This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

The party has been going on for two hours, and no one will touch the cake. It sits there, rich and beautiful, the words “North Bodies” written in glistening print on the white icing. A chunky middle-aged couple, forks in hand, hover nearby, but they glance at one another uneasily. Should they be the first? Obviously, these are not North people. Two North women are over by the wall, in high heels, their dresses just short enough for everyone to see not only the perfect muscles in their calves but also the lean shapes of their thighs. When they walk, the fabric of their dresses slides across their hips.

They are not walking toward the cake. No one is. The man and woman with the forks have probably never been to a party like this in their lives. Think about it: a bunch of food is laid out, and the partygoers all act as if they don’t see it. They prefer instead to sip bubbly water and say things like “I’ve got to do more arms,” “I’m on broccoli and oat bran,” or “First, I do three sets of incline presses, and then I go to the crossover pulls.”

It’s not that these partygoers look like granola-heads, that intense subspecies of humanity that hangs out in health-food stores. These people have a wealthy glow about them, even in their casual clothes—their Polos and Donna Karans. They are the type one would find at the Cattle Barons’ Ball, Dallas’ swanky society soirée. In fact, there is last year’s chairman of Cattle Barons’, Teddie Garrigan, confiding to a friend that she works out with an expert in the martial arts. Here comes Henry S. Miller III, maybe not the richest but certainly the fittest real estate man in town. And over there is the suntanned Jan Rogers, a part-owner of the Dallas professional soccer team who has just jetted in from Aspen, where she has opened her own restaurant. “I also have a trainer when I’m in Aspen,” she is saying. “You know, Jean Robert, the Frenchman.”

What is the deal? Why is it when someone gives you a big hug at this party, his or her hand slides down to your waist just to see how tight you are? Why is one blond socialite saying to another, “Boob jobs are out, but muscular chests are in”?

