This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

He has always been a hero. Right from the beginning back in Mt. Vernon, when he was a kid playing football on summer afternoons with the radiating Texas heat shimmering along the ground, Don Meredith was already Something Special.

“If I could just put heat on that film,” Meredith says, his extraordinary pale eyes narrowed against the intensity of his vision as he talks about the movie he plans to begin in July. A documentary movie about Texas high school football. A film written, directed, and narrated by Don Meredith. “That heat . . . somehow we’ve got to shoot it so they can know exactly what it’s like, so they’ll know what I’m talking about. And that dust blowing . . .”

It didn’t take long for Mt. Vernon to recognize that this boy—why, he was a natural! The entire town gloried in his football triumphs, from high school playing field to the winning of an Emmy for his sports broadcasting on ABC’s Monday Night Football.

After all, isn’t that the Chamber of Commerce dream of every small town—that it will be the nurturing ground for a genuine All-American hero? Someone to be the HOME OF on the billboards that greet those restless hoards of cars that rush by on the superhighway. Someone to laud at Rotary luncheons, whose hand you can shake, whose back you can slap. Someone to whom you get close enough to catch a whiff of glory, fame, success. Someone to prove that the American Dream is true and real and that life in places like Mt. Vernon is not futile, but means something or else it couldn’t have produced a boy like this, could it? An All-American, a handsome, strong, laughing hero with eyes as incredibly transfixing as the faded blue Texas sky. This boy who could always throw and run and think and lead other boys; this boy who—most important of all—wins. Yessir, Don Meredith is a winner, and he’s from our place. A good place. A hero’s hometown.

“I think there’s a reason why so many of the NFL players are from Texas. And I think there’s a good film there.” Meredith speaks quietly, his famous drawl soft and slow. He sits huddled in a chair, a big man with a patient, almost old-fashioned courtesy. “There are lots of stories from lots of different towns. I want to talk to the boys, the Moms and Dads and sweethearts, folks down at the feed store. I want to get their attitude about it.”

Meredith is a natural and effective actor. Suddenly, easily, he slips from his own collected, modulated personality into the role of a back-home, Texas-style father-figure. “Why you doing this, boy?” he asks, his voice and inflection perfect. He sounds like he could play the governor of Texas. Just as quickly, he returns to unassuming urbanity. “It is interesting,” he says. “because I have talked to the boys and the response I’ve gotten makes me want to pursue the idea for this film. People think it’s for different reasons, but a lot of it is very, very basic.”

Yes, I suppose that it is basic. As basic as my memories of fall nights when the sky arched high and remote and the air was so clear and cold that gulping it would cause your lungs to ache. Light poured down from tall poles. The grass on the field was even and glossy except in front of the players’ bench where the ground was bare, packed dense and hard by the impatient stamping and pacing of anxious feet. Twined in crepe paper color, the goal posts stood against the darkness. And the rickety wooden scoreboard bore two words: VISITORS and HOME.

“Pro football isn’t what it used to be—but then, it never was.”

In that brittle fall night I sat high on the bleachers, my nose pink and numb, my hands clumsy in woolen mittens. My legs were wrapped in a blanket to protect them from the wind that whistled through the open space under the wooden benches. Below, boys I knew became strange and mysterious champions, knights of a wordless allegiance—the home team. Those familiar boys who copied my math papers, passed me notes in history, and kissed me in the dark shadows of the churchyard, now leapt and twisted, ran and weaved, flinging the ball into the darkness only to pluck it safely back before the night could claim it. On that field the boys were our champions, carrying with them our colors, our songs, our honor. I shouted and cheered until my voice was gone.

Well, the world is older now, and so am I. My rituals have changed. Now I sit in my temperature-controlled house watching famous young giants perform intricate maneuvers on the small screen of my television set while Don Meredith, Howard Cosell, and Frank Gifford supply me with information and companionship. Football has become television.

Cameras roam the field, moving in on a face, capturing a lightening-quick move in slow-motion, showing the details of the game instantly replayed. Just how far is it from those high school playing fields to this business of television entertainment? As I searched for the answer to this question, Don Meredith proved a good guide. He understands both worlds. As football has undergone the metamorphosis from school game to an entertainment industry, Meredith has changed from high school hero to media personality. He understands that television has altered the way that we, the fans, perceive the game and its personalities.

“Because of my television ‘role,’ ” Meredith says, “With Howard Cosell cast as the black-hatted guy and me, the white-hatted guy, a lot of people are sympathetic and feel that Howard really runs over me and picks on me. I’m like their little boy.”

Meredith is candid about this, too. “It’s a hard thing to keep your head together,” he says, “Because there are lots of people in the past that you’ve had respect for, and you thought you had a rapport with them; and then you realize, why, these people didn’t have the faintest idea what you were all about.” The expression in his voice is not bitter, but it is knowledgeable. And wary.

Could it be that Mt. Vernon has given a dual legacy to her gifted native son? Everybody knows of his strong and developed strain of quick, effective country humor. Frank Gifford remarked that Meredith could say “Good morning” and it would be funny.

But there is another trait—more subtle but equally strong—a trait of tough, country-boy shrewdness and native intelligence. (Meredith himself hints at this trait when, discussing some incident, he describes himself as being “very country and sensitive.”) These tandem attributes seem to balance him and enable him to sort out the terms on which he wants to live.

