This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

“He squares his jaw. He fixes them with a glaring eye. He stabs a convicting finger across an open Bible and barks, ‘You’re a sinner!’ and their hearts are pierced.

“His features soften. He looks on them with compassion. He says quietly, ‘Jesus loves you.’ And they believe. And they stream forward by the hundreds to begin new lives in Christ.

“Who is this man?”

—From a James Robison Evangelistic Association brochure.

Johnny Cash calls him a man of destiny. W. A. Criswell, pastor of the First Baptist Church in Dallas, describes him as “a new star in the galaxy of God’s flaming, shining lights who point men to Christ.” Jerry Falwell proclaims him to be “the prophet of God for this day.” And the late H. L. Hunt called him “the most effective communicator I have ever heard.”

Almost twenty years ago James Robison set himself a course that many felt would eventually enable him to fill the gap left in the hearts, minds, and stadiums of America when Billy Graham passed from the scene. His blunt, sometimes crude forthrightness probably makes that expectation unrealistic, but this same quality has helped propel him to a position of public leadership second only to Falwell’s in what has come to be called the Evangelical New Right.

Using syndicated television programs, computerized mailing lists, and impressive rhetorical skills to play upon the faith, fear, longing, and hope of several million Bible-believing Christians upset with the decline of America’s strength and spirit, Robison and Falwell and a host of their preaching brethren have set about to reconstitute the power and the glory of this one nation under God. Reaction to their efforts has ranged from triumphal shouts to gnashing of teeth, but no one has suggested that they have not made a difference. A man of great gifts and contradictory parts, Robison is easy to love, easy to hate, easy to admire, easy to fear, and impossible to ignore.

James—never Jim—broke into the mass media at the age of three weeks, when his deserted and destitute 41-year-old mother, who had tried unsuccessfully to have him aborted, placed an ad in the Houston Chronicle offering the infant to anyone who would take care of him. A Baptist preacher and his wife answered the ad and kept the boy at their home in Pasadena until he was five, at which time his mother reclaimed him and hitchhiked to Austin and ten years of transient existence in cheap apartments and boardinghouses.

Though he never got into serious trouble, Robison spoke of these days as a time of singular wickedness and squalor. “When I was a kid,” he recalled, “I planned rapes and plotted crimes. I considered everything but murder. I was mean. I’m talking about sadistic! Cruel! I killed animals. (I don’t know if you want to put that in there, but it’s all right. If God can use it, fine.) Deliberately, I killed a little dog—just threw it on the floor until it died. I killed a cat. Put it in a fire. My mother couldn’t get me to admit it. God, I was bad! I was filthy! It was because of conditions in my home. I didn’t have a daddy. It’s right there on my birth certificate—‘illegitimate.’ ”

James’s father, whom he describes as an alcoholic, moved back in when the boy was fifteen, and the resulting turmoil forced him to seek refuge with his foster parents in Pasadena. While living with them, James was converted, an event he retells with the relief of a man who has just escaped from a galloping terror. Not only did salvation provide escape from his sinful past, it offered a kind of familial experience he had never known.

“I only knew one Scripture in the Bible,” he said, “and I got that out of a Classics Comics that I read on the shelf of the grocery store when I was a sack boy. I was doing a book report and I always got them out of the Classics Comics. There was a picture in there where Jesus had just been baptized by John. He came up out of the water and the Holy Spirit descended on him in the form of a dove and a voice from heaven said, ‘This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased.’ All my life I wanted my mother to say, ‘Son, I am so pleased with you.’ All my life I longed for a father. You don’t know how insecure I am. I never had a daddy say, ‘Come on, son, you can do it.’ I always believed I couldn’t. When I walked down that aisle to get saved that night, the only thought I had was ‘Tonight someone is pleased with me. I am pleasing God. God is happy. I am making God happy.’ ”

Life in a Baptist preacher’s home exposed Robison to a steady stream of Christian influences and led to his decision, at age eighteen, to become an evangelist. He began preaching soon afterward and continued while attending East Texas Baptist College and San Jacinto Junior College. At the end of the fall term in 1963 he elected to drop out of school, skip seminary, and launch a full-time evangelistic ministry. “I was so busy doing what God called me to do,” he explained, “and it was so apparent that His blessing and anointing were on me that it would have seemed foolish to go to seminary. It would be like an old boy that was making twenty million dollars manufacturing something deciding to go to school to get an engineering degree. What are they going to teach him? I don’t believe it would hinder an evangelist to get an education, but it might. It might take away something God is trying to say.”

In the first year of his evangelistic work Robison held 25 revivals in 4 states. Reports of his prowess were so enthusiastic that the following year brought nearly 1000 invitations from 27 states. Not all of the offers during these early years were to preach the gospel. According to Robison, H. L. Hunt was sufficiently impressed with his persuasive skills that he offered to underwrite a step-by-step plan that would lead to a political career. James, then only 23, declined the opportunity, but apparently without alienating the family, since Nelson Bunker Hunt has been known to show up at events sponsored by his ministry.

