Almost 45 years ago, the shores of Vũng Tàu were lined with dinghies. In them were people just trying to get to international waters, in hopes that other nations’ ships could bring them to safe refuge. When thousands of people evacuated Vietnam to flee the Việt Cộng during the fall of Saigon in April 1975, the owner of one small angling boat was also preparing to leave. The boat owner’s friend, Cậu (Uncle) Tài, persuaded him to take an additional five people with them: his sister and her boyfriend (my uncle), my other uncle, my mom, and my dad. Seeing the danger in overloading his boat with strangers, this man could have left them all on land to fend for themselves. Instead, he let all six of my family members pile into the pontoon and drift outward, until a Taiwanese battleship eventually rescued them.

Following the refugee process in Guam, and with a little luck, my aunt, uncles, and parents ended up in Little Rock, Arkansas. It was nothing like Saigon, where they’d grown up, or the American television shows they’d seen depicting sunny California beaches and jagged New York City skylines. But no matter. They were in the United States now, and they were encouraged by their sponsors to get jobs so they could support themselves. So they each found work wherever they could, including in restaurant kitchens, delivering furniture, and cleaning schools. To them, America—the land of opportunity—was about surviving.

One day, a man approached my uncle Cậu Tiên to help him sell clothes. He started small at first, selling surplus inventory. Eventually he began tailoring clothes too, which evolved to include alterations, and recruited his wife and siblings away from washing dishes and janitorial tasks to help with the store. A year after arriving to the U.S., my family started their own small tailoring business, in the middle of downtown Little Rock.

Little by little, they spent their tailor shop earnings on small luxuries. My dad wanted to buy a dependable camera, so he bought the same one that the Apollo 11 crew took to the moon. The family got a house to share between themselves in a nice neighborhood, and eventually Cậu Tiên bought an orange Datsun B210. With the new car, they ventured out in every direction, to explore a new country that didn’t exactly feel like home yet. My dad took his camera on all their travels, documenting their adventures across New Orleans, Pensacola, Memphis, San Francisco, Galveston, and Washington, D.C. It wasn’t the moon, but a different world nonetheless.

This is where my parents usually end their oral history. While growing up in the Houston suburb of Alief, my older brother, Anthony, and I filled in the story’s gaps and contextualized their tales with 45 photo albums’ worth of sepia-toned pictures. We would laugh at how young everyone looked in their early twenties, with their perms and fancy clothes. In some photos, my family is happily posing in the store. In others, they’re hard at work.

