This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

We rage against the dying of the light because that is our nature. And sometimes, for the blessed few, the raging takes on a life of its own. Here you’ll read how a small-town editor confronted the John Birch Society because it was the right thing to do, but also because it made good copy. Accused of a crime he did not commit, an El Paso aviator celebrated acquittal with a victory roll high above the heads of his tormentors. A British artist left his family and traveled six thousand miles to find contentment—or at least relief—in a skid-row garret in Galveston. The prattle of a carnival barker, the plaintive whistle of a locomotive, it’s all music to someone.

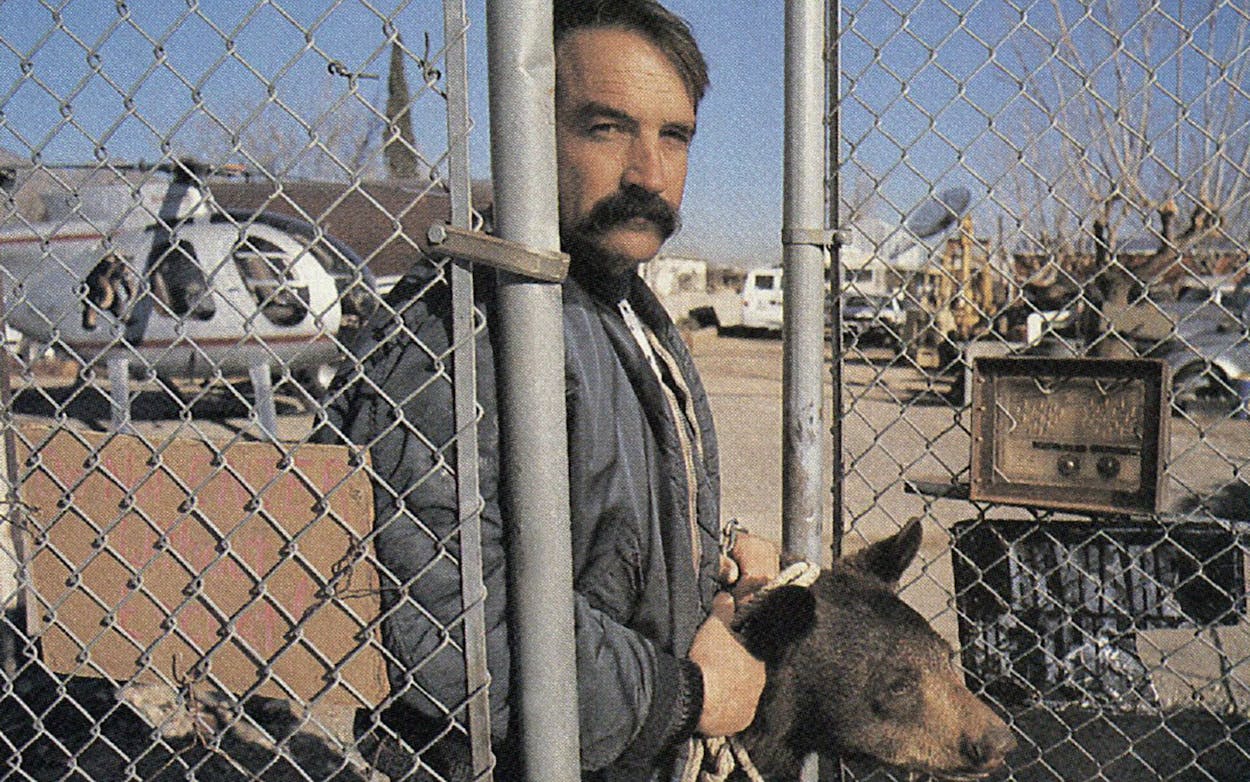

Cheater Bella

Jack-of-all-trades

El Paso

Charles “Cheater” Bella, 44, and his wife, Carrol, live inside a walled, barbed-wire compound near Fort Bliss with an assortment of ill-tempered dogs, a dozen cats, and a menagerie of wild and exotic animals. Bella has been a local legend for two decades, but fame turned to notoriety in the summer of 1988, when a woman hijacked his helicopter and forced him to become party to a prison break in New Mexico. Sitting in his yard, stroking his bull terrier, Bella recalls his ordeal.

I’ve done everything from cleaning manure out of cattle cars to digging ditches. We do charter flying for people, run a helicopter service, automobile repair, heavy-equipment repair, welding and machine work, aircraft repair, whatever it takes to earn a dollar. But the helicopter service probably pays for 80 to 90 percent of everything you see here. We own two helicopters, but one of them got shot up in New Mexico in 1988.

It started when I picked up this woman who said she wanted to look at some real estate, and she pulled a gun and told me to fly to the state prison outside Santa Fe. She said something about how her old man couldn’t do the time and she was dying of cancer and stuff like that. And I looked at her—she was 250 pounds and wouldn’t win a beauty contest if Ray Charles was the judge—and I’m thinking I’m in deep shit because if this ol’ gal thinks that guy loves her, she won’t stop at nothing, because she’ll never find another guy. She was sitting behind me, so I reached back and grabbed the barrel of the gun: It was a short-barrel .357 magnum, and I could identify the hollow-point ammunition in the cylinders. We’re fighting and the helicopter is banking to the left and going nose down and I’m thinking if we go into negative G’s, it’s history. Do I really want to die over this?