Don Meredith wants to pursue an acting career. But, again, he is wary. “I’ve been interested in acting for a long time,” he explains, “but I went into the stock brokerage business after I got out of pro football. I really didn’t like it at all. I was trying to wear another hat and—well, it was bad. After a year I knew that this was something I didn’t want to do anymore, so I decided to pursue something that I liked. I made a choice to be an actor, and I signed with Dick Clayton, a very fine motion picture agent whom I met through Burt Reynolds. But the tough thing about my getting into acting is that they still want me to do football coaches and football players, ex-football players. Those roles just don’t interest me at all. Occasionally, there’ll be a Western or a war movie—but still I’d just be an ex-football player.”

One role that Meredith would like to have played is the role of Gid in Molly, Gid and Johnny, the movie adaptation of Larry McMurty’s novel Leaving Cheyenne. “I’ll guarantee you I could have played Gid,” Meredith states flatly. “And I could have played it well. Because I feel Gid. Man, I know that character. Gid has lots of problems, but when you grow up in a small town, you know about certain things . . . Like some of the hangups about religion. About how someday those streets are going to be paved with gold and there’s gonna be milk and honey for everybody—but now you’ve gotta suffer. It’s hard to break out of all that. And its hard to stay out, too.

“There’s a lot of vanilla in the character of Gid,” Meredith muses, “And at the same time, he’s strong. But then, man, he’s weak in a lot of respects . . .” Meredith trails off, thoughtful. Then he shrugs. The part of Gid has gone to Tony Perkins.

“The power of TV never ceases to amaze me. I never felt it more strongly than two years ago, when I went on the banquet circuit after our first season. I attended 47 banquets in about three months. Man, I covered Middle America and boy, it was frightening! Howard was really hated that first year. What was frightening to me was that these people were serious! They were really serious!

“It became a social thing to discuss Monday Night Football. It was more than a fad. They listened and they would hang on every word. I’m not trying to say that we, the announcers, were more than the game—no, they were football fans first—but they really became involved in what Howard and I were saying. That was truly frightening. Because this was the first time ole Dandy Don had gone to places like Easley, South Carolina or Davenport, Iowa or Columbus, Georgia. It was very educational for me . . .”

It is easy to sense how this insatiable demand to share his life can consume a person. Many an American myth-figure like Meredith has experienced the corrosion of the soul which can be the result of too much adoration, too much unceasing attention.

“Hypothetically,” Meredith says, “I would like to do two movies a year. But I have no ambition to do a movie just to say, ‘Hey, I did a movie!’ For that reason, I may never get to make one. Because I’m not going to do just any part. I’ve had opportunities to do roles both in television and motion pictures, but they were like I described earlier. No, I’ll just wait until something comes along that offers me a chance to be more than an ex-football player.”

Would the public be able to accept easy-going, humorous, exuberant Dandy Don as a reticent, repressed, weather-beaten Texas rancher? How would they accept the knowledge that Meredith, like Gid, has a side of his character that is locked away from public display and that “the good ole boy” that keeps Gifford and Cosell company at the Monday Night Football game is only one role played by a complex and introspective Don Meredith?

“A lot of people think that Howard and I hate one another, when really, just the opposite is true,” Meredith says. “I really love Howard. He’s a beautiful guy.”

But if the role fits, Meredith plays it, especially if the role is good show business. The Emmy that gleams upon a bookcase in his apartment dramatizes just how well Meredith understands television.

“This medium is powerful,” he explains. “Last year they told us that more people watched one of our games than the total all-time audiences of Gone With The Wind, From Here To Eternity and The Music Man combined. More people saw that one game than have seen Hamlet since it was written.” He shakes his head ruefully.

“Ever so often I look up and see it and I think,” once again, Meredith is acting, “whewwww, man! You’re strong, boy! You’re strong!” He drops the acting and says quietly, “It’s so strong that it’s changed the whole world.”

Meredith is also sensitive to the impact that television has had on the sport with which he has been associated for so long. “The effect of television on football has been tremendous. For me to give the full impact would be impossible, because I’m not aware of all the financial transactions. But I don’t think it is any big secret that, without TV, the growth of football would have been delayed a great deal. I don’t believe that football, without TV, would ever have become as big as it is right now.”

It is Meredith’s contention that the visual power of televised football captures the fans. ”In the last four or five years, the television coverage of football has gotten very good. The esthetic side of football has been brought to the American public. People can see and appreciate the fact that a guy six foot six, weighing 270 pounds, can move as though he were in a ballet. They can see that it’s a matter of physical coordination in a way that couldn’t really be appreciated before.

“Television,” says Meredith, “has also brought to the public more of the players’ personalities. For many, many years, the football player has been stereotyped. Television has made a great breakthrough in giving people another idea, the idea that a player is not just some big, dumb . . .” Meredith finished the thought with a grimace. “Some of them are,” he says, “but most of them are college-educated, and a lot of them are very sensitive people. Hopefully, some of this quality is coming across. If it does, there will be another section of fan that will watch the game and appreciate it for these attributes.”

But Meredith is not completely easy with the marriage between television and football. “There are dangers inherent when the game becomes so much an entertainment. Now I am nowhere close to being any kind of authority, and this is strictly my observation. But you have two different things here—a sport and a fine entertainment package. It depends on how people watch it.”

