Confession: I did not closely follow the Ken Paxton trial until Friday. During Day One, Day Two, and Day Three, I was out of state on vacation and logged off. Like someone who starts watching a show mid-season, I was initially confused about all the in-jokes and assumed knowledge. Who is “Eric”? Was the saying “there are no coincidences in Austin” actually a thing people say? Why did Paxton’s defenders keep dragging George P. Bush into their narrative? The truth is that the Ken Paxton story, including this trial, is complicated, with many more plots and subplots and minor characters than War and Peace.

Now it’s my duty to try to get you up to speed on Day Five, a busy day. It featured the Galaxy Cafe, a red car, and a Bible verse. The bulk of the day featured testimony from two former high-level Ken Paxton deputies. Mark Penley, who served as deputy attorney general for criminal justice, described to the Senate a pivotal meeting with Paxton at a Dunkin’ Donuts in McKinney in September 2020. Penley hoped that it would be a Come to Jesus Moment for his boss, who, he increasingly worried, was under the sway of Nate Paul. That morning, Penley—a staunch Christian conservative—had woken up early, at 5 a.m. “I felt like the Lord woke me up and impressed upon me that I needed to get ready.” He studied his Bible, lingering over Zechariah 7:9. (“administer true justice.”) He wrote out a list of bullet points to try to persuade Paxton on the Paul matter.

At Dunkin’, he told Paxton that it would be “very dangerous” for him to continue pushing for an investigation into the federal investigation into Paul. Paxton, he said, was not persuaded. Instead, the attorney general expressed empathy for Paul. “He said, you don’t know what it’s like to be the target of a corrupt law enforcement investigation,” Penley said. Paxton, he added, doesn’t trust the Department of Public Safety director and feels like the state police ran a corrupt investigation into him resulting in his indictment on felony securities fraud charges.

Penley didn’t say it, but the implication was that the state’s top law enforcement officer identifies more closely with a criminal than the cops.

