Duncan Dining Hall looks like a place built for modern-day Olympians, which is exactly the impression it was designed to create. It is a cavernous, harshly lit space deep in the heart of Aggieland, at south end of the Quad, where Texas A&M’s corps of cadets dwells. The walls display romantic banners from corps outfits—everything from flying tigers to leering skulls, from knights in armor to menacing machine guns. Photographs commemorate moments of Aggie glory—a visit from Franklin Roosevelt, a must ceremony at Corregidor. Here the young warriors attack their manly meals of chicken-fried steak or hamburgers or sausage, along with mashed potatoes and gravy and all the pie a boy could eat, all served at blitzkrieg speed. Duncan, it is said by corps members with pride, is the fastest dining hall in the country. It can serve almost two thousand cadets in less than twelve minutes.

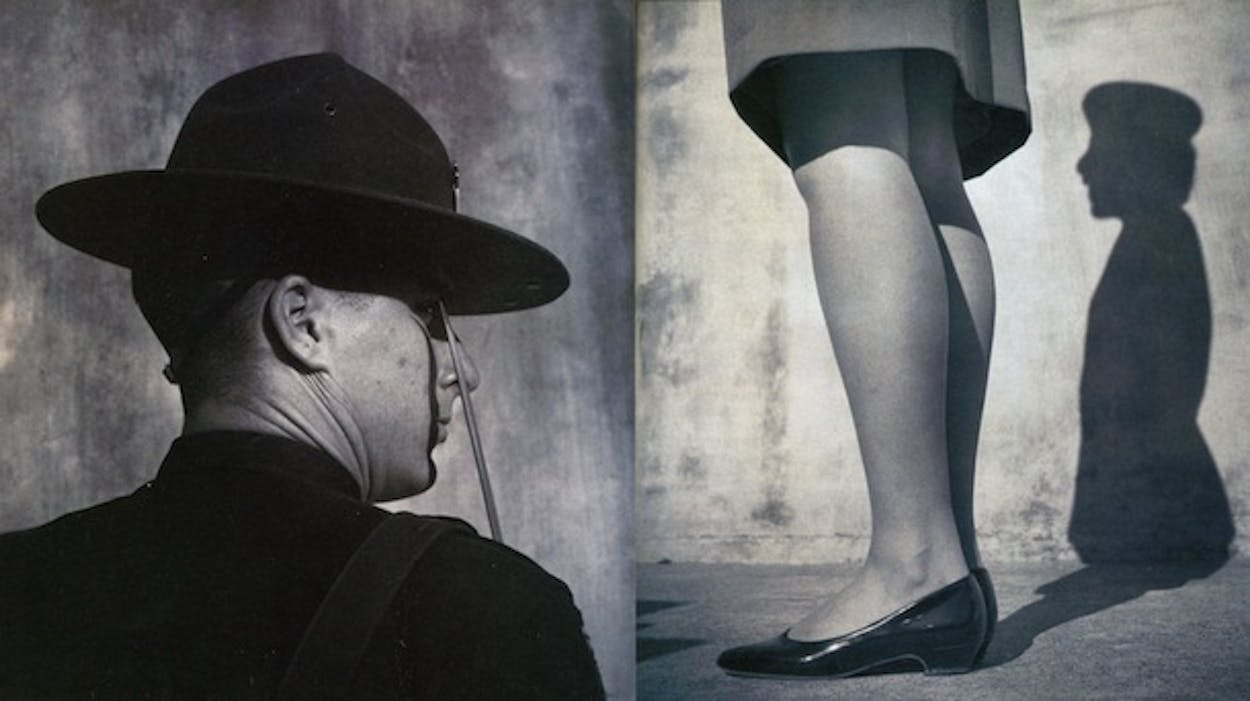

There is no escaping the extra-strength, unadulterated maleness of Duncan. Panning the room, you see a sea of young men in khaki uniforms, their hair shorn mercilessly close to their skulls. They wolf down food; they rise to bark orders or jump to respond to them; they march in formation to their seats. They bang on tables with their silverware; they spill food on purpose; they sing songs that only they can truly understand. Duncan fairly throbs with young men happy to be young men, secure in their belief that the camaraderie and trial by fire that has defined life in the corps for generations is the best preparation for manhood there is.

Only one small, almost invisible group looks less than delirious to be here. Look past the Lite Meal line, with its 1,800 calorie steamed-veggie section, just beyond the more than generous salad bar, with its mound of shredded carrots, and you will see some long, lonely faces. The khaki uniforms fit uneasily across these cadets’ chests, and they look sheepish, rather than sunny, when marching and chanting as they tote their dinner trays with their arms extending at precisely a ninety-degree angle from their bodies. They look as if they would rather not have to stand and recite another moment in A&M’s glorious campusology; they look, in fact, as if they would rather not be here at all. These cadets are the seventy or so women warriors at Texas A&M, and they are not alone in wishing that they could be elsewhere. Many of the 1,880 men here in Duncan regard the women not as colleagues, nor even as outsiders, but as outright enemies in a battle that is completely different from the male high jinks that are so much a part of Aggie tradition. In the corps, the war between the sexes is anything but metaphorical.

