The fish would be airborne for only a few seconds, but to the hypnotized eyes of a human observer time slowed down, and the sight lingered for so long it could almost be studied like a painting, every detail seared into memory. Maddened by the hook in its bony jaw, the creature would explode out of the water, a twisting, shuddering muscle rocket perhaps six feet long, perhaps two hundred pounds, its massive silver scales shimmering brilliantly in the summer sun. The fish would thrash its head so desperately and violently it seemed that it might break its neck; its gills would heave open and then close with such force that they produced a sound that one fisherman likened to the clatter of giant castanets.

“The wild glory of the sea,” a nineteenth-century writer with the delightfully robust name of Henry Wellington Wack described the fish. “He is a battle flotilla in full blazing armor, and peace and good will are not in him for an instant.”

The fish was the tarpon, known to spellbound fishermen as the silver king. Only a decade or so after the first tarpon was caught on rod and reel, in Florida in 1885, a barren settlement of one hundred or so people on the northern end of Texas’s Mustang Island changed its name from Ropesville to Tarpon and set itself up as a destination for sportsmen from all over the country, who came by the thousands for a try at what one writer described as “the most beautiful creature that lived.”

The town changed its name again in 1910, to Port Aransas, an aspirational designation for a place with plans to become a major seaport. But it was nearby Corpus Christi, which opened a ship channel in 1926, that ended up being the seaport—and Port Aransas had to settle for proclaiming itself, with some justification, the Tarpon Capital of the World. It was still a small village with only a few hundred residents, a lonely end-of-the-earth place where the ocean waves washed up mahogany logs from distant shores and prehistoric camel teeth from buried Pleistocene reefs. One of the village’s few architectural landmarks was the Tarpon Inn, where in the days before motorboats, fishing guides met clients for breakfast before rowing them in skiffs through the pass that led between the barrier islands to the open gulf. Once around the jetties, they trolled along the surf line, where they were almost certain to find immense schools of tarpon swimming in the deep guts between the shallow sandbars where the waves crested and broke.

“Nothing but solid tarpon traveling north and rolling everywhere,” Bubba Milina recalled. “Hundreds of ’em breaking the water at the same time.”

Milina is one of the last of the great fishing guides from the mid-century era when Port Aransas was still the tarpon capital. When Milina and his generation began to guide, in the thirties and forties, it was no longer necessary for anybody to row into the Gulf. Instead they used tough little Farley boats, 22 or 26 feet long, built on the island out of cypress or mahogany, with inboard motors and high fluted bows designed to surge through the choppy inshore waves.

“They was the most spectacular jumping fish there is,” Milina told me. At 93, he’s a powerful-looking man with a barking voice. We were talking on a winter morning in Port Aransas, in the bedroom of the house on South Ninth Street that he and his late wife, Woodie Raye (“She caught a few tarpon in her time!”), had built by hand. A bundle of four or five rods and reels stood upright in the corner. On the wall next to the bed was a picture of Milina and Woodie Raye when they were young, posing on a local dock.

Milina would usually take his clients to the traditional hunting grounds beyond the mouth of the jetties (the same jetties that his father, a Yugoslavian immigrant, had helped build in the early part of the century). Catching a tarpon, or at least hooking one, was almost a given. Milina would typically slip around the apron of submerged rocks at the end of the north jetty and work the surf along San Jose Island. It wouldn’t be long before he’d find a school of tarpon, in the second or third gut. They might be “rolling,” idling about near the surface, taking in air through their open mouths, or they might be actively swimming, either in pursuit of prey or on a single-minded migratory agenda.

“And then you’d start moving north, and you’d intercept another bunch, and then a little farther bit up the line, you’d intercept another bunch. You might have a school of tarpon a hundred yards wide and a goddam four or five hundred yards long.”

