Welcome to our Vintage Postcards of Texas series. Each week, we’ll take you through the history behind a vintage Texas postcard: the history of the place, some background on who sent or received that particular missive, and, of course, what the location looks like today.

With the state fair in grease-popping high gear and the Texas Longhorns and Oklahoma Sooners teeing it up in the Cotton Bowl on Saturday morning, this week’s postcard of the Music Hall at Fair Park in Dallas feels especially fitting. Back when Reed Robinson, who lived on Wentworth Street in Houston, received the card from the mysterious “Moo Moo,” it was known as Fair Park Auditorium. Postmarked September 28, 1953, the message reads:

Hi Reed. [Illegible] I wait here in Dallas from 2:30 AM to 7 AM, then to Witchita [sic] Falls. Shorter time there but get in Lawton same time. This is where we played when we were here last — Moo Moo.

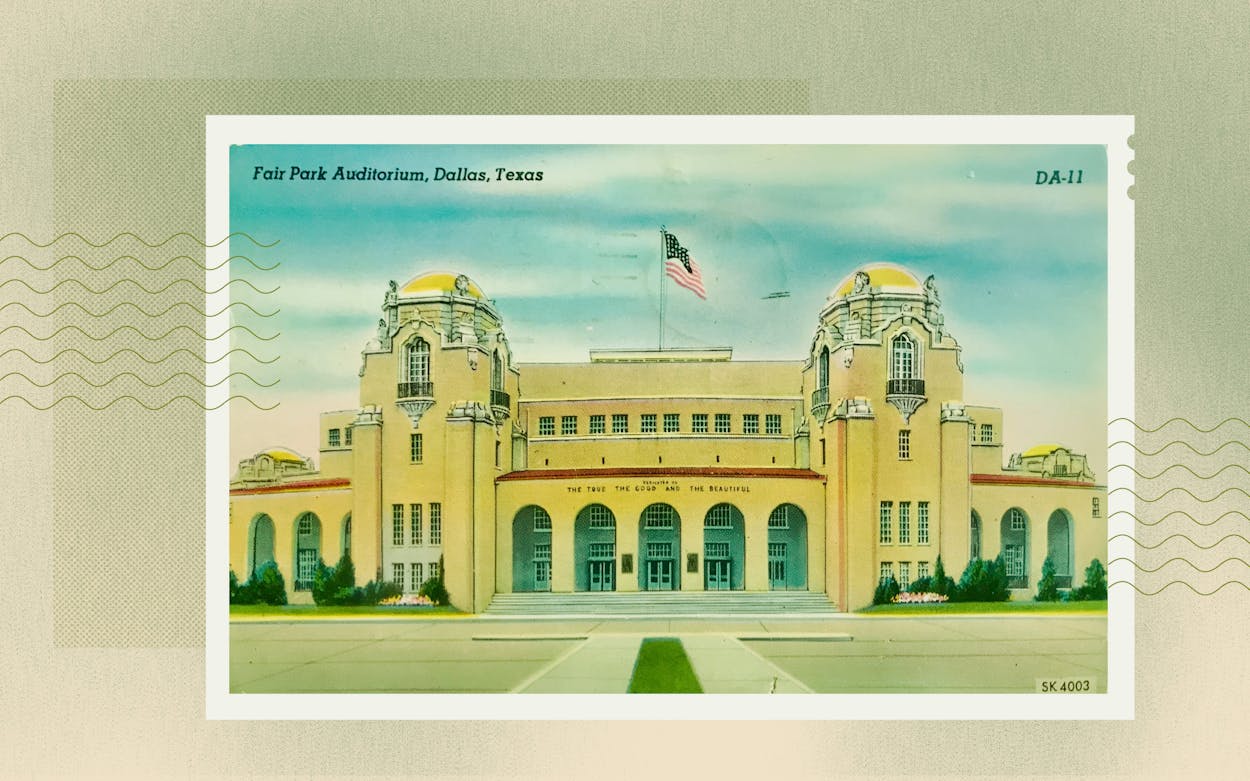

The Fair Park Auditorium opened at 1 p.m. on October 10, 1925, the opening day of that year’s State Fair, with a legend over the arched entryways reading “Dedicated to the True the Good and the Beautiful.” Early bookings included a group called the De Reszke Singers, who appeared with comedian and vaudeville performer Will Rogers.

During the Texas Centennial Exhibition in 1936, the Spanish colonial edifice served as a showroom for General Motors. Over the years, the venue has hosted traveling musicals, ballets, and orchestras, as well as homegrown performers (apparently including Moo Moo, author of the postcard, who wrote to Robinson that he or she played at the Music Hall). It was home to the Dallas Opera from 1957 to 2009, and shortly after the building was air-conditioned in 1951, the Dallas-based Starlight Operettas moved out of the nearby open-air Fair Park Bandshell and into the building, which by then was known as the Music Hall at Fair Park. The company, now known as Dallas Summer Musicals, still calls it home.

The late sixties brought wilder and woollier shows, as “the true, the good, and the beautiful” was electrified and amplified. ZZ Top opened for Jimi Hendrix there in 1968. Cream, Eric Clapton’s blues-rock power trio, performed there later that year, and Led Zeppelin rumbled through in 1969. Since then, its stage has featured artists from Bob Dylan to Bette Midler to R. Kelly.

The building was remodeled in 1972, with an overhaul of the facade that’s anything but sympathetic to the original building.

Outside the walls of the music hall, the wider Fair Park grounds have a tangled racial history.

In 1953, the year this postcard was sent, the State Fair announced that African-Americans could henceforth pay to enter the State Fair grounds on any day they chose, but they were still only welcome on the rides on “Negro Achievement Day.” That half-measure led to protests: African-Americans organized a boycott and picketed the festival, carrying signs with messages like “Today Is Negro Appeasement Day at the Fair” and “Don’t Sell Your Pride for a Segregated Ride.”

These protests took place in the midst of an uneven path toward integration in Dallas. A few weeks after Moo Moo’s postcard was sent, Bud Wilkinson’s Sooners defeated the Longhorns 19-14 in the Cotton Bowl, a quarter mile away from Fair Park. It marked their fifth triumph in six years, with another four in a row to come, but it would be three more years before Oklahoma would integrate their football team. Texas would not have a black letterman until 1970, when the recently deceased Julius Whittier entrenched himself in the starting lineup for the first of three years.

The story of Fair Park remained inextricably intertwined with race over the years. In 1966, the State Fair committee hired a consultant in response to research showing that white attendees felt scared by seeing African-Americans as they made their way to the fair, as reported in the Dallas Observer. The surrounding neighborhoods should be “bought up and turned into a paved, lighted, fenced parking lot,” recommended the consultant. “If the poor Negroes in their shacks cannot be seen, all the guilt feeling revealed above will disappear, or at least be removed from primary consideration.” Afterward, Dallas mayor Erik Jonsson used eminent domain to replace apartments and homes owned by African-American families with parking lots surrounded by fences, a reshaping of the neighborhood that affects it to this day.