taste of gringos. Flying directly to Veracruz from anywhere in the U.S. is difficult and expensive. Everything in Veracruz is expensive. A large burger with fries and a drink costs 20 pesos (about $6.80). A two-bedroom apartment costs 3,000 pesos (about $1,000)—if there’s one available.

Ball games in Veracruz—or anywhere else in Mexico, for that matter—have a wacky, gaudy, Fellini-esque quality that teeters somewhere between illusion and madness. For one thing, batboys are often old men. The Aguila’s batboy is a gnomelike fellow named Carlos who looks as though he would be comfortable in the bell tower at Notre Dame. Nobody is sure of Carlos’ age, but he has been the team’s batboy for more than thirty years and doubles as its equipment manager and batting-practice catcher. The Veracruz baseball stadium looks like something that has fallen off the top of a Mexican wedding cake. The bleachers are painted in soft pastels, and the seats are lavender; the infield dirt is bright orange and as hardpacked and as unforgiving as concrete. Although the stadium’s capacity is seven thousand, fewer than two thousand fans usually attend the Aguila’s games, even when the opponent is a top team like the Mexico City Tigers. The scarcity of fans, however, does not diminish from the general atmosphere of chaos. When the loudspeakers are blaring bad Mexican rock music and orange clouds of dust from the recently raked infield are billowing through the stands like fog from a zombie jamboree and the fans are beating their beer bottles with sticks, stomping their feet, and whistling through their teeth, the effect is disorienting and disturbingly erotic.

The Aguila is something of a league orphan, having moved to Veracruz two years ago from San Luis Potosí. The owner of the team lives in Mexico City and spends most of his time operating car distributorships and other businesses in various parts of the country. Under his stewardship, the Aguila does almost everything second-rate. The players are poorly paid—even by Mexican League standards—and fringe benefits, such as airfare for star players to fly on long road trips, are extremely rare. In 1993 first baseman Phil Stephenson’s $5,000-per-month salary was the club’s highest. Other import players made between $3,500 and $4,000, and most Mexican nationals earned less than $1,500—some much less. By contrast, the Mexico City Tigers paid about $8,000 to import pitcher Mike Smith, who had less major league experience than Stephenson. Even the Tabasco Olmecas, one of the league’s poorest franchises, shelled out $7,000 for Rusty Tillman, a journeyman outfielder who had played professional baseball for eleven years. Like most clubs, the Aguila pays Mexican income taxes for its import players, but it is up to each individual to deal with the Internal Revenue Service.

The Aguila furnishes its players with a hotel room, a cap, a shirt, and a pair of pants; any other equipment has to be supplied by the players themselves. On the road, players receive 50 pesos a day (about $16) in meal money, but when the team is in Veracruz, each man pays for his own food. The Aguila’s uniforms are made of cheap cotton and are coming apart at the seams. While wealthier teams like the Tigers stitch the players’ names on the backs of their shirts, the Aguila stitches the name of a popular brand of mineral water. The home team’s clubhouse (there is no visitor’s clubhouse) is tiny and poorly ventilated, and the showers—when they work—never have hot water.

Such conditions seem primitive to the American players, but to the Mexican nationals, Veracruz is almost luxurious. Baseball on this level—comparable to Double A in the U.S.—is almost beyond their comprehension. The $5,000 or $6,000 that a young Mexican can make for playing five months of ball might be more than his father or grandfather made in a lifetime. A lot of them are still getting used to indoor plumbing. The reason that some Mexican League dugouts smell like urinals is because they are: Shallow troughs have been installed in them for native players who would rather relieve themselves on the spot than walk a few steps to the conventional baño.

All the import players—even those who grew up in Spanish-speaking countries—are better educated and far more sophisticated than the Mexican nationals, who come across as bumpkins and sometimes dimwits. The younger Mexicans like to put on their uniforms before going to the dining room for a meal, apparently hoping to impress someone. (“My God!” groaned Phil Stephenson. “I haven’t seen players do that since the rookie league.”) Two native players who grew up in the mountains are convinced that coconut milk is a magic elixir that attracts women, and they carry a jug of it around the lobby of the team’s hotel.