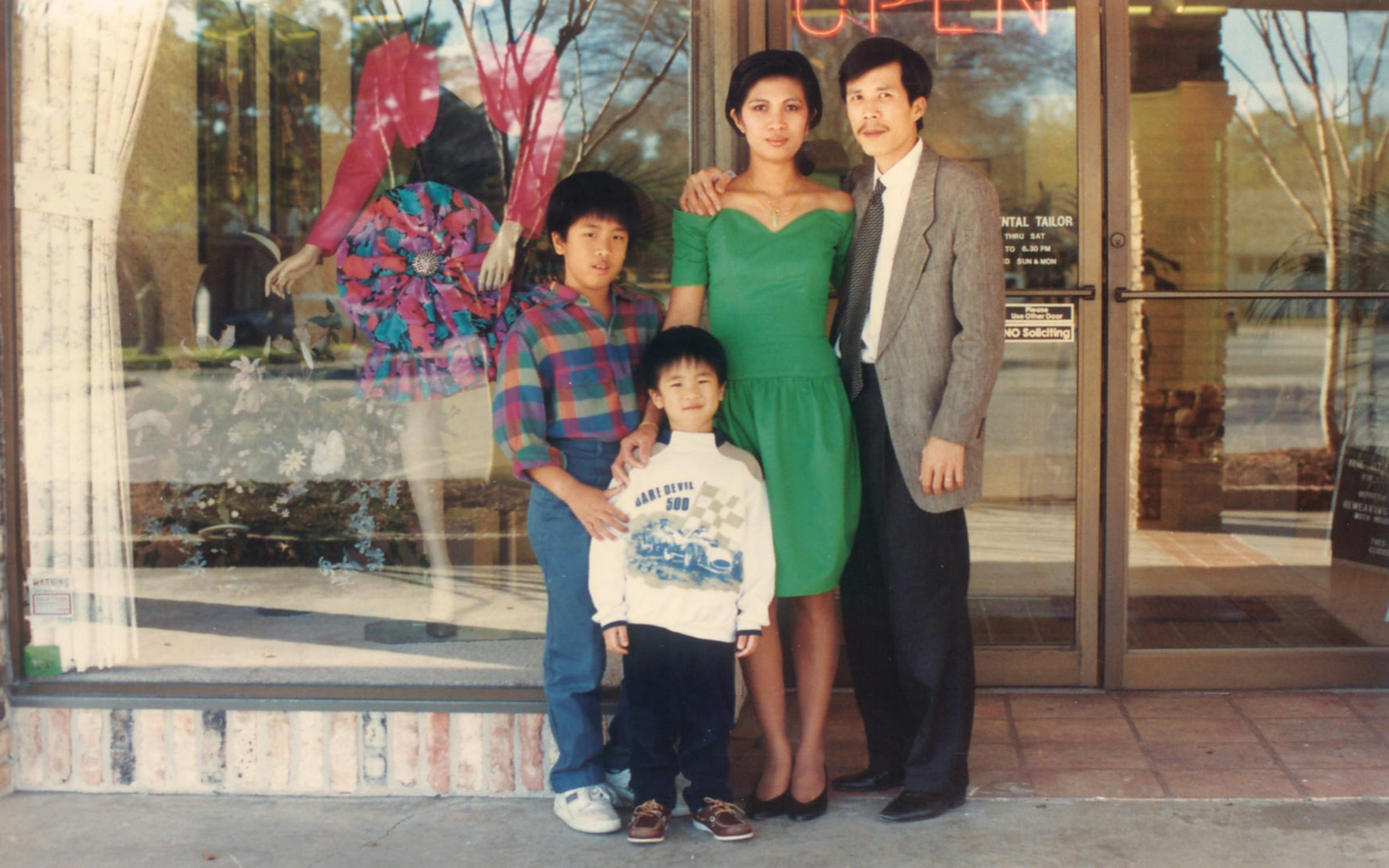

Outside of these photographs and the story my parents often told, my brother and I didn’t know much about the history of the tailor shop they came to own first in Little Rock, and eventually in Houston. The pictures didn’t explain how Cậu Tiên opened a men and boy’s clothing store next door to the tailor shop in Little Rock, and combined the businesses to become Tailor’s Artistry. Or how Cậu Tiên then helped my parents research good neighborhoods to move the shop down to southwest Houston, where it currently stands. During their time in Little Rock, my parents yearned to be back in a big city close to the beach, not unlike the one they left behind. It was a chance for them be with a large Vietnamese community again, and for their home to be within five minutes—not five hours—from a Vietnamese grocery store, too.

For several straight weekends, Cậu Tiên, Cậu Thảo (my mom’s youngest sibling), and my dad moved store furniture from Little Rock to Houston, and in 1981, the Oriental Tailor Shop finally opened in Town and Country. These days, the shop’s name raises some eyebrows. A customer once asked my mom, “Does that word offend you?” My mom said no. (She takes more offense when people mispronounce the word “crawfish.”) What really offends my parents is when people try to take advantage of them because they’re Asian; my dad once chased a guy out the store after he accused my dad of wrongdoing.

When their store sign officially went up, a man excitedly rushed in. “Did you have a store in Little Rock?” he asked. My dad said yes. The man said, “I just moved from Little Rock, too, and I’m so happy you’re here!” Mr. Robertson and his wife were among my parents’ first Houston customers, and have been regulars for nearly forty years, along with their children and grandchildren. They aren’t the only multigenerational clients my parents have. When I asked why they think their customers are so loyal, my mom just shrugged and said, “We do a good, honest job.”