Nowadays the starkest record of the glory years of the silver kings can be found in the lobby of the Tarpon Inn. The original structure was destroyed twice, by fire and by hurricane, and rebuilt on the same spot, just a few hundred yards from the Port Aransas harbor. It’s still a determinedly out-of-time place, a long two-story wooden building with shady porches running the length of each floor, its rooms furnished with antiques and unburdened by phones or televisions. Covering a good portion of the wall space in the lobby is a parchmentlike tapestry of fish scales, all of them the oversized scales of tarpon, signed and dated by proud anglers. There are more than seven thousand. Near the reception desk, not pinned up on the wall like the others but carefully preserved in a frame, is a fan-shaped translucent scale with the signature “Franklin D. Roosevelt.”

Roosevelt was one of the many fishermen who came to the Texas Gulf to try his luck off the Port Aransas jetties. He arrived on the presidential yacht, the Potomac, in the spring of 1937. When it came time to seriously fish, he was transferred to a lowly Farley boat. One of his guides was Don Farley, whose brothers ran the local Farley Boat Works and who is still regarded as the finest of all the Port Aransas tarpon guides. (According to one admiring writer of the time, Farley could “handle a light Hoag salt rod as skillfully as the average American statesman can handle his conscience.”) Roosevelt’s tarpon expedition was documented by Life magazine and by newsreel photographers, whose footage of the president fighting and boating a five-foot tarpon can still be viewed today.

In addition to signing a fish scale, Roosevelt signed 32 acts of Congress during his sojourn on the Texas Gulf. While aboard the Potomac, he received word of the Hindenburg disaster. Anchored just offshore from the Tarpon Capital of the World, the president wired his condolences to Adolf Hitler.

Aside from such historical tangents, however, Roosevelt’s experience in Port Aransas conformed to that of other anglers. He had good luck fishing because the fishing was good. “Where They Bite Every Day” was the town’s defensible slogan, and the surf beyond the jetties was stippled with the fins of tarpon exuberantly breaking the surface. That was the way it used to be. That was the way it was almost all the time—until the tarpon went away.

I grew up in Corpus Christi, across the bay from Port Aransas. As a boy, those moldering fish scales in the lobby of the Tarpon Inn were the closest encounter I had with the storied fish itself. By that time, the mid-sixties, the reign of the silver kings was over. There were mounted tarpon everywhere, in bait stands and fried-shrimp joints, their scales slowly turning a musty gold as the oil in their dead skin leached out. Businesses named themselves after tarpon, and illustrations and cutouts of Port Aransas’s totemic fish adorned billboards. But the tarpon themselves were mysteriously all but absent, seldom seen anymore rolling in the surf, no longer traveling in schools so great that, as the old-timers remembered, you could almost walk across the water on their backs.

In fact, I never saw a live tarpon until I was in my forties. Scuba diving through a series of coral tunnels on the south end of Grand Cayman Island, I caught a bright flash of silver out of the corner of my eye. When I turned my head, I saw a school of prehistoric-looking fish swimming along beside me, their tightly spaced bodies reflecting the sunlight like a giant moving mirror. There was no mistaking the oversized scales, the bony, upward-configured mouth that opened almost flush with the top of the skull. Most of them seemed to be four or five feet long. They were used to divers, and my presence didn’t spook them. As I swam, it was strange to be so placidly accompanied by creatures I had begun to think were half-mythical.

Tarpon look ancient, and they are. They’ve been around in their present form for 18 million years. Like other primitive species of fish, they are to some degree air-breathers, taking in oxygen through their open mouths and a dorsal network of capillaries whenever they break the surface. This ability to breathe earthly air makes them more tolerant of oxygen-poor waters, an advantage for pursuing prey and evading predators. They are fast, taut, propulsive fish, capable of leaping high out of the water to outmaneuver sharks, powerful enough to remain stationary in the equivalent of class V rapids. The thick scales that cover their bodies like chain mail are another survival advantage. Tarpon can live eighty years. Some of the fish I encountered that day in Grand Cayman might have been alive when Archduke Ferdinand was assassinated.

Tarpon are a wide-ranging species on both sides of the Atlantic, and they range wide in the human imagination as well. At first I didn’t believe it when I was told that Michelangelo had painted a tarpon on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. But when I went online and took a virtual tour of the frescoes, my amateur’s knowledge of tarpon morphology made it hard to conclude that the “great fish” depicted with Jonah is anything other than a Megalops atlanticus.

