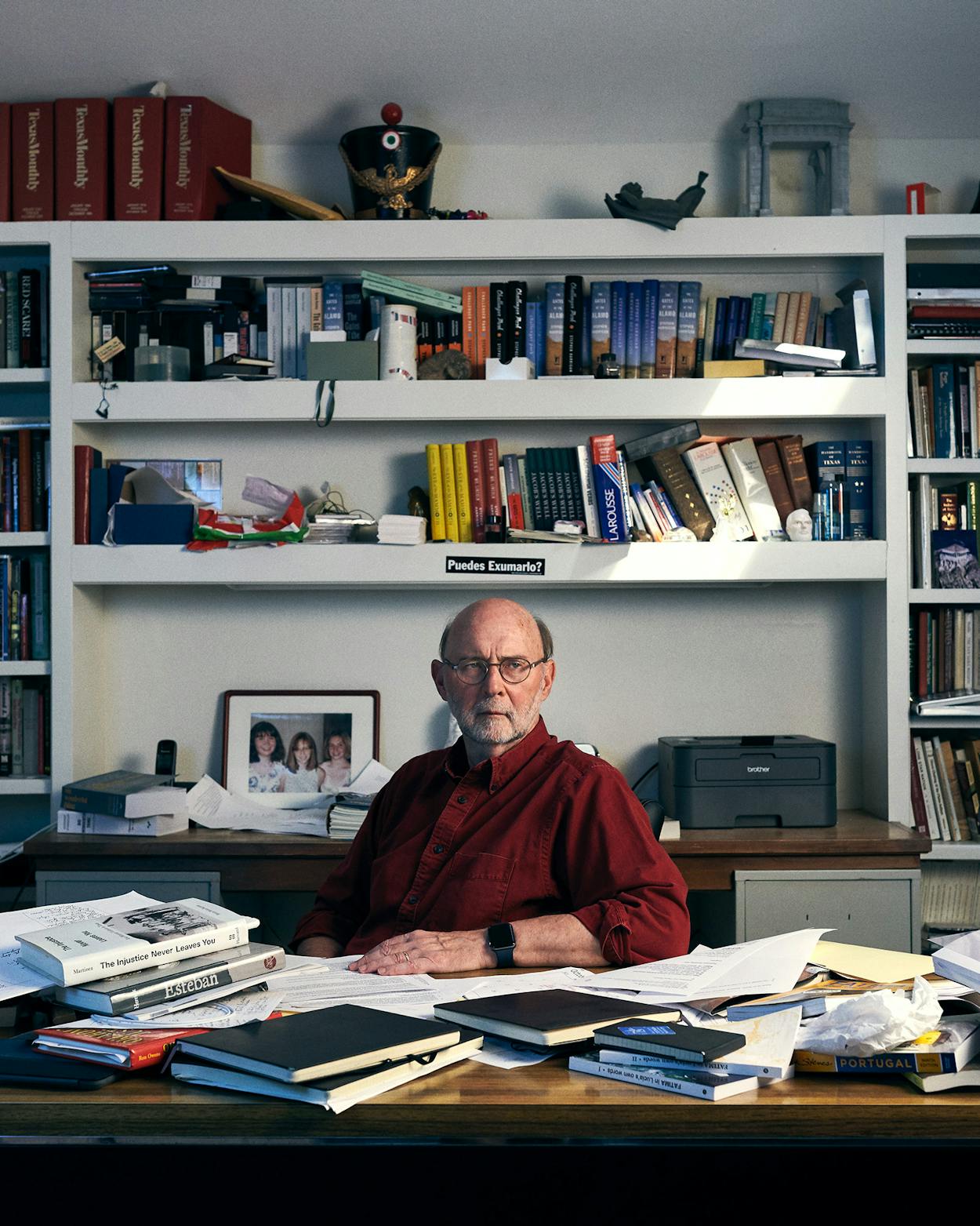

In July, as Big Wonderful Thing was being prepared for publication, the Austin author sat down with Texas A&M-College Station history professor Carlos Kevin Blanton and Texas Monthly deputy editor Jeff Salamon to discuss the creation of his epic work.