In the prison yard three convicts jump in the helicopter, and another one hangs on to the skids. Her boyfriend is slapping me on the head with a gun and saying he’s gonna blow my head off if I don’t get going. The engine is already up to max. I’m pulling it all the way through the temperature range—it should have exploded—and finally they shove this one guy off the skids and one of the guys in the helicopter jumps out and runs alongside it and he climbs back in when we start to lift off. We brush one fence and just clear a second one. The guards are shooting at us, and I’m imagining what it’s like to die, if you see anything or feel anything or just go black.

They didn’t have much of a plan, just land at some airport and steal a plane and go to Mexico, adios. They had bolt cutters, clothes, and stuff, and we’re heading south. I’m keeping low because I don’t want to get mixed up in jet traffic at Albuquerque International but hoping they can see me on their radar. When we finally land, they all jump out. But one of them comes running back just as a U.S. Customs Blackhawk lands a hundred feet away and an agent with an assault weapon jumps out. This inmate’s name was Mitchell; he’s doing life for murder, and he’s got nothing to lose. I know he’s serious because he’s walking right in front of this Customs agent, who is just standing there, picking his nose.

The Blackhawk pulls up to a fifteen-foot hover like he’s going to block my flight path, throwing up rocks and debris, and I pass under him with a couple of feet of clearance. And his copilot opens fire, one airborne vehicle to another, which is against any regulations that I ever heard of. We continue to fly toward Albuquerque; at one point Mitchell wants to know if we have enough fuel to make it back to the prison! I tell him that if he’ll throw out his gun, I’ll land him near the terminal at International, where he’ll at least be in front of witnesses in case they try to gun him down. And that’s what I did.

I’m thinking it’s over, I’ll be home in half an hour, maybe even get a medal, then first thing I know they’re slapping me in handcuffs! Next day they filed charges, saying I conspired with those goons to break them out of prison. To make a long story short, I hired F. Lee Bailey to defend me. The government knew they didn’t have a case, but when you use deadly force on an innocent person, you have to either apologize or claim the guy is part of a conspiracy.

The trial was a joke. They asked me how come a guy who wrestles six-hundred-pound bears for sport gets overpowered by a woman, and I told them, “Look, I don’t allow the bears to ride in my helicopter, and I don’t issue them firearms.” Took the jury just three hours to find me not guilty—it would have been sooner except they wanted to stay long enough to get the free lunch. I was in a hurry to get the hell out of Albuquerque, but I did a flyby over the prison on my way home.

I won the case, but it ruined my business. I still owe more than $100,000 in legal fees, and my deficit last year was over a half million dollars. A half million dollars! Whoever says you’re innocent until you’re proven guilty is full of it.

Marvell E. White

Retired Teacher

Amarillo

White, who declines to give her age, has always worked to foster black self-esteem. In the sixties, when she was an elementary school teacher and counselor, she taught her pupils about civil rights, encouraging them to write national leaders and express their feelings. A warm and energetic woman, she is raising funds to build an African American cultural center at the site of a hospital operated by one of Amarillo’s first black physicians.

I came to Texas when I was married in about the mid-thirties. I guess I could be called a Texan. Sometimes when I have to speak to a group of Texans, I say I had to come from Oklahoma to tell you all about life. When we were growing up in America, everybody was separated. No black teacher or students ever went into a white school, and no white teacher or students ever came into our schools; we never exchanged anything. The only white that would come into our school would be some sort of administrator, and it would be when we had graduation at the high school. Usually they’d come in and just stay long enough to pass out the diplomas.

I think in Oklahoma we had a better situation than we did in Texas. We had to buy our own books in Oklahoma; when we came into Texas they were given to us. See, we weren’t used to that. My daddy would march us down to the bookstore to buy our books, and I think we appreciated them more because we had to pay for them and take care of them. And then we could pass them down to a brother or sister the next year or two.

Now when we came into Amarillo, the children had been going to a school down in the area that they called the flats. Of course, I refused to call it flats because we didn’t name it flats. You see, that’s all over America—wherever black people lived it was flats, bottom, over the track, down in the dugout, or what not.

In Oklahoma my father was a tenant farmer and a carpenter, and my mother was a housewife. I had two brothers and five sisters, and we had to make good grades. We had to study. We all had to get to school on time and make good grades; we couldn’t bring C’s home. My daddy could work any math that we ever had, and he worked it so quickly. And I thought at times that would handicap me, because he would just tell me what to put down. And that’s what I did with my sons, worked it for them.

My sons graduated in ’52 and ’53, both of them honor students and both good at math. We all came out of a good home, a religious home, and I’m proud of it. We obeyed, and we made a contribution to America. Now my parents have gone on and most of my sisters and brothers, and my sons are making their contribution. Gordon is an attorney in Houston, and his son is an attorney too. Warren is an accountant in Chicago. So we are paying our dues, as people say.