It’s known from long observation by fishermen, and by more recent satellite tagging, that tarpon are warm-water, migratory fish. A tarpon begins life in deep offshore waters as something called a leptocephalus, an eerily transparent larval stage. As they develop, the tiny leptocephali ripple their way out of the broad ocean and into the shelter of estuarine waters, where in stagnant lagoons and mangrove swamps they morph into their final, recognizable form. As adults, tarpon tend to inhabit nearshore waters, bays, and rivers. They spend the winters in southern latitudes, then move north along the coastlines as the waters warm.

Tarpon are astute at making their migratory route a moving banquet, appearing at just the right time in the right places, where various food sources—ribbonfish, blue crabs, polychaete worms—gather in abundance to spawn. In the Gulf of Mexico, the fish seem to follow two migratory tracks, one leading up from Mexico and along the Texas coast, another paralleling the Florida shoreline. The two migrations meet at the mouth of the Mississippi. In late summer or fall, the tarpon head southward again. They follow the same steady band of warm water—the 26-degree-Celsius isotherm—that generates hurricanes.

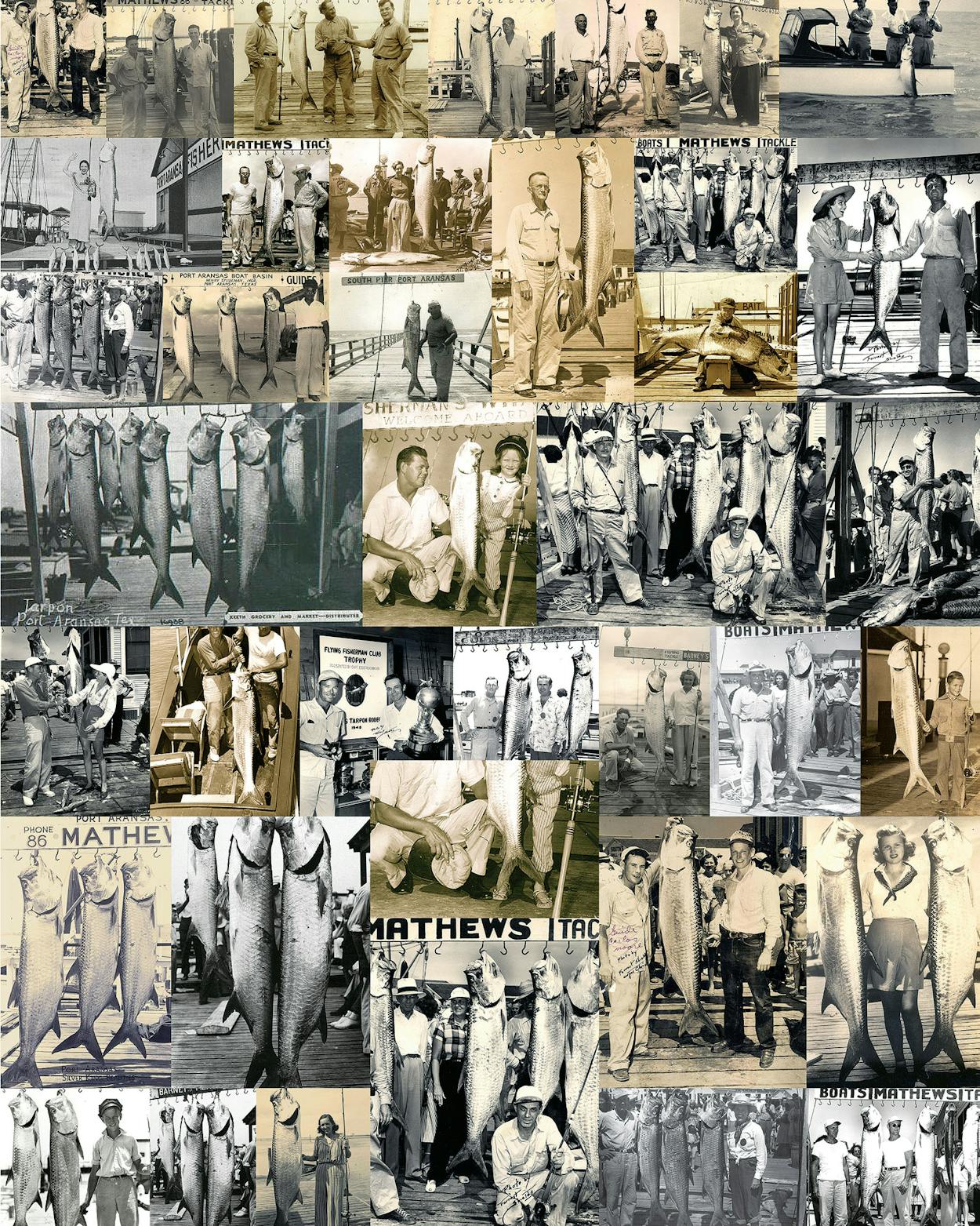

Port Aransas was once a major stopover on this itinerary. “The tarpon made our town,” Rick Pratt, the director of the Port Aransas Museum, emphatically told me. One of the highlights of the museum is an imposing stern section of a Farley boat. On the walls are historic photos of smiling men and women posing with huge tarpon that they wrestled from the sea. These are images from a different time, a distant ethos. Some of the photos show dolphins harpooned for sport and laid out on the docks as if they were vanquished sea monsters. In those days, before catch-and-release was a guiding precept, tarpon were caught to be displayed: photographed hanging on the dock or mounted by the venerable Port Aransas taxidermy firm of Roberts and Brundrett—in either case, dead.

It’s a safe bet that few of those deceased fish ended up on the dinner table. In Mexico, tarpon meat is sold in fish markets, and the creature’s enormous roe sacs—twenty to forty million eggs per female—are eaten, in the words of one visibly impressed witness, “like corn on the cob.” But north of the Rio Grande there are few tarpon gourmands.

