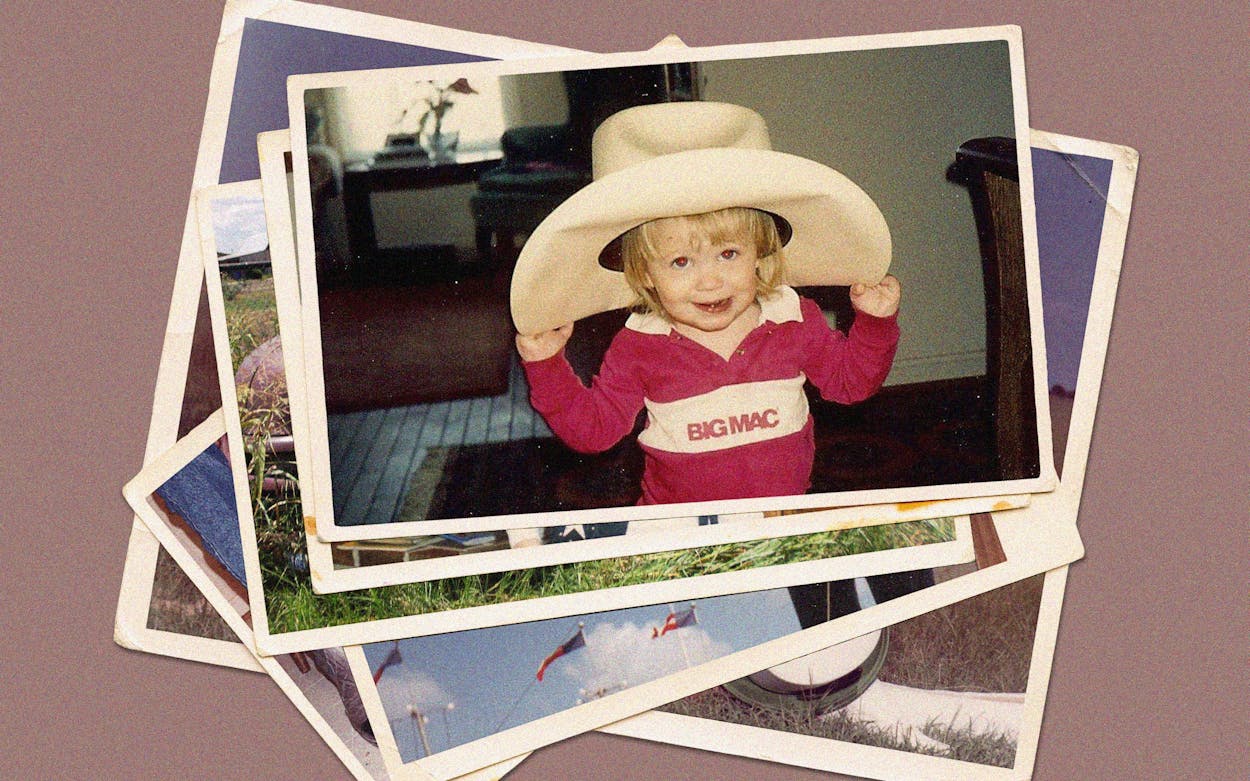

When I was a child, it caused me almost physical pain to know I was not a Texan. Despite the best efforts of my loving parents—my dad, a sixth-generation Texan raised in Dallas, tried to procure a jar of dirt from the homeland to place under my mother’s hospital bed so my birth would technically occur on Texas soil—I was born in Prince William County, Virginia, and spent the majority of my childhood in the suburbs of Atlanta. I grew up wishing with all my childish might that I’d come from this majestic place, because my parents were so proud of their Texanness, a trait that made them exceptional in my eyes.

My mother, who grew up on a working farm, had a worn, Texas-shaped leather keychain, a state-stamped chef’s apron, and bluebonnet notebooks and doodads. Every road trip I took with my family meant hearing my parents sing their a capella rendition of Hawkshaw Hawkins’s ballad “Patanio (The Pride of the Plains)”—technically a song about a horse in New Mexico, yes, but to a kid raised in Southeastern suburbia, it evoked the exotic wonderland of Texas to me.

Texas was the way my mom hooted and cranked up the volume when the songs she’d performed her drill team routines to—as an Emerald Belle at Carroll High in Southlake—played on the radio, the way she’d randomly bust into Tarleton Texan cheers, the way she’d tell me about Purple Poo antics and being excused from class to feed prematurely born calves that she later presented at 4-H Club livestock shows and county fairs. It was listening to hour after hour of Hank the Cowdog audiobooks on long road trips. I got secondhand excitement hearing about the State Fair of Texas, Braum’s ice cream, and my grandpa Delbert’s decree that thou shalt not date dairy farmers. (He didn’t want his daughters contending with the deplorable schedules dairy farmers keep. “Twice a day you milk, without fail, usually at four in the morning and at four in the afternoon,” my mom says. “It’s very hard to get someone to take over for you.”)

