It’s said that few things are more powerful than the human brain confronted with a challenge. Throw a boy into the deep end of a pool, for instance, and he’ll learn to swim. Give a woman access to kindling, and, if she’s cold enough, she’ll make fire. Tell a man he must avoid strangers by at least six feet to prevent the spread of a pandemic, and he’ll post on Craigslist inviting himself over to suitors’ houses for a foot rub.

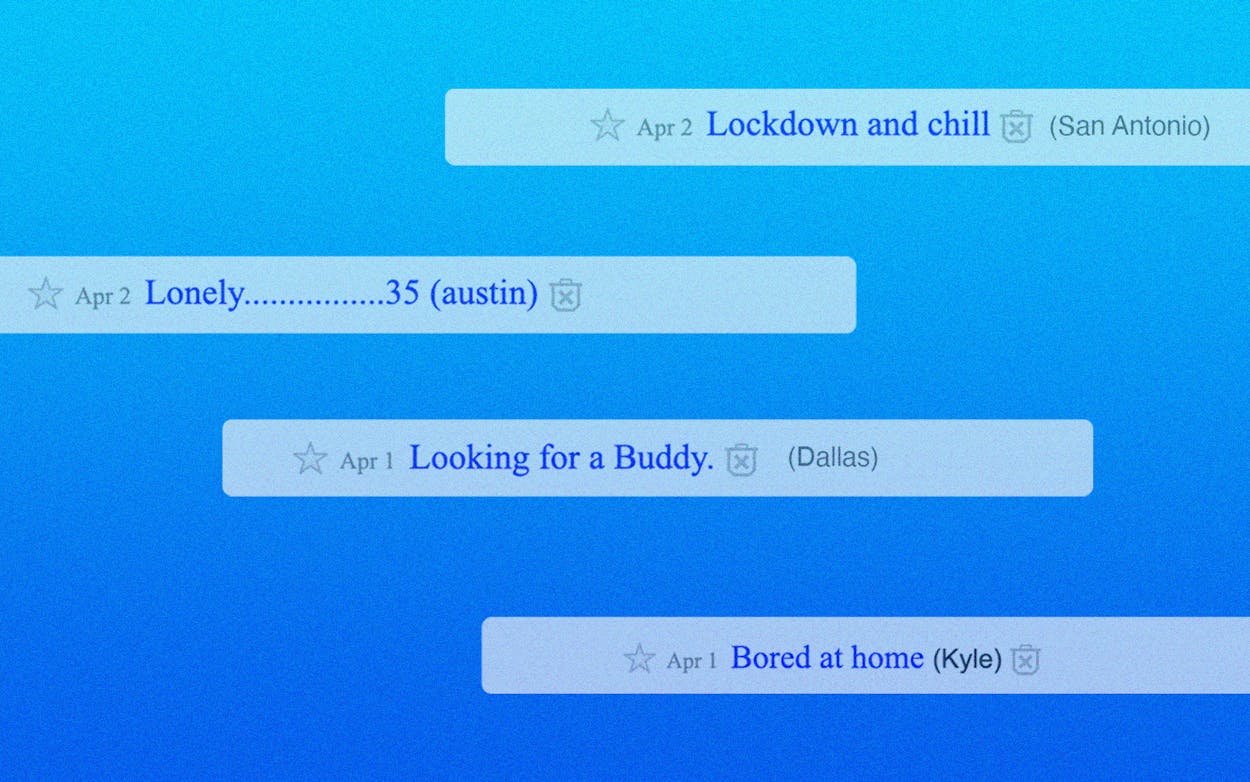

As Texas county judges have instituted shelter-in-place policies that restrict civilians from heading out unless it’s “essential,” one effect has been to shut down basically all activities and places where someone might find a date. Bars have closed. Cafes are open only for food pickups. Even dating apps have issued warnings to users to avoid meeting up with potential flings. Still, Craigslist’s “Activity Partners” pages—a replacement for the “Personals” section discontinued two years ago, after Congress passed a bill that holds websites more accountable when users post ads for sex work—have become a remedial hot zone in the state’s largest urban centers.

On these pages, users can post anonymous ads seeking others to meet up with for recreational activities (a number of posts are scams or disguised posts from sex workers, both of which are often flagged and deleted upon discovery). Some posters are now looking for writing partners, while a few seek weed or pills and a chance to trade rugged individualism for drugged solipsism.