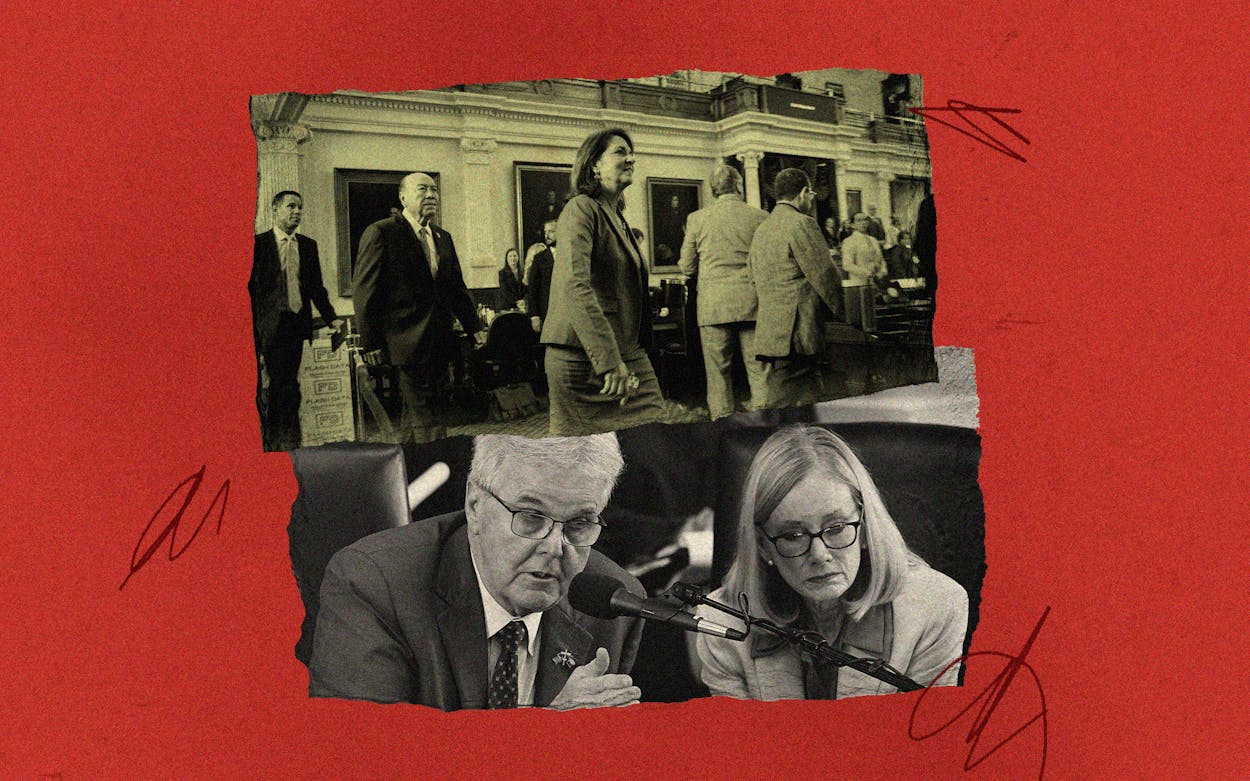

Later, Paxton’s former chief of staff, Missi Cary, took the stand and The Affair entered the frame. As Paxton’s wife, Senator Angela Paxton, watched from a few feet away, Cary testified to one of those weird Austin coincidences. One day in spring 2018, Cary was eating lunch by herself at the Galaxy Cafe when she overheard a loud conversation between a woman and a man at a nearby table. Though Cary wasn’t allowed to get into the particulars–defense attorney Tony Buzbee objected that the specific discussion constituted hearsay—she testified that the woman, who drove off in a red car, discussed certain “personal details” that concerned Ken Paxton. She said she later told Paxton about the disturbing conversation and he assured her that the woman was his realtor. Later, Cary attended a conference in San Antonio where she saw the woman again. Her name tag said “Laura Olson,” who Cary soon realized was Paxton’s mistress. Paxton had lied to her.

But that wasn’t the end of it. In September 2018, Paxton invited his staff to a meeting where he confessed to the affair. It was an emotional moment, Cary testified. A “sad and embarrassed” Angela Paxton cried. The affair was over. Except it wasn’t (allegedly). In 2019, she said Paxton confessed that the affair was ongoing and seemed at pains to explain to Cary that “he still loved Ms. Olson.”

But what did the affair have to do with the trial? Prosecutors tried to establish that Paxton’s infatuation with Olson had interfered with the functioning of the AG’s office. Cary said she told Paxton that “it wasn’t my business who he was sleeping with” but warned him that a secret affair could open him up to bribery and misuse of office. It’s astonishing how often Paxton subordinates warned him of what has actually come to pass.

The defense, for its part, hammered a few key themes. First, Paxton’s lawyers returned to the idea that the AG whistleblowers went to the FBI with only circumstantial evidence. They weaved a story: Mark Penley only began speculating that Paxton was possibly being bribed after he thought his job was in jeopardy. And he went to the FBI with corruption allegations to gain whistleblower protections and save his own skin. The whistleblowers, attorneys for Paxton seemed to suggest, were overzealous Boy Scouts who refused to look into what could have been wrongdoing by federal authorities.

Buzbee, in particular, was in fine form today, turning the screws on witnesses and generally engaging in the kind of hyper-aggressive lawyerly swagger that has made him regionally famous. At one point, he suggested to Cary that her memory wasn’t very good. He almost derailed Harriet O’Neill, one of the defense attorneys, with relentless objections. He attempted to humiliate Gregg Cox, a prosecutor in the Travis County DA’s office who had drafted a memo outlining potential Paxton crimes, called as a witness by the prosecution, by pointing out that he had later applied for a job at the AG’s office. Ultimately Buzbee appealed to the character of the GOP majority of the Senate—highly partisan, highly religious. All have sinned in the eyes of God. Only one man has ever been perfect. “Imagine if we impeached everybody in Austin here that had an affair,” Buzbee said. “We’d be impeaching for the next 100 years, wouldn’t we?”

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- Ken Paxton