Carlos Kevin Blanton: This book was obviously a massive undertaking. It’s nine hundred-ish pages. What motivated you to do it?

Stephen Harrigan: Dave Hamrick, the director of UT Press, asked me to do it, and at first I said no, because I’m not an historian. I’m a journalist and a novelist, or at least I’ve always thought of myself that way. But the more Dave talked to me about it and the more I kept saying, “No, I don’t want to do that,” the more secretly I was feeling, “I kind of do want to do that,” because it started to feel natural to me.

I’ve lived in Texas since I was five, which means I’ve lived here for 65 years, and I’ve lived through a lot of this history, either as an observer or sometimes as a participant. And because of my work through Texas Monthly for fortysomething years, I’ve seen a lot and explored a lot, and so it began to feel kind of crazy not to take this on, even though it was a monumentally complex task. And the more I worked on it, the more I actually wrote, the more slowly my confidence built up, and I realized, “Well, maybe I can get away with this.”

Blanton: How long did you work on the book?

Harrigan: About six years. There were some other things I was working on—magazine pieces, a screenplay or two, tidying up the ending of a novel—but basically it was full-time for six years.

Blanton: Of that six years, how much was research? How much was writing?

Harrigan: I thought at the beginning of this project that I would spend a year doing nothing but reading about Texas history. But the minute I start reading stuff, that’s the same minute I start forgetting it. I don’t have the retentive memory that I should have or that I’ve always envied in other people, so I realized I had to do this in bite-size chunks. For me, each chapter ended up being like a magazine article. I had to grab reader’s attention, I had to begin each chapter with something that I found compelling and interesting, and I had to fill in where we were chronologically. It’s not that this is a series of short stories or something. It’s very much a continuum, but it was really important to me that at the beginning of each chapter you get a little injection of excitement. Once I understood that was the structure, I felt very confident because it felt very familiar.

Blanton: Have you ever spent this long on a single project before?

Harrigan: Yeah. My novel Gates of the Alamo took me about eight years, but that’s because I didn’t know how to write a historical novel. Of course, you’re reinventing the process with every book, but I think I’m getting more efficient in terms of recognizing what I need to know and what I don’t necessarily need to know.

Jeff Salamon: So you would do research on a specific topic or era, and then write a rough version or outline of the chapter, and then move on to the next, and then do research on the next subject matter and do a rough version of that chapter?

Harrigan: Yeah, that’s basically it. I knew, for instance, I would be writing about Reconstruction, so I read a whole lot about Reconstruction, and I thought a lot about it, and I did an outline, more or less as I would do for a magazine article, and I would always look for the people whose stories made that part of Texas history come alive for me. I would start with a broad spectrum of books about that period, and then I would look for those diaries and letters and experiences that really made it sing for me.

One thing that was utterly crucial was that I wanted not just to write this book, I wanted to report it. I remember one day I drove four hundred miles round trip to see the Caddo Mounds, which look like grassy lumps on a golf course, but which in fact were temples of the Caddo culture dating back something like a thousand years. I had to see it; I couldn’t not make that drive to see it. The best experiences I’ve ever had as a writer always come out of going to the places, talking to people if you can who’ve participated in whatever you’re writing about, and seeing it with your own eyes. Once it’s real to you, you can make it real to the reader.

Blanton: One thing that I really liked about the book is the experiential feel of it. Many historians do most of their work in a library or in an office. It’s sifting through documents, and it’s imagining. But you’ve gone out and touched things. Even when you didn’t need to—you’ve handled actual documents, even when they’re available online. You’ve gone to this tree to feel the markings. You’ve gone to these mounds. You’ve gone to these places. As a writer, does that unlock your imagination?