In 1965 Robison established the James Robison Evangelistic Association (JREA), a move that provided him with an institutional base independent of the Southern Baptist Convention, though he has maintained close ties with the denomination. He continued an active crusade ministry throughout the rest of the sixties and in 1970 began a television ministry with a thirty-minute program that was aired on only four stations.

As the demands and results of television increased, Robison gradually cut down on the number of revivals, but the wider exposure afforded by television combined with his youthfulness, his scandal-free reputation, and his bombastic fundamentalism to make him a favorite in fundamentalist circles, so that even with his reduced schedule of revivals it was generally agreed that only Billy Graham spoke to more people in person each year throughout most of the decade. James recognized he was well behind Graham in popular appeal but speculated that, because he preached a stronger, more demanding message, his converts and supporters would probably be more loyal to him in a time of trial than would Billy’s.

Robison, now 38, is perfect for the role he plays. He is six three and 210 firm pounds, with thick, black, wavy hair, piercing eyes, and a face like a handsome high school athlete’s. His style is rough-and-tumble, hardheaded, aggressive, and frequently abrasive. He dresses in conservative business suits and professes to dislike the celebrity image that comes with the television ministry, but he obviously relishes and cultivates his reputation as God’s Angry Man, a bold prophet who says what he thinks, regardless of the consequences. “I preach it straight!” he says. “I just—bang—get up and pull the trigger.” He often warns, “Don’t ask me what I think, because I’ll tell you.”

And he will tell you, with smart-aleck sarcasm and withering screams and contemptuous mimicry, his swarthy face dripping with sweat and twisted into a snarl. Then, while you flinch at the hostility in his jut-chinned bluster, he will disarm you with his candor and sense of humor and charm you with gentle, touching sentiment. Robison, however, does not aspire to become a smiling, smarmy, cooler-than-thou electronic pastor, assuring viewers that they are loved and that something good is going to happen to them through “possibility thinking,” praise the Lord and pass the absolution.

“ ‘When I was a kid,’ Robison remembers, ‘I planned rapes and plotted crimes. I was mean. I’m talking about sadistic. Cruel. I killed little animals.’ ”

On the contrary, he likens himself to Jonah, sent to cry out against the wickedness of Nineveh, and to Jeremiah, who was directed “to root out, to pull down, to destroy, to build, and to plant.” He explains that “God has given me the role of pulling down and destroying anything that is raised above God or in place of God or that limits God’s work in the nation, the Church, or the world. That means the idolatry of excessive government or the idolatry of appetites and entertainment and pleasure, or anything else that gets between an individual and God.”

The prophet’s role, he says, is “one of the most misunderstood, misrepresented, and resented roles an individual could ever have,” and he claims it breaks his heart when people construe his message of repentance and judgment as harsh and lacking love and compassion. “When you are preaching judgment,” he insists, “you are actually preaching grace, because turning from the sin that brings judgment automatically brings forgiveness and grace and the salvation of God.” But even if people never understand, he vows not to abandon his course: “I must do it. I am compelled to do it. I am driven to do it. . . . Isaiah asked God, ‘How long do I cry out? How long do I preach?’ and the Lord said, ‘Until the entire land is in waste, until there is no man standing.’ I personally hope that I preach it until everyone repents as they did in Nineveh and we see the blessings of God. But if it doesn’t happen, then I’ll be preaching it until the entire land is in waste.”

By the beginning of this year Robison had spoken to an estimated 10 million people in person and claimed to have won nearly half a million people to Christ in more than five hundred crusades and rallies throughout America. His weekly syndicated television program, James Robison, a Man With a Message, is broadcast over approximately one hundred stations in 28 states. His magazine, Life’s Answer, is the best of any published by the major television evangelists, offering readers news of the ministry, thoughtful consideration of major social and personal problems, and occasional pieces by spokesmen for opposing viewpoints.

The JREA, which is headquartered in the Fort Worth suburb of Hurst, employs 150 full-time staff members, and Robison’s budget has grown from $2 million in 1977 to $11 million in 1980, with $14 million projected for 1981. There is no evidence that Robison is interested in building a personal fortune. He draws a salary of approximately $50,000 a year. He and his petite, attractive wife, Betty, and their three children—Rhonda, sixteen; Randy, eleven; and Robin, seven—live in a comfortable but not extravagant house in the Fort Worth bedroom community of Colleyville.

Like most of the media preachers, James works extremely hard, with little time for hobbies or recreation, though he does coach YMCA football and play an occasional round of golf. There are grizzly bear and mountain lion heads mounted on the walls of his home, and a fact sheet distributed by his public relations office notes that he “has fished in all southern states, Mexico and Alaska, having caught trout, bass, and sailfish.”