Mary Christine Higgins

Retired Secretary

Galveston

She is the daughter of Irish immigrants who arrived on the island in 1921. Her father, Pat Higgins, worked most of his life for the Santa Fe Railroad, which for decades was one of Galveston’s major industries. Mary herself worked 22 years as a secretary for the Santa Fe. Railroads have been her passion for more than half a century, and she can recite schedules, regulations, and railroad lore at the drop of a switch. Over the fireplace in her home on Fifty-first Street is an oil painting of Santa Fe engine Number 3937. A devout Catholic, Higgins, 65, never married, but she always doted on her sister’s children and used to take them to the yards to watch the switch engines.

Daddy was a car man. He worked on boxcars, painting them, working on the air conditioning, working on passenger trains. And in later years, whenever the train came in at night, if they decided it needed painting, then they would call Daddy and I would take him over to the yards, which were at Thirty-seventh and Mechanic back then, and he’d sandblast and paint. And then he’d call me and I’d come back and get him. Santa Fe was very particular about their equipment.

People today don’t realize how much trains were used. We had two trains out and two trains in every day. Number 16 went out in the morning, and Number 5 came in in the morning. And Number 6 went out at night, and Number 15 came in at night. During the summer months, when they had the bathing beauty revues, there would be trainloads of people coming in, and they’d have to pull them into the station, unload the cars, and then back the cars out to the roundhouse to store them until it was time for the people to go back.

I’ve loved trains from the time I was a tiny kid. I knew all the schedules. I would listen at nighttime when they had the steam engines. The neatest feeling was on a cold winter’s night if it was raining and the wind was blowing out of the north and I’d hear the steam engine pulling out. It was kind of awesome. Then, of course, the diesels came along, and they’re fun, but they’re not like the steam engine.

We didn’t have air conditioning in those days, so in the summer, rather than pack Daddy’s lunch in the morning and let it sit in a hot locker, Mama fixed his lunch at about eleven-thirty, and I would pedal my bicycle like the dickens to get to the other side of the railroad track before twelve so Daddy’s lunch wouldn’t be late. Then when I’d get ready to leave, somebody would say, “Mr. Pat”—they called Daddy Mr. Pat—“Mr. Pat, there’s a train coming.” And he’d say, “Oh, she’ll wait.” And I would. I would sit and wait for the train to go by and count the cars and watch to see if there were any sparks coming from under the wheels and the different names of the different cars. I guess because Daddy painted the cars and stenciled the names on them I was a little more aware of the condition of cars than most people.

Once I took my sister’s two boys down on Industrial Boulevard, and we stopped to watch a switch engine. A gentleman from the railroad came over who turned out to have known my father. So he said, “Would you have any objection if I took the boys for a ride?” I told the boys, “You behave and stand exactly where the gentleman tells you.” Ever after, I’ve wished I had a camera to see those kids looking out the window with eyes big as saucers. And the engineer told them, “Oh, I knew your grandfather, Mr. Pat, very well and he was a fine gentleman and you boys should be very proud.” And at that time Daddy had been retired for thirteen years. It’s nice to know that people remembered him in a kind way.

Don Foster

Artist and Sculptor

Galveston

Foster, 37, moved to his studio loft above the Strand twelve years ago, when that section of old downtown Galveston was still skid row. Foster is committed to his work and acknowledges that he doesn’t much care where he lives, as long as people leave him alone. A native of England, Foster studied and later taught at the Royal College of Art—“a nice safe job”—until the sixties, when he decided to move to the United States and become a serious painter. He has families in both countries. A gaunt man with a weathered British face and blond hair gathered in a small ponytail, Foster putters about in the stifling heat of his loft, wearing only a pair of black trunks.

I came over here in ’69 because some of my work was in a traveling exhibition. It was the first time I’d been to New York, and I had planned to go to L.A. but happened to telephone—after having seen man land on the moon—happened to telephone this guy in Houston, and he said, “Why don’t you come down for the weekend?” That first weekend in Houston! Twenty years ago Houston was one of the most vibrant, exciting, electric cities anyone could imagine.

Within two days I was fortunate enough to meet these people who had contacts with the museums and with any modicum of culture that was going on. Suddenly I was a star. I thought, Jesus, I don’t deserve this; this is crazy. In a way it went down from there. But I was totally seduced by the phenomenon, the electricity that I found in Houston. I had a studio on North Main, up near the I-45 freeway, and I could ride a bike from my house to the studio. I loved seeing the organization men in their cars, going downtown every morning, trying to make that buck. But eventually it became too expensive. Galveston was cheaper and not that far away, and I decided to come here.

Survival, yes, I know all about it. It’s possible for me to dress up in a fancy suit and look like a million dollars, you know. It could be that I have a big sale pending, which would blow some fellow artists’ minds, and so, therefore, in terms of exactly how much I make a year and pay taxes on, I’m not going to discuss it.

However, it’s generally very easy for an artist who has suffered any hardship to know how to survive. For example, if I’m short of money, I know that in my collection I’ve got things I can turn over. I’ll sell something, a Picasso like that etching over there, or whatever.

This piece is called the Seaside Incident. It’s not quite complete, but it’s got a stencil of a little teddy bear on a trolley, one of those kid things. I picked up that stencil in a thrift store—I stole that stencil! I slipped it in a book that I paid 25 cents for and my daughter, who was eight years old, noticed, and I felt a terrible guilt. I’ve apologized, but I’ll never get rid of it. I have to live with that shit; isn’t that ridiculous?