Harrigan: Absolutely. To me, the most important tool I have as a writer or as an historian is my car. I get in the car and I go to these places. For one thing, there’s the driving that gets you to the places. Then there’s the thinking time as you’re driving back and forth. What I wanted to do, I wanted to make this book as personal as I could without being narcissistic. I want the reader to accompany me to the places I saw and the things I discovered. Even when I’m doing archival research, I want the reader to be in the archive with me.

Blanton: I really enjoyed that experiential feel. I feel like it’s something more historians could work on doing. It brings readers in.

Harrigan: When I read books by historians like you I get the sense that you guys are speaking from a place of authority. As a journalist, I feel like I’m speaking from a place of discovery. I want to share with the reader the feeling of finding out stuff, rather than present myself as somebody who already knows it.

Salamon: This preference you have about discovering things and letting the reader know you’re discovering things, is that something that was developed by being a magazine writer? Because unlike being a newspaper writer, where you have a beat that you’re familiar with, a magazine writer who is writing a feature story every three months is discovering a new world each time, starting fresh each time. Did you develop that “discovery” muscle from writing magazine stories for decades?

Harrigan: When I started writing for Texas Monthly, I had the advantage of never having read much magazine journalism, and I had the advantage of writing for a magazine that was just being started by people who didn’t know how to run a magazine, so we were all inventing what we were doing. And for a long time I had no confidence in my ability, because it seemed like everybody else just wrote about things that were more interesting to readers than I did. But I was always drawn to that kind of interface of your personal experience and the objective world, and I always felt that readers, whether they knew it or not, wanted to feel that they were connecting with a real person and not just a byline.

Salamon: Your background as a journalist, as a novelist, and someone who’s just been reading about, thinking about Texas history most of your adult life, held you in good stead, I think, for a lot of this book. Were there any challenges that you felt like you were not well-prepared for, that you turned to professional historians for help with?

Harrigan: I’m not good at business. I’m not good at sports.

Blanton: There’s a chapter on football.

Harrigan: My friend Jan Reid was my spirit guide on that chapter, because I know nothing about football. I can pretend that I do in print, but I don’t. I didn’t feel as confident writing about business and politics and sports as I feel about some other aspects of Texas, and I just tried to lean on people and read things very closely and carefully and try to come up with my own ideas of what happened.

Blanton: Was there anything you learned during your research that surprised you?

Harrigan: It’s interesting when you think that recorded Texas history began 500 years ago—in 1519, literally 500 years ago—when Alonso Alvarez de Pineda made a coastal reconnaissance of Texas. But there are probably, like 15,000 years before that of human settlement, and I’m haunted by those people for whom we don’t have anybody’s name or any information other than what they left behind in places like the Alibades Flint Quarries or the pictographs in the Rio Grande and the Pecos, along the rivers there.

So I’m not sure it surprised me, but it awed me that Texas history is so incredibly deep and unreachable. All the time that I was writing about recorded history, or even history that I had lived through and seen, I was thinking about that kind of historical ballast that is way deep in the hold, that we can’t see.

Blanton: Was there anything that bugged you about the way that Texas history has been told that you wanted to address?

Harrigan: I didn’t start with the idea that I had to revise anything. I just started with the idea that I had to tell the story of Texas as I could do it, and so I didn’t have a chip on my shoulder. I was deeply aware, I hope, of the way the story has been told in the past and the one-dimensionality of it and the Anglo triumphalism that has been the story of Texas for most of my lifetime. But I didn’t set upon that course with a set of grievances. I’m keenly aware that this book will have whatever shelf life it has, and then the perceptions I have and the observations I have will be as out of date as anybody who was writing 150 years ago. I don’t want to pat myself on the back for living in the time that I live and having the awareness that anybody in this time should have.

Blanton: There are certain works that have a longer shelf life than others. I’m thinking specifically of T. R. Fehrenbach’s Lone Star: A History of Texas and the Texans. I don’t want to push you to pick a fight with someone who’s no longer with us, but did you see your book in any way correcting Lone Star or going beyond it?

