Other than a few framed photos of family and friends who had passed away over the years, there wasn’t much in the way of decorations when my family set up our first Día de los Muertos altar. Later came the banner of papel picado, and the year after that tiny sugar skulls. But no matter how our family altar has changed, it always begins with the same centerpiece—a grapefruit—that takes us back to a faraway memory of how it all began.

It’s 1938 and my father is a young man. He lives in Donna, just a few miles north of the Rio Grande, where he works at a packing shed. One afternoon, he’s loading crates of grapefruit onto the back of a truck when he spots a group of high school girls walking by. He tries to make eye contact with one of them and has no luck. Then he sees a little boy playing near the packing shed and has an idea. He tosses the boy a grapefruit and tells him to run over and give it to the girl in the gray gingham skirt. “Tell her there’s someone who wants to meet her,” he says. “Ándale.” The little boy delivers the gift, and this is how my parents become my parents and why every year a Ruby Red grapefruit sits on the altar.

We didn’t celebrate Día de los Muertos as a family when I was growing up. All I knew when I set up my first altar seven years ago was that it honored the memories of the dead. But I didn’t know that the holiday dates back to Aztec times or that what I sometimes call an altar is actually known as an ofrenda, and that offering food and drinks, along with photos and mementos, is part of a ritual meant to welcome back the souls of the departed every year in early November.

The truth is, I didn’t start celebrating it for cultural reasons; I began the tradition so my two kids would remember the people they had little to no memory of. My son, Adrian, was born three months before my father died, and my daughter, Elena, was entering kindergarten when my mother passed away. I wanted them to know who my parents were and where they were born. Most importantly, I wanted them to understand what mattered to my parents: whom they loved and how they died.

Then, earlier this year the pandemic hit South Texas and some of the people my parents loved were not spared. This year’s ofrenda, we realized, would include not only our distant past but also the very sorrow that we’re living through now.

I was born a couple of months after my parents celebrated their twenty-fifth wedding anniversary. By that point, they weren’t going out so often, but when they did, it was either to a dance or to a funeral. In Brownsville, in the seventies, Saturday nights meant dances at the Civic Center or the Friendship Garden. If they went to a funeral or rosary during the week, it was at Treviño, Garza, Delta, or Darling-Mouser funeral home. Not that they had that many relatives and good friends who were dying off. It might be a lady from church they knew only from saying hello to her after Mass every Sunday. It might be the husband of the woman my mom bought her tamales from at Christmas, or the sister of a man my parents used to have coffee with at the Whataburger on Boca Chica Boulevard, or the man at the end of our street who had repaired my father’s lawn mower a few summers back.

After a while, I gave up asking them why they had to go to another rosary, why they couldn’t just skip this one. I’d always get the same answer: “para cumplir,” which essentially meant “to do our part.” That, or “para acompañar,” to be with the family. It didn’t matter if the grieving wife or husband or in-law even knew who my parents were or how they knew the deceased. They weren’t going there to be seen or recognized. They showed up because that’s just what they did.

If it was a family friend who died, I’d have to tag along with my parents at least to the rosary. But if it was one of their friends I’d never met and shaken hands with—something my father put a lot of stock in—then it was okay for me to stay home. Once, though, when I was ten, my dad took me to a rosary for the father of a friend of mine from the Boys Club. The man had been killed in a bus wreck coming back from Ciudad Victoria, something that I still remember any time I’m traveling in Mexico and pass another roadside shrine.