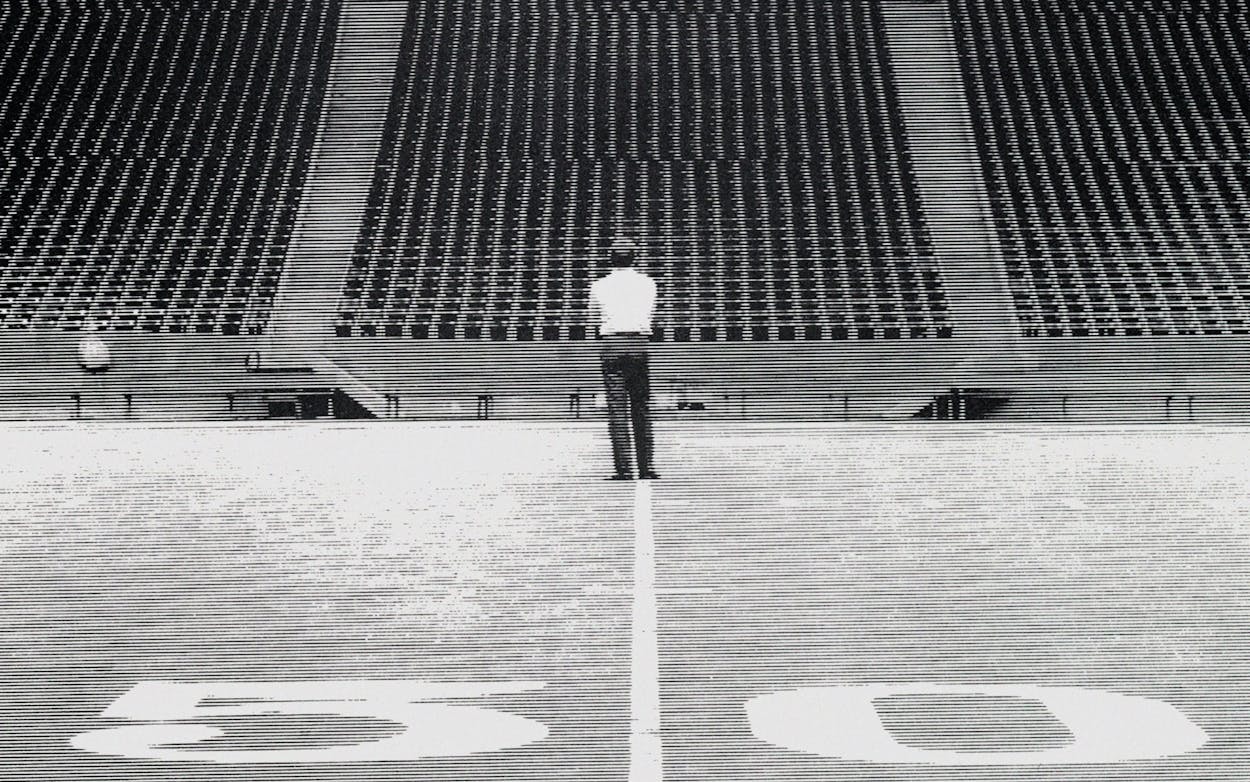

How we watch it depends in large measure on what we see, and what we see—the plays, the players, the announcers—is the product of some of the most intensive, pressure-filled work one can imagine. To the man controlling the cameras, Don Meredith is just one element in a never-ending flow of choices about what is to appear on our television sets. Choices, that is, about what action we see, about what we will think of Don Meredith versus Howard Cosell, and about what football on television will be like for us. The men who make those choices take a fierce professional pride in their work.

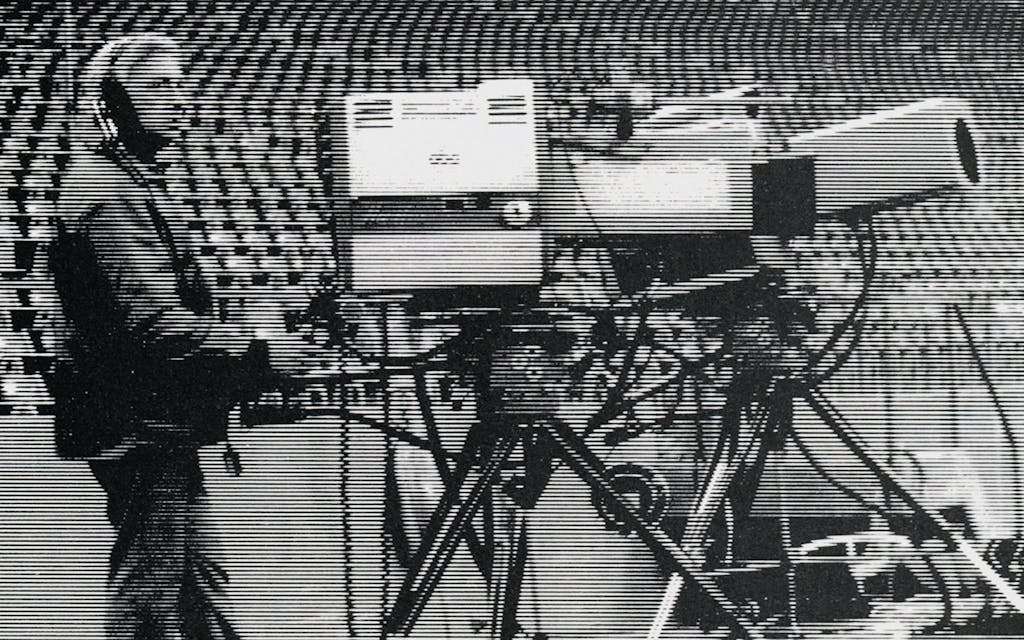

Chet Forte glares at a wall of 19 TV monitors, each reflecting a different view of Texas Stadium. None of the images are bright and clear enough for the director-producer of ABC’s Monday Night Football, the man who decides what we see, both of football and of Meredith.

“What’s the trouble, huh?” Forte demands loudly. “What’s going on here for Christ’s sake?” A basketball star in his college days at Columbia, Forte is a small, compact, intense whirlwind. Everything he says comes out fast, emphatic and a little shrill. “Somebody got a light meter? We gotta measure that light and see if they’ve got what they say they’ve got.”