The last exhibition I had in Houston was two years ago at the Graham Gallery. I hardly covered expenses. But I’m very fortunate in that over the years I’ve got a little following of people who know me, know my work, know what I’m about. What I do reflects the pain and joy and craftiness and beauty of being alive at the latter end of the twentieth century. My responsibility is to not repeat myself.

I don’t want to go back. I want to be thrilled and excited and stroked by what I’m in the process of doing right now.

Ben Ezzell

Newspaper Editor

Canadian

For 42 years Ezzell and his wife, Nancy, have run the Canadian Record, the weekly newspaper in this small Panhandle town. They do everything from reporting to typesetting, and Ezzell, 73, still frequents the sidelines of high school football games to get the play-by-play coverage and take pictures. Their youngest daughter—they have six children—is the newspaper’s advertising director. Sitting at his ancient Underwood manual typewriter, Ezzell talks about covering the John Birch Society in the early sixties, when the Record became the first paper in the country to expose the ultra–right wing political organization.

The Birch Society caused a lot of damage in this country, but you never heard the name “John Birch Society,” because it was a secret organization. Now, it was strong in West Texas, it was strong in Kansas, it was strong in Southern California and in Indiana. The reason I got onto it was because they were trying to organize a cell here and there were some local people getting involved in it. I was one who had been approached, but we didn’t know what it was. The Birchers were using all kinds of literature, and some of it was old silver shirt stuff—this was a Nazi group. Most of these were organizations that dated to before World War II, but there were no names attached, no identification. It was to be a political movement, and one thing that really stirred me up was that they were organizing to fight communism but they were using communist tactics. They were even organizing in cells. And the selling point was that you would know only the coordinator and the people in your cell; you didn’t have to put your name up front. They would just use your influence and your money.

There was a meeting here in Canadian, and General Jerry Lee, who was the commander of the Amarillo air base at that time, was the coordinator. General Lee was a screwball, but he was above suspicion. A friend of mine—Dr. E. H. Morris—and I started digging, trying to trace this literature they were using, see where the stuff was coming from, and find out who was in back of it. In the course, I crossed paths with some friends in Amarillo, including Tommy Thompson, who was the managing editor of the Amarillo Globe, and Don Doyett, who was the managing editor of the News, and two or three others up there in the newspaper business. We were all following the same leads and couldn’t find where they were going. Finally, one afternoon Tommy Thompson called me here and said, “I’ve got an invitation for us to attend a meeting up here in Amarillo, and I want you to be here Thursday night at seven, and don’t ask me no damn questions.” Well, I’d known Tommy for a long time, so I said, “Okay, I’ll be there.”

The meeting was small, probably not more than 25 or 30 people, and it was held at the Globe News. The people I was sitting with were prominent citizens of Amarillo. What we heard there that night was a filmed two-hour speech by Robert Welch, the candy manufacturer from Boston who headed the Birch Society. That room was so thick with paranoia you wouldn’t believe it. I never took a notebook out of my pocket, and neither did the other newspapermen. We figured we’d be thrown out, so we just concentrated real hard.

It was fascinating. This guy Welch was outlining his whole plan for a political takeover with this secret society. He said communism was progressing worldwide. Then he said the communists have infiltrated the government of the United States and former president Dwight Eisenhower was one of their dupes and so was Mr. Eisenhower’s brother Milton Eisenhower—Milton was a card-carrying Communist. They were also attacking the Protestant ministry out here because they considered them communist. Welch made the case that the communists have already infiltrated the government of the United States, so in order to combat them, we had to go underground and undermine the government.

I had read about sedition, I studied history, but I had never encountered it before. This bunch of people were absolutely seditious. Well, after the meeting, the other two newspapermen and I got out of there and went down to Don’s office and started making some notes and discussing what we heard. But these guys’ hands were tied, because their editor in chief, Wes Izzard, was in with this thing, he chaired the meeting. So I came home, got in about 2 a.m., woke Nancy up, and told her about it. Then I went in and wrote sitting at the coffee table. I had to get it on paper while I could still remember, because I was quoting directly. Anyway, we published our story the next week, on Thursday, the same week as a newspaper in Southern California, so we were the first in the country to open up the John Birch Society. We got letters, about 50 percent hate mail but also letters from people who were so grateful to find out what was happening. I’ve never seen anything like it.

Several years ago a friend of mine did an article on me that he sold to the Texas Observer, and he wanted to know why I used to be conservative and why did I change. I said I didn’t know that I was ever very conservative or that I changed that much, and he said, “Well, you voted Republican—for Eisenhower and then for Richard Nixon the first time around—and what have you to say?” I said, “I guess the best answer I could give you was that I had covered Republican presidents and a couple or three Republican Texas governors, and that made me change.” He said, “Texas has never had a Republican governor.” This was before Bill Clements. I said, “We’ve had several, they just never admitted it.” Also, during the Vietnam War, my daughters were activists, and I had to listen to them a lot, because they were saying things that made sense.

Sometimes, in a small town, you’re very close to the people you’re writing about, but you can’t let that affect the way you handle the news. I think if you try to be very evenhanded, then you can do it. For instance, last Thursday afternoon we printed a story on some arrests made by the sheriff’s office. They were young people—17 to 23, not juveniles—and we used the names. It was flag theft, just vandalism, and several of these people were also involved in trashing the Pizza Hut. We carried the story as soon as the charges were filed.