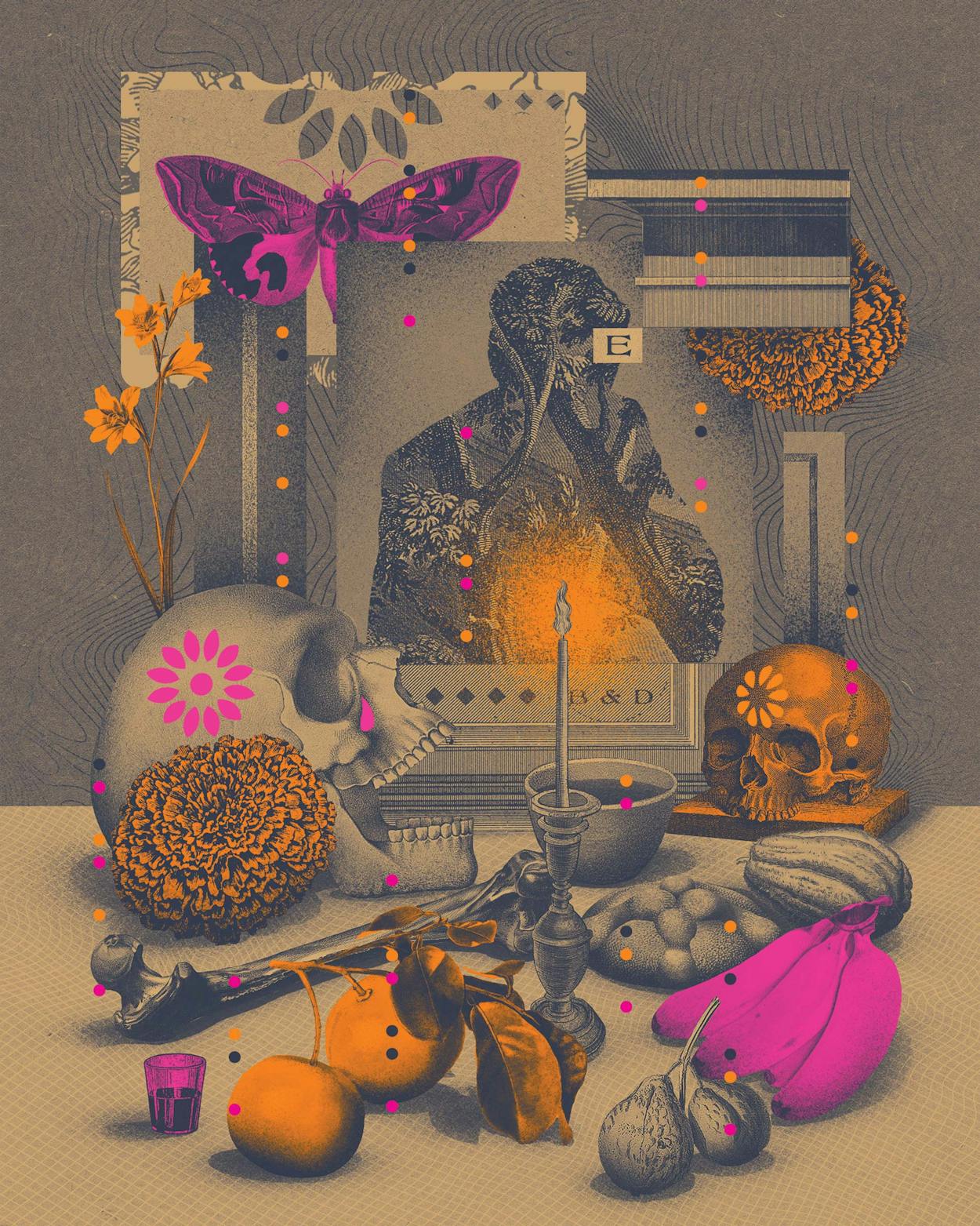

Heart of Marigold

These flowers often adorn ofrendas, as their petals are believed to lead the souls of the dead back to the altars.

Family was different. Losing someone close to us also meant being with those we hadn’t seen and held in years. While these funerals were sad occasions, a part of me looked forward to having my uncles and aunts and cousins pour in from Chicago and Fresno and Grand Rapids. Then, after the burial, we would gather in someone’s kitchen or backyard to hear the stories we hadn’t heard since the last time we were together. My tío Nico would tell one about the afternoon he was in his backyard, in Houston, working under his car—a buttercup-yellow 1969 Chevrolet Bel Air—trying to loosen a bolt. Then, just as he turned onto his side, the car suddenly wobbled off its blocks and fell on him. It sounds awful, but not when he reenacted the whole scene, including the way he yelled for help—BELIA, AYÚDAME . . . AYÚDAME!!!—and then told us how he was saved, miraculously—no other way to put it—when my tía Belia and my cousins Hilda and Rosy grabbed hold of the bumper and raised the car just enough for him to scoot out.

Then there was the one about the blowout my tío Héctor had in the middle of the King Ranch—a good twenty miles from the nearest service station—only to discover his spare tire was flat. He and my tía Nena and my tía Lilia hitched a ride with an eighteen-wheeler, but there was room only for him in the passenger seat, so my tías had to climb behind the seats and lie down in the sleeper cab, staring up at themselves in the trucker’s mirrored ceiling. Or the story about my father driving a taxi one night in downtown Brownsville, around Market Square, circa 1944, when a guy backed out of one of the cantinas swinging a bar stool at two other men. When my dad got closer, he realized the guy with the bar stool was my mother’s younger brother, Óscar (my tocayo!), so he slowed down enough to reach over and push open the passenger door so his cuñado could hop in. Those kind of stories.