But most recreational posters are writing overtly coded messages treating this time of quarantine and social distancing like varsity cuffing season. One Fort Worth man who was in the market for a “full body massage” thought it would be “fun to have someone join him especially with all this virus stuff keeping everyone indoors.” Meanwhile, a Dallas man invited others over to “practice social distancing,” though he did note, for those concerned, that he was “experiencing buildup.” And a McKinney man beat local lawmakers to their decision to shelter in place by nearly two weeks, inviting women to ride out the duration of the virus with him at his ranch fifteen minutes outside the city. His only requirements? That any prospective partners be equally concerned about COVID-19 and “smart enough to understand this is the only way to stay healthy.”

Some Craigslist posters have noted that proposed workarounds to stay frisky but distant are a “drag.” Absence from human contact has not, it seems, made the heart grow fonder. But it has made the mind settle faster. For many people, the prospect of facing isolation without any social interaction seems to be a nonstarter, no matter how “creative” the solution to make meetups possible must be—from Zoom dates to horseback riding to pulling into another’s driveway and practicing dramatic acts of self-love from the safety of one’s car, as one Frisco man proposed. So they post.

The coronavirus pandemic has also coincided with what public health officials and researchers identify as a loneliness epidemic. While loneliness has traditionally been considered a phenomenon associated with old age, researchers have recently noticed spikes in Gen Z and millennials across the world. A 2018 survey by Cigna found that 54 percent of Americans (as well as 60 percent of Austinites and Houstonians) are lonely. That same year, the UK appointed a minister of loneliness to coordinate a response to the challenge in their country.

Some researchers worry that widespread social distancing might enable those who are preternaturally isolated and lonely to become even more fearful of interacting with other people. But for some on Craigslist, plague has inspired the opposite response. Many feel so disconnected that they have nothing to lose by breaking our new asocial contract. One immunocompromised man in southeast Dallas looking for “action” told me he had heard public figures shaming people for staying out. “They are probably right,” he wrote me, “but hell, I can’t stay in my house alone all the time.”

A large percentage of Texans are facing stay-at-home orders alone or otherwise without family. A quarter of the state’s population lives in single-person households—a percentage that has historically skewed higher in the state’s major cities—and the number of nonfamily residences has exploded in the past two decades. While living alone is distinct from social isolation and from loneliness, the three are correlated. All of them are associated with increased risk of premature mortality, while social isolation and loneliness, in particular, have been linked with increased risk of dementia, heart disease, cancer, and stroke.

The Craigslist poster in southeast Dallas lives alone and rarely ventures out. Several weeks before the county announced a shelter-in-place order, he had been staying home, feeling sick from a change in medication. He told me that before heading out to Walmart to buy groceries and witnessing a run on toilet paper a few weeks ago, he had little sense of the seriousness with which others were treating the pandemic. The Centers for Disease Control guidelines for distance, which threw many others into disarray, hadn’t made life that much different for him—he was already living a socially isolated existence.

When he made the Craigslist post, in which he was looking to “bottom” for someone, he was fully prepared to meet up in person and was confident he could gauge if a prospective partner was sick or not from their cough or lack thereof. But he didn’t necessarily believe he’d find much success. “Usually people just say they are coming and don’t,” he told me last week. A few people messaged back, and he met up with one, but they didn’t have sex.

Two days before the poster and I talked, Dallas County judge Clay Jenkins had issued a shelter-in-place order. But this man wasn’t worried at all about having to evade detection to meet with hookups: Craigslist posters are accustomed to discretion, which is a large reason they post there and not on dating apps such as Tinder.

When I asked him two weeks ago if he was worried for his own health, he told me he had little to lose: “I feel real unattached from the world ever since my parents died. I’m not so worried about me, I’m worried if I’ll affect anyone else.” Reached again on Wednesday, he said he had started to feel differently. An uncle had written him (he said his calls hadn’t been coming through), and the poster had grown more concerned about his health. He was now limiting responses to his Craigslist post to phone calls.

When I told loneliness researchers the stories of Craigslist posters, they weren’t all that surprised. Julianne Holt-Lunstad, a psychologist at Brigham Young University, referenced research that suggests that people who are more socially connected live longer, in part, because others encourage healthier behavior. By contrast, the propensity for some lonely people to take risks is “a testament to how strong the urge to connect socially is,” Holt-Lunstad said. “People are willing to put themselves at immediate risk because the drive is so strong.”