Well, two of the fathers of the young people came over here in quick succession, and both of them were irate—“All a lie.” “My kid didn’t do this.” I didn’t blame them for being mad. If my kid had done it, I would want to bust him, but I wouldn’t want to bust somebody else for reporting it. It’s been a long time since someone has taken a swing at me. It has happened, but there’s a way to handle these things. My desk is kind of a horseshoe, so I sit behind it; they could climb over it, but they don’t. I talk to them, but I won’t get up out of my chair because that’s a threatening move. So these men came in stomping around, and they wanted to know where I got this information. I told them I got it from the sheriff, it’s on the record. I said, “Look, I’m sorry. I didn’t have anything to do with this happening, but it did happen. You could go talk to the sheriff yourself.” If I had got up and walked around the desk, there could have been fireworks. But they cooled off.

A long time ago there was a story involving the school board. They needed to borrow money to buy a school bus, and the only banker in town also had an insurance agency. When the school board representatives came in, Harry Wilbur, the banker, said, “Where are you going to buy your insurance?” You see—no insurance, no loan. He had pulled this on a lot of people, but he pulled it on the wrong ones that time. They turned around and walked out, but they let the story be known, and the banker made it worse by sending his son to the school board meeting that night with a letter. So the whole thing was in writing.

Well, within an hour it was the talk of the town, and I wrote a story and took a copy over to Mr. Wilbur and laid it on his desk and said, “I’m not offering to let you edit this, but if you have a statement to make, I’ll publish it along with the story.” Then I walked out. In about fifteen minutes he staged a public march across the square and into my office with the chairman of the bank, who was a very wealthy rancher here.

At that time my desk was behind a partition, so I couldn’t see that there were a lot of other people who had followed them in; the lobby was crowded. Wilbur and the chairman really started pressuring me. “You’re not going to publish this,” they said. I said, “Yes, I’m going to.” Then the chairman threatened to put me out of business, and I thought he might be able to do it.

Anyway, it was quite a show, and we had quite an audience out there. A friend told me later there had been betting on the streets about whether I was going to print the story. Of course I printed it, and it had repercussions. For one thing, we got a second bank, and it was the best thing that ever happened to this town. The old banker finally got to where he would speak to me again, although it took a few years. I didn’t see that I had a choice in printing that story: Either they were going to run the newspaper or I was.

A. J. Alamía, Jr.

Psychology Professor

Edinburg

A member of a family with deep roots in the Rio Grande Valley, Alamía, 40, teaches at the University of Texas–Pan American. Controversial and flamboyant—he usually wears a monogrammed Western-style shirt, black pants, gold Rolex watch, and red anteater boots and belt—Alamía is a critic of the admittedly shameful public education system in the Valley and a student of the Hispanic political response.

My mother was the first Mexican American beauty queen in the Rio Grande Valley, back in—she’s going to slay me for saying this—the thirties. My paternal grandfather was a county treasurer and died under very strange circumstances in his forties. My dad’s brother was the administrative judge for this area, J. R. Alamía, and my dad and his younger brother managed the family ranch.

I went away to the University of New Mexico to get my doctorate, but I would have been turning my back on my people and my community if I hadn’t returned to fight discrimination and racism. I owe my community—that’s the name of the game. My grandfather taught me that if we were going to succeed as a people, we had to be color-blind. You have to learn to work with people. But he said something else that I’ll always remember: “Prefiero morirme una vez parado que vivir hincado el resto de mi vida”—I’d rather die standing up once than live on my knees the rest of my life.

My grandfather’s analysis of the economic situation was, “Hey, until we own our own banks, they’ll always control us.” Think about it. You apply for a car loan to get to and from work. But you can’t get a loan because you don’t have transportation. So you lose the job or you can’t get the job that would serve as a springboard. They’ve always found ways in which they can screw us.

When you’re fighting for survival you have a tendency to group in factions, and I still see a lot of factionalism amongst the Mexican American community. You have the old establishment, the new guard, and the bros—the brothers. The old establishment is allied with the Anglo community. And the new guard or young upstarts are the ones who like to do it into the wind and get it all over their boots because they don’t give a rat’s ass. And then the bros, they operate under the banner of golpe pecho. Which means, in essence, I’m beating my heart out; I’ve been discriminated against, and dammit, I deserve something. Okay, here’s a little bone, here’s a little grant, here’s a little fund.

The young upstarts are the professionals—your young school administrators, avant-garde lawyers, people who have a commitment to their cultural values and live and breathe that commitment. I belong to the young upstarts, although I have connections with the bros and with the old establishment because of who my family was.

The bros are different from the young upstarts in that they seem to manipulate the system more as a dependent need. They have started their own banking system, for instance, for the money but also as a means to control people’s lives. The bros contribute—don’t get me wrong—because their survival depends upon filtering some of those fringe benefits down to the grass-roots level. The bros are college graduates, businesspeople, politically active, critical thinkers, analytical. It just seems that they’ve been seduced by the powers that be.