Every Sunday night during the football season Forte sits before an altar of various sized TV screens and speakers that is wedged into a tiny space in a large trailer truck. He is flanked by his young co-producer Dennis Lewin and another assistant. The three of them sit intent before the images that flicker in front of them.

“Try video,” Forte commands. “See if they can brighten it up, huh? This is pitiful!” he moans. Next to him Dennis Lewin is speaking softly into the headset mike he wears. This Sunday-night rehearsal ritual is designed to test the cameras and lenses Forte uses in his constant attempt to get in close on the action.

“I’m always looking for tighter shots,” Forte had explained earlier, discussing his craft. “That means putting a tighter lens on the camera. Regularly, a cameraman on the 50-yard line, if he has an 18-to-1 lens, may be able to crop, on his widest shot, say 25 yards. Well, I take the 18-to-1 and put an element on it. With it, this cameraman may now only be able to crop 15 yards at his widest. This puts an awful lot of pressure on my cameramen.”

Not only does Forte have to see what his cameras can do in the stadium, but he has to be certain that the technical engineers (called “video”) can use the picture that results from these elements. “Sometimes video can’t handle it and they’ll say, ‘Chet, you have to get back a little wider.’ Then I say okay, because our picture quality has to be good. So I may be forced to go wider. That’s why we have this rehearsal. It lets me find out what the camera can do.”

A figure appears in the doorway to the control booth. “Chet,” he says quietly, “we don’t have a light meter.” It is one of the 50 crew members that mill industriously around the three trailer trucks of equipment.

Forte groans, “What is this, huh?” he says disgustedly. To him, lighting is the most important attribute of a stadium. It takes good lighting to get good pictures. “In some stadiums, like Minnesota, the lighting is dreadful,” Forte said. “When a stadium is a problem for telecasting, it is usually because of the lighting.”

“Whattaya think,” he says to Lewin, motioning toward the wall of screens, “you think it’s the monitors?”

Lewin shrugs. “Could be,” he says, dubious.

Grimacing at the dim images, Forte leans toward his mike and demands of a cameraman, “Okay, let’s see what you’ve got.” Diana, his pretty young friend, appears on one of the larger screens. She and Jack Gallivan, the technical director, are standing in for Cosell, Gifford and Meredith. Tomorrow night, the “talent” as the announcers are referred to by the technical people (with a slightly patronizing tone), will stand there to introduce the telecast.

The inside of the trailer looks something like the NASA control center if it were compressed by a car-crushing machine and jammed inside a truck. In addition to the wall of monitors, there are a bewildering array of switches, buttons, telephones and microphones in front of the three men. Every image that the nine cameramen focus on is fed into this tiny space for Forte to select what will appear on the television set in your home.

“I have full control,” Forte maintains, “because nothing goes on the air until I say it goes on the air.”

The sharp eyes and the quick reflexes that made him a college basketball all-American in 1957 are still in evidence as Forte clips out orders rapidly, his New York accent sharp and imperative, his eyes always moving, catching every detail.

Suddenly he turns to the writer who is peering into the truck from the doorway. “Your guy got a light meter?” he asks. Startled, the writer can only stare at him. With a quick movement Forte indicates one of the small screens, which shows the magazine photographer and two of the crew technicians standing on the field staring intently at something in the photographer’s hand. The writer nods. The photographer, almost forlorn with his tiny camera amid the millions of dollars worth of ABC equipment, does, indeed, have a light meter, which is quickly pressed into use.

“Good,” Forte snaps. “Camera two, let me see that shot without the element,” he says, shifting his attention without breaking stride.

“To be very honest with you,” Forte had remarked, “I’m known in the trade as a real bastard. I extend my cameramen because of the coverage I want. I put an awful lot of pressure on them because I want to get tighter into the game. This makes it tough on the cameraman because he has to pan on passes—he has to do a lot of tough things. But,” Forte says, emphasizing each word, “these guys do it. These guys have been with me for three years. At times I know they’re really sweating it out, but I’ve never had a guy come to me and say, ‘Jeez, that lens is too tight. I can’t cover the game with something like that!’ No. These guys just keep working at it.”

During the two hours of rehearsal, the crew works efficiently and with purpose. After three years, they know what Forte wants and they work hard to get it. “These cameramen were handpicked,” Forte said. “I knew these guys would work hard. I knew that what I wanted for this show, these guys would break their tails to get for me. I remember a shot on the first game we did. It was Cleveland and the Jets. Joe Namath had just thrown an incomplete pass, and instead of leaving the field, he just stood there for a moment in a cloud of dust with this look on his face and in his body—well, it was the kind of shot you would remember.

“My crew is the type of crew that is not only looking for game coverage, they’re looking for those shots that people will remember. These cameramen have developed into very creative guys. Christ, when you’ve got your cameraman thinking for you, too, what else do you want in this business?”

Before Forte is content with the rehearsal, he reviews the graphics and sets the opening shot—a pan of the sky through the hole in the roof. No detail escapes his inspection. Although there is a separate director and producer for Unit B which handles the isolated-play, Forte still calls all the signals. Earlier, Forte had remarked that, in football, the quarterback is the crux of the game. In the telecasting of Monday Night Football, Meredith, Cosell and Gifford may carry the ball, but Forte calls the plays.

During each pressure-filled moment of the three hours of telecasting, the control center in the truck will hum with continual interaction between cameramen, announcers, engineers, technicians, directors, producers. And sitting in the center of this storm of energy and effort will be Chet Forte, calling the signals that determine what you see in your home. From a commercial to the name of a player, if it appears as a part of the telecast, it is because Forte decided that it would.