After seeing my parents attend so many rosaries and funerals, I guess it shouldn’t have surprised me years later when my father, already in his eighties and a full decade after retiring, took a part-time job at a funeral home. He had spent most of his life laboring under the South Texas sun as a farmworker, a delivery man, a fireman, and then a cop, and a tick inspector for the USDA, which he did for 33 years, much of that time riding horseback across long stretches of the Rio Grande to make sure livestock weren’t crossing over from Mexico and spreading cattle fever in this country (this explains why his belt buckle of a quarter horse also has a spot on our ofrenda).

As an attendant at the Treviño Funeral Home, he was expected to answer the phone, greet and direct people to one of the two chapels, encourage them to sign the guest book, and give directions to guests coming in from out of town. If someone called in sick, he might need to assist one of the funeral directors at the church and burial. He loved getting dressed up for work in one of his dark suits, then slipping on a tie from the half dozen he kept hanging on a belt rack. He loved wearing real lace-up shoes, not the ones with the Velcro straps my mother had bought him when he retired and stopped wearing his work boots. He loved being the first one to work and the last one to leave, and he especially loved helping people whose families he had known for ages.

My father died in 2007, but I wonder how he would have reacted to seeing all the parents and grandparents, tías and tíos, and primas and primos who have fallen to COVID-19 in the Rio Grande Valley—especially in Hidalgo County, which is more than 90 percent Latino and became the epicenter of the crisis in Texas this summer: The county represents only 3 percent of Texas’s population but accounted for 21 percent of its coronavirus deaths then. It was here in late July that we lost my father’s favorite nephew—my cousin, A. C. “Beto” Jaime. A couple of days later, his wife of 63 years, Dora, also passed away from the coronavirus.

After a lifetime of civic involvement, including his time as the first Mexican American mayor of Pharr, from 1972 to 1978, Beto was well-known in the area. But due to social distancing mandates, his and Dora’s combined funeral service was limited to immediate family, all of them wearing masks and discouraged from hugging and crying on each other’s shoulders. I can’t imagine how my father would have made sense of the restrictions that prevented family members from being with Beto inside the ICU, holding his hand as he took his last breath. What would my father say if I told him that we could only watch the livestream of the funeral, on my laptop, the same one I’m using to type these words now? If he had watched a pair of attendants wheel the two caskets up the aisle and place them near the altar, side by side, would he have felt a terrible sob catch in his throat, as it did in mine?

Of the many ways this pandemic has felt so unfair, it sometimes feels as if the cruelest part has been how it has deprived us of this ritual of grieving our losses together. Growing up along the border, we were all reminded of how precarious life could be, but also of how we would always be there for one another. We understood that, no matter what, those of us left behind wouldn’t carry this loss by ourselves.

Accepting these recent deaths in isolation has been even more difficult since we’re a family of touchy-feely people. We hug, we kiss, we cry, we hug some more. No one cries as long and passionately as my tía Minerva, who, six years ago at my mother’s burial, had to be held back from clinging to the casket as it was lowered into the ground. I still remember the abrazo Beto gave me at my father’s rosary, patting me on the back as he squeezed me a little tighter, reminding me over and over that I wasn’t going through this alone.

Many people’s ofrendas this fall will no doubt memorialize family members who have died from the coronavirus. So now, alongside my father’s belt buckle and the grapefruit, I’ll need to add a photo of Beto and Dora dancing, something they loved to do at every wedding and family reunion. I can see that irrepressible smile on Beto’s face as he spins Dora one way and then right back into his arms, like the song might never end.

Since Beto and Dora’s burial itself wasn’t livestreamed, I had to hear about it from their eldest son, Bert, who works as a chaplain at a nearby hospital and served as an acolyte during the Mass. Bert had planned to deliver the final prayers at his parents’ burial, and when the moment came, he walked toward the gravesite, past his five siblings and their families and the musician they had hired to serenade their parents.

They were all waiting for Bert to speak, but as soon as he opened his mouth, he choked up, unable to get the words out. He thought of how his father had died, and then his mother, within 48 hours of each other. He thought of the two weeks that had passed before the memorial service could take place—the funeral home’s schedule had been overwhelmed by the number of COVID-19 deaths in the area. He thought of how accepting his parents’ death felt like a test of his faith in God’s will, and he wondered if he would even be able to make it through the final prayer. And then he felt someone lay a hand on his left shoulder, and then another hand rest on his right shoulder. He turned to see his youngest brother, Kevin, and his own son, Andres, standing behind him, steadying him. It was all he really needed to make it the rest of the way.

This article originally appeared in the November 2020 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Beyond the Grave.” Subscribe today.