Some people call me an educational elitist. I have two daughters, ages ten and eleven, and they go to a private school, St. Joseph School. My concern is that my children have the best opportunity to develop their minds by the time they reach the eighth grade, which is in another two years. After that, they will go to public schools, because they have to learn to be mainstream. They have to know what a dog-eat-dog world it is out there.

W. A. King, Jr.

Lithographer

Brownsville

One of four children of W. A. “Snake” King—a near-legendary wild-animal importer who supplied carnivals, circuses, and zoos in the twenties and thirties—Bill King, 77, lived a boyhood that could have come from a novel. Diminutive, trim, and straight-backed despite his age, King has been in the graphics business in Brownsville since 1947. Over coffee at a local restaurant, he flips the pages of his 1964 family biography, Rattling Yours . . . Snake King, and reminisces about a place and time in Texas that seem almost unimaginable today.

I was brought up in this atmosphere of wild animals, screaming animals and all. This is a crazy story—any way you look at it, it’s kind of weird. The story begins in Brooklyn—about as far as you can go from where you’re sitting right now—because that’s where my dad came from. His parents came from Warsaw—that’s really the beginning.

Now, my dad was a go-getter, short man, very active, very dynamic. I wish I was half the man he was. Once when he was a kid, he was at Coney Island, and he walked up and down the midway, and then he stopped at a hot dog stand. Here was this great big, husky, redheaded gentleman just about ready to chomp into a hot dog, and here was this hungry little kid looking at him. The guy looks down and said, “Would you care to have one?” He didn’t have to ask twice.

They got to talking, and the man said, “What do you do, kid? Do you have a job?” “No, sir.” “Would you like a job?” “I sure would.” “Well,” he said, “I’ll give you a job.” My dad walked up the midway into the tent, and he no sooner went in there than he came flying out. It was the snake show—we called it the geek show. The man grabbed him on the way out and made him go back. Eventually, he lost the fear that most people have of snakes, and it all started there that moment.

I guess the carnival was there for the season, and then it went out on the road. He got to know other showmen, he got to visit with them and all, and he soon found out the two best money-makers on any carny were the geek show and the girlie show. That’s what inspired him to come to Texas, because the big problem that showmen had in the geek show was that the snakes died.

Anything alive will die sooner or later, but what accelerated the snakes’ death was the fact that the people worked them at night, when they normally rest, so that cut down the short life span. Dad knew all the fraternities in the carnivals, and they wanted snakes, but there was no place to get them. So he decided to open a snake farm—the first snake farm possibly in the world and surely in the United States.

He looked at a map, and he saw Texas. The climate was good, so he moved to Texas. He came this close to settling around the San Antonio–Corpus Christi area, but he figured, “Well, as time goes on these critters are going to get scarcer and scarcer.” That’s when he decided to come to the Valley, right where the Rio Grande runs into the Gulf of Mexico—as far as you can go without a passport.

At that time, all you had to do was walk out there and there were snakes, lizards, whatever you wanted. The pavement ran to about half a mile out of the city, and from there you were on your own—dirt roads. The only means out of Brownsville was a stagecoach to Alice. He almost left the area because the silly people wouldn’t allow the rattlesnakes to travel with him on the stage. I can’t imagine why. I guess they thought they’d slip out or something. The Missouri-Pacific railroad came into Brownsville in 1906, and my dad was here a year before that.

Right here where we are, I used to hunt scaly tree lizards and striped lizards and even snakes and bobcats, and look how it’s messed up now: nothing but concrete and buildings. This was jungle—ebonies and mesquite trees and everything else—just the way the good Lord made it. Now we’re messing it all up, smearing concrete all over everything. They call it progress. I don’t.

Anyway, Dad waited around, and in the meantime, he organized his snake catchers—the Gonzalezes and the Piñedas and God knows how many more—like you see in the book. They look like something out of Pancho Villa. The snake catchers lived out here—you know beyond where Los Fresnos is as you’re going out to South Padre Island? That’s where the ranches were.

The snake catchers would come in every Saturday with snakes, bobcats, leopard cats—a lot of fauna that you don’t find today because this area then was real primitive. They’d come all the way in on the wagon, and we’d take the snakes and weigh them and pay so much for a pound of them. Then the snake catchers would go into town and buy their staples—lard and sugar and coffee.

We sold the cats to shows, and I’ll tell you what: We used to sell a lot of bobcats to Chinese people. They’d buy bobcats to eat them—and snakes, young rattlesnakes. They wanted them only two or three feet long and tender. Dad would write them to let them know that there was a new shipment of bobcats immediately available, and he once got a Chinaman to print in Chinese “Have very fat bobcats right now” for so much, you know, and we’d use that as a translation.

We used to bring young parrots into Matamoros by train from Mexico in cages made of chicken wire. The next thing we knew, though, we were being shortchanged; we’d be missing one or two parrots. Eventually Dad figured out what was happening: The parrots were being stolen along the way by the expressman. So he got into his Model T Ford, and he traced the train. And he saw the guy taking the parrots out and exchanging them for tacos, enchiladas—whatever. That’s when he got the idea of having signs made, warning that these parrots had a very dangerous fever. He got them to put that notice on the cages so the guys wouldn’t steal the parrots.