“You might as well be chewin’ on a dadgum mop,” said Johnie Martin Mathews. Like Milina, Mathews is one of the old-time Port Aransas guides. He has a sparse Fu Manchu mustache, and the day I met him, he was wearing frayed red suspenders, a flannel shirt, and a baseball cap that read “Old Fart.” He told me about an incident that took place in 1949, when he was a seventeen-year-old guide. He had been standing at the side-mounted helm of his Farley boat one day with a client, a woman from San Antonio who had never been fishing. “We were down in the surf, and the tarpon were thicker than flies,” he remembered. “They was jumpin’ everywhere.” His client had just asked if tarpon had ever been known to jump into a boat when one of them did exactly that, rocketing out of the water, hitting Mathews on the shoulder and landing in the bow, thrashing and bleeding and tearing up the boat until it died. Mathews didn’t know it at the time, but the era when the surf off Port Aransas was so full of tarpon that one might just leap into a boat was already coming to an end.

“I got in right at the last of the big-time fishing,” he said. “From 1955 on, there was a decline in the tarpon. And I mean it wasn’t a gradual decline, it was just kaboom!”

Another Port Aransas guide from that era, Lloyd Dreyer, recalled the fall-off being less precipitous but still as dramatic. “It was a period of a few years,” he told me. “It didn’t happen overnight, ’cause we had so many fish—my goodness! But they just played out. God, I hated that.”

In any case, at some point by the mid-sixties or so, they were gone—or at least gone enough for tarpon fishing to no longer make sense as an industry. Port Aransas’s emblematic fish became a wistful civic memory. Anglers turned their attention from trophy fish to food fish—to the redfish and trout and flounder that were still relatively abundant in the bays and lagoons. The fishermen who pined for a muscle-depleting fight with a leviathan pushed far offshore in search of sailfish and marlin, past the surf line where the tarpon used to be.