Clearly, the Mexican players have almost nothing in common with the imports—including, strangely enough, the game of baseball. “They play the game backward,” said Mike Smith, who has been pitching in Mexico since he was released by the Baltimore Orioles in 1990. “Native pitchers throw curves instead of fast balls, and they don’t understand the strategy of a sacrifice or a hit-and-run.” Unlike the imports, who are usually in pretty good shape, the stereotypical Mexican ballplayer is short, fat, slow of foot, and chronically lazy. The good athletes in Mexico play soccer rather than baseball.

Pittsburgh Pirates scout Angel Figueroa, a native of Mexico, said recently, “Among Mexican ballplayers, you rarely find the combination of running speed and power.” That’s why more than half of the 58 Mexicans who have made it to the major leagues since 1933 have been pitchers. The most famous of that group, former phenom Fernando Valenzuela, was the subject of a story in the April 16 issue of the News, Mexico’s English-language daily. His is a tale of triumph over disaster that should gladden the heart of any Mexican Leaguer with big-league aspirations. Burned out after a decade with the Dodgers, Valenzuela returned to Mexico in 1991 and struggled just to keep his job with the Jalisco Charros. But this year, the Baltimore Orioles have given him a rare second chance, and he is pitching again in the majors. One might suppose that word of Valenzuela’s fate would be of great interest to the import players, but in fact it has created hardly a ripple. These are players who once performed on the margins of big-league baseball, most of them for a mere blink of time. It is difficult for them to identify with a faded superstar.

On Thursday afternoon, before the final game of the series with the Tigers, Aguila first baseman Phil Stephenson was sitting on a rubdown table in the team’s training room, rubbing a sore shoulder. The room smelled of liniment and mold and was barren except for a few rolls of tape, some bottles of pills, a chest of ice, and a picture of the Virgin of Guadalupe. The dressing room next door was nothing more than an open space with faded green walls, a few folding chairs, and some hooks on which to hang clothes. Having spent seven seasons in the minors, Stephenson had seen some sorry places, and Veracruz was one of them. In the Dominican Republic, he had lived in a thatched hut—Gilligan’s Island, he called it. In Pittsfield, Massachusetts—“a town that names itself,” he recalled ruefully—the only lodging available was an apartment at the top of a ski lift ten miles from town. “The secret of this game,” he said, “is rolling with the punches.”

Stephenson’s latest chance to test that theory had begun six weeks before, on March 9—the longest, loneliest day of his life. He left his wife and home in Wichita, Kansas, at five-thirty in the morning, changed planes twice, and arrived in Veracruz twelve hours later, just in time for a scheduled workout. Too tired to play ball, he went to sleep at his hotel, then traveled to the stadium two days later for an exhibition game. Because of one of the periodic gale-force winds that locals call los nortes, the game was canceled, which was fine with Stephenson: The shock of being in Mexico was almost more than his system could handle. In March 1992 he had been in training camp with the San Diego Padres, earning $130,000 a season. Now he was in a grubby Mexican seaport, making $5,000 a month. If he didn’t get back to the big leagues before long, his career was probably over. Baseball had been the center of Stephenson’s life for 26 years, since he first started playing Little League in Guthrie, Oklahoma. He had played college baseball at Wichita State University, where his brother, Gene, is the head coach, and had signed his first contract with the Oakland A’s in 1982. Who would have dreamed that 11 years later—at the still tender age of 32—he would be struggling for his professional life in some Mexican rathole?