Seldom, however, has it been so public. As one male officer, sporting senior boots and enough ribbons and medals to impress a Third World potentate, explains, “It has been a long semester.” Since the beginning of the school year, several women corps members have charged their male counterparts with abuse ranging from assault to verbal harassment, all designed to drive women out of the corps of cadets. The accusations have resulted in what any Aggie would describe as “very bad bull”: The women were quoted in Newsweek and the New York Times, and they appeared, shrouded in shadow, on CNN, blackening the name of A&M in general and the corps in particular.

The current scandal began last September, when a female cadet reported that she had been surrounded by three corpsmen, one of whom threatened here with a knife, in an attempt to scare her out of an elite corps organization. Later she said she was the victim of what Aggies call a blanket party—she was kidnapped from campus, had a plastic bag put over her head, and was beaten by several corps members. Subsequently, several more women came forward with stories of their own, accusing male cadets of an ax handle beating, rape, and obscene insults. But the situation became clouded when the original accuser, whose name was never revealed, recanted her two stories. Opinion on campus is divided as to whether she did so voluntarily or under pressure. (She declined to be interviewed for this story.) The male cadets, meanwhile, have denied all accusations of physical abuse. As is so often the case in the war between the sexes—most recently in the Clarence Thomas hearings and the William Kennedy Smith rape trial—only the participants know the truth. But no one disputes that there is enormous hostility toward women cadets among male corps members.

The charges have sent the corpsmen—so secure until now about the world and their place in it—into a very un-Aggielike funk. “I’m so conscious of doing the right thing, I’m dysfunctional,” says one. Many cadets see themselves not as perpetrators of discrimination but as defenders of all that they—and their fathers and grandfathers before them—hold dear: the rough-and-tumble, resolutely male way of life that they believe should never have been open to females in the first place. Food fights, push-ups, crap outs—that’s life in the corps, and if women don’t like it, as the oft-applied Aggie aphorism goes, Highway 6 (College Station’s main business artery), runs both ways. “The corps is a hard place—it has its own culture, its own language, its own thoughts,” says a male corps member. “But the only time that is called discrimination is when it’s done to women.”

“I WANTED TO BELIEVE THIS WAS AN ACCIDENT,” Carolyn Muckley says grimly, referring to the day a male cadet kicked her in the back, near her kidneys. It happened in November 1991. Muckley, who is 22 and a fifth-year senior who graduated from the corps last spring, was sitting on the grass in a picnic area where she had just finished grading a group of cadets doing sit-ups for a fitness test. As befits a member of the Reserved Officers Training Corps, she was dressed in camouflage trousers, lightweight combat boots, and a black T-shirt that said “Army” in gold letters. The blow from behind was so severe that she pitched forward. “It hurt like hell,” she says. Muckley turned around in time to see a young man she recognized as a member of the corps. “Our eyes met, and then he walked away as if nothing had happened,” she says. She also noticed his T-shirt. It bore the logo of the Parsons Mounted Cavalry, the corps organization named in the knife threat incident. Muckley wasted no time—she went to the campus police, who charged the cadet with misdemeanor assault.

Carolyn Muckley is the unofficial leader of A&M’s feminist martyrs. It was Muckley who, after learning of the accusations of assault made by the woman who later recanted, came forward with charges of her own. To Muckley, most members of the corps are brutes, and to prove her point she presented an eleven-point letter to the school administration and the national press, documenting the abuses that she had experienced, witnessed, or heard about while she was in the corps. Male cadets, for instance, would not “whip out” to (greet) upperclasswomen. From there her charges escalated to accounts of beatings and rape. She also cited examples of verbal abuse—she had been called a “f—ing Wag.” (“Waggie,” which both male and female cadets say is derogatory, is a term applied to a female member of the corps.” When the first woman cadet retracted her accusations, Muckley marched into her place.

It is not an easy place to be. Muckley knows that female cadets reside at the bottom of the A&M social ladder. “People on campus don’t like the fact that there are women in the corps,” explains one student. “They see it as gross.” While women who date male corps members are admired, men who date Waggies are seen as losers. Corpsmen and corpswomen, of course, seldom date. In general, Aggies respect those who uphold Texas A&M’s traditions and abhor those who challenge them; female cadets who aren’t traditional women in any sense of the word, are flaunting the entire Aggie legacy by just being around.

Carolyn Muckley possesses precisely the qualities that many Aggies despise. She does not usually present herself as particularly feminine—she favors overalls, unruly curls, and no makeup—and she is, in their eyes, a whiner. Worse, she is a feminist: “I know my Title Nine rights,” she says, citing the sex discrimination statutes, and you are very sure that she does. Even more terrible, Carolyn Muckley does not see the value of Texas A&M’s treasured past. “Aggies are willing to forsake what is right in the eyes of the law for the sake of tradition,” she says. “It doesn’t matter what’s right or wrong. All that matters here is tradition.”