“The most important person is the viewer,” Forte states. “We want to give him the best possible game we can, the best possible coverage. I’ve got to mesh all the stuff together so we can create the story, get the meat of it. I know exactly what we’ve got, and it’s up to me to make the right decision as to what goes on the air.

“We’ve got to hold an audience. When things are dull, many times I’ll go to Howard to get him to jazz things up. I’ll get Howard and say, ‘Jeezus, you guys are pretty dull up there. Howard, needle Don a little bit. Get Don to mix it up a little bit, get into Frank, get it going.’ We’ve got to hold an audience! We’re primetime viewing. I’ve gotta buck a movie on NBC, I’ve gotta buck Bill Cosby. People get down on my back and say, ‘Hey, you try to push yourselves off as show business people.’ Well, that’s exactly what we are. If anybody says we’re not in show business, they’re crazy. They are absolutely nuts! That’s exactly what we’re doing on Monday Night—show business.”

In any of its myriad forms, show business has a tendency to make gypsies of those who ply the trade. The ABC television crew is no exception. They begin arriving in town on Friday, spend Saturday and Sunday and Monday in preparation. On Monday night they perform. Then, like circus performers, as soon as the show has ended they immediately begin the strike of their equipment. By early Tuesday morning, they are gone, on their way to the next town.

“Sometimes,” a young crew member confided, “I think that all of America is simply the same motel corridor endlessly repeated with the same ugly carpet and fake paneling on the walls.”

“And the same lousy food,” his more jaded co-worker commented sourly, poking at the Claes Oldenburg-like assemblage on his plate. “Would you believe that at breakfast today, this place wouldn’t serve eggs any way but scrambled?”

The younger man laughed. “I asked the waitress why they couldn’t just fry the eggs rather than scrambling them,” he said. “She said that they were already cooked, and scrambled eggs was what we were going to get, like it or not.”

“This place is so bad,” the second guy continued, “that even the hookers who work it are dogs!”

“Why do you stay here?” I asked. The young man shrugged. “We always use this motel chain. Some sort of deal the show has with them, I guess.”

He looks across the table, his eyes old and tired in his boyish face. “Sometimes you don’t even know what town you’re in because all places seem just alike. Lobbies, rooms, airports, rented cars—all of it is the same.”

“You’ve really got to like this business to take the hassles,” remarks the cynical companion. “There is always something going wrong—lost luggage, messed-up reservations. I’m beginning to wonder if anything works right in this country.”

“Well, at least you have the admiration of the groupies,” I remarked, referring to the young women who seem to gather around anything relating to football, including the television crews who cover the game.

The more experienced crew member lit a cigarette and inhaled wearily. “Even the groupies look the same,” he sighed.

“It’s a hard grind, but its challenging,” muses a member of the production staff, “because it’s live television. When you’re telecasting live, it’s more demanding, but also more exciting. Sports broadcasting is about the only live television there is.”

“For me,” Forte asserts, “live telecasting is where it’s at. When you put together a telecast where the cameras are good, the announcers are good, the shots are good, you sit down afterwards and say to yourself, man, we were just on the air for three hours! Three hours—doing isolated camera replay stuff, talking to the announcers, working nine different cameras and sometimes the blimp with a camera, too, and everything live. Then somebody comes up to me and says, ‘Hey, did you see that beautiful show so-and-so did for Sonny and Cher?’ Now that is a hell of a show, but those guys have time and they use video tape. They can do it over if they blow it. Because we’re live, we only have one time—right now.” Forte paused, took a breath, then plunged on. “Don’t get me wrong. I’m not putting down the tape shows. It’s just a different medium from live telecasting.”

“I love live television,” Forte said. “I‘d love to get live stuff like the old Playhouse 90 back again. This is the stuff I’d like to do eventually. The live shows we used to have on TV—some of that stuff was fantastic. The medium puts pressure on you when you telecast live, but sometimes you get better performance out of your people. So what if you flop now and then or blow your lines occasionally? Live broadcasting is the heart of the medium.

“Those of us in sports broadcasting know this better than anybody. Wherever ABC Sports has been with Wide World of Sports or the Olympics in Mexico City or Grenoble or Munich—wherever we’ve been, it has been live. And it has always had this exciting quality. If we could take this live quality over into other areas of television, it would be great. Roone Arledge would be great with this kind of stuff.”

Arledge, the President of ABC Sports and the Executive Director of Monday Night Football, is a constantly-felt presence around the production, although he did not arrive on the scene until late Monday. Meredith is on the air because of Arledge.

“Arledge is a programming genius,” Forte stated unequivocally.

“Arledge was the one who hired Don Meredith after a thirty-minute conversation . . .”

“It was Roone’s idea to use the three announcers . . .”

“It was Arledge’s concept to have the two-unit coverage of the game . . .”

“Roone was the one who had the idea for the award-winning billboard that announces the show . . .”

“Arledge was the one who brought Cosell and his hard-core reporting into football . . .”

Time after time Arledge was acknowledged as the generator of the ideas that shape and distinguish the telecast of football.

Forte is candid about the Arledge method, “By looking for the tighter shot and the inside reporting on sports, Arledge puts a lot of pressure on people. But by putting that pressure on you, he makes you better. Arledge brings his people along and teaches us by putting us under pressure. But I think we all want that pressure. Arledge has the ability to get the best out of people, even if, sometimes, it is by dastardly means.

“If he doesn’t get the best out of you, you’re not going to be around. He’s not an easy man to work for. Yet,” and here Forte actually paused for a minute, “he’s an easy-going kind of guy. He will call you up to say, ‘Hey, the weather is fine in New York, the leaves are falling. Outside my window I can see Central Park and its beautiful.’ ” Forte shakes his head. “But he’s definitely a genius when it comes to programming. I understand he is getting to some other kinds of live television now, other than sports. He’d be terrific with that kind of stuff.”