The Prime Time Mission

As the seventies drew to a close Robison began to consider various ways of expanding his ministry. Aware that the audience for his weekly program was small—less than 500,000, according to the major ratings services—and composed largely of people who were already church members, he began to experiment with prime time weeknight television specials. In the summer of 1979 he aired three documentary-style productions that contrasted sharply with the “talking heads” format of his weekly program and focused on America’s moral and spiritual problems. Though he decries the ubiquity of sex and violence on television, one of the specials included footage of prostitutes, strippers, nude children in porn movies, concentration camp Jews, assassinations, war, and the infamous on-camera execution of a Viet Cong prisoner. Another program was a powerful treatment of child abuse.

The response astounded even Robison, swamping what was described as the largest WATS line operation in the country—more than 225 lines—with 35,000 calls. A similar reaction occurred with a 1980 special, Wake Up America, We’re All Hostages, which featured comments by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and appearances by former Treasury Secretary William Simon, Senator Jesse Helms, Congressman Philip Crane, Campus Crusade for Christ director Bill Bright, Jerry Falwell, Christian Broadcasting Network head Pat Robertson, and several retired military leaders, all of whom made dark predictions about America’s future.

In addition to the specials, Robison also began producing films of his crusade services. Those programs were similar in format to the Billy Graham television specials but designed for prime time use in cities where evangelical churches, in cooperation with the JREA, mount full-scale crusade operations, with the preaching done by television instead of in a stadium or coliseum.

James frequently says things like “God revealed to me’’ or “God told me to” launch some new project, but he can’t explain precisely what he means by such statements. “God makes impressions on my mind and my spirit that would be as difficult to describe as explaining how you know in your heart that you are in love,” he says. “Many people go wrong when they say they hear from God but what they hear contradicts the Word of God. When that happens it didn’t come from God. I never assume I have heard something from God that cannot be confirmed in Scripture. If I say, ‘God gave me a mission,’ there must be a similar mission in Scripture. There’s nowhere in Scripture that God told me to preach on television, but God told me to preach to every creature, and television is the best way of getting there.”

Robison’s identification of his impulses with the will of God has given him the confidence to draw bold, clear lines between truth and error. He describes himself as “a staunch archconservative” who both “expects and desires” the churches that support his crusades to subscribe to an uncompromising statement of the major pillars of evangelical belief. “I don’t recommend that people go to the church of their choice,” he observes. “I recommend they go to a church of God’s choice—a church that preaches the Word, believes the basic doctrines, and practices evangelism. Our ministry will ultimately hurt liberal churches and churches that don’t believe in anything. I wish it would destroy them, because if they don’t believe anything, we don’t have any need for them.”

Some Southern Baptists, such as Dr. Kenneth Chafin, pastor of Houston’s South Main Baptist Church, fear Robison may do serious harm to his own denomination, particularly with his strident attack on seminary professors who take a soft line on the inspiration and infallibility of the Scriptures. In an address to the Pastors’ Conference just before the 1979 Southern Baptist Convention meeting in Houston, James compared such men to rattlesnakes and cancers and urged the election of a convention president “totally dedicated to the removal from this denomination of any teacher, any educator, who does not believe the Bible to be the infallible, inspired, inerrant Word of the living God.”

Unslowed by the habit of scholarly investigation and unencumbered by the weight of evidence, he also urged that doubts about such matters as Moses’ authorship of the Pentateuch (the first five books of the Bible), the virgin birth, the Second Coming, and heaven and hell be laid aside: “Let’s quit asking all these silly questions. Forget these questions and preach the facts of God’s truth. All of these things are true. We ought to preach the Bible as it is to men as they are.” The elections in two successive terms of literalist presidents Adrian Rogers and Bailey Smith and a controversial attempt to smoke liberals out of Southern Baptist colleges and seminaries have made Robison unpopular with the moderate elements within his denomination but have also, if anything, boosted his stock with those who see him as one of the last holdouts against heresy.

“Robison says what he thinks with smart-aleck sarcasm, withering screams, and contemptuous mimicry, his swarthy face twisted into an angry snarl.”

Smiting Lust and Women’s Lib

As one might expect from a self-styled dogmatic fundamentalist, Robison not only preaches “pure doctrine” but also rails against sin, which he does not hesitate to call by its first name. His prime target, selected at least in part because he rather obviously understands its powerful allure, is sex. He describes the glories of marital sex with such feeling, and summons images of legs, hips, waists, and breasts so effectively, that it is difficult for a creative person in good health not to become distracted.

In a talk to a group of young people, for example, he spoke in excited, almost lurid tones of the response a girl’s body can stir in a young man’s loins: “Man, when you see a girl’s leg or breast, it’s supposed to bother you. If you can look at her legs and her body and it doesn’t bother you, you are a pure queer. . . . Girls, if your boyfriend walks out of here tonight and looks over at your legs just shining in the breeze and says, ‘Your legs don’t bother me,’ you can put it down—you’ve either got hideous legs or he’s a pervert.”