Stephenson spoke almost no Spanish and knew little of the native culture or customs. His room at the Howard Johnson’s was small and dreary, its only window overlooking another guest’s dirty laundry. Down the street at the beach, he was revolted by what he took to be an open sewer pipe spewing effluent directly into the Gulf of Mexico. The humidity and dust played hell with Stephenson’s sinuses, and his stomach churned at the thought of digesting the local cuisine. For the first month, Stephenson survived almost entirely on burgers, pizza, and other fast foods from restaurants with American names.

“I’m just trying to look on the bright side,” he told me gamely. “I needed a job. The Padres had released me, and I hadn’t heard from anyone—not even a Triple A club. If Jack Pierce hadn’t called, I’d be sitting at home, out of baseball. I know that hardly anyone makes it back to the majors from this place. It’s a long shot. But at the moment, it’s the only shot I’ve got.” It would be an even longer shot, Stephenson calculated, if a major league team didn’t contact him by July 4. That was a significant date because the Mexican League season ended a month later and league rules prohibited teams from selling players in the final month of the season. “If nobody picks me up by July 4,” he acknowledged, “it probably won’t happen.”

In the lingering twilight, while the teams took batting practice and warmed up for their customary eight-thirty start, Stephenson killed time by watching the activity of a large mound of red ants that lived exactly where the first baseman was supposed to stand. The ants remained relatively tranquil and workmanlike until the fifth inning, when the ground crew raked the infield and sent the colony scurrying. Studying the deliberate and unhurried manner in which the ants recovered and regrouped helped Stephenson get through the late innings. “On the field, I just try to forget [everything] and play ball,” he said. “But then I come back to the clubhouse and the reality sinks in. This wouldn’t even pass for Class A ball in most places.”

Still, after a month and a half in Mexico, things were looking a bit better for Stephenson. His wife, Kim, had joined him at the Howard Johnson’s, and they were looking for an apartment where they could at least cook some of their meals and enjoy a few of the comforts of home, including an opportunity to watch ESPN, Phil’s favorite network. Along with not having a car, the toughest part of living in a foreign country was not being able to get up-to-date major league baseball news. But Stephenson was resourceful, a bright guy with a talent for working the angles. He had, for instance, used his limited Spanish to discover a way to save money on long-distance calls and bank transfers.

Phil and Kim Stephenson had the blond good looks of a classic all-American couple: He resembled actor John Heard, while she would have been Central Casting’s version of a head cheerleader. Married less than two years, they had no children, which was why Kim was able to join Phil in Mexico. With the exception of a few months in 1992 when Phil was temporarily optioned to the Padres’ Triple A team in Las Vegas, this was Kim’s first experience as a baseball wife anywhere outside the major leagues, and she was doing her best to be a good soldier. As expected, Phil had become the Aguila’s best hitter and its star player. Strolling the streets of Veracruz, the Stephensons were sometimes stopped by timid fans with downcast eyes who thrust pencils and paper in Phil’s direction—not a word spoken—and then retreated with their prized autograph. It was all very strange.

Like Stephenson, the other three import players were in their early thirties, which meant their chances of returning to the major leagues were remote. A remote chance, however, was enough to keep them playing the game. Dwight Taylor, the Aguila’s other American-born import, was far less self-sufficient but in his own way more serene and oblivious to his fate. Taylor had nine children to support back home in Jackson, Mississippi, and no off-season job. If his wife was able to join him in Veracruz, it would be for only a short visit. The Aguila paid Taylor $4,000 a month—$1,000 more than what he would have made in Triple A. If he decided to stay in Mexico and play winter ball with Los Mochis in the Pacific League, he would clear about $32,000 for eight months’ work. “Not too shabby, eh?” he said, smiling. In 1981, after his junior year at the University of Arizona, Taylor had quit school to sign a contract with the Cleveland Indians, dreams of immortality swirling in his head. But in twelve years as a professional—a span that included employment by five different major league organizations—he had spent a grand total of twenty days in the majors, all in the spring of 1986 with the Royals. In 1991 the Braves optioned him to the Owls of the Two Laredos in what at the time seemed to be a major break in his career. “If you can come down here and have a good year, it’s a way back to the big leagues,” he said. Actually, Taylor had had a great year with Laredo, leading the league in stolen bases and hitting .327, but instead of calling him to the majors, the Braves released him. The following year, Taylor caught on with the Cincinnati Reds’ Triple A team in Nashville, but he didn’t see much action and didn’t play very well. At age 33, he was back in Mexico, still optimistic that the best was yet to come.

