On June 1, 1844, Captain Jack Hays led fourteen Texas Rangers from their camp on the Medina River twelve miles west of San Antonio. They rode north through broken hills and winding streams in search of American Indians. What happened one week later, on a small creek about fifty miles away, would dramatically change the nature of frontier combat and the history of Texas and the American West.

For most of the previous year, the western half of the young Republic of Texas—where most Indian attacks occurred—had been relatively quiet. When President Sam Houston had been elected for a second time, in 1841, he’d sought to solve the nation’s conflicts diplomatically. The main reason was money. Between the Indians incensed at white settlers encroaching on their land, and Mexico, which had never acknowledged the independence of its former territory, the cash-strapped Republic faced hostility on multiple fronts, and it was incapable of properly defending against incursions. Mexico had its own problems to deal with—lack of money and troops, as well as internal strife—that kept it from causing too much trouble for the new republic. But Indian attacks were taking their toll. Houston’s efforts to treat with the Indians had achieved some success: during meetings in March and September of 1843, Texas had signed agreements with several of the smaller tribes. They discussed a boundary line beyond which the Indians would remain, but because the largest and most powerful tribe in Texas, the Comanches, had attended neither meeting, the line and its exact location would have to wait until the third, which convened in April 1844 and was still in session as Hays’s Rangers broke camp.

Texas’s cost-cutting measures had included disbanding the 560-man regular army and auctioning off the navy’s four vessels, which left Hays’s 40-man Ranger company as the country’s only defense force. Lately, they had spent more time chasing Texan outlaws, Mexican spies, and bandits along the Rio Grande than fighting Indians.

Because of the ongoing negotiations, Hays was under orders not to penetrate too far into Indian country. But a series of raids had recently been perpetrated on the San Antonio area, and the dutiful captain had gathered nearly half his company and headed north in search of the culprits. After several days with no success, they turned toward home.

At midday on June 8, they took a break on a creek a few miles north of the Guadalupe River, near the Pinta Trace, an old north-south trail. Two men climbed a nearby cypress tree to collect honey from a large bee colony. They had just begun to cut into the tree when the Rangers’ rear guard galloped into camp. They had sighted ten warriors on the back trail, heading their way. The honey was forgotten, and Hays ordered his men to mount and prepare for a fight.

The Indians came into view—warriors all, sporting full war paint and armed with lances, bows, and shields. A raiding party, Hays was sure. The fifteen Rangers tightened their horses’ cinches, mounted, checked their arms, and moved forward slowly. The Indians retreated, also slowly. As they fell back toward thicker brush and trees, the Indians pranced about, clearly hoping to lure the Rangers into attacking. Hays resisted this trap, and the Indians disappeared into the trees. Moments later they reappeared on a hill behind the brush. Now there were between sixty and seventy of them—Comanches, it looked like—dismounting and taunting the Rangers, yelling, “Charge! Charge!” and daring them to fire their rifles. The odds had shifted: the Rangers were outnumbered four to one by a Comanche war party.

This gave Hays little pause. The Rangers with him were a hardened bunch, the best he’d ever had. Almost all had served with him before, and the new men were good, especially quiet Samuel Walker, recently escaped from Mexico.