Forte sits in the truck watching the overcast Texas sky appear on the monitor. “Okay,” he says. “That’s how we’ll start tomorrow night. If there’s a moon, we’ll try to get it in the picture.” Rising abruptly, Forte breathes deeply and flexes his shoulders. “Think that does it for now.” He looks at the ten or more crew members who are jammed into the small space and standing outside the door. “Anything else? No?” he nods once emphatically. “Okay. That’s it.” Then he moves quickly out the door of the truck.

All is in readiness for tomorrow night, when this truck, buried deep in the substructure of Texas Stadium, will be the nerve center for an intricate web of communication, weaving through the stadium and out across the land from sea to shining sea. Communication. That’s what this effort is all about. Not only communication between Texas Stadium and the nation, but communication among the television crew as well.

“That’s all our medium is. It’s all communication,” Forte shrugged. “Whether it’s among those or us in the truck, or whether I’m talking to a cameraman or slo-mo or videotape operator or to the announcers—the whole thing is a chain of communication. If the communication among all of us goes well during a game, 90 times out of a 100, we’ve probably had a hell of a telecast. If there are arguments back and forth, or if there are plays where I’m not communicating to Cosell, or if the replay is off, or we haven’t told Don what the isolate is or who’s making the tackle or something like that, then . . .” and he shrugs again, “we miss it.”

He leans forward, intense and concentrated. “The chemistry only comes by working together. You hope you’re going to get some kind of rhythm to a ball game. It’s hard for me to describe what it is, that rhythm. You just know it. It’s when things are going right and the shots are there and the guys in the booth are doing their thing, and every cameraman is on, and you feel it,” he says. Then he leans back, relaxed. “You just feel it. And you know it’s good.”

Don Meredith, for all his appreciation of what television has done for football, has some reservations. “I hope that football doesn’t become overly saturated or overly-emphasized,” Meredith says, his voice thoughtful. “As far as football is concerned, you have to remember that, basically, it is only a game. To try to make it anything more is to do an injustice to the game and to the American public who watches it on television. I think there is a fine line; you really have to be careful.

“I don’t know a lot about the mechanics of football, but I think that I have a pretty good ‘gut-feel’ about it. This is what I’m trying to get over . . . what I really feel about the game. Howard says that he is bringing a ‘touch of journalism’ to football telecasting for the first time. Well, there are several types of journalism. In a way, I’m bringing a type of journalism to it as well. Maybe a kind of personal journalism.”

It is evident to anybody who spends a few moments in front of the TV set on Monday Night, or who has heard any of the many anecdotes about him, that Don Meredith is a charming, warm, spontaneous human being who rushes at experience with all the naive gusto you would expect of a kid from Mt. Vernon. But that is far from being the total story. There is a skeptical quality to this man, perhaps more hidden and protected, but equally strong. He trusts his instincts and follows where they lead him, and this headlong plunging into life yields a variety of results. But, whatever these results are, they are coolly examined, evaluated, and filed for future reference. When Don Meredith chalks up one for experience, the chalk marks are deep and lasting.

“This past off-season, I worked on things that I wanted to say on television—ideas, philosophies, attitudes—and I’m trying to work them in. Some of them I’ve gotten in; some of them I haven’t. I’m still not pleased with what I think could be done, because this is a beautiful opportunity. It’s quite heavy when you think about all those people out there. You can really do a number on their heads. So you have to be really careful and sure of yourself. Sure that you’re doing it well. One of the disappointing things about what I do is that a lot of folks miss what I said. They heard me, but they weren’t listening. And that is frustrating.

“But then you say to yourself, ‘I’ll figure out another way to do it.’ Not only is there the constraint of the compressed time, but there are also two other guys in the booth whose heads may not be where your head is. So there are a few little obstacles to overcome if you want to get your thoughts in there in the way you think you ought to do it.

“The odds are, when you do manage to say something, there will be some listeners who understand. But you never know. In Houston I said, ‘Pro football is not what it used to be—but then, it never was.’ That’s a line that I don’t expect everybody to get. But if somebody out there gets it, then they are going to look at football in a new way. If they can get into that idea and realize that everything is always changing, even football, and it is nothing to get hung up on . . . Well, I thought that was really a super line. But Frank and Howard looked at me in the booth and said, ‘Whaa-a-at??? What’s that you’re saying?’ ” Don Meredith smiles his friendly, famous smile, but his eyes are detached and knowing.

With Meredith’s words of wisdom about professional football not being what it used to be, if it ever was, still working in my mind, I had come to the point to test the pudding for the proof. My first professional football game, in person, was at hand. Dallas versus Detroit, Texas Stadium, Irving, Texas.

Texas Stadium, from where Don Meredith would soon be broadcasting, is almost an architectural obscenity, a giant concrete dumpling afloat in a stew of asphalt parking lots and expressway intersections. That was how it seemed on a dense night last autumn, with dirty gray clouds hanging low in the sky and with the stadium, like a squatty malevolent candle, drawing toward itself a multitude of innocent, moth-like automobiles.

We parked in one of the many parking lots, all of which adhered strictly to that canon of American organization which establishes that the most powerful shall park closest. All of the lots had been color-coded into a hierarchical caste system. Blue, of course, was best. At Texas Stadium, as elsewhere in life, there is a bit of difficulty in sorting the populace into their proper and appropriate stations. It took a large number of policemen and stadium personnel to channel the flotilla of automobiles into the right harbor. After parking was finally accomplished, there remained the problem of finding the correct gate.