What happened to them? Almost everyone I posed the question to referred me to the great Texas drought of the fifties. The drought lasted ten years and forever altered the state’s economy and identity, bankrupting farmers and ranchers and sending their children fleeing to the cities, hastening the state’s transition from a rural to an urban place. To protect itself against a future drought of that magnitude, Texas went on a dam-building spree, trapping in reservoirs much of the freshwater that used to flow into the bays. The resulting increase in salinity affected the populations of crab and shrimp and other food sources that had made the inland waters such a hospitable place for tarpon to linger. The dredging of ship channels, the surge in oil and gas production along the coast, and the pollutant-rich runoff from cascading development further damaged the quality of the water.

Increasing boat traffic along the Texas coast also likely grated on tarpon nerves. Tarpon are sensitive, wary fish; when Mathews was a guide, he liked the water to be a little greenish, a little muddy, or else the hyper-alert tarpon could see him way before he saw them. Scott Alford, a Houston lawyer who runs a website for anglers called Project Tarpon, believes that the fish are especially susceptible to boat noise because the air-filled swim bladders through which they control their buoyancy are located next to their ear bones, amplifying the sound of a boat motor churning through the water.

Overfishing played a role as well. Mature tarpon were routinely killed in tournaments and rodeos all up and down the western Gulf, and sometimes they were dynamited or netted in rivers and inlets and their carcasses used for fertilizer. They were caught on commercial long-lines and by innumerable subsistence fishermen. When I spoke with Jerald S. Ault, a marine biologist at the University of Miami and the director of the Tarpon and Bonefish Research Center, he described tarpon as “running through a gauntlet of fisheries” on their migration up from Central America.

With tarpon migrations along the western Gulf becoming an increasingly dangerous voyage, and with environmental degradation along the Texas coast drastically reducing food resources, the fish’s population dropped off so abruptly, so emphatically, it seemed that they would never be seen again off the Port Aransas jetties or in the surf of Mustang and San Jose islands.

The silver kings were gone, but not flat-out gone. The fish still swam north in the late spring, still swam back south in the fall, just in far fewer numbers. People still caught tarpon, sometimes by happenstance, sometimes by obsessive persistence, but for most Texas fishermen, tarpon were the relic species of a time that would never come again—something only to dream about.

One of the dreamers was Mike Williams, a Galveston fishing guide who remembered as a boy in the fifties the enthralling sight of thousands of tarpon off Galveston’s Flagship Pier. When he started guiding, in the seventies, there were few tarpon in evidence, but they still preyed on his imagination when he took his clients out into the deep Gulf waters in search of kingfish.

“Anytime I heard of anybody catching one, I’d call him up,” he told me. “I didn’t want to know exactly where he had caught it; I was more interested in the depth of the water he’d caught it in.” After a few years of talking to people who had caught tarpon and drawing an X on a chart to mark the depth in which each fish was taken, Williams was left with a puzzling document that made no sense until he started to connect the X’s with a line. The line, he discovered, made a “freeway in the Gulf.” Maybe the big tarpon had largely disappeared from the bays and the surf, but Williams was convinced that they were still out there in fishable numbers. They were swimming, he believed, in an offshore corridor twenty to forty feet deep, which he christened Tarpon Alley. He felt so sure of this that he started a tarpon guide service, in 1983.

“Everybody thought I was crazy,” he said. “I had a booth at the Albert Thomas Convention Center, in downtown Houston, and some of the best guides in the state came up to me and didn’t believe I had the gall to charter for tarpon. In any magazine you picked up, they pretty much all said the same thing: the tarpon were gone.”

But the tarpon, it turned out, were just keeping their distance, no longer attracted to the once-bountiful estuaries and concentrating instead on feeding in the open waters. Now, thirty years after Williams and other guides began targeting the fish, it’s hard to argue that they haven’t made a modest comeback in the Texas Gulf. Whether this is because fishermen are getting better at locating them or the tarpon population is actually recovering is hard to say. But perhaps it’s an encouraging sign that a new state tarpon record was set as recently as 2006, when Jeremy Ebert, who was fishing for redfish off the Galveston Fishing Pier, ended up hooking a 210-pound, 11-ounce tarpon that took six men to haul out of the water, an ordeal that left the fish dead of exhaustion.