In such talks James typically places all the responsibility for chastity on the woman and admits he told his wife during their courtship that there would be times when he would be weak and would need help in keeping his passion under control. Sex before marriage, he warns, develops sensual drives that can never be satisfied and may cause a man to behave like an animal. “Some girls become that way, too,” he admits, “but most of them don’t. When they do, it’s the most awful thing that can happen to humanity.” Robison’s supporters obviously take his views seriously; his book Sex Is Not Love has sold more than half a million copies.

Robison is even more vociferous in his attacks on homosexuality, which he characterizes as “almost too repulsive to imagine . . . one of the vilest sins known to man.” In 1977 his televised denunciation of homosexuals and the “queer ministry” of the Metropolitan Community Church led WFAA-TV in Dallas to grant equal time for rebuttal by a minister from a Fort Worth branch of that church. To Robison, the idea of a church that caters to homosexuals is absurd. “It is totally unscriptural,” he says. “Being gay is a sin. You can’t have a Mafia church where the members say, ‘We’re Christians but we’re gangsters.’ As far as I’m concerned, a homosexual is in the same class with a rapist, a bank robber, or a murderer. You don’t have to trouble yourself about whether it’s normal to be a homosexual. God didn’t create Adam and Edward. That’s just not the program!”

Robison has no sympathy with the view that homosexuals have little choice in their sexual preference. “Not so! Not so! I had all sorts of opportunities to be a homosexual. My buddies tried to get me to do things like that. I thought about it. I didn’t have a car, I couldn’t date, and I thought, ‘Man, this may be my only out.’ Gays can’t tell me anything I don’t already know about hang-ups and problems. I’ve been there, but when I took Jesus into my life I was transformed, totally transformed. Jesus changed my life and he will change theirs too, no matter what sin they have.”

Robison attacked homosexuals again in a February 1979 broadcast, pointing to the murders of San Francisco mayor George Moscone and city supervisor Harvey Milk as part of God’s judgment on homosexuals, citing an assertion in National Enquirer that homosexuals prey on one another, and quoting a police chief as saying that homosexuals recruit and murder little boys. At this, WFAA-TV decided to cancel Robison’s program altogether, a step that provided the evangelist with an enormous publicity bonanza. Within days he hired attorney Richard “Racehorse” Haynes, who prepared a request for the Federal Communications Commission to review whether WFAA had restricted the evangelist’s First Amendment rights.