In contrast, Germán Rivera, an import from Puerto Rico, found little comfort in anything connected to his present situation. To hear Rivera tell it, beisbol had been very, very bad to him. In 1989, after it had become apparent that neither the Dodgers nor the Astros appreciated his talents, Rivera had played a year in Japan. Though his salary that season was $200,000, plus an opportunity to make another $110,000 in bonuses, he bitterly resented the fact that the Japanese had forced him to participate in the team’s conditioning program and to take daily batting practice. “Every day they make you hit, you know?” he complained, his handsome face twisted into what seemed to be a permanent frown. “Ten minutes right hand, ten minutes left hand. Every day!” He wouldn’t even be in Mexico, he hinted, if it hadn’t been for a case of chicken pox that had cost him his power—and his job—in Triple A baseball. What’s more, he now had reason to believe that the Mexican League was using a softer brand of baseball, one that favored pitchers, thereby confirming his long-held suspicion that “they” were conspiring to keep him from reaching his potential as a slugger.

The foreigner who had adjusted most comfortably to Mexico was Manny Hernandez, who at 32 realized he had hardly any chance of making it back to the majors. Originally signed as a 17-year-old by the Astros in 1979, Hernandez cried every night his first year away from his home in the Dominican Republic. He eventually pitched two years for the Astros—and one inning for the New York Mets—and for the past two seasons, he had been one of the Mexican League’s better pitchers. In the off-season he lived in Ocala, Florida, with his wife and daughter. “I like playing here,” he said. “There’s not much pressure. Here, we play more freely.” As long as someone was willing to pay him, Hernandez planned to continue playing in Mexico.

The Aguila won the final game of its series with the Tigers—an uncharacteristic note of optimism that preceded a road trip to hell. In the wee hours of Friday morning, the team boarded a bus for an all-night trip to Villahermosa, the capital of the state of Tabasco and the home of the Olmecas, who had finished even lower in last year’s standings than the Aguila. Villahermosa had a reputation among players as the armpit of the league—an isolated and supposedly unattractive ranching and oil town on the banks of a sluggish river miles from the coast, near where the narrow southern part of Mexico begins to fishtail into the Yucatán Peninsula. The people of Villahermosa were said to be hostile black Indians—descendants of the Olmecs, the earliest civilization in Mexico—and the climate was subtropical and savagely hot. Jack Pierce had told his players horror stories of split-bill doubleheaders there. The first game usually started at eleven in the morning and the second at five, with maybe an hour to rest in between. They were played under an unrelenting sun, in humidity so dense that players wondered why they weren’t issued snorkels, before a savage crowd who—if you believed the rumors—ate human hearts like popcorn. “By the second game, you’re almost too tired to move,” Pierce had said. “Whoever scores first almost always wins.”

Before boarding the bus, Pierce had gone back to his apartment to pack and say good-bye to his family, who had spent their just-concluded Easter vacation in Veracruz. He took his kids out for burgers and sodas, tucked them into their beds, and began stuffing cans of “diet food”—sardines and tuna—into his suitcase among the shirts and shorts and shaving gear. Pierce’s mind was already drifting down the long road to Tabasco. He felt good about beating the Tigers, but he was preoccupied with another matter: his ongoing dispute with the Aguila management. Francisco Meléndez, the first baseman with the sweet hands who had been injured in the preseason, had recovered, and the team owner wanted him activated at the end of the road trip. To make room for Meléndez, the owner wanted to release Dwight Taylor. In Pierce’s opinion, that decision wasn’t fair to Taylor, who had lived up to his part of the contract. It wasn’t even sound baseball—releasing the team’s best outfielder and base runner for the expediency of adding another power-hitting first baseman. After all, Phil Stephenson had been performing satisfactorily at first base and was among the top hitters in the league. How to resolve the situation? In baseball, Pierce believed, a man went where he was scheduled to go and did what he was told. Nevertheless, he didn’t like it.