Some longtime customers who see me in the shop today recall how small I used to be—that makes sense, because the shop also doubled as my daycare. My mom bought a sleeping mat, books, and wooden blocks for me to play with while she and my father were working. There, my brother and I watched black-and-white TV shows and drew comics in the break room as my parents sewed away. One time, my dad came by, drew a perfect re-creation of Garfield, and walked away without saying a word. It left me in awe.

As we got older, the shop became a second home where we’d do schoolwork, wait to leave for our soccer games, and play with our toys on the sewing tables, which messed up their machine settings. My mom tried to get Anthony and me involved in the operations, asking us to greet customers and grab their garments from the back.

It didn’t take long for our family to embrace Texas. Maybe Little Rock would’ve felt like home eventually, but my parents loved how friendly and values-oriented Texans were. By reading about the Mission Trail in Texas travel magazines, learning the word “y’all” from television, and having daily interactions with their customers who taught them little things about the Lone Star State, like how to cook a turkey, they became Texans while still staying true to their Vietnamese roots.

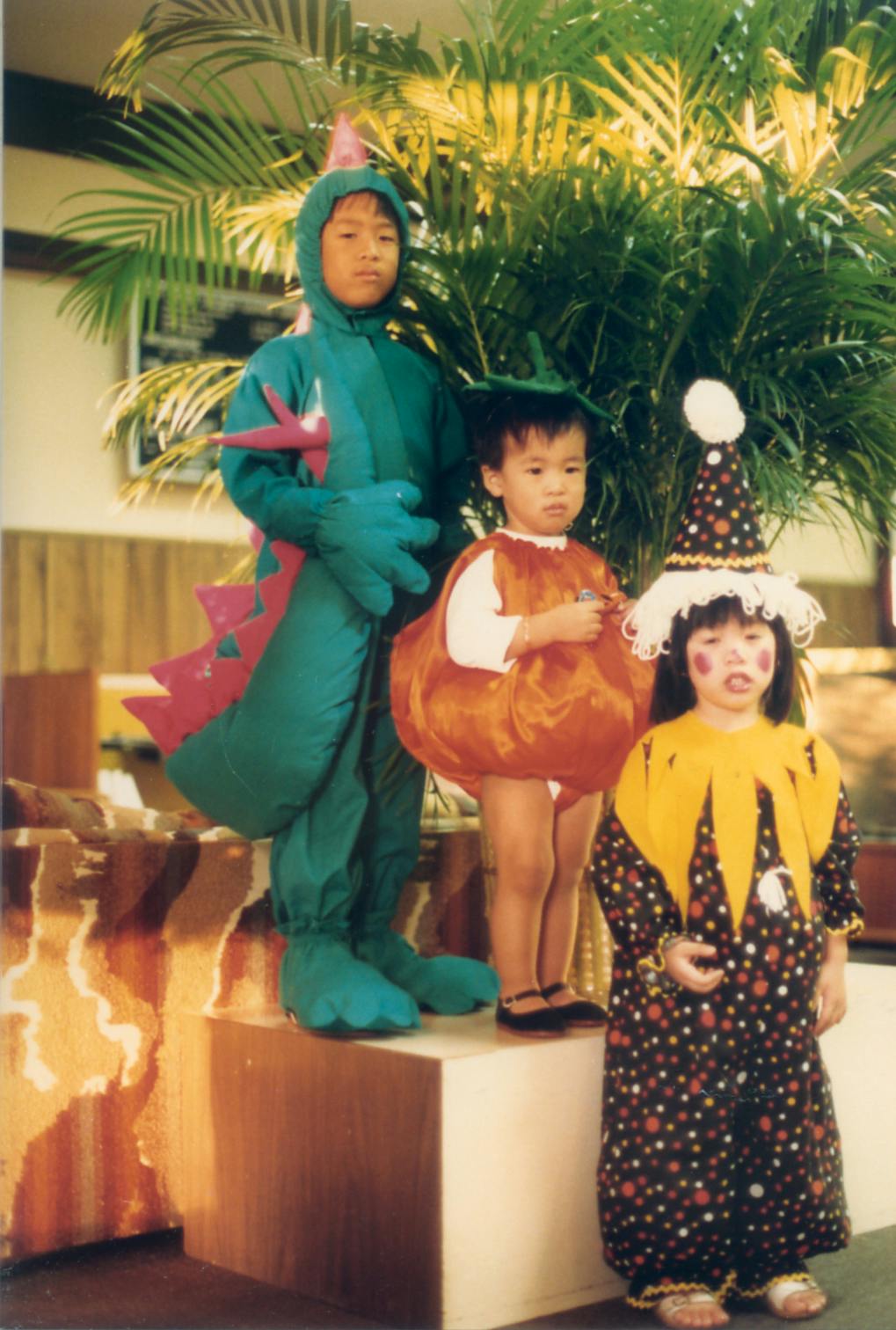

My parents wanted Anthony and me to do the same. We went trick-or-treating in elaborate, homemade Halloween costumes my mom made without sewing patterns. She sewed a pumpkin outfit for me, a head-to-toe dinosaur costume for my brother, and a clown outfit for my cousin. For the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo, our parents assembled outfits from department stores for my brother and me, so we could fit in as cowboys. My mom taught me English from textbooks she bought at the teacher supply store, but we also spoke Vietnamese at home and donned our áo dài during Tết, the Vietnamese new year. And I cannot recall a single dish my mom makes, regardless of its country of origin, that doesn’t have fish sauce in it.

Through their clients, my parents learned things like where the bluebonnets and wildflowers bloom in Brenham and about the German settlement north of San Antonio, Fredericksburg. On random weekends, the four of us would go on short vacations to these nearby Texas cities, with a camera in hand.