Harrigan: I knew that it would go beyond it in chronology, because Fehrenbach essentially runs out of gas at the beginning of the twentieth century. But no. Lone Star is the Texas history book, like it or not, and many people feel like it’s antiquated, but it’s the monument, and I made sure that I did not read it. I mean, I read it when it came out, or shortly after, but I didn’t want Fehrenbach’s voice in my head, because It’s contagious, that pulse-pounding narrative style that he has.

I’m aware of all the controversies about Fehrenbach’s book, of course, but I didn’t think of myself as in competition with Fehrenbach or as a corrective to Fehrenbach by any means. I just want to tell the story as somebody who’s living in our time might see it.

Blanton: But the book is written in your voice, written with your perception of all of the things that have changed in the last fifty years. Was there any specific attitude that you were conscious about wanting to present in a different light than more traditional histories have?

Harrigan: “Attitude?” I’m not sure if that’s the right world. I wanted it to seem fresh. I wanted it to seem inclusive, in a non-buzzword sense. I wanted it to feel authentically inclusive. And one of the things that was so much fun for me to write about was women. When you go back to the early stages of Texas history, women are not written into it. There aren’t that many sources, but as you go along and you learn about these people and you learn about how crucial they were and how individual and fascinating so many people were, it was invigorating to write about, not as if they were a separate gender but as equal participants in Texas history. I always looked for where I could write about another woman of consequence in Texas history.

My favorite character in the whole book is Isabel Talon, the woman who came with La Salle’s colonists, about whom I think the first poem in Texas was ever written, or the first one that we know about. There are just so many people that… I’m not saying they’ve been overlooked. Other people have written about them, but I got a charge out of writing about them.

Salamon: One of the most bracing things about the book, which is really reflected in the excerpts we’ve chosen for this issue, is your forthright portrayal of the brutality that Anglo Texans showed toward Native Americans, Hispanic people, African Americans, and even fellow Anglos who were sympathizers with the Union during the Civil War. I think that’s a place where tradition-minded Texas history readers are going to be a bit taken aback when they see how evenhanded your portrait of a lot of that behavior is. I’m curious how much of that was stuff that, going into this, you knew you were going to write about in that way, and how much of this was stuff that you learned as you were doing your research for this book?

Harrigan: I knew basically what the arc of Texas history was, and there were things I found surprising and horrifying all the way through. But it wasn’t an agenda. I just tried to keep an open mind about things. And again, even though I’m pointing out all these horrific actions, I also think that it wasn’t all on the part of Anglos. The Comanches, Kiowas, Apaches . . . there’s plenty of documentation that, even when you filter out the revenge motive of white chroniclers who wanted to make the Indians look as bad as possible, you can understand that these people were playing a pretty serious game of violence.

Blanton: Those tribes’ torture techniques were imaginatively cruel.

Harrigan: It’s not “White people bad, Mexicans good, Indians good.” I’m trying to make Texas history as realistic and thoughtful as I can.

Salamon: Was there anything that you found yourself changing your mind about? Specific episodes of Texas history where your interpretation of what actually happened shifted?

Harrigan: Not so much. I’d been over this ground before a lot when I wrote the Gates of the Alamo novel, examined that pretty carefully and written about it, and there was some Texas myth-busting that needed to take place there. So I knew enough going into this to be suspicious of any chauvinistic mythic attitude that Texans have. I don’t mean to sound like I was not open to surprises, but I was aware from the outset that there’s this layer of myth that you can’t take all that seriously, and you have to get below that.

Salamon: Clearly the book reflects the reading of a lot of recent scholarship about Texas, including, “revisionist” scholarship, which is why I might describe this book as mildly woke.

Harrigan: I’m only a mildly woke person myself.

Salamon: Was there any revisionist history you came upon that you were like, “No, I don’t buy this at all. This has gone way too overboard”?

Harrigan: Yeah. Not to name names, but there are some belligerently revisionist books out there. Books with such a revisionist agenda that you just have to be a little careful about them.