If there’s a center to this somewhat revived tarpon fishery, it’s no longer Port Aransas but the upper coast, where Williams and a handful of other guides target the silver kings for their clients. Williams runs his company, the Tarpon Express, out of Galveston, generally stalking the fish from Rollover Pass on the Bolivar Peninsula to San Luis Pass at the southwestern tip of Galveston Island.

Jim Farley fishes the Galveston waters as well. He’s the grandson of the storied tarpon guide Don Farley. Jim lives in League City, where he’s a chemist for ExxonMobil, but he grew up in Port Aransas fishing for pompano and sea trout with his grandfather. They’d scout out the places where in Don’s guiding years there had always been tarpon, but Jim had been born too late—he never saw one.

He sees them now, however. In the early nineties, the fish started showing up in significant numbers off Galveston, and these days when Jim goes out in his 23-foot Contender (he doesn’t own a Farley boat), he sees schools that number in the hundreds.

“During the right time of year, during good weather, you’re pretty much guaranteed you’re going to see some,” he said. “On my final trip last year, I jumped ten fish and landed three big ones, a couple of them in the 150-pound class. Some days are spectacular. Anytime you go out and land a fish off the Texas coast these days, it’s a great day.”

But a great day in our time is not the same as a great day before the dams were built and the waters were assaulted with noise and toxic runoff and the buried pollutants stirred up by the ongoing dredging of canals and ship channels.

“Say you looked out on the plains in about 1800, and you saw millions and millions of buffalo,” Williams told me. “What I’m telling you is there’s thousands and thousands of buffalo. You see what I mean? There’s still a lot of fish there. But the tarpon coming back—that’s a fairy tale. In the real world, and I hate to tell you this, there ain’t nothing coming back.”

I wanted to see a tarpon. It was January, though, and the water was too cold for the fish to be migrating through the Texas Gulf. If I waited until summer, I could hire a guide and venture out into Tarpon Alley to try to catch one. But I didn’t want to catch a tarpon. I understood the primal allure of wrestling one of these great fighting fish out of the ocean. I understood it, but I didn’t feel it, at least not powerfully enough to justify disturbing a tarpon in the first place.

“They’re mysterious fish,” declared David Abrego, the facility director at Sea Center Texas, a Texas Parks and Wildlife Department fish hatchery and marine education site in Lake Jackson. I was standing with Abrego and Shane Bonnot, the hatchery manager, in front of a 55,000-gallon aquarium. At the bottom of the tank, a big green moray eel swayed like a cobra from a length of pipe. Above it, mixed in with a dozen other deepwater Gulf species, swam two four-foot-long tarpon.

The tarpon shone as brilliantly as they had that day I’d seen them in Grand Cayman. Their scales were as big as the conchos on a Mexican saddle, overlaid so precisely that they looked like the work of an artisan. When the fish worked their mouths, hinging them open and closed, I had the impression of snugly designed machinery. Their oversized eyes were black dots in an orbit of silver.

The tarpon had been caught when they were very small in a drainage ditch in Ingleside, on Corpus Christi Bay. One was slightly bigger than the other and was twelve years old. If it lived to its allotted eighty years, I calculated, it would not die until 2081. The more I watched the two fish, though, the less remarkable this thought seemed. They were so steely and expressionless, and so measured in their movements, they seemed likely to outlast anything else alive.

“They’re beautiful and graceful,” Bonnot observed, “but they’re a little more introverted than the other fish. They don’t interact.”

The tarpon don’t have personalities, or at least not personalities that are discernible to human observers. This isn’t true of some of the other fish in Sea Center Texas. The tripletail was friendly, as was the big grouper—named Cooper—who made his eternal rounds through the tank a few feet lower than the two tarpon. There had been another fish, a big Queensland grouper named Gordon, who had lived in the tank for twelve years and for whom the staff had held an annual birthday party at which as many as seven hundred schoolkids showed up. Gordon died—or, as Abrego more solemnly phrased it, “passed”—in 2008.

The tarpon don’t have names. They don’t come up to the glass to study visitors like Gordon used to do. They just implacably swim, on and on, their eyes fixed upward toward the top of the tank, where three times a week a human hand will appear to feed them mackerel and squid.