The early photographs depicting my aunt, uncles, and parents were intended to document their new American lives. They took pictures of each other for themselves, but also sent some photos to their families who were still in Vietnam so they would know what they were up to and that things were okay. In a strange way, these images comforted me as well.

Before Hurricane Rita was scheduled to make landfall in 2005, my dad rainproofed the house, and my mom locked her most precious memories and photographs of her family in a waterproof safe with the linens. I’m sure she would have saved all 45 photo albums if she could, but that would have been logistically impossible. After the storm passed without much damage done to our home, I never wanted to risk losing these archives of family history again and decided to digitally preserve every single picture.

As I was scanning these photographs of my brother and myself coming of age in the store, I realized that my parents grew up with us there, too. It’s weird to think that parents grow up at all, especially since my mom and dad are ageless and their confidence never waned throughout the years. They studied fashion trends at department stores, tailored beautiful dresses specifically for their mannequins, and adapted with the times. More recently, the shop became half an art gallery to feature photographs of their travels around Texas, from the Renaissance Festival to bluebonnet fields, proving that it was always more than just a tailor shop and they were more than just tailors. They’re multidisciplinary artists who are proud of all the work they’ve done, and want to make their store lively.

This winter, my brother and I will be helping them close the store so my dad can begin his much-deserved retirement after 43 years of running it. My parents will finally be able to take a long vacation and give my brother and me a personal tour of Vietnam, the country they once called home. Undoubtedly, we’ll be getting history lessons and anecdotes to help better understand their perspectives, their lives, and what it means to be a Vietnamese refugee. I couldn’t be prouder to call them Bố and Mẹ.

As a second-generation kid, I often feel guilty because I take things for granted. I moved to New York City to pursue a career in advertising, but never had to flee Alief. I relocated to Europe, but brought more than just the clothes I had on. I’ve worked hard, but never labored. And maybe that’s what my parents’ goal was this whole time.