Blanton: You do tread very lightly on the debate about how Davy Crockett died.

Harrigan: I have been caught in the crossfire of that debate for so long, and the reality is, nobody knows. But people care, because as I point out in the book, one of the reasons we “remember the Alamo” is because of Davy Crockett, because he was a really famous guy. The Alamo was a minor military invasion, but he was a celebrity. It’s like if Taylor Swift died in Afghanistan. People are going to pay attention.

Blanton: Do you find that there is a thread that runs through Texas history, an essence, some sort of meaning that goes through time?

Harrigan: People have prodded me all through the course of my writing this book to come up with a theme, or some large idea, and my mind doesn’t work that way. I instinctively resist the “big picture idea” of what Texas is. But I do feel like, on the question of the Texas identity or the Texas identities, a lot of it is grounded in the fact that this place has always sort of wanted to be its own thing. It seceded twice, once from Mexico, once from the United States. Unlike the other states in the United States that were flickeringly independent republics, Texas was a republic for almost a decade. It fought every minute of that time against re-invasions by Mexico. It fought the Comanches, the Kiowas, the Apaches. There was this identity, I think, throughout those many decades. Conflict forged this identity, and you still have that kind of arm’s length attitude toward a distant federal government that was in play during the Mexican Revolution times and then the Civil War times and Reconstruction times. There was a sense that we have — I say “we” in the broadest sense, I guess — of a place that wants to stand apart and wants to be thought of as different and special, whether in reality it is or not.

Blanton: At the end of the book you talk about a kind of “harmony of conflict”—suggesting that conflict is at the center of what it means to be Texan, and sometimes that conflict is violent.

Harrigan: Right, and the contention that has existed from the beginning about who is a Texan and who is not is strangely a kind of binding force, because everybody wants a piece of that action, and nobody wants to say, “No, I’m not a Texan.”

Blanton: There are a lot of people in this book whose names aren’t particularly well known, people from the margins of society that textbooks normally don’t talk about. One thing that social historians do is they use such examples of daily life to connect it to larger themes, whether they’re economic or political or ideological or religious or what have you. But I noticed that you were very reticent about hammering the reader with your own interpretations of these people’s lives.

Harrigan: I’m not geared that way. I don’t have a pronouncement gene. I don’t feel the need to say what things mean out loud or the confidence to know what’s behind that. We see it in the newspaper every day. Some op-ed is speculating on what the Democrats have to do to win the nomination or whatever, and they always sound good, but they’re almost always wrong. So I just… I’m not an op-ed person. I avoid those kind of speculations and those kind of pronouncements.

Blanton: Academic historians struggle with this notion of authority as well, which is oftentimes why when you see a lot of academic books so narrowly tailored and focused, because no one wants to speak too grandly or too broadly. They figure if you stick to a small topic, you might be on safer ground.

Harrigan: For me, I feel like authority comes from authenticity, and the authenticity comes from you recognizing who you are and what you can get away with. Whenever I’ve tried to be bigger and grander than I am as a thinker, I’ve always fallen on my face.

Blanton: Well, you don’t here. For a nine hundred-plus-page book, this is a surprisingly brisk read. It’s a real page-turner. It feels odd to ask about a book this size, but is there a lot left on the cutting-room floor that you miss?

Harrigan: I’ll tell you what—I wish I could start over, because I just read a couple books that were not published at the time that I was writing this book, and, oh man, I could do so much with the information that’s in these books. To me, to look at a book that I’ve finished writing is like looking at your picture in the high school yearbook. You just think, “I’m not that guy anymore, thankfully.” When you finish a book, you’ve got about, in my case, maybe about a two-week period of feeling, “I did it. Great,” and then after that comes the “Oh man, why didn’t I think of that?” phase. And so I’m trying not to go there.