Once, we went on tour in Mexico with my kid brother, Manuel, who was a lion tamer, and we toured a whole year with a circus. Manuel was the main attraction. I worked a couple of bulls—you know, elephants. The railroad that used to run at that time—the tracks were about that far apart—the cars were so small that we couldn’t get but one elephant in each end of a car. It was a crazy thing.

Here’s a big cage my dad used to fill with monkeys—rhesus, macaques. He’d bring them from India to sell to circuses, carnivals, and zoos. He would bring maybe fifteen or twenty pythons in boxes about the size of this table and about this high, one snake to a box, all coiled up like a bunch of truck tires. The first thing we had to do was take each snake out and measure it. That’s not easy, because how do you take something that big with all those muscles and stretch it out? It’s not going to accommodate you at all. But my dad found a way to do it. A whole bunch of men would hold the snake, and Dad would take a piece of light rope and measure it all down the backbone. Then he’d stretch the rope out, and that was the length. He’d hit it within a few inches.

We used to milk the rattlesnakes and keep the venom to sell. Dad also found a way to defang the snakes to sell to his foremen cronies, so that when the Wild Man from Borneo was in the pit there, you see, the snakes would be safe. When the foremen would order, they would say, “Send me a den of fixed snakes”—a $23 den or a $50 den. Then we’d mix some blacksnakes, some yellow, and some defanged rattlesnakes, unless it was specified “with fangs.” They always had to specify, because one day a man got killed on account of a telegram—by one letter in the telegram. The telegram should have read “one $50 lot fixed snakes,” but they put an n in there, so it was “one $50 not fixed snakes.” We sent them with fangs. The Wild Man from Borneo put them in the pit and he got hit and he croaked.

Now let me tell you something else. Dad’s name wasn’t really King. He got that name legalized after he went into the business. Our family name was actually Lieberman, but that wouldn’t sell any snakes. “W. A. Lieberman” doesn’t mean anything, but “W. A. ‘Snake’ King”—well. He was quite a guy, very well known. Through the twenties and thirties, Snake King was a household name.

Betty Howell

Full-time Volunteer

Amarillo

She has been involved with almost every civic organization in the city, and now she is focusing on historical preservation and the revitalization of Center City (downtown Amarillo). A pretty, impeccably dressed woman, Howell, 50, talks about the life of a volunteer and fundraiser.

All my days are atypical, but I usually get up at six-thirty and leave the house by eight or eight-fifteen to run around town, whether it’s to attend committee meetings or do other things. I also am the volunteer secretary for the music ministry program at First Presbyterian Church, so I try to squeeze in some hours doing that. I never drink coffee—I shouldn’t say never—I occasionally drink coffee, and I do eat cereal for breakfast. Then usually I either take someone to lunch or I don’t eat lunch. I’m not home until late. My family has always laughed that if they ever have a problem, they had better be independent, because I won’t be there to solve it. As a result, they are relatively independent.

My car is my office, although I don’t have a car phone. I wish I did, but my husband says no because my driving would deteriorate considerably. So I stop at pay phones a lot. People ask, “Where are you?” Well, I’m at the Toot ’n Totem at such-and-such corner. That’s basically how I communicate. It’s not very efficient, but it works.

I do have a study at home, but it’s impassable, there’s so much in it. People will call me and ask, “Do you have your files on. . . .” Yes, it will just take me a long time to locate them in the attic. I’m a paper person. I have voluminous piles of paper, and they’re about to inundate me. I use lots of file cabinets and Permafile boxes. I have Permafile boxes all over everywhere. I’ve got to go to computer, I know. I’ve asked, and my husband says, “Well, I’ll give you a computer, but you absolutely have to keep it at home.”

Fundraising is not my favorite thing to do, but I have done a lot of it through the years. And I don’t mind asking, when I believe in something. I think fundraisers always have to initiate the discussion. It’s seldom that anyone calls and offers you x number of dollars. I began fundraising when we were working on the Amarillo Little Theater Panhandle Follies in the mid-seventies. And I had never asked anybody for any money. In fact, back when I was at Amarillo High School, my father sold my fruitcakes because I would never ask anybody for anything. But I found myself in charge of advertising for the theater program. The first thing I do if I’m asking for money is motivate myself. That time I motivated myself with a box of chocolate candy on the seat of the car, and every time I made a call on someone, I had a piece of chocolate candy. I have now progressed past that, thank goodness, or I would be a three-hundred-pound person.

You have to believe in what you’re doing. If a project is something I don’t believe in, I just cannot do it. Then the next thing is to not be intimidated. Just pick up the phone and call the person and ask if you can come visit with them. They always know that I’m coming for something—I’m getting that horrible reputation! The phone call is probably the hardest part. Once you have a hearing, the rest is easy. We usually meet on their ground because my car is not a very conducive place. Then, basically, I just tell the story of what we want to achieve and ask their participation.

I find that frequently it’s good to go in pairs, especially if I’m approaching someone I don’t know. It’s helpful to give a potential contributor an idea of how you would like them to participate, a range or a specific dollar figure. I’ll never forget when we were planning Funfest, and I called on one gentleman. I had the proposal all typed out, asking for a specific amount for a food booth—$400, I think. He immediately said—before my friend and I even opened our mouths —“Well, Betty, I’ll give you a hundred dollars.” And my face just dropped, but I thought, well, I’ve got to be gracious. So I said, “Thank you very much. We appreciate it, and I’d like to leave this paper with you.” By the time I got home, the phone was ringing. He said, “I had no idea you were asking for four hundred dollars. If you will bring that check back, I’ll give you another one.” I think that if you don’t establish expectations, you’re likely to get much less.