The tarpon at the Texas State Aquarium, in Corpus Christi, don’t have names either. I went to visit them on Martin Luther King Day, when the aquarium was jammed with families taking advantage of discounted admission prices. At a facility featuring dolphins and puppylike river otters and ethereal jellyfish, a captive tarpon is understandably not the most compelling creature on exhibit. Nevertheless, it was for me. There were three of them in a big tank labeled “Islands of Steel,” in which they slowly circled with other fish around a habitat meant to represent the underwater pilings of an offshore drilling rig.

“They just eat and eat and eat,” said Jesse Gilbert, the aquarium’s director of animal husbandry. “They are ferocious eaters. They will attempt to swallow anything at the surface of the water, whether it’s a food fish or sunglasses. Other than that they’re pretty easy. Nobody messes with the tarpon, and they really don’t mess with anybody else.”

The lighting was lower in the aquarium than it had been at Sea Center Texas, and the water was darker, making the tarpon shine even more brightly, their silvery scales and tapering, narrow-beamed bodies flashing like knife blades. But in truth they didn’t stand out all that much, not in a tank crowded with amberjacks and nurse sharks and other species of sizable deepwater fish, all of them so compellingly unrevealing, so blank and unresponsive to our human itch to find evidence of a recognizable inner life. I’m sure I was the only person at the Texas State Aquarium that day, or that month, or that year, who had come specifically to see the tarpon. For most people, they would probably register as just another anonymous fish. It was only on the end of a hook that a tarpon was transformed into something wondrous.

Because of this simple biological quirk—the fact that a tarpon, in fright and in pain, will leap out of the water rather than drive down toward the bottom—Port Aransas had, for a time, a place on the world stage. That old Port Aransas, the one where presidents came in search of the silver kings, can still be glimpsed among the condos and hotels that now rise up in the center of town and spread southward through the dunes of Mustang Island. The cavernous beachwear boutiques and strip malls and restaurants filled at breakfast with snowbirds in polo shirts that read “ROMEO (Retired Old Men Eating Out)” have not totally obscured the working fishing village that once was here. The Tarpon Inn still stands near the harbor, and so does the Farley Boat Works, which has been reborn as an educational center where people with a deep enough interest in the old ways of the tarpon capital can learn how to build their own skiffs.

And of course the jetties that Milina’s father helped build, and through which the tarpon once cruised as they moved from the Gulf to the bays and back again, are still there as well. The day after I visited the Texas State Aquarium, I took a walk on the south jetty all the way to the end. It was a brilliant winter day with not much wind and not much boat traffic, the water a little greenish, just like Mathews used to like it.

There were fishermen all along the length of the jetty sitting in folding chairs. There were ruddy turnstones flitting across the granite boulders and brown pelicans standing about on their webbed feet. The Lydia Ann Lighthouse, built in 1857 and sabotaged by Confederate troops in the Civil War, rose out of the flats across the channel.

I wasn’t looking for anything in particular as I walked past the point where a rough sidewalk ended, making it necessary to proceed more cautiously along the jumbled boulders. But I saw something up ahead in the surf that sparked my attention: it was a fish, seeming to idle on the surface. Not a big fish, but it was at least two and a half feet long, and the way it wagged its body sluggishly back and forth, its dorsal and caudal fins showing above the surface, made me think—made it impossible for me not to think—that it might be a tarpon rolling along in the surf.

I hurried to get a better look, slipped on the algae-covered rock, and scrambled up again. When I was closer, I saw that the fish was drifting helplessly, washing up against the jetty, and that one of the fishermen I had seen was leaning down to grab it by the tail.

It wasn’t a tarpon. It was just a bull redfish, over the allowable size limit. The fisherman had hauled it in, released it, then left it alone to recover strength after its struggle. Now he was pumping it by its tail, running seawater through its gills, trying to revive it.

I watched as the fish swam groggily away against the surge. I scraped the algae off my pants with my car keys. For a moment, I really had thought it was a tarpon, and now I felt foolish. I should have known better. I should have remembered it was the wrong season, the wrong era, the wrong world.

- More About:

- Fishing