But I keep imagining the book that could be written, the one that’s not about Moses Austin coming to Texas. It’s about Erasmo Seguin being the guy who leads him in and makes those connections. I’d love to write a book where the script is totally flipped, but I don’t know how to do that. I don’t know how to make the Native American story the primary story. And lots of historians who are working in that narrow-gauge way you’re talking about are doing exactly those sorts of things. But when you’re looking at this huge spectrum of material I’ve got to deal with, you’d spend the rest of your life trying to invert those stereotypes.

Blanton: When you’re writing about Texas history, there are certain personalities that not only can you not avoid, you can’t help but have tremendous affection for them. Sam Houston is one such person. But I found it very admirable that you seem to go out of your way to look for evenhanded, fair things to say about people that might be regarded typically as villains in Texas history, like Santa Anna. Was that a particular aim for you?

Harrigan: Yeah. I just don’t like the castigation of people by modern readers or modern historians, because we weren’t there. I’m sure that if I had grown up in Texas in the 1850s, I wouldn’t have enlightened views about slavery at all. I wouldn’t have been that person who recognized how terrible slavery was. Just like today, I wish I were a vegan, because when it comes to animal rights, I should put my money where my mouth is, but I’m not. I’m not that evolved. So I just don’t want to have too much judgment of people.

And so, on the one hand in Texas history, the eternal villain is Santa Anna, as you said. On the other hand, there is the villain that the revisionists are always happy to attack, which is somebody like Mirabeau Lamar, who was a much more interesting character than the caricature of him, even though he was probably a bad guy. But if I had lived in Texas in the late 1830s, I probably would have been impressed by this guy, just as I would have been impressed by Houston.

Blanton: I was particularly surprised by your gentleness with Mirabeau Lamar, but I wonder‚ do you think Lamar seems so unimpressive today just because he was in Sam Houston’s shadow? Sam Houston is such a bright bulb that all the other bulbs around him seem dimmer and duller by comparison.

Harrigan: Yeah, I think that there are people who take up a whole lot of room in Texas history, and legitimately so. And I think Houston was such a fascinating character on every level, and visionary and tiresome and grandiose and farseeing and all that kind of stuff. There is still a kind of hagiographic attitude toward Houston in Texas, but he owned slaves. He wanted to essentially re-invade Mexico at one point, make it a Texas protectorate. By the standards of our day, he wasn’t all that much more enlightened than Mirabeau Lamar, even though certainly much more toward Native Americans. But they’re just two of the really interesting characters that make Texas what it is.

Blanton: There are a few personalities, though, who you clearly did not like, such as Edwin Walker, the right-wing Dallasite who protested against integration.

Harrigan: Yeah, General Walker, Bruce Alger [a strongly conservative Dallas congressman], all those guys. But again, they were embedded in their time, and your responsibility as an historian, I think, is to understand that time. And I made a point of saying in the book that when I was a kid in Abilene in the 1950s, during the Red Scare, I was scared. I thought the Soviets were going to blow us off the face of the earth, and that fear was real. And so I don’t necessarily think that the people who were infected by that were necessarily bad people. Were the Mink Coat Mob [a group of well-heeled female anti-LBJ protestors organized by Alger] the sort of people who would be voting for Trump today? Maybe not. Who knows? They haven’t had the experiences and the political and social context that we’ve had.

Salamon: You seem to have a particular distaste for H. L. Hunt, and I’m just curious if that’s because your life overlapped with his, so his life isn’t just something you read about in books, it’s something you remember.

Harrigan: Yeah, but again, I don’t have a distaste for people like that. I just have this exuberant curiosity. They’re characters to me, and H. L. Hunt was a real character. You can’t not write about him and not have a little fun with him.

Blanton: I think the true distaste that you exhibit, one of the greatest distastes that you exhibit in this entire book, is for Hunt’s dystopian novel, Alpaca. It kept coming up. It’s like it couldn’t be contained within the chapters that Hunt was in. It shows up in the Woodrow Wilson chapter as well.

Harrigan: I couldn’t get away from Alpaca. But I didn’t hate it. I was thrilled by it. There’s nothing more fascinating than a really bad novel.