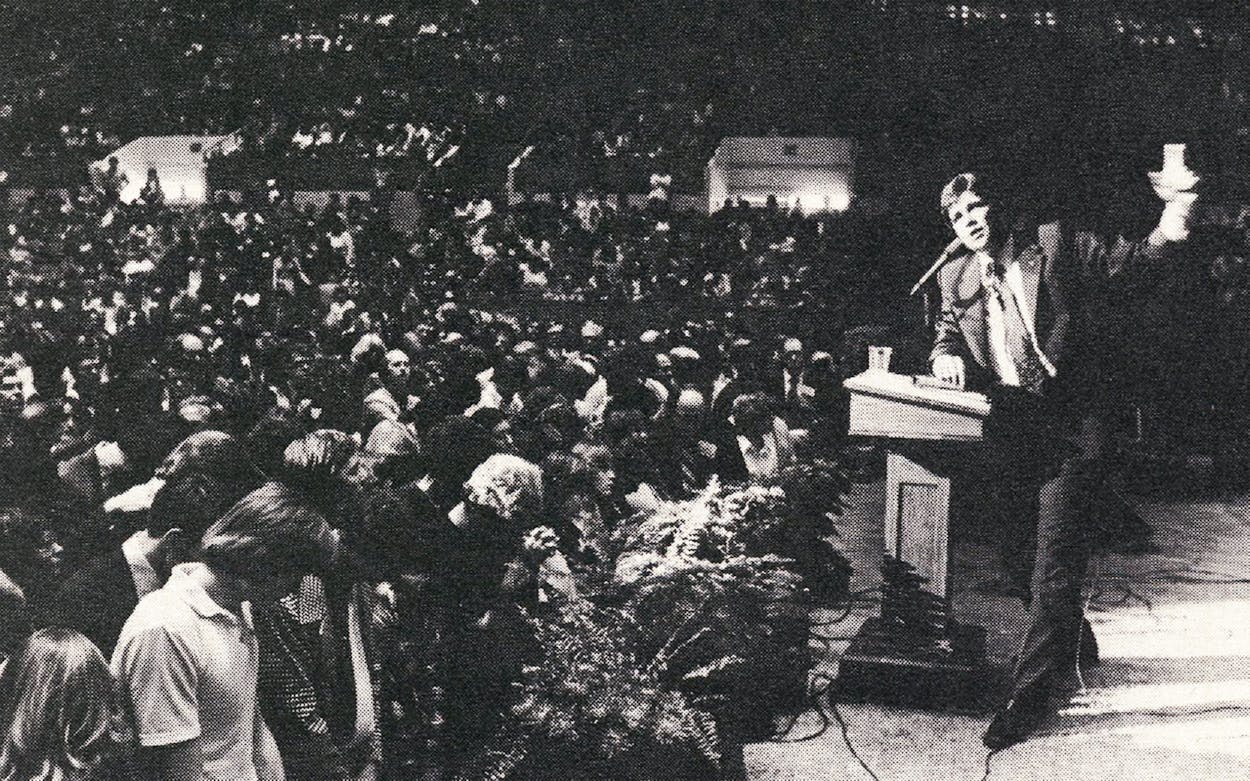

While this was still front-page news, Robison organized a Freedom to Preach rally in Dallas that drew 11,000 supporters to hear Haynes, Jerry Falwell, veteran radio preacher J. Harold Smith, and W. A. Criswell decry the loss of precious freedoms that WFAA’s actions presaged. Robison himself spoke for 45 minutes, delighting the crowd with a bit of showy rhetoric—“It is a shame that America knows more about Mickey Mouse than about Moses . . . more about Charlie’s Angels than about God’s angels . . . more about Shell than hell . . . more about Phillips 66 than about the holy sixty-six books of the Word of God . . . more about Hugh Hefner than about the heavenly heralds.”

When he asked for donations to pay his legal fees he reaped a harvest of $82,000. The FCC and the Supreme Court eventually sidestepped the case, thus affirming the right of a station to make its own decision in such instances. Still, not long after the rally and a visit to the station by Baptist businesswoman and philanthropist Mary C. Crowley and a delegation of what Robison described as “some of the more persuasive ladies in Dallas,” WFAA welcomed the controversial preacher back onto its schedule.

In keeping with his conviction that the “program” for male and female roles has been rather rigidly ordained by God, Robison views the women’s liberation movement as “an immoral, perverted cause” led by “crybabies and rabble-rousers.” “The women’s movement is silly,” he says. “Women have great strengths, but they are strengths to help the man. A woman’s primary purpose in life and marriage is to help her husband succeed, to help him to be all God wants him to be. If a man leads well, a woman is glad to follow.”

When women work outside the home they risk a reduction of their husband’s esteem for them. “The man’s attraction,” Robison has written, “is to a woman, not to a ‘professional person’ and certainly not to a competitor whose success makes him feel inadequate in his God-given role as a provider.” This sense of inadequacy may well extend to the marriage bed, particularly if the woman becomes sexually aggressive: “The masculine partner has traditionally been the initiator of sexual activity. It confuses and annoys men to find women behaving as pursuers rather than the pursued.”

The ERA, Robison warns women, is a cruel hoax that would rob them of their freedom and dignity and subject them to greater discrimination than they have ever known. “Men will refuse to work and refuse to pay child support. Some men are of such a sorry nature that they’d refuse to fight and insist that women go fight.

. . . I’ll fight devils, hell, buzz saws, and perverts on behalf of women, but don’t try to be a man.”

Robison Ascending

Despite his belligerent style, rigid dogmatism, and condemnatory message—or perhaps because of it—James Robison had climbed by the end of the seventies into the lower ranks of the top ten most popular television evangelists. His audience and reputation, however, remained largely regional, concentrated heavily in the South and Southwest, where fundamentalism is still in flower and fiery preaching not only strikes responsive chords but is appreciated as an art form. The emergence of the Evangelical New Right—a conservative coalition of veteran political operatives, evangelical preachers, and several million people who were anxious, frightened, and angry at what they perceived to be the political, economic, moral, and spiritual decay of the nation—catapulted the preacher from Texas into national prominence.

Robison claims that his leap into politics surprised no one more than himself, but that getting kicked off WFAA-TV made him aware of the enormity of the assaults being made on decency and freedom. At that point, he has said, he realized he had to abandon the attitude of “Well, everybody else is being eaten by alligators; I hope they eat me last.”

Robison, like Jerry Falwell, was a neophyte in the political arena, but they both fell in with a group of archconservative war-horses who provided them with organizational know-how and logistic instruction. With the help of conservative ideologue Paul Weyrich, direct-mail expert Richard Viguerie, and veteran organizers Ed McAteer and Howard Phillips, Falwell founded Moral Majority, a group whose name became a generic if inaccurate term for the Evangelical New Right. Robison joined McAteer to organize and lead the Religious Roundtable, whose Council of 56—the same number as the signers of the Declaration of Independence—includes key New Right figures from Congress, the retired military, special-interest and all-purpose conservative groups, and politically oriented television ministries.