Holt-Lunstad made clear that people should abide by social-distancing measures because the risk associated with the virus is immediate, while serious health effects of isolation and loneliness are more long-term. But she did say that being lonely and told not to socially interact might be like “being thirsty and told the water isn’t safe to drink.” Indeed, one fMRI study from this year finds that people who have been in social isolation for ten hours have similar neural activity when shown images of groups of people talking and laughing as those who have been fasting for ten hours do when shown images of food.

Other Craigslist posters have been trying to fight loneliness by communicating digitally. A San Antonio man and woman who met on Craigslist were trying to cowrite a story—but it took some time to find each other because the initial post was misread by a few as sexually coded, the man told me. A Katy woman who stumbled across the pages after browsing Craigslist’s “For Sale” section found herself in need of conversation—she lives alone with a cat—and posted, “This stay at home stuff is allot mentally.” A number of older men responded, she told me, but to her disappointment she quickly discovered that “most people want sex and not conversation.” Although the post didn’t work as she originally planned, she did mention feeling a new desire to volunteer and socialize more after the pandemic passes. Others have posted about video chatting—an effective temporary substitute for face-to-face contact but not a full replacement, according to researchers like Amy Banks, a founding scholar at the International Center for Growth in Connection.

Of course, video chatting and Craigslist posting aren’t equally shared resources: a 2016 comptroller report found that 31 percent of rural Texans don’t have access to high-speed internet, and Laredo and Brownsville were among the worst-connected cities in the country. Recognizing this problem, Kathryn M. Daniel, a gerontological nurse practitioner and associate professor at the University of Texas at Arlington, told me that one of the biggest health interventions public officials can make in the future is increasing broadband Wi-Fi access to all community members.

Many researchers have attributed the loneliness epidemic, in part, to the rising age of marriage and lower rates of childbearing. Over the past half century, the median age of first marriage has risen by nearly eight years for both men and women, to 30 and 28 respectively. The fertility rate has dropped from 3.5 births per woman to 1.8 over the same period. There are more single Americans now than ever before. Many single people are decidedly not lonely. But for some, the lack of a partner and a family can exacerbate feelings of loneliness.

While “Who has quarantine worse” oneupmanship has flourished on social media between single people and those with children—akin to schoolyard conversations about who got less sleep—those with family members, at the very least, have someone else to talk to. Anthony, a Waxahachie man, followed his mother to the Dallas area more than a decade ago after being honorably discharged from the Marine Corps. He enrolled in school to become a film technician, but just as he was graduating his mom died of cancer. Since then he’s been feeling “stranded.” He has four roommates in a place he found on Craigslist, but other than passing conversations in their shared kitchen, he doesn’t interact with them much. On weekends he works at a Dallas warehouse deemed an essential business, so he’s still been conversing with coworkers. But he says he doesn’t have anybody, really, to talk to. “I had friends from film school, but ten years go by, people drift away and settle down,” he told me. “Now the only socializing is with people at my job, and we’re not hanging out after work.”

In service of finding company, Anthony periodically posts on Craigslist. His quarantine post was headlined with a call for a “mistress/dominatrix,” but its text indicated he would be open to just watching a film and ordering takeout with someone. “I’ve always been kind of shy and quiet, and now with all the closing of most public places and social distancing has left me feeling more alone than ever,” Anthony wrote in his post. When we talked he suggested he was nervous about the ethics of leaving the post up online, and he had practical concerns as well: he usually vets those who reply by meeting them in person at a public place to screen for safety and avoid scams. Now that was no longer an option.

Two weeks after he posted it, Anthony’s ad remains on Craigslist. While he says he hasn’t met anyone yet, he suspects he can tolerate social distancing longer than most. “I’m a single male with little to no friends and family and suppose the need for social and personal interactions goes against my better judgment,” he told me. “I’ve been doing this for ten years, but other people are fairly new to this. Starting out is harder. Some people will hit breaking points and need to go out.”

The comment wasn’t lost on me. I had just moved to a new city myself—from Santa Barbara to Austin—and have few friends in my new dwelling. The coronavirus hadn’t ceased my social interactions, but it had certainly calcified them: I could still FaceTime with old friends, but Travis County’s shelter-in-place order had put a cap on meeting new ones for now. My loneliness, like a craving for junk food, wasn’t so much manifesting as longing as it was boredom; I had too little to do with my days. But to my solitude’s discredit, it lacked the rancor of heartbreak or the romance of ascetic denial.

I thought about downloading dating apps for the first time since a breakup and felt the slight embarrassment of thirst. When I relented and began swiping, one woman I matched with told me the apps were great for entertainment during empty days, but there was only one problem. Conversations typically ceased when she told people that, no, she wasn’t willing to meet up.