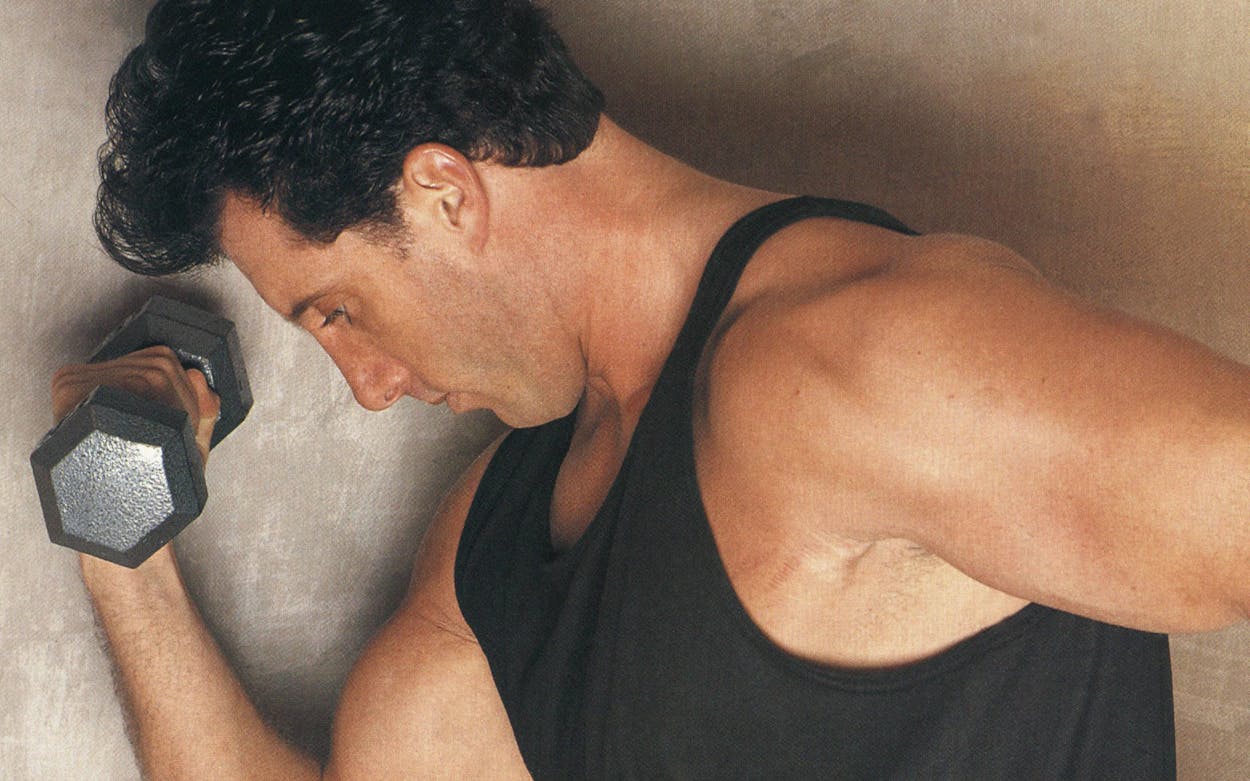

But of course! They are all trying to impress the host of the party, the perfectly put-together man, the fitness kingpin of Dallas society—Larry North. That’s him in the blue jeans that are like a second skin, the one who’s six feet two inches tall, weighs 212 pounds, and has only 9 percent body fat. Check this guy out. He’s thirty years old and single. His biceps are like grapefruit with veins, his shoulders slope like great hillsides, his thighs are the size of cruise missiles. And on top of all that, with his dark eyes and dark brushed-back hair, he looks like a handsome cross between Sylvester Stallone and John Matuszak, the football star turned macho actor. An expert schmoozer, astonishingly charming for someone you might expect to be just another muscle-head, North works the crowd, telling his clients how good they look. “Listen to me,” he says with confidence to one enraptured lady wearing that kind of billowy blouse meant to hide excess tonnage, “you’re not going to believe what you’ll look like after a month.”

The husbands of North’s female clients stand a few steps away, their stomachs sucked in, their faces a bit sheepish, knowing that they’re spending way too much time behind their desks while this super-stud personal trainer is turning their wives into . . . babes! But almost everyone else—young people trying to reach peak form, middle-aged people trying to regain their form, a couple of grandmothers who look as if they have never been out of shape a day in their lives—gathers about their hero the way Dallasites once gathered about Stanley Marcus. Now it’s Larry North who creates their images, by shaping their bodies and telling them exactly what they should eat and when they should work out.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” North says to the crowd of more than one hundred, ”I just wanted to say thanks for making this year such a success. I know there are a lot of great things about to happen. But I couldn’t have done any of it without you. So this party is for you.”

The North maniacs applaud madly. But even when Larry North himself breaks one of his ironclad rules and takes a bite of cake, no one else dares to follow him. “You know my rule against sugar, but it’s okay to eat it this time,” Larry announces. “It’s a party.” Still the crowd won’t touch it. No, it’s more important that they make their leader proud of them. They back away. In this new Dallas social stratum, where status is determined by the hardness of one’s body, people want to have their cake but not eat it too.

It hardly seems possible that a Jewish bodybuilder from Long Island, New York, who used to lift weights during the day and work as a doorman at rock and roll clubs at night, would end up with the most exclusive gym in town. Or that, without any broadcasting experience, he would get his own weekend radio talk show. Or that he would acquire a literary agent even though he has never written anything longer than a term paper. Or that eight Dallas restaurants would name a special healthy meal for him even though he is an average to lousy cook.

Frankly, big weight-lifting brutes are a dime a dozen in this city. Personal trainers are everywhere. “Having a personal fitness trainer has become to society in the nineties what cocaine was to the eighties,” says Kirby Warnock, the editor of SportsPulse, a monthly magazine read by at least 30,000 in Dallas. “It’s a way of saying, ‘I have money.’ ”

It’s not as if Larry North was the first to come up with the idea of opening a gym to become rich and famous. Trying to take advantage of overweight people’s guilt is an American tradition. Considering the number of health clubs in Dallas alone, a man could bench-press himself across the city. Says Warnock: “I get calls and letters every day from people who tell me they are the leading trainers or aerobics instructors in Dallas, and why the hell haven’t I done an article on them? My God, we’re overrun with them.”