We had it lucky. Upon alighting from our car, we were fortunate to spy Howard Cosell just ahead of us. Because we had press passes, we hurried to walk along behind him. We felt that if anybody could find the press gate, it would have to be Howard.

As it turned out, we got through the gate before Cosell, for, just as he was approaching it, a man wearing a Stetson and boots caught sight of him and called out loudly, “Hey, Howard,” he said, “I want you to meet my boy.” Patiently, with a very genial smile, Cosell turned to shake the offered hands. Before he could pass through the gate, a plump lady in a purple polyester pantsuit and a beehive hairdo, ran up to him and said something, giggling madly all the while. Just beyond, her similarly attired friend jumped up and down shrieking, “Ohhh, she’s SPEAKING to him. Didcha SEE it? She SPOKE to him! Ohhh!!” The audacious lady in purple returned to her friend, swinging her wide hips in a jaunty celebration of her intrepid foray into the land of the celebrated. “I TOLE you I was gonna do it,” she smirked proudly. “I TOLE you!” “Ohhh,” squealed her friend, “you’re just TOO MUCH.”

Since my companion and I did not suffer the impediments of fame, we passed through the gate without handshake or greeting and soon found ourselves waiting outside the press elevator. This was obviously a very special elevator, since riding it required a ticket which was claimed by a uniformed guard. The elevator served both the press and those persons of wealth and privilege who owned the boxes on the second tier of the Stadium. Any person, place, or thing possessing $50,000 may use that amount to purchase revenue bonds from the community of Irving, which, technically, owns the stadium. Such a purchase grants one a box composed of cement floors and sheetrock walls. Comfort is not included in the $50,000 price tag. It must be purchased separately and, it is said, can cost as much as an additional $100,000.

By the time the friendly armed guard had waved us onto the elevator, and we were crushed against its back wall by well-dressed, gray-haired men smelling of expensive talc, I was already feeling what Don Meredith was to mention in his television introduction later that evening.

“Here we are in Texas Stadium,” Meredith said, “which some people call the finest football facility in the world and others call a vulgar display of wealth.”

According to one of the television crew, waiters rode this elevator, too. He related an incident that occured when he was riding from the basement level with two young blacks dressed in waiters’ uniforms. The elevator stopped at the first floor to pick up a couple of flushed and jovial football patrons. (Anybody who pays more than $50,000 for a box deserves to be called something more prestigious than football fan.) Greeting the waiters with hearty backslaps and conviviality fueled from the plastic cups they carried, one said, “We’re gonna have us one good time, aren’t we, boys?”

The waiters tried to push through this rush of congeniality with an evenly-announced, “Coming out, please.” Perplexed, one patron responded loudly, “Wait a minute, boys. This is the wrong floor. The boxes are on the second floor.”

The taller of the two waiters gave the patron a long, cool glance as he replied, “First floor is where the slaves get off.”

The corridor that leads from the elevator to the boxes is like a carpeted hallway in a very long motel. During the trek to the press booth, I craned my neck to see inside any box which had an open door. I wanted to know just how much comfort $100,000 would buy.

One open doorway was partially blocked by a fiftyish matron in an expensive blue cocktail suit.

“Honey,” she was calling to her friend, “you must come and see this. It is simply darling!”

Her friend, also in expensive blue, joined her in the doorway.

“Now why didn’t I think of that!” she moaned. “It’s such a cute idea—decorating for Halloween.”

Over her shoulder I could see the orange and black crepe paper streamers that stretched from wall to wall and the witches and pumpkins that dangled from the ceiling. The decorating effect was that of a high-school gym prepared for a sock hop.

A bespectacled young man from the Detroit Lions staff joined us as we traipsed noiselessly along the endless curving hall in search of Press Box A. Behind the dark frames of his glasses, his eyes were large circles of wonderment.

“I can’t believe this,” he said, shaking his head in amazement.

“Not exactly like Detroit, is it?” my companion remarked drily.

The visitor was too stunned to hear. “What goes on down here in Texas anyway?” he asked, rhetorically.

Through an open door we glimpsed a buffet table laden with silver dishes and centered by a large silver urn full of grapes. Manicured middle-aged gentlemen in business suits stood around in small, chatting groups, sipping from glasses supplied by a whitecoated bartender. Scattered here and there were a few strikingly pretty girls in miniskirts and tall boots.

The young man from Detroit shook his head slowly. “You have to see it to believe it,” he said softly.

Since we had not yet found our destination, we stopped a friendly looking man wearing a badge that said CATERER.

“Could you direct us to Press Booth A?” my companion asked.

The lanky informant squinted and inquired, “Is that the booth for working press or the one for television people?”

My escort, a writer for television, managed to respond in a fairly normal tone that we sought the television booth.

“Then keep straight ahead,” the helpful guide instructed. “You can’t miss it ’cause its just across from where the real press sits.”

The TV/Radio Press Lounge was large and spacious. A number of people were sitting at the round tables, eating, drinking, and watching giant TV sets. Our booth opened off the lounge. It was a small room furnished with comfortable chrome and leather swivel chairs lined in front of a counter which ran the length of the far wall. Above the counter the wall was open to the air. A moth fluttered into the room and wavered with surprise before weaving his way back out toward the center of the stadium. Like the moth, I felt a little confused by my surroundings. I reached out through the opening and felt the hot, humid air on my skin.

“What a strange place this is,” I remarked, looking from our partially open room to the partially-covered roof. Through the gaping hole over the playing field, the dingy clouds looked like fuzzy balls of lint. “It’s like being inside and outside at the same time.”

“Yeah,” an inhabitant of the booth remarked drily, his shirt sleeves rolled up because of the heat, “this stadium lets you enjoy the worst of both worlds.”