Spokesmen for these and other New Right groups, such as Christian Voice and Conservative Caucus, describe themselves as “pro-life, pro-moral, pro-family, and pro-American.” To be pro-life, of course, means to be vehemently opposed to abortion. The pro-moral category includes opposition to pornography, homosexual rights, and moral permissiveness in general. “Pro-family” is an umbrella term for a potpourri of issues that includes reduction of taxes, support of a school prayer amendment, and opposition to the ERA, excessive welfare benefits, forced busing, sex education in the public schools, government funding of divorce or civil rights litigation, and government regulation of schools, homes, or other programs run by religious organizations. Pro-Americans favor a rapid return to military superiority over the communists, oppose attempts to limit rugged free enterprise capitalism, and prefer to stick with proven allies rather than make alliances with enemies who hate our guts and our God.

Most grass-roots movements flourish best when they have a readily identifiable focus. It may be a charismatic leader like Martin Luther King, a dramatic goal like recapturing the Holy Land from Muslim control, or a common enemy like communism, to which all manner of evil and imperfection can be traced. The New Right enjoyed all these advantages. Robison and Falwell had charisma to spare, America desperately needed to be rescued from sin and mismanagement, and somebody somewhere had uncovered the ideological taproot of most of Western civilization’s troubles: secular humanism.

According to Robison and those who speak at events he sponsors, secular humanism rejects the authority of Scripture and promotes the delusion that man can solve his problems without reference to or assistance from God. Though it ostensibly champions the dignity of man, it denies he has a soul or is capable of salvation, and it leads inexorably to his degradation and a level of existence barely superior to that of animals. Its “creed book,” The Humanist Manifesto, favors freedom of sexual choice, equality between men and women, abortion on demand, suicide, euthanasia, and one-world government. It is ultimately responsible for crime, disarmament, declining SAT scores, “values clarification,” and the new math. And it seeks to limit free enterprise, distribute wealth to achieve greater equality, and place controls on the uses of energy and the environment. What is the origin of such consummate evil? “It is spawned by demonism and liberalism,” Robison says, “and that’s a fact!”

James Robison’s most notable contribution to the public image of the New Right was the National Affairs Briefing (NAB), held in Dallas’s Reunion Arena last August 21 and 22. Though the NAB was billed as a nonpartisan affair to which all three presidential candidates were invited, only Ronald Reagan showed up, and it was clear he owned the elephant’s share of the 15,000 potential votes in the arena. He assured the cheering faithful that he turned to Scripture regularly for “fulfillment and guidance” and that “it is an incontrovertible fact that all the complex and horrendous questions confronting us at home and worldwide have their answer in that single book.” And he won their hearts when he remarked, “I know you cannot endorse me, but I endorse you.”

Brigadier General Albion W. Knight, Jr., USA (Ret.) and Major General George J. Keegan, Jr., USAF (also Ret.) stirred some uneasiness with presentations that made it seem a duty of Christians to serve as cheerleaders in the arms race. James Robison sees no problem: “It’s Christian to have a defense. If you slap me, I’ll turn the other cheek, but if you touch my wife, I’ll put you on the floor. There is nothing wrong with defending the right, with standing and giving our lives. Jesus said, ‘Greater love has no man than this, that he lay down his life for his friends.’ He wasn’t talking about committing suicide. He was talking about giving his life in defense. I would give my life to defend my family, and I would meet you at my neighbor’s house if you tried to attack him. I believe that is real Christianity. I believe we are to love our neighbor as we love ourselves. . . . We have a global menace today who terrorizes the entire world. When we refuse to have the defense capability to corral wherever possible and control wherever possible a menace that has threatened the freedom of the entire world, then I believe we have become of all people on earth the most immoral.”

As the November election drew closer, Robison warmed to his new role. He repeatedly described Jimmy Carter as “simply not qualified” to be president and excoriated him for “walking in the counsel of the ungodly.” He claimed Fort Worth congressman Jim Wright “voted wrong ninety-nine per cent of the time” and “sold the country down the river,” and he characterized liberals in Congress as “buzzard brains and vultures.” On the positive side, long before the election he urged his supporters to pray for Ronald Reagan and fantasized that a Reagan victory would bring a smile to God’s face. He chided evangelical Christians for their historic apathy: “Ninety-five per cent of the labor unions vote. Ninety-eight per cent of the liquor interests vote. Feminists vote, radicals vote, gays vote, but only thirty per cent of God-professing people who believe in Jesus—who know Him personally—vote. . . . Why should any politician promise you anything?”

As you have doubtless heard, millions of evangelicals did go to the polls on November 4, and more often than not, the candidates they supported emerged victorious. In addition to Reagan’s romp, the Evangelical New Right helped defeat nine of thirteen senators and about half of the 51 representatives they had targeted. Some spoke of the triumph as “the Validation.” James Robison wrote that by their votes “the overwhelming majority” had indicated they resented, among other things, “having their tax dollars used to support the murder of the unborn and the dissemination of immoral sex information to the young.” He also indicated he was ready with some good advice for the president and left little doubt that he felt he would be called on to deliver it.