Yet Larry North is emerging from the pack to become the biggest fitness celebrity in the city. A local casting agent is looking for movie roles for him. His press agent plans to call the Oprah Winfrey show to propose that North work for free with the television hostess for six weeks to get her in shape. His literary agent is helping him with a motivational book. Unabashedly, he talks about starting his own apparel line, expanding a highly nutritional series of meals named after himself into major restaurant chains like Chili’s Bar and Grill, syndicating his radio show nationwide, and beginning a television talk show about fitness. Meanwhile, as he grooms himself for stardom, he spends about fourteen hours a day at Northbodies, his gym, training himself or someone else.

It’s a pretty good bet that the most self-absorbed creatures on earth are brawny men who like to stare at themselves in health club mirrors. But North learned early on about the assets of an attractive personality. In 1980, while hanging out at a rugged Dallas bodybuilders’ gym, North approached a woman looking for a personal trainer. Jan Miller, a workout fanatic and a Dallas literary agent, had made her mark in publishing by promoting an Arnold Schwarzenegger book on health, and she saw something similar in this young hunk with rippling pecs. While resting between sets, she listened to him describe his grand plan to make a career out of fitness. “I have to say that every time I worked out with Larry, I kept seeing the next Arnold. He was street smart, he wasn’t arrogant, he had a gift for liking people. I said, ‘Larry, you could write a book,’ ” Miller recalls.

North believed her. He felt that his family background was interesting enough: His father had been featured on 60 Minutes as a compulsive gambler who had been in and out of prison for swindling banks to pay off gambling debts. In 1978, to get away from his father, sixteen-year-old Larry, his mother, and his younger twin brothers secretly moved from Long Island to Texas, which then had no legalized gambling. The family was poor; Larry worked several after-school jobs to help his mother out. But right after moving to Dallas, while sitting on the toilet, he realized he had yet to become a man, that someday he might have to stand up to his father. “I looked down at myself,” he recalls, his face very serious, “and saw that my stomach pooched out and my chest caved in. It was sickening. Two days later, I was in a gym.”

For a long time, it seemed that North would go nowhere. Throughout most of the eighties in Dallas, perky aerobics queens were the city’s exercise celebrities. Bodybuilders like North (he placed fifth in an Amateur Athletic Union Mr. Texas competition in 1985) were still considered Neanderthals. He did become one of Dallas’ best-known nightclub doormen—women loved to giggle out a “Hi, Larry” as they swept into the nightclub of the moment, and wealthy men would slip him $100 tips to get them a good table—but he knew he was just being used. “You wouldn’t believe the stereotypes I’ve had to live with: the big-lug bouncer, the dumb jock,” he says matter-of-factly, a slight trace of a New York accent still in his voice. “I’d tell people about my plans to open a gym, and they’d say, ‘Yeah, good to see you, Larry.’ ”

Oh, well, as they say in the muscle business, no pain, no gain. North continued to read all the muscle magazines, consulted with nutritionists, and joined a dozen health clubs around the city so people could see his face—well, make that his body. People would take one look at this pumped-up dark-haired stallion and say, “Hey, I’ve got to look like that.” He was a master at PR. In the late eighties, North would arrive every day for lunch at the 8.0, one of Dallas’ most popular see-and-be-seen spots, and order the same meal—a grilled chicken breast, brown rice, and a steamed vegetable. Soon the restaurant began calling the dish the North Plate. His arrival at the 8.0 became a ritual: He would stroll in wearing shorts and a tight T-shirt, the veins in his arms sticking out like number two pencils, and everyone would turn and stare. Without his saying a word, the North Plate would be set before him. He has to be famous, the customers would murmur. Indeed, perception became reality. It wasn’t long before he was getting stories written about him in the local newspapers.