Free food, free drinks, free transportation and free information kits were available for the press, courtesy of the Dallas Cowboy organization. Drinks were brought by a pretty girl in a movie-musical cowgirl costume. Fortified, we settled back in our swivel seats to await the beginning of the game.

On the field, a group of young boys were involved in a punt, pass, and kick competition. The computer-operated billboard flashed a steady stream of electronic enthusiasm and advertisements while the public address system showered the crowd with carefully-enunciated information.

“Here are the latest standings in the Oak Farms Dairies Favorite Cowboy Contest,” the announcer said. “First in the standings is . . . ROGER STAUBACH!”

The Honors List was not quite as long as that announced by the British in celebration of the Queen’s Birthday, but it was impressive. One by one the announcer recited to the lukewarm applause of the crowd. There was the Zale’s Jewelry Unsung Hero Award, Ken’s Men’s Shop’s Big Play Award, Oak Farms Dairies Most Valuable Player Award and Tiche’s Department Store’s Mascot-of-the-Week Award.

Last, but not least, was the Game Ball Recipient Award . . . a complete set of Encyclopedia Brittannica.

The scoreboard cheered fervently.

The band of paunchy musicians dressed in cowboy garb broke into a loud rendition of the rock tune, “Joy to the World,” and the cheerleaders employed by the Cowboy organization danced onto the field. Selected from a crowd of young hopefuls, the girls had at first actually tried leading yells, but this didn’t work out. Now they simply danced.

Some of the men in the booth were sharing binoculars for a closer examination of the cheerleaders. “When they were looking for a name for the girls, I suggested calling them The Tight Ends,” one man snickered.

An American flag appeared on the scoreboard and everybody stood up. Down on the bright green field, a trumpeter played the national anthem while the lights on the scoreboard simulated a waving flag, and the cloth flag on the field hung limp and motionless in the heavy air.

As the players dashed onto the field, the television monitor came alive with the opening titles for ABC’s Monday Night Football telecast. It was time for the game and Meredith’s work to begin. In a van far beneath us Chet Forte began to peer at his monitor. Down there on the plastic grass, 22 men gathered to play while 65,378 throats roared approval and a nation of eyes sat watching, waiting to see those 22 bodies lunging, thudding, jarring, throwing, catching, running across the vivid, unnatural green.

Early in the game, the Cowboys took command with two touchdowns. One of the men from ABC fretted that the game was going to be too one-sided. “I want Dallas to win,” he explained, “but it’s got to be even and close. Otherwise they’ll be dial-clicking all over the place.” Before the first half was over, the Lions had narrowed the point gap. “That Greg Landry is a good quarterback,” the ABC employee said happily.

During the half-time, the field bloomed with dancers, twirlers, bands. Everywhere there were flashing feet, flashing horns, flashing batons, and flashing legs. While the scoreboard recited statistics, the sweet-faced cowgirl brought refreshments. The Governor of Texas was introduced and booed. On the television set Howard Cosell was narrating highlights of Sunday’s games while everybody waited for the 22 heroes to return to their carpeted battleground.

The stifling clouds that hung over the stadium, smothering the air with a sticky heat, finally began to spill over during the second half. With the first drops, the cameramen hastily began to cover their equipment with plastic. Gradually the rain grew heavier until it poured through the funnel-like opening in the center of the stadium. Under the roof that protected them, the dry spectators sat watching as the torrent of water fell upon the players and turned the surface beneath their feet into a slick sponge.

The game surged on, the players fighting for the ball, for time, for points, for annihilation of other players, for yardage, for winning, for money, fame, glory, TV cameras, Super Bowl rings, commercial endorsements, and a set of Encyclopedia Britannica.

Dallas scored and the scoreboard erupted with stars, rockets, hosannas. Detroit scored and the scoreboard flashed the single word—Touchdown.

“I can remember when scoreboards were incapable of editorializing,” somebody mused.

“That was a long time ago,” another responded ruefully.

The cold, drenching rain had stirred and cooled the air, making our little room more comfortable. On the TV set, the cameras panned from the wet field to a view of the sheltered boxes, while Don Meredith’s Texas drawl commented, “The players refer to those people up there as The Romans.”

Out in the rain the game was snarling and thudding toward its end when a wet, tired player suddenly began striking out furiously at everybody in sight. A player from the opposing team lifted him from behind and carried him away from the other players, his angry fists still nailing the air. The buzzer sounded, ending the game. Dallas had won, 27 to 24.

We tramped through the chilling rain to find the car, then inched precariously along the highway in the midst of a sluggish glut of traffic. In our rented car neither the heater nor the defroster worked. Cold and wet, we sought refuge in a motel coffee shop where I huddled over a cup of hot tea offered by a kindly member of the television crew. “What did you think of your first pro football game?” he asked.

I hesitated, searching for the answer among the bulky images that crowded my mind: rows of expensive equipment lining a tier at Texas Stadium, thousands upon thousands of people shouting with one voice, twenty-million television sets linked into one control truck, Don Meredith wearing earphones instead of a football helmet . . .

I smiled at the crewman and took a sip of tea. What do you say about a phenomenon that is part ritual, part business, part entertainment, part craft, part violence and dexterity, part passion and mystery? Something Don Meredith had said crept into my mind: “You have to remember that, basically, it’s only a game . . .”

Sherry Kafka lives in San Antonio. She first encountered Don Meredith when he was writing articles for The Dallas Morning News on his trip to Europe as a college student.

- More About:

- Sports

- Film & TV

- TM Classics

- Television

- NFL

- Longreads

- Football

- Larry McMurtry