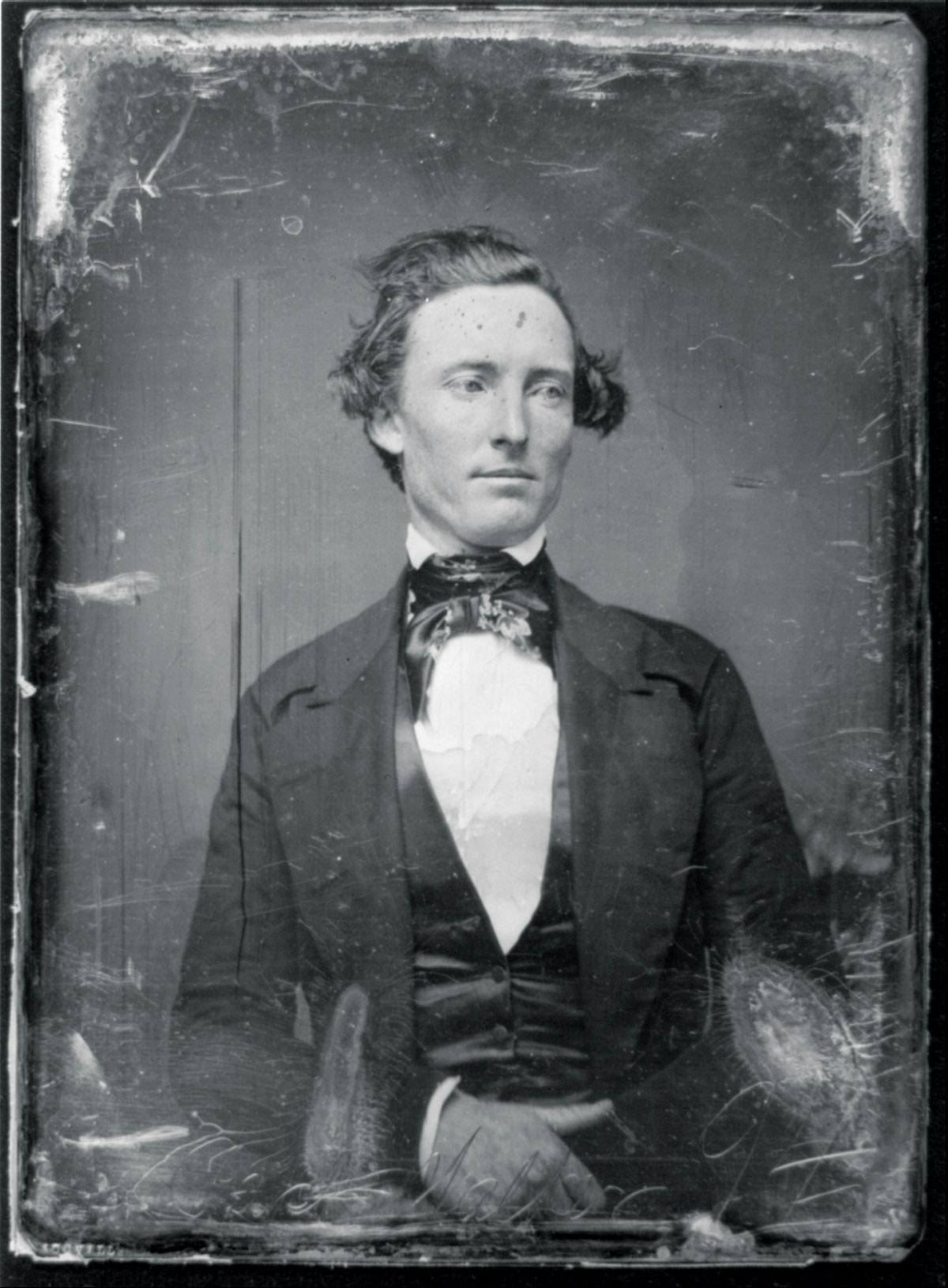

Walker didn’t resemble the other Rangers, most of whom were large, bearded, and rough. He was slightly built, and beardless, with sandy reddish hair and an easygoing demeanor. Born in 1815 into a large Maryland farming family, he had been apprenticed as a young man to a carpenter. It didn’t take—Sam later admitted to being “naturally fond of military glory,” with a “love of chivalric immortal fame”—so he had enlisted in the Army to fight in the Creek and Seminole Wars. Though promoted to corporal for bravery, he had found that the life of an enlisted man wasn’t for him. After some railroad work in Florida, he’d headed west and arrived in Texas early in 1842.

Walker had signed up for ranging work in time for the Battle of Salado Creek in September, where he helped repel an attack by more than a thousand Mexican soldados. After the battle, seven hundred Texans, including Walker, had reorganized to march into Mexico in retaliation. They recaptured the towns of Laredo and Guerrero and then were ordered to disband and return home. Most did, but three hundred men marched on the Rio Grande town of Mier, unaware that three thousand Mexican soldiers were in the area. They were ultimately forced to surrender, and the survivors were marched to Mexico City. General Santa Anna ordered their execution but eventually mandated that only every tenth prisoner from the Mier expedition would be killed. Though Walker survived, he was imprisoned and brutally beaten. After six months, he escaped. In September 1843 he returned to Texas, and he joined Hays’s Ranger company in February 1844.

Hays had worked his men in horsemanship and marksmanship, using Indian and vaquero riding tactics and equipment—like a heavier Mexican bit that provided more control to the rider, allowing him freedom to deal with his firearms—and drilling them constantly until they rivaled the Comanches themselves. And they were a disciplined group, or as disciplined as a group of Texans could get. As he faced the Comanche war party that day in June 1844, Hays knew what his men were capable of, and he knew he could count on them.

A year earlier, Hays might have declined the Comanches’ invitation for a fight. But this time was different. This time the Texans had a new weapon.