While Pierce and most of the other players were climbing aboard the bus for Villahermosa, Stephenson enjoyed a late supper with his wife at a Veracruz restaurant and then returned to the Howard Johnson’s for a good night’s sleep. Stephenson and Germán Rivera had received permission to fly to Tabasco the following day. They would have to pay their own fare—$120 one-way on AeroCaribe—but from what they had heard about the road trip this seemed like a bargain. The Aguila’s bus was in the repair shop, so the players would be traveling on a commercially chartered bus: no sleeping accommodations, no toilet, no air conditioning, hardly any place to stop along the way. The trip would take them across some of the bleakest and least attractive parts of Mexico. Stephenson and Rivera both had clauses in their contracts that required the team to fly them to a specified number of road games—Rivera had been guaranteed six, Stephenson four—but they were saving those flights for more arduous, expensive journeys, such as the twenty-hour bus rides to Yucatán and the long trips to northern division cities like Torreón, Monterrey, and Laredo.

The flight to Villahermosa was delayed several hours, so the two men arrived at their hotel just in time to change into their uniforms and catch the team bus to the stadium. Despite its reputation, Villahermosa was a surprisingly attractive city, lush and vibrantly green, with palms, flowering shrubs, and rolling hills. It was also a hotbed of activity. Some sort of fiesta was just kicking off as the bus left the hotel, and every street in town was either choked with traffic or blocked off by a parade that seemed to have no beginning and no end. Less than an hour before the game was scheduled to start, the bus was still crawling along side streets, the driver seeking an alternate route to the ballpark. Players checked their watches nervously, but Pierce didn’t appear concerned. His position was: Hey, they can’t start without us.

By the time the Aguila’s bus arrived, the weather couldn’t have been better. A cool, fresh, fragrant breeze blew in from right field—an omen, perhaps, that all was not right. “This is not how it’s supposed to be,” warned Rusty Tillman, the Olmecas’ 32-year-old slugger. “The heat down here almost always takes it toll.” Tillman warned too about the fans, though as they drifted into the stadium and found seats, they appeared docile enough. “Tabasqueños are wild and a little crazy,” he declared. “They don’t take crap from nobody, not even their own players.” Tillman and one of his teammates, Todd Brown, wandered over behind the batting cage and cozied up to Jack Pierce as the Aguila took batting practice. Almost any time the Aguila visited another ballpark, the Americans on the opposing team sought out Pierce for advice or just to hear the voice of someone who spoke English and understood the game of baseball. Tillman and Brown had been arguing about which hand in a batter’s grip supplied the power, and they wanted an opinion from the master. “The bottom hand is the power hand,” Pierce told them straight out. “The top hand just guides the bat. The bottom hand gets to the ball first, makes you stay behind the ball.”