North’s shtick—aerobic exercise to burn body fat, weight training to increase lean muscle tissue, and several small meals a day consisting of proteins like chicken and starchy carbohydrates like a plain baked potato—was not new. When training someone, North did not use an overly spirited Jack LaLanne a-one-and-a-two style. He simply relied on a boy-next-door enthusiasm. “Come on, lift it one more time,” he would plead, looking sincerely into his client’s eyes. It was hard not to like him when he told you how overweight you were.

Most important, North learned to tailor his message to well-to-do Dallas, a group that quickly turns on to power and powerful people. Jan Miller introduced him to those who had time to discuss their lives over long lunches. North would give them his most impassioned speech about the advantages of lifting weights. It struck a chord among those who realized that muscles could be a sign of status, proof that one has the leisure time to train.

As a personal trainer, North would travel from home to home. From the noble mansions of Highland Park and North Dallas, his voice would shoot forth like a bugle call: “One more! One more! Squeeze the muscle!” He demanded that his clients lift weights for an hour three days a week and do thirty minutes of aerobic exercise five days a week. His clients were mesmerized—they would stare at him the way teenagers stare at a rock star. Music agent, theater operator, and man-about-town Angus Wynne was so inspired that he set up a gym in an upstairs bedroom for his workouts with North. Others brought North with them to their own health clubs. He charged $60 an hour for a training session, the highest price in town.

But North was still not satisfied. In April 1989 he showed up unannounced at KLIF-AM, a talk radio station, and enthusiastically told program director Dan Bennett that what the city really needed was a talk show about fitness. Within a minute of the conversation, Bennett knew he was going to try North out. He put him on early one Sunday morning, when few people listen to the radio, and North took to the microphone like a pro, launching into every conceivable subject, from workout equipment to the horrors of crash diets. “The phone lines lit up,” says Bennett. “I realized that people secretly wanted to get in shape but were too embarrassed to ask about it except from the privacy of their own home.” He moved North’s show to a midday slot on Saturdays and Sundays. Now about 10,000 listeners tune in to the Weekend Workout to hear such Northisms as “It’s not who trains the hardest, but who trains the smartest” and “If you don’t steam it, grill it, broil it, bake it, or boil it, your food’s got too much fat in it.”

When North was ready to open his own gym last April, he already had a string of prominent Dallas names waiting to get in. There were members of the Hunt, Perot, Dedman, and Horchow families. There were charity ball women beaten down from years of climbing the social ladder. There were real estate developers and Highland Park moms. When they arrived to check out North’s studio at the posh Highland Park Village, the home of such breathtakingly expensive boutiques as Hermès and Chanel, they discovered, to their bewilderment, a stripped-down workingman’s barbell gym. There were a few exercise bikes and treadmills and Stairmasters, but everything else was weights—leg-lift machines and dumbbell curl benches and huge iron plates connected to bars. Lots of clanky stuff that looked as if it could kill you. The gym was small—about the size of some of his clients’ three-car garages—and it didn’t even have a locker room where the beautiful people could change clothes or do their hair. North, however, would slap them on the back and say, “Just wear anything. You don’t have to put on makeup.” Suddenly it became trendy to dress in baggy gym clothes and act like a gym rat. Junior League matrons would lift and strain, letting out gasping sounds that in any other circumstance would arouse compassion.

North opened his gym on a shoestring budget (he borrowed $15,000 to open it and prayed that membership fees would pay for his first months’ rent), but he refuses to expand his membership list just to make more money. “I hate big hard-sell health clubs where everyone is stepping over one another to get to a machine,” he says. Today Northbodies has 140 members, 60 of whom are personally trained by North or one of his seven assistant trainers (who charge only $40 an hour). Among the trainers are his twin brothers, Adam and Alan, who are fiercely loyal to Larry. All three of them communicate with their father, who drives a cab in Las Vegas. When his father unexpectedly called Larry’s radio show in February to wish Larry a happy thirtieth birthday, Larry began to weep.