The standard frontier gun at the time was the mountain or plains rifle, a more compact version of the Pennsylvania-Kentucky flintlock muzzle loader, accurate to about two hundred yards. Dependable and powerful, it had one drawback: it took time to properly load—a full minute or close to it, and even longer on a horse, in a fight. Indians knew this and adjusted their tactics accordingly. They would send a few warriors to draw fire; then the entire band would swoop down onto the furiously reloading Anglos. Carrying a pistol or two or three helped, but these single-shot flintlocks were inaccurate at anything but the closest range, and they often snapped, or refused to fire, because of wet powder. And since an Indian could shoot ten to twelve arrows in the time it took to reload, the Anglos were at a serious disadvantage. Until now.

On this day, Hays and his men were armed with Samuel Colt’s patented revolvers, a newfangled invention they had only recently obtained.

A Connecticut Yankee who had been raised in a family of some privilege—at least before his father lost the bulk of his fortune—Colt had been fascinated with explosives and firearms since childhood. He’d come up with the idea for his revolver while still in his teens, but he didn’t have the funds for such an undertaking, so he’d hit the road for a few years as the Celebrated Dr. Coult, putting on stage shows demonstrating the wonders of laughing gas. Besides being smart and mechanically curious, Colt was a born huckster, and these shows were popular and lucrative.

Much later, Colt would write that he burned with a desire to do “what never before has been accomplished by man.” Toward that end, in 1836, at the age of 22, after he’d saved enough money and acquired several investors, and after years of experimenting, he patented a five-shot revolver. The new pistol took advantage of a recent innovation, the percussion cap, which had replaced the flintlock as a much more reliable way to ignite gunpowder. He began manufacturing the guns in a Paterson, New Jersey, factory. Firing five shots in less time than one man could reload a flintlock weapon should have guaranteed large orders from the government. But the Paterson, as Colt’s first revolver became known, was fragile and fired a small-caliber ball, and it had to be half-disassembled to reload, so military tests were unimpressive, as were sales. When his company went bankrupt in 1842, Colt had turned to other pursuits, such as underwater mines and waterproof cables.

But before Colt went out of business, his best customer had been the Republic of Texas. Paterson revolvers had somehow found their way there, and the Texas army and navy placed orders for the expensive weapons. When the two military branches were eliminated, many of the five-shooters were given to the Rangers. They had used the Colts in fights before June 1844, but it was only recently that all men were armed with revolvers in addition to their flintlock guns. Hays had seen enough to know what the revolver could do. And as he looked up at the large force of belligerent Comanches before them that June day, he might have been itching to test its worth in combat against a formidable enemy. He ordered his small company forward.

Reaching the base of the peak and realizing they were out of sight of the Comanches, Hays quickly led his men around the hill and up one side. As the surprised Indians leaped onto their mounts, the Rangers fired their rifles, pulled their five-shooters, and charged into them, shooting left and right. The Comanches gave way but regrouped and closed around the Rangers, who formed a tight circle, backs to one another, and for fifteen minutes the battle raged at close quarters in a blizzard of arrows, lances, and pistol rounds. Two Rangers were hit with arrows, and lances found two others, Sam Walker and Ad Gillespie. But at such a short distance, the Patersons found their marks, and Comanches fell to the ground steadily until they finally broke—shocked, surely, by the guns that never seemed to stop firing—and hurtled off the hill.

The Rangers paused to change cylinders—another five rounds each—and pursued. The running fight continued for two or three miles, the Comanches wheeling and charging a few times, the Rangers meeting them and forcing them steadily back. A half hour later, about forty Comanches still resisted. The Rangers were down to their last shots. When Hays saw a chief exhorting his warriors to charge, he asked who had a loaded rifle. The wounded Gillespie did. “Dismount and shoot the chief,” Hays said. Gillespie dismounted, took careful aim over his saddle, and fired. The Comanche leader fell from his horse, dead, and the rest finally galloped away.

The Rangers counted 23 dead warriors, among them a few Mexicans. Their own casualties were 1 man dead and 4 wounded, Walker the most seriously—some expected him to die, though he would eventually recover. Hays sent a rider to San Antonio for help and supplies. By the time Hays and his men returned home, news of the battle had already begun to circulate. Hays would name the stream where the battle started Walker’s Creek, and he told a few people about the epic fight there. Texas newspapers ran an account, but almost no one understood its significance: never again would Indians own the clear advantage, man to man, in an evenly matched fight.

A year later, with annexation imminent, U.S. President James Polk ordered Army regulars into Texas under the command of General Zachary Taylor. By July 1845, 1,300 troops were camped on the beach at Corpus Christi, just 130 miles up the coast from Mexico. When Taylor requested locals who knew the area to act as scouts, large groups of eager Rangers signed up. Like many Texans, they felt they had a score to settle with Mexico for what they considered unwarranted executions at the Alamo and Goliad and during the Mier expedition. Walker, who had vowed to avenge his executed Mier comrades, volunteered.