For six innings, the game was close and uneventful, and several thousand Tabasqueños in the stands seemed moderately calm, if slightly restless. But in the seventh inning, trouble hit like a summer storm. A ball that should have been a double play bounced off Germán Rivera’s glove, allowing the Olmecas to score what appeared to be the go-ahead run, and the crowd erupted into a wild celebration. Then the third-base umpire belatedly called the ball foul. Suddenly, the manager of the Olmecas charged out of the dugout, kicked the dirt around third base, and shouted insults until the umpire had heard enough and thumbed him out of the game. With that, the bleachers seemed to explode. Waving fists and hats and screaming profanities, the fans began pelting the field with bottles, paper cups, ice, and wedges of oranges. As team officials tried to restore calm, Pierce and his players retreated to the shelter of their own dugout. After a delay of about ten minutes, the public address announcer warned the fans that if they didn’t stop throwing things, the game would be forfeited to the visitors. “They’re just bluffing,” Pierce reassured his players. “If they forfeit the game, we won’t get out of here alive.” Sure enough, the threat seemed to work. The fans stopped throwing things and the game continued, though at a nervous and uneasy pace: another spark could set off a full-scale riot. In the ninth inning, when Dwight Taylor was called out on a close play at first base, Pierce quickly jumped between Taylor and the umpire, quelling the confrontation. After two more outs, the Aguila went down to defeat, 2–1.

The following afternoon, as the teams went though their warm-ups before the second game of the series, pieces of fruit and crumpled cups remained scattered in corners of the field, suggesting that the battle had not ended but had merely been recessed. In a show of bravado, one of the Aguila’s Mexican players picked up a piece of fruit and began to suck out the juice, but you could tell that he would just as soon be somewhere else. An eerie silence crackled over the stadium as the crowd began to trickle in and take their seats, and it continued through the early innings of the game. Then a barrel-chested man in a soiled T-shirt and a sombrero stood up in the left-field bleachers and began a loud continuous dirgelike whistle that unnerved everyone on the field. Other fans picked up the whistle. In the stands behind home plate, a small dark man in sunglasses began beating a tom-tom while a companion blew a tin horn. Wild Indian yelps reverberated from another part of the stadium, and from somewhere just beyond the left-field fence came an explosion that one hoped was fireworks. For the remainder of the game, the mad whistler in the sombrero ran through the stands, exciting waves of whistles and yelps and bloodcurdling oaths. The ruckus so disturbed the Aguila that two of its relief pitchers walked three consecutive batters in the eighth inning, one of whom later scored the Olmecas’ winning run. Veracruz lost again.

On Sunday, the starting time of the game was moved forward to eleven in the morning—an attempt, perhaps, to intimidate the team from Veracruz with the threat of heatstroke. But it didn’t matter: an unexpected cloud cover and a northerly breeze kept the temperature mild. Anyway, the Aguila couldn’t have been colder if they had spent the night in a beer cooler. Nothing was working for Jack Pierce’s team. Stephenson, in a sudden slump, was barely able to hit the ball out of the infield. Taylor struck out with a runner on third base, then misplayed a fly ball in center field. Sensing that the enemy was in the final spasms of death, the Villahermosa fans were relatively subdued—except for four young women seated behind home plate who amused themselves by making unflattering sexual comments about the Aguila’s hitters. The Aguila lost its third game in a row, its eleventh in fourteen games.

Pierce didn’t say much on the way back to the hotel, and neither did anyone else. The players looked sheepish and thoroughly whipped, a sad and demoralized group in ragged uniforms that hadn’t been washed in three days. In the morning the players would board the bus again for another long ride up the coast to Minatitlán, where they would struggle through another three-game series before returning to Veracruz. Most of them were looking forward to a night off, to a few beers and maybe a walk on the wild side. But as the bus pulled into the hotel parking lot and the players began to gather up their equipment and head for the door, Pierce suddenly stood up, faced his men, and blocked the aisle. Some players inched back and took their seats, while others waited in the aisle; everyone avoided the manager’s eyes. Pierce looked them over for a minute, then said in his customary low-key way, “You’re a better team than this. Keep your heads up.” Pierce paused as though he wanted to say something else—maybe to drop a hint that dark forces were at work in the front office, that things were not necessarily as they seemed—but he apparently decided against it. “Have your dirty uniforms piled up in the lobby in one hour,” he said brusquely. “The bus leaves for Minatitlán at nine in the morning.”