That was the same grandfather who wanted to be buried in his cowboy boots. My dad’s mother, Grandmother Loye, was an antiques dealer in Dallas, and preceding her recent death she, too, put in a burial request: “Lay me to rest with my diamonds, in a pink coffin.” That struck me as awfully Texan, in its own way.

Growing up hundreds of miles from the prairies and lakes, the Hill Country, and the Texas desert, all of these tall tales and rhinestone-studded details were exhilarating and larger than life. They gave me a sense of provenance and heritage to be proud of. I felt like I had dual citizenship, the singular experience of being one generation removed from a place.

When I moved to Austin after college, though, everything changed. It was one thing to hear stories, but living here was a whole new dimension, and not always a totally pleasant one. Moving to Austin from Berlin—without a car—was a major adjustment. I hadn’t anticipated just how vast and sprawling a city could be, and how challenging it could be to get from point A to point B without wheels. My lack of mobility quickly came to define my experience in the state: hitchhiking from the suburbs, waiting on buses that never arrived, only having enough cab fare to get to a job interview and then having to walk more than five miles home in the blistering heat. My job options were limited because I couldn’t drive, which meant my housing options quickly dwindled, along with my bank balance. I fell between the cracks for more than a year, unable to receive social services that could have helped, because they came with a requirement to show up for job training that I couldn’t access without a car.

It was a lonely and desperate period of time, and while it was an experience someone could have in many places in the U.S., it happened to me in Texas. I’d meet lackadaisical peers with jobs and cars, and they’d say callous things that made me feel like something was inherently wrong with me. Things like, “Why don’t you just relax and have a good time?” and “It’s so easy to get a job here. Anyone can get hired, even the dumbest, most incompetent person.” This to someone who was rejected from positions at JuiceLand, Bouldin Creek Cafe, and Anthropologie. Maybe if things had gone differently, I would have been the one saying similar things, but the land of possibility I’d idolized in my youth ended up scarring me in many ways. It made me tougher than I’d ever dreamt of being, bordering on grizzled. The lesson I took from my peers’ comments was that Texas’s pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps ethos—that rugged independence I’d grown up admiring—had a dark side. One need only look to the 2021 power grid failure and the persistent refusal to expand Medicaid to see how devastating this mentality can be on a larger scale.

I also came to understand that my parents’ feelings toward Texas might be more nuanced than I’d first thought. I drove through their college campus in Stephenville and saw just what they meant when they described rural living—boots, barn parties in the boonies, and driving out to haunted McDow Hole to tell ghost stories. But there were darker aspects. I came to believe my mom’s disdain for and desire to distance herself from anything remotely hoity-toity was a result of growing up in proximity to the veneered Texas woman archetype. My father’s search for purpose and quest to prove himself through rank and accomplishments came from all the tales, true and tall, about being a winner, how everything’s bigger in Texas.

In 2015, after nearly two years of struggle, I’d finally landed a coveted salaried job in Austin and my parents had bought me a serviceable jalopy, but I received a job offer in New York City during my second day of training. A guy from Corpus Christi had just broken my heart, and I felt a strong urge to start over again somewhere new. I was following the money and opportunity, but NYC was also a place I’d always dreamt of living someday. I bought the 1989 Taylor Swift album at an Austin record store and drove that green Honda 1,758 miles to the big city, singing and crying along to songs about breakups and rebirth until I crossed the Brooklyn Bridge.

Despite the challenges I faced when I lived in Austin, I’ve retained my childhood admiration for the many positive attributes that I still think of as distinctly Texan in nature. Texanness is that certain breed of flashy friendliness, a bit of firecracker in the eyes, a hardworking, resilient nature. I admire what seems to be an innate Texan trait, this ability to hold space inside oneself for both rugged individualism and fire-breathing tribalism. It can at times come off as brash or annoying; my dad recalls being flummoxed, as a young Army recruit, by the laughter he received when people he met overseas asked where he was from and he replied, “Texas.” It was explained to him that typically you say “America” or “the United States,” but of course a Texan would cut to the chase.

When I asked my dad to describe what being Texan meant to him, he struggled to outline singular qualities that could not also be ascribed to residents of other hardscrabble places, like, say, Alaska or Wyoming. But when he really pondered Texan qualities, he told me, “I think that there’s a sense that we’re in this together and even if you don’t know people, if you’re somewhere else and you run into another Texan, there’s, like, a bond right off the bat. . . . It’s like you have a lot of common ground real fast.”

Sometimes my mom, like me when I lived in Austin, struggles to find the Texas she loves in the state’s contemporary existence. On a recent visit to my parents’ home in Austin, where they relocated about ten years ago, she told me, “I have Texas in my heart and a lot of the pride, [but] I think Texans now tend to have an overblown arrogance of ‘Everything’s bigger in Texas, and I don’t care if it’s not—I’m gonna make you think it is.’ ”

After spending my adolescence enthralled with the Texas mythos, I tend to see it more as pride than arrogance. Then again, my mom earned the right to criticize her fellow Texans, whereas I will always be a visitor, a guest. A guest who’s grateful for that bittersweet chapter spent living in Texas, because it gave me a textured and unvarnished look at real life amongst the natives.

- More About:

- Austin