Early in 1846, when Taylor and his regulars were ordered to move to the mouth of the Rio Grande, across from Matamoros, Walker’s 26-man company was mustered in for three months. They immediately began to do what Rangers did best: scout and reconnoiter through hard country and fight like devils when necessary—but only after Walker requisitioned and received Colt Patersons for his men. As skirmishes with the Mexican army began, and war became official in April, Walker and his Texans were in the thick of it, and the value of skilled horsemen who knew the land and how to operate in it became clear quickly. Over the next few months, they earned a reputation for getting the job done, no matter how difficult, sometimes slipping into Mexican camps and towns to engage in reconnaissance. Walker’s personal deeds especially—delivering valuable information through dangerous country, twice making his way through enemy territory bearing critical dispatches—made headlines across the United States. He earned further glory in battles at Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma. In a matter of months, his daring exploits made “the gallant Walker” the first true hero of the Mexican-American War.

Walker’s enlistment was soon up, and that summer, when two regiments of Texas mounted volunteers, many of them ex-Rangers, were raised, Hays was elected colonel of one, with Walker as his lieutenant colonel. In September, in the hard-fought Battle of Monterrey, the Texans took the lead in assaulting the city, with Hays and Walker at their front. When Taylor arranged an armistice on September 24 that allowed the Mexican army to evacuate the city with their arms, the Texans were furious—“unsated with slaughter,” wrote one observer. In Taylor’s eyes, the Texans’ excellence in combat barely offset their insubordinate, unruly behavior—and the occasional vindictive atrocities they had visited on Mexican citizens—so he ordered them home when their three-month enlistments expired.

Few outside Texas had heard of the Rangers, but newspapermen delighted in reporting the adventures of the colorful volunteers with their own style of fighting. Walker quickly became the best known. Several Army officers had petitioned Polk to offer him a commission, but when the president did so, Walker didn’t accept immediately—possibly weighing his unpleasant experiences with the Army in Florida against regular pay and a captaincy and another chance at vengeance in Mexico. But on October 1, 1846, he became Captain Walker of the newly formed U.S. Regiment of Mounted Riflemen and was ordered to report to Washington to begin recruiting his company.

The Army’s leadership hoped that Walker’s popularity would induce young men eager for glory to enlist under his command, especially because the war was unpopular in the North. Walker traveled to New Orleans, where he sailed for the capital, and then New York for a brief visit. At almost every stop, he mentioned that he wanted Colt revolvers for his men. The problem was, there were none. Due to lack of sales, Samuel Colt’s company had gone bankrupt a few years before.

Though he had no money and no factory, Colt hadn’t given up on his revolvers. He’d continued his attempts to garner contracts and interest in his guns. When he learned that Walker was now in New York, a desperate Colt saw his opportunity. He wrote Walker, asking to meet and requesting a list of actions in which his pistols had been used. He also urged the Texan to intervene personally with the president and the secretary of war to push for a military contract with Colt.

Walker replied immediately. He praised the Paterson in the highest terms: the Texans’ “confidence in them is unbounded,” he wrote, “so much so that they are willing to engage four times their number.” He went on to describe the June 1844 fight—characteristically, without mentioning that he had been there—and gave all the credit to Colt’s pistols. “With improvements,” he concluded, “I think they can be rendered the most perfect weapons in the world for light mounted troops.”

Colt seized his chance. If anyone could get him a sizable contract, it was Walker, who somehow had obtained permission to act as a buying agent for the government. They met the next day.

They were very different men. Colt was loud and self-promoting; Walker was quiet and self-effacing. Colt enjoyed the pleasures of the good life, including fine whiskey and women; Walker was accustomed to a bedroll on the ground. But they got along swimmingly, and a friendship grew as they corresponded. (Walker once referred to Colt as Peace Maker, a name that would be applied to a future Colt firearm.) In that first meeting, they discussed how the Paterson could be improved. Walker had some very specific changes he wanted to see—changes that would result in a sturdier, larger, more powerful gun.

In a letter the next day, Colt agreed to deliver one thousand revolvers in three months. He had to know that was an impossible delivery date for a new, untested pistol, but Walker wanted them as soon as possible, before he left for Mexico. In further meetings, they agreed on the improvements he wanted, and they were many: a larger cylinder to accommodate six .44-caliber conical or round balls and hefty powder charges; a much-needed trigger guard; a nine-inch barrel for improved accuracy; fewer moving parts; and simpler, faster reloading. Walker even specified the kind and quality of metal (“the best cast or double sheet steel . . . the front sight of German silver”) for each part.