That side of North might be the very key to his success. People are always surprised that a behemothlike man can be so sensitive. But watching North work as a trainer, it becomes obvious that his clients treat him the way they would a good hairdresser. As they move from one machine to another, they end up telling him everything about their lives. Obviously, North knows what he is doing as an instructor, but so do dozens of other trainers in this town. “Let’s face it,” says Kirby Warnock, “personal trainers don’t have some special secret to getting you fit. You pay them to get your butt out of bed and work out. You pay them for their motivation. And there are few people who do that like North.”

North arrives at his gym at five in the morning to begin his own workout. He moves from machine to machine, taking no breaks, his eyes squinched in concentration. By six o’clock his first client arrives for training. “Let’s do it,” rejoices North as he heads to the weights. His voice is a constant patter of encouragement. “Nice, nice!” he cries. “Lift it slow!”

Just before seven, he sneaks into the back room for the first of five meals—a glob of oatmeal and egg whites in a bowl that looks like a German shepherd dog-food dish—and then he lunges back out into the weight room for his next appointment. By nine-thirty he is at Gilbert’s, a North Dallas restaurant, wolfing down a North Omelet, made mostly of egg whites. He rushes out to get a massage, rushes back to the gym for more appointments, then suddenly he’s off to the 8.0 for his obligatory North Plate. He’s so picky about eating only the right foods that he will send an entire dish back if there’s the slightest bit of butter in the sauce on the vegetables.

Clang! His fork slams to the table. “Gotta move,” he says. It’s back to the gym for the afternoon crowd and more training sessions. Then a quick consultation with a new member, who arrives in mink coat and wet fingernails. She’s still tentative about weight lifting. “It isn’t going to distort your body,” North says reassuringly. “I know. That’s what plastic surgery is for,” replies the woman, sticking her fingers straight out so her nails will dry. North grins. “Can you start tomorrow morning?” he asks. He runs out the door for another meal, this one a Chinese version of the North Plate, with steamed vegetables and chicken, at a restaurant called Tongs. Another clang of the fork. “We’re moving,” he says, and it’s off to Northbodies for yet another session. This is Northtime, everything moving faster than fast.

North’s assistant trainers, always nearby, will do just about anything to inspire their clients. Alan North reads a poem to an SMU coed who needs to study while she walks on the treadmill. “I wandered lonely as a cloud,” Alan solemnly recites, glancing around quickly to see if the other trainers are listening.

“What Larry has done,” says Dallas restaurateur Hank Coleman, “is create something that feels like an intimate bistro as opposed to a big steak house. It’s cozy. Everyone is comfortable and knows one another. And then there is always Larry, coming up to see if you’re okay.”

It’s hard to say, after all the Arnolds and Jane Fondas, if there is room for one more fitness celebrity. But that won’t stop North from trying. “Hey,” he says late one afternoon, “this is what’s important to me—revving people up, making them feel good about themselves again. That’s all I want to do. Listen, I get choked up when overweight people call me on the radio show, asking for some kind of help to lose weight. I care if one of my clients isn’t getting the right nutrition. I see that as my mission, to get the word out, to tell peop—”

Oops. He glances at his watch. It’s five-thirty, time for another appointment. A North woman has arrived in a little white T-shirt and gray leotard. She looks sensationally fit, but her face is anxious as she searches for her mentor. “Larry,” she says, “I don’t feel like I can move today.” He bounds across the gym like a young colt. “Come on,” he says, “you’ll do great. I know it.” She gives him an adoring look and heads toward a barbell.

“Beautiful,” says the fitness king, standing majestically over her in his palace of weights. “Now, just lift it slow. Just stay with me. That’s it. Nice.”

- More About:

- Health

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Dallas