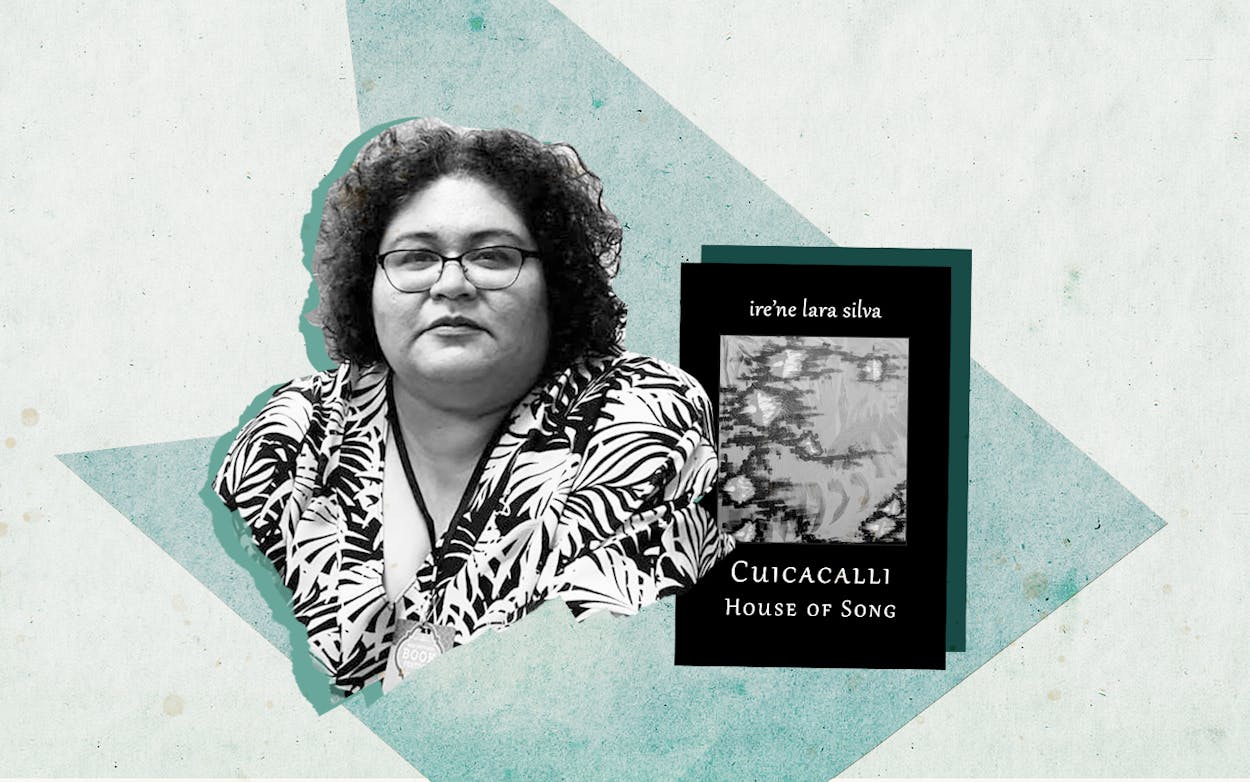

In the Aztec empire, boys as young as twelve attended the cuicacalli, or “House of Song,” to learn the sacred hymns and dances of war as preparation for their military training. Deep into the writing process of her latest collection of poetry, Austin-based writer Ire’ne Lara Silva stumbled upon the Nahuatl word. Instantly, she knew it would be the title of her book, CUICACALLI/House of Song (Saddle Road Press), which was released in April.

Much of Lara Silva’s writing centers around the beauty and pain of the Latinx experience, and she was drawn to the sense of strength that cuicacalli connotes. For most of her life, the story she was taught about her own culture cast Mexicans in the roles of villains or victims, and she wanted to flip the script.

“I want to imagine our community beyond that pain,” she says. “I’ve been meditating on our history for 25 years now, and our survival is a thing of beauty—it shows a strength that should be admired.”

Born in 1975 to migrant truck drivers in Edinburg, just north of McAllen, Lara Silva spent her childhood moving from town to town every few months as her family followed the harvest. She and her seven siblings made temporary homes in Texas, New Mexico, and Oklahoma, which made it difficult for them to attend school regularly. From first grade onward, books were one of the few constants in her life.

Lara Silva surrounded herself with science fiction novels and various works from the Brontë sisters, something her parents struggled to relate to—they were fluent Spanish speakers, but illiterate in both English and Spanish. It was easier to turn inward, she says, because of tensions between her parents and a childhood marked not only by a constant stream of arrivals and departures but by emotional and psychological abuse.

When it came time for her to go to college, Lara Silva’s only plan was to get as far away from her family as possible. Her good grades in math meant she was pushed toward an engineering degree, but within six weeks of arriving at Cornell University in 1993, she abandoned that major to pursue American studies instead. For the first time, almost 2,000 miles away from Texas, she was exposed to Latinx authors.

“I didn’t know that Latinx writers existed,” she said. “All of a sudden, I was learning about my culture, my identity, and it was this very clear perspective that felt like it had been kept from me my whole life.”

She began attending protests and marches with the Mexican American Student Alliance, where she was introduced to Chicano poetry and literature. She had been writing short stories and poems for years, but she finally felt like she was finding her voice.

Then, during her junior year of college, she was forced to drop out and return home to Edinburg when her mother began having issues with her heart. She drove her mother to her appointments, handled all of her paperwork, and worked at an Olive Garden for two years to support herself. Her parents were uninsured and, out of her seven siblings, she took on the lion’s share of the work. “It was incredibly depressing,” she said. “I stopped writing, I felt my freedom curtailed after three years of being free. Going from the Ivy League to waitressing sucked me into a big, depressive black hole.”

By 1998, her mother was on the mend, so Lara Silva decided to move to Austin. It was close enough that she could head home when needed, but far enough away for her to feel independent. She worked two minimum wage jobs to make ends meet when she decided to fully dedicate herself to writing.

She started sending her work out to publishers, facing years of rejection until 2009, when she entered and won a competition sponsored by the El Paso publisher Mouthfeel Press. Her winning manuscript became her first book, furia—a reflection on grief and loss inspired by her mother’s passing in 2001. Her short story collection, flesh to bone, followed in 2013; a second poetry collection, Blood Sugar Canto, was published in 2016. (Both poetry collections were finalists for the International Latino Book Award in Poetry.) For the first time, she was being invited to speak at universities, traveling from coast to coast and interacting with people who had read her work.“Writing stopped being about publishing something,” she said. “It became about sharing my vulnerabilities and making people feel comfortable sharing theirs.”

Toward the end of the new book’s titular poem, “Cuicacalli,” Lara Silva writes, “We cede nothing. forget nothing. the voices are here. the voices are with us. within us./the voices do not end. the singing does not end.” Her own story, the story of her family, of her ancestors, are rooted in pain and violence, but Lara Silva wants her work to look forward.

“We’ve been beaten down, but we’ve endured,” she says. “When you think about how much suppression of our history and culture there was over the years, then the indigenous foods, words, and parts of our religion that have survived are a miracle. Let’s empower ourselves with that knowledge.”