Colt wasted no time getting to work. Walker used his high-placed contacts—the president, the secretary of war, and Senator Sam Houston, to name a few—to push the order through, and the two signed a contract. Fortunately, Colt had retained the patents to his firearms, so after cajoling a friend, armsmaker Eli Whitney Jr., into taking on the manufacturing, he was back in the revolver business. At Whitney’s Connecticut factory, Colt hired fifty experienced men and paid them up to four times the going rate. He begged, blustered, and borrowed, but he got the order filled, though it took six months, not three. He dubbed the new gun the Colt Walker—in gratitude, surely, but also in calculation, since Walker’s name could only improve sales.

But Walker’s men would never receive their revolvers. Some four hundred did reach Hays and his Texas regiment before the hostilities ceased, and the huge pistols impressed everyone who saw them in action, including high-ranking Army officers: “No weapon is equal to it,” said one brigadier general. Before the war was over, the Army ordered a thousand more, and additional orders started pouring in—not only from the U.S. military but from countries around the world wanting the gun that could shoot six times without reloading and possessed the range and stopping power of a rifle. The Crimean War, the California Gold Rush, the escalating Indian wars, the dangerous trek west by countless settlers—these developments all contributed to a boom in the weapons market, and for many years, Colt’s weapons were the most desirable. He built a large plant in Hartford and began making high-quality guns—and a fortune—using interchangeable parts and one of the earliest assembly lines.

There were slight imperfections in the Colt Walker—the loading lever would not stay in place, and the heavy powder load sometimes burst a cylinder—but after that first batch was shipped, each subsequent generation of Colt revolvers included improvements, and each became a huge success. Several models were adopted as the standard sidearm for U.S. military officers. The 1873 Single Action Army Peacemaker, Colt’s first revolver using the new metal cartridges, would become known as the “Gun that Won the West,” carried by settlers, lawmen, outlaws, Indians, miners, and countless others who never ventured ten miles from the East Coast.

Samuel Colt didn’t live long enough to see the Peacemaker. He died in 1862 of gout and rheumatoid arthritis, at the age of 47, one of the richest, most famous men in America, with his beautiful young wife and three-year-old son at his bedside. He’d achieved what he set out to do—“what never before has been accomplished by man.” His widow and her brother took over the business and guided it well for the next 39 years.

Samuel Walker got what he wanted, too—military glory, and even a measure of immortality. Though they had only flintlock pistols to use, his company reached Mexico in May 1847, and his young volunteers spent months distinguishing themselves in the unglamorous job of keeping General Winfield Scott’s supply lines open on the march to Mexico City. Once, fifty of Walker’s men repulsed an attack by six hundred Mexican lancers, with their captain walking behind them and maintaining discipline with his coolness under fire. By the middle of September, American forces were in command of the capital. But Santa Anna had begun one final counteroffensive. Part of his plan was to cut off Scott’s army from the coast, and in early October, a U.S. column set out from Perote to Puebla, eighty miles away, with Walker’s mounted company and two others as escort. On October 9, word reached them that Santa Anna and his lancers were in Huamantla, a town eleven miles away. Walker, given command of the two hundred mounted men, was sent ahead to reconnoiter while the main column followed.

Four days earlier, Walker had finally received two of the revolvers named after him, a presentation pair from Colt sent months before. Each of the massive guns weighed almost five pounds fully loaded and charged, but they would fit in the large saddle holsters Walker had arranged to have made for his company. On the cylinder was engraved a scene representing the Battle of Walker’s Creek. Colt had asked the captain for a drawing of it to give to his engraver, though it’s doubtful if Walker ever supplied it, since the Rangers in the engraving wore U.S. Army uniforms. But it was a fitting tribute to those who had made Colt’s reputation.

Walker’s horsemen reached the outskirts of Huamantla at noon to find several hundred lancers waiting for them. Inside the town, Santa Anna’s artillery was preparing to leave. Walker led his men in a charge into the enemy ranks, and the Mexicans wavered and then broke, turning and retreating into town, the U.S. volunteers at their heels. The Mexican cavalry scattered, and Walker took command of the main plaza. He’d just sent scouting parties out when all two thousand of Santa Anna’s lancers descended on the town. In the fierce fighting that followed—a battle that would trigger a vengeful bloodbath on the town after the main U.S. column arrived and routed the Mexican troops—Walker was shot from behind in the back and head. He died minutes later, blood streaming down his face, but not before telling his men, according to one soldier, “I am gone, boys. Never surrender! Never surrender! Hand me my six-shooter!”