As it turns out, the Evangelical New Right may be moral, but it is not a majority. The major rating services indicate that Robison’s average weekly audience is less than half a million people, though a December 5, 1980, fundraising letter claimed, “Over 10 million homes are reached and helped each week by our TV program.” When asked about the discrepancy, James said, incorrectly, that the letter referred to the audience for the prime time specials. He admitted, however, that he had no proof for that claim either.

Pat Robertson’s 700 Club attracts a similar number, and Jerry Falwell’s Old Time Gospel Hour is seen by approximately 1.5 million people each week. Perhaps two to three times that many watch those programs on an occasional basis, constituting a total audience of 5 to 7.5 million, if we assume no overlap between audiences—a highly dubious assumption. Of the other television ministers, none has shown anything like the same concern with political issues, and some, including Billy Graham and Rex Humbard, have been openly critical of their New Right brethren.

When children, shut-ins, the politically apathetic, and die-hard Democrats are subtracted from this 5 to 7.5 million, the number of people who pay close attention to the TV voices of the New Right is substantial but hardly mind-boggling, a conclusion supported by post-election surveys. As a case in point, a poll conducted by U.S. News and World Report determined that 40 per cent of Reagan’s supporters had voted for him out of concern for inflation and the economy; 26 per cent hoped he would balance the budget; 20 per cent were worried about unemployment; 19 per cent were concerned about U.S. prestige around the world. Only 5 per cent indicated that concern with the ERA or abortion had been a factor. Other polls confirm not only that economic factors figured far more heavily in Reagan’s victory than the New Right’s catalog of pet social issues but that, in a showdown, the real majority would vote against the moral majority on such issues as abortion, sex education, the ERA, and handgun legislation. This helps explain why the president selected his Cabinet as if he had never heard of the Evangelical New Right and why George Bush responded to a question about pressure from the preachers with the succinct comment “Hell with them.”

With God and Cullen on His Side

Robison was still flushed with victory in January, at his annual Bible Conference in the Tarrant County Convention Center in Fort Worth. Over a three-day period as many as 11,000 people came to see and hear James and a roster of other high-powered preachers, but the spotlight shone brightest and warmest on the new darlings of the gospel celeb circuit, Karen and Cullen Davis.

As those who read either the gossip columns or the church pages of our state’s newspapers are aware, James Robison performed a notable feat of personal evangelism last spring by converting Cullen and Karen Davis. Since that date, the Fort Worth millionaire and his new wife have spent an enormous amount of time assisting James and his ministry. Robison insists that his interest in Cullen has nothing to do with the fact that he is one of the richest men in the state, and Karen claims the evangelist “has never asked for one thin dime from Cullen Davis.” Robison acknowledges, however, that even without being asked, Cullen has helped him “quite a bit.”

In return, James has given a boost to the Davises’ efforts to become a model Christian family. Karen is codirector of the Christian Women’s National Concerns Conference, a JREA ministry designed to help women understand that obedience to God and true personal fulfillment require wives to be in subjection to their husbands. In public appearances Mrs. Davis often thanks Cullen for giving her permission to be part of the ministry, noting that “fortunately, most of the time the Lord and Cullen are in agreement.”

When Davis addressed the assembly in Fort Worth, he indicated he had cut a ski trip short to come back and talk on “an evil subject—humanism.” He said little that Robison has not written or said many times, but he said it in that flat, cold, passionless voice that has proved so persuasive in the past when he has spoken in public of crime, sex, and moral decay.

Robison’s followers at the conference were no less enthusiastic than he was, applauding energetically at such statements as “On November 4, God gave us grace by removing an administration soaked in humanist, liberal philosophy and theology.” Robison noted, however, that though Reagan is potentially capable of providing the leadership America needs, he is surrounded by “very poor influences” and needs a lot of prayer and support. He also speculated that without a sweeping revival, we would experience nuclear war within less than five years. The prospect, interestingly, did not seem to dismay him, because “wherever it hits, there will be, along with death, a revival within twenty-four hours, and all the humanists are going to start trying to find the God they denied. It is a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the living God.”

Such notions as a God who voted Republican and nuclear war as a tool for winning souls have brought cries of caution and howls of indignation over the political involvement of Robison and Falwell. Groups of humanist scholars obviously deplored what they were doing, and even fellow evangelicals expressed concern. The loudest of the complaints charged that Robison and his cohorts have breached the wall of separation between church and state. But of all the criticisms leveled at the Evangelical New Right, this is the most specious. The Constitution nowhere suggests that religious groups or individuals must refrain from trying to influence the civil government, and even a cursory examination of the fabric of American political life reveals a complex interweaving of bold and subtle religious threads. During the young republic’s fourth presidential election, a Philadelphia newspaper told voters their choice was “Adams, a religious president, or Jefferson, and no God.” (Perhaps because fewer than one fifth of the population were church members, Jefferson won the election.) The National Council of Churches and its member denominations have long been active in seeking political solutions to the problems of racism, hunger, and oppression. The Reverend Martin Luther King led the civil rights movement in the pulpit, community, and language of the church. The point is, James Robison and his colleagues are squarely within their constitutional rights and the historical mainstream. If they are to be criticized fairly, it must be for the spirit and content, not the expression, of these convictions.

