Mexican cuisine, though broadly popular in Texas today, has long been the target of denigrating epithets and imagery. Think “Montezuma’s revenge.” Or descriptions of, say, an enchilada platter as a heavy, greasy “gut bomb.” And let’s not forget Taco Bell’s talking chihuahua. A personal favorite is the wildly sensationalistic accusation in a 1910 El Paso Herald op-ed article that “Death Lurks In Tortillas.” For centuries, travelogues, newspaper dispatches, and government regulations associated Mexicans and their dishes with danger. Among the best documented victims were San Antonio’s chili queens. These women set up food stalls in the city’s plazas, including near the Alamo, as far back as the 1880s. At first, they were welcomed, garnering favorable mentions in travel guides and magazines. But local opinions changed. The vendors and their food were eventually viewed as potentially perilous to one’s health. Politicians regulated the chili queens out of business by the 1940s. And you can hear echoes of this history in a word that’s still used in the name of at least one tortilla business: “sanitary.”

As Monica Perales, associate professor of history at the University of Houston, tells me, “sanitary” was a common term during the Progressive Era of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. As Americans moved away from family farms and into cities, reformers pushed to establish food safety standards, ushering in such measures as the U.S. Pure Food and Drug Act. Prior to that 1906 legislation, “There were no laws about how you would sell food,” Perales says. “You had carts selling milk that was spoiled.” Suddenly, there were sanitation fairs, such as the one held in Chicago in 1865, as well as state and industry sanitary boards. Names with “sanitary” in them also popped up in other businesses, from ice cream shops to dressmakers.

But even positive reforms can harbor a dark side. The new emphasis on cleanliness inflamed longstanding prejudices against Mexicans, say Perales, who authored Smeltertown: Making and Remembering a Southwest Border Community. Mexican cooks and restaurateurs, well aware of the stereotype that their food was supposedly unclean, began using the word “sanitary” in business names and marketing materials. In a McAllen Monitor ad, Charro Cafe invited customers to “inspect our sanitary kitchen,” which was “up to the best American standards.” “Using ‘sanitary’ can help assuage concerns that people might have about our food. They highlighted the sort of modernity of their business,” Perales says. “These machines that can make tortillas without having to be touched by any hands, which can also be coded as, you know, ‘Don’t worry. Mexicans aren’t touching your food.’”

One basis for the stereotype was that in some Mexican American neighborhoods—including San Antonio’s West Side—sanitation services were still limited into the 1950s. Some still had outdoor privies without sinks for washing hands. Activists and politicians, many of them white and middle-class, were more focused on optics than on solutions. “Reformers who are sometimes well-intentioned, sometimes not … look at these communities and say these places are dirty and disease spreads very quickly. And it’s sort of a quick leap to the stereotype.”

Established in the midst of this controversy, on September 1, 1925, was San Antonio’s Sanitary Tortilla Manufacturing Company, which retains that name to this day. It made—and continues to make—tortillas via nixtamalization with mechanical tortilladoras that founder Francisco Garcia imported from Mexico. The business claimed it was the first tortilleria to do so in the U.S., in a Spanish-language ad that ran in the Prensa newspaper shortly before the company’s grand opening. This and later advertisements for the company emphasized sanitation, healthfulness, and the use of machinery. “Tortillas made with the hands, the kind that most of you have been eating till today … comes from SWEATING HANDS with plenty of GERMS,” read an ad in the San Antonio Express. The same advertisement asked, “Have you felt bad indigestion or stomach trouble when you have dined on Mexican dishes in some restaurants …?”

In 1931, the San Antonio Express gave Sanitary Tortilla a big endorsement. It called the operation a “progressive and flourishing organization” whose tortillas are “made without the touch of human hands and under the most sanitary conditions.” This praise stands in stark contrast to today’s preference for tortillas made by hand in small batches, according to centuries of tradition, especially at restaurants with Spanish-language or indigenous names. Think Comedor and Mixtli.

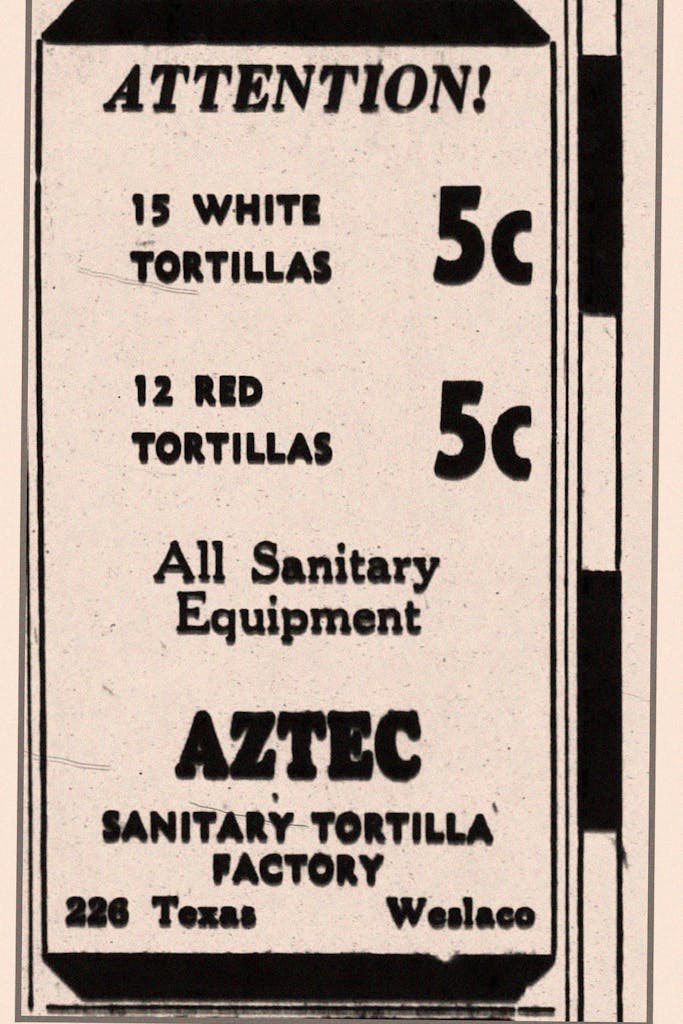

The emphasis on sanitation was a statewide trend. In 1938, the McAllen Monitor ran an advertisement for the Aztec Sanitary Tortilla Company in nearby Weslaco. Fifteen white corn tortillas were priced at five cents. Twelve red corn tortillas also cost a nickel. In 1952, a profile of Tony’s Tortilla Factory in the Austin Statesman mentioned that owner Tony Villasana’s flagship tortilla line was called Tony’s Sanitary Tortillas. That product lent its name to Villasana’s Houston tortilla factory. In Bryan, Grandma’s Sanitary Tortillas doubly signaled safety—not just with “sanitary,” but also “Grandma’s,” a word that evokes the comforts of home for white consumers, instead of “Abuelita’s” or another descriptor.

Like most food businesses, the old “sanitary” factories had short lifespans. Tony’s in Austin is gone. Its former East Seventh Street address is now home to Wilder Wood Restaurant & Bar. Only a squat metal silo remains from its previous life. Where Grandma’s Sanitary Tortillas once stood in Bryan now sits a house. San Antonio’s Sanitary Tortilla Manufacturing Company might be the last of its kind.

Luis Garcia, current owner of Sanitary Tortilla, says that he’s never seriously considered changing the name of the business: “The name has a lot of prestige in San Antonio.” Garcia believes that the tortilleria has been a part of the city for so long—Luby’s Cafeteria was one longtime client—that residents today don’t give much thought to the significance of the name or its history.