The state of the economy has made a difference in what we can expect, though. I recall taking a couple to lunch back when we were working on the cancer center; after that they called and said, “We think we would like to do something in the area of a forty-thousand-dollar gift.” We don’t have that kind of calls now.

Greg Whittaker

Student

Galveston

Whittaker, 22, acquired his love of biology growing up on a farm in upstate New York and came to the Galveston campus of Texas A&M University four and a half years ago. He expects to graduate with a degree in marine biology in May 1991. Last summer he was working as a curator at Galveston’s Sea-Arama Marineworld when a baby sperm whale was stranded on the beach near Sabine Pass. Whittaker was one of the biologists and volunteers who helped rescue and transport the 1,200-pound baby back to Galveston. He is a tall, trim young man with curly blond hair and a shy smile, and he wears the starched khaki shorts and shirt of a Sea-Arama curator. On a hot September morning six days after the beaching, Whittaker pauses from his vigil beside the rescue tank at Sea-Arama and talks about his career and this unique experience.

We’ve nicknamed him Odie because he belongs to a class of toothed whales whose scientific name is Odonteceti. This animal is only about three weeks old, so he doesn’t have any teeth yet—you can see the nubs where he’s actually cutting teeth. It’s very rare that one of these guys was even sighted in shallow water and even more rare that he survived the beaching and the stress involved and that we managed to get him back here. Sperm whales live in deep water, and you rarely see them off the Texas coast because we have such a broad continental shelf. One guess is that the baby was sick, and the mother brought him in to keep him calm and let him get healthy again.

When we got to the beach last Sunday night and realized this was a newborn, we decided to stay with him through the night, try to keep him calm. The mother had been sighted earlier in the evening, so our plan was to give him some injections of antibiotics and steroids and try to turn him around and get him back out there. But in the morning there was no sign of the mother, so we went ahead and arranged for a flatbed truck to get him back to Galveston.

It was a very emotional night for all of us. Usually when you get these calls the animals are already dead, so we thought it would be only two or three hours at most and weren’t prepared at all, especially for something this size. We didn’t bring any food, and the nearest town was thirty miles, and anyway it was Sunday and everything was closed. We decided to break up into shifts. And since we were already in the water and wearing wet suits, we took the first shift, the six of us from Sea-Arama. The park rangers had families to go to and most of the volunteers left, and after a while we felt kind of deserted and stranded out there in the darkness.

It was almost complete silence. The waves had stopped coming in, and we were just sitting there, swatting mosquitoes and looking over our shoulders, expecting to see the mother out there and keeping an eye out for sharks. The surf where we found him was probably a foot and a half, so we got a tarp under him and pushed him out into deeper, calmer water and tried to keep him from floundering. He was scared, which is expected. He’s a very young animal and separated from his mother, but luckily, being so young, everything was new to him, so he probably didn’t react as violently as an older animal would have. We kept things as quiet as possible and were stroking his sides to get the loose skin off—these animals have live skins, and when it’s stressed, it dies and it’s better to get it off. I imagined that the constant caressing was kind of consoling to him.

Only one in a hundred strandings live. It’s been six days now, and so every day we’re getting more hopeful. At least his condition isn’t declining. His muscle tone is good, and we’re managing to get the diet of lactose-free milk down him with a tube—whether it’s the right diet, we don’t know. So little is known about these animals; this is a pioneering experiment.

Oh, you can see his mouth opening right now! See? He’s been doing that. I was in the tank with him most of last night, and we were trying to get him to voluntarily take food. I held my hand underwater about three feet away, and he actually came right up to me and positioned my fingers in his mouth and actually started sucking. I think at that point I really bonded emotionally with this animal. I was underwater and I could see his eyes focusing on me and there was almost a wonderment of him looking around and trying to figure out exactly what was going on. And it was like he almost realized we were trying to help him. He was responding to that, and it was kind of neat.

None of us have had much sleep in the last six days. But I don’t mind the long hours. I’m single and I’m taking off this summer from school and I don’t have anything else to spend my time on. Being a curator is not part of my college training—it’s not a career step for me, but it’s good training anyway.

The best of all possible worlds for Odie would be, first, get him where he’s accepting food from our hands. Then get him on solid food, eating squid, and try to make him understand that squid are alive out there and he’s going to have to chase them. Maybe get some people to actually follow a pod of sperm whales—you see them sometimes near Corpus Christi where the continental shelf is short—and locate their migration patterns so we can put this animal back once we get to that point. I had hoped I wouldn’t get attached to this animal. I know there’s still a real good chance that he could die. In which case we’ve made arrangements with one of the fish houses here in Galveston with a big freezer. They’ll put him in the freezer until they’re ready to do a necropsy. It’s kind of morbid, but this is a very rare scientific find.

(Editor’s note: Two days after this interview, Odie died.)

- More About:

- TM Classics