The Robison Manifesto

Robison is frequently guilty of sidestepping serious intellectual discourse. I doubt that the accusation will sting James sharply, since he has often expressed skepticism about the fruits of intellectualism, but I still regard it as a serious criticism and am convinced that reason and intellect have, on balance, served the world better than their opposites. I do not mean to imply that a conservative position on most issues cannot be argued in a learned, cogent, persuasive manner. But I am offended by such tactics as the lumping together of homosexuality, divorce, the devaluation of the dollar, and the security of Taiwan as if the relation among them should be obvious to all and the problems with them could be resolved by defeat of the ERA or restoration of school prayer. If James has evidence that homosexuals are willfully wicked scoundrels who molest little boys, let him construct a defensible case and have done with quoting a Bible verse, citing the National Enquirer, and snarling about an International Year of the Pervert. I realize he is a preacher, not a professor, that his task is to persuade, not to prove; but a man of his ability who substitutes “seed picking” and rhetoric for the responsible use of logic and evidence can easily become a destructive demagogue.

My nagging fear that James may not play fair if he gains greater influence and power stems from the fact that he does not always play fair now. The cardinal example of this tendency is his apparent determination to place virtually all the sins of the Western world on the scapegoat of secular humanism. Humanism may imply appreciation for the humanities: literature, history, art, philosophy, religion. It may also refer to a belief in the essential dignity of human beings and in their ability to achieve a fulfilling existence without regard to any supernatural being or power. People who believe this can fairly be called secular humanists.

There can’t be many true secular humanists, since only 3 per cent of all Americans say that they do not believe in God, and only a tiny fraction of those belong to the American Humanist Association or to other organizations that might qualify as denominations of “the religion of secular humanism.” There is a Humanist Manifesto, but you won’t see it on your neighbor’s coffee table or in the book rack at Eckerd’s, and if your library has a copy, I suspect you will find it has not circulated widely. When James characterizes it as a Bible or creed book that guides the thoughts of legions of conspiratorial humanists, he is guilty either of gross ignorance or deliberate dishonesty. In either case, he needs to repent.

The only official, card-carrying humanist I know personally—a gentle, sensitive, highly ethical man—has pointed out that Christians and secular humanists may subscribe to quite similar moral codes and that there is “no necessary connection between being a decent, loving, law-abiding, charitable, and life-affirming person and subscribing to a set of doctrines proclaimed in one part of the world and not another, at one time in history and not another, through this particular set of prophets and not another.”

Humanism has some problems, to be sure. I think its view of the essential goodness of human nature is overly optimistic. I also suspect that over the long run and for most people, ethics and morals take firmer root when planted in the soil of religious tradition. But there is one issue on which I feel far more at home with the humanists than with the fundamentalists, and that is pluralism.

The framers of the Constitution made pluralism the cornerstone of the national charter. “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibit the free exercise thereof,” they said, and “no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or public trust under the United States.” Whatever their beliefs—and the God of Jefferson, Franklin, and Madison bore little resemblance to the God of James Robison—they recognized that freedom and the welfare of the Republic would best be served by leaving questions of religious truth to individual conscience, and that government has a duty to protect citizens against attempts to make any one group’s god the sovereign of the nation, any one group’s truth the truth that all must accept. John Adams, “a religious president,” observed, “It will never be pretended that any person employed in formation of the American government had interviews with the gods, or in any degree were under the inspiration of heaven.”

Robison is reasonably careful to insist on the validity of the pluralist ideal and to urge followers to choose leaders not because they are Christians but because they are competent and adhere to the correct moral principles—as determined by God and set forth in Scripture. But whenever one considers issues over which thoughtful and ethical (even dedicated Christian) men and women disagree and announces that those who have reached a conclusion different from his own are immoral, sinful, and un-Christian, instruments of Satan and enemies of God, one violates the spirit of the Constitution and is guilty of arrogance, self-righteousness, and overweaning pride. These are not only described in the Bible as quite fundamental sins but have led to some of the darkest episodes in human history.

I believe comparisons of James Robison to Hitler or Jim Jones or the Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan are cheap shots, as unfair as some of the labels he applies to those who frighten him. But from the tragic experience of such men, all totally convinced of the correctness of their convictions and the purity of their ideals, he could learn a crucial lesson: certainty corrupts; absolute certainty corrupts powerfully. When James levels his charges and makes his pronouncements and delivers his directives, I would urge him to recall the words of Oliver Cromwell, a man well acquainted with the tensions between noble ideals and the will to power: “I beseech you, in the bowels of Christ, think it possible that you may be mistaken.”

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Fort Worth