Blanton: I need to read Alpaca now.

Harrigan: I have a copy over here, if you want to borrow it.

Blanton: I get the sense that for you, hypocrisy and meanness, especially outright meanness, are the things that would push you to a more negative portrayal of someone.

Harrigan: There are things you just can’t ignore, like the lynching of [the African American] Henry Smith in Paris, Texas, in 1893. There are a lot of evil acts that took place in Texas, but that has got to be at the top of my list. But when I think about this utterly barbaric and officially sanctioned torture and murder of this guy who was never convicted or even tried for the murder of the little girl he was accused of killing, I also think about my family. I recently I went to Ennis, Texas, which is a little over a hundred miles from Paris. My grandmother was born in Ennis, and my great-grandparents are buried there, and I went to the library and went through all the grave records to try to find their graves. During a rainstorm, my wife and I went to the cemetery and searched all over and finally found these two headstones for my great-grandparents. They lived during the time of the Henry Smith lynching, and people from all over that part of Texas—10,000 of them—converged to watch this man be tortured and burned alive, and I just couldn’t help but wonder, were my great-grandparents there? And it made me really wonder, would I have been there? And it made me wonder, again, what is evil? How do we calculate that within the context of a human lifetime?

Blanton: Is writing history different from writing fiction in terms of dealing with evil?

Harrigan: I think in both, you don’t want it to be a black and white situation. There’s no more black and white situation in Texas history than the lynching of Henry Smith but even so, there are uncomfortable truths you have to face about your ancestors and yourself. And I think the first duty of a novelist, and probably the first duty of an historian, is not to make irrevocable snap judgments about human nature, because human nature is very complex.

Blanton: At several points, the book deals with current events, particularly in the last several chapters. One thing that really grabbed me was your description of the Charles Whitman shootings at the University of Texas, and contextualizing those murders with the kind of gun violence that we have today. Given that earlier chapters talked about Bonnie and Clyde, John Wesley Hardin, do you think that’s a through line in Texas history, that such violence is something that’s characteristic?

Harrigan: I think the thing about Texas is that it’s always more so than other places because there’s more of it. It was for many years the largest state in the country. There’s vast potential for conflict in terms of our border with Mexico. The Indian wars in the 1870s were really the last gasp of Indian resistance, and then of course there’s the Civil War, and so we got a big dose of everything. I wouldn’t want to proclaim that Texans are more violent than other people. I think given the circumstances that Texans have found themselves in, the conflicts that have arisen, they are as violent as history has demonstrated. But I don’t think they’re a unique species of human being.

Blanton: Immigration comes up, perhaps because of the salience of the issue today. Immigration comes up at several points in the last chapter or two, and I was wondering: you refer at one point to the “old suspicion” in terms of explaining attitudes about immigration today. Do you think it’s that historically rooted, or do you think that maybe it’s a mix of other kinds of things?

Harrigan: I think it’s certainly a mix of lots of things, but certainly historically rooted. For one thing, it has its roots in Mexican suspicion of American immigration, and there is the long-gestating mutual distrust between these two nations and these kinds of people. But I think when you look at the violence that occurred during the Mexican Revolution and the border, and then the savagery that took place and the suspicion on both sides, I think it’s really deeply connected. How could it not be? Texas shares this border with Mexico that has always been a conflict zone, as much today as it has always been, maybe even more so. Well, probably not more so, because there aren’t border incursions and battles and stuff going on, but there is a climate for that for sure.

Blanton: Final question: Who do you want to read this book?

Harrigan: I don’t try to categorize. I know there’s the gung-ho Texan readership for whom this book might be a bit of a challenge in places, because there’s some holes punched in the Texas myth. But by and large, I hope that any curious, open-minded person who still reads books would enjoy this one.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Stephen Harrigan will be a featured speaker at EDGE: The Texas Monthly Festival in Dallas November 8-10. For tickets, visit edge.texasmonthly.com.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Books

- Stephen Harrigan