On Monday night, the Aguila lost again, this time to Los Petroleros de Minatitlán (the Minatitlán Oilers), but as it turned out, that was the least of Jack Pierce’s worries. Before the game, two Americans on the Minatitlán squad approached Pierce and asked him to do something that he knew would probably be misinterpreted. They asked him to intervene on their behalf with the owner of Los Petroleros, who—despite Mexican League policy—had decided to deduct 30 percent of his American players’ salaries for Mexican income taxes. The Americans, who spoke no Spanish, wanted Pierce to act as their advocate; they confided to him that they were considering going on strike. “Hey, don’t even think about that!” Pierce warned them. “If you strike, they’ll ban you from this league for life.” The tax problem was the players’ own fault—they had signed contracts permitting such deductions—but against his better judgment, Pierce agreed to meet with the owner. The following morning, the owner telephoned the league office in Mexico City and complained that Pierce was instigating labor unrest among his import players. That afternoon, the owner of the Veracruz club flew unexpectedly to Minatitlán, and that night, fifteen minutes before the start of the second game of the series, he walked onto the field and fired Pierce. By the time the Aguila had lost its fifth straight game, Pierce was long gone.

The official reason for the firing was the Aguila’s poor record: thirteen wins and eighteen loses, which put the team in a tie for sixth place in its division. But hardly anyone bought that explanation. Anyone who knew baseball knew that inferior talent was the reason the Aguila lost. No manager could have done much better. Pierce wasn’t cashiered for his failure to articulate the sweet science of baseball but because he was perceived by his boss as a friend of the grunts. In other words, he wouldn’t play ball.

Two days later, when the Aguila returned to Veracruz, Dwight Taylor was informed that his services were no longer required. The team couldn’t have picked a worse time to break the news: The day Taylor was fired was the same day his wife arrived in town for a visit. Though the Aguila’s management had known for at least a week that Taylor’s days were numbered, it nevertheless allowed his wife to make the long and expensive trip from Mississippi. A few days later, Taylor found another job with the Mexican League team in Aguascalientes.

By the time the first half of the league season ended on May 26, the Aguila had climbed to fourth place. Yet life in Mexico was getting progressively worse for Phil Stephenson. He had been replaced at first base by Francisco Meléndez and was now listed as the Aguila’s designated hitter. One of those nameless flulike Mexican illnesses had sidelined him for nearly two weeks, sapping his strength, and his batting average had dropped from .400 to .360. In early June, Stephenson was contacted by the Texas Rangers and offered an opportunity to play for their Triple A franchise in Oklahoma City—half an hour from his hometown and a phone call away from the big leagues—but the Aguila owner quashed the deal by demanding money and a player to replace him. Soon after, the team gave Stephenson a few days off to accompany his pregnant wife back to Wichita. After watching his brother’s Wichita State team play in the finals of the College World Series, Stephenson forced himself to catch a plane back to Mexico. “It was almost more than I could do,” he said. “I came back down here with just one suitcase and my baseball equipment.” By that time his batting average had slipped to .343.

The July 4 deadline came and went without Stephenson receiving a call from a major league club. He still held out a slim hope that when the pennant races heated up in late August, some contending team would be looking for a role player. “Being a role player is what I’ve done most of my career,” he reasoned. “I can play first base or outfield or pinch hit. I’m someone who won’t complain if he only plays once a week—a guy who’ll play for a low salary, maybe even minimum. It could happen. If I didn’t think I could still perform at the major league level, I’d hang ’em up right now.”

As for Jack Pierce, he has returned to what he loves best: scouting the backwaters of Mexico for the Atlanta Braves. In the weeks after his firing, he spent time in Laredo with the Braves’ Mexican League farm team. He was looking forward to traveling in Baja California and Sonora, searching remote ballparks in out-of-the-way places for the future stars of the game. His experience in Veracruz didn’t appear to have bothered him. “Hey,” he said, “that’s baseball.”

- More About:

- Sports

- TM Classics

- Mexico

- Longreads