THE FISH TANK FILLED WITH POTATOES, Ping-Pong balls, and condoms sat largely ignored on a table at Texas A&M’s Memorial Student Center, right between the students selling sweatshirts for the polo team and the students offering applications for VISA cards. Its presence is an odd testament to momentous changes that are occurring at a university deeply wedded to the past. The fish tank is the brainchild of a group of A&M medical students who are sponsoring a safe sex contest in order to pay their way to Mexico to help indigent families.

“Guess the number of condoms for a dollar!” announces a bespectacled student named Mike, who with his girlfriend Rosa, is hawking the chances. Even though the prizes speak to student-style priorities—skydiving lessons, a two-month health club membership, dinner at two local restaurants—most Aggies skitter by. “It’s a good cause,” Mike insists to the passing crowd. “It’s AIDS! It’s in the news!”

A science professor makes his guess after taking some measurements with his hands; one good-humored man buys the chances for four starched and shorn corpsmen. But for most students, a sexually transmitted disease is not a draw. “Why should I?” challenges one potential buyer. “I don’t ever have sex.” Only a rare few respond like the Aggies of those famous jokes: “Are you going to put those in a little sack for me,” a pretty co-ed with a buoyant flip asks, eyeing the rubbers, “so I don’t have to walk around with them?”

This is Aggie sex today: confused, conflicted, and best avoided, a reflection of a school at social and sexual odds with itself. The real Aggie identity has been obscured by decades of Aggie jokes—the operative Aggie stereotype is not dumbness but an obsession with ritual and tradition. The school is, at its best, a place where the intense loyalty of students and alumni has aided the efforts of administrators and faculty to move A&M into the first rank of public universities. But the passion for the past has hindered the Aggie march toward the future.

No school is more ritualized than Texas A&M. Founded as the state’s first public college in 1871, it grew up isolated in the Brazos River bottomlands, a hundred miles removed from urban Texas in three directions—a college with a military mandate but a Texas soul. In Aggieland, legends and customs are attached to everything from the school ring to the bonfire before the annual football game against the University of Texas at Austin. It is the place where everyone was, for many years, required to say howdy and greet people by name; about which Clayton Williams cries each time he recalls his happy, happy years there. It is a fantasist’s paradise of honor codes and honorable deeds, where one of the enduring goals of the university is to pass the Aggie experience on unchanged from generation to generation. “It’s all about the old days,” explains one alumnus. “That’s what’s good about A&M.”

It was, above all, a man’s place—with a few exceptions, the daughters of professors were the only women who could attend before 1963—and even though the enrollment of 40,997 students, the nation’s seventh largest, is now 41 percent women, males still dominate in all respects. If Aggieland was once rural, physical, and anti-elitist—the most Texan of Texas schools—many of those traits live on in the social and sexual conservatism of the students. You don’t see dreadlocks or slashed jeans at A&M the way you might at t.u. (as Aggies refer to their Austin rival). Males are gentlemen when they have to be, but their hearts are in their hell-raising; the Aggie idea of a good time remains a ritual like the Flight of the Great Pumpkin, in which corps members try to pitch a pumpkin filled with feces into the band members’ dorm. Women here are expected to behave. They know better than to show up at the Texas Hall of Fame Club without a date, and while they may be as sexually active as women on other campuses, they talk about it less. A&M is a school for students who put their stock in old-fashioned values and keep it there.

The real guardians of this flame are the members of the corps of cadets. Though the school stopped requiring corps membership in 1963, and though the corps’s ranks have been thinning ever since, the organization still retains its emotional power over the school and, in return, its hold on the Texas identity. That is why the current Aggie scandal has resonated across the state with such force. To confront the sexual identity crisis at A&M is to come to terms with the last vestiges of a sexual identity and sexual fantasies that have shaped the Texas stereotype for generations. Like it or not, we have met the Aggies and they are still us.

JOHN SHERMAN, HANDSOME in the way that one would expect of a senior voted most popular, stands tall and impressive in his brass, braid, and burnished senior boots. As commandant of the corps of cadets, he moves through his world with impeccable posture, a good-natured formality, and a confident semi-swagger. His face is open and unclouded, at least until the subject of women in the corps comes up. Then he frowns and snaps his head sideways, as if he were warding off a slap to the cheek.

“I’d like some legal counsel,” he says, sitting under portraits of Aggie military heroes in the Guard Room at corps headquarters. “I want to know what exactly is discrimination.” Ever since Anita Hill accused Clarence Thomas of sexual harassment, he says, he doesn’t know what to say to women. Does a man get in trouble for treating a woman differently than he would treat a man? Or for treating her the same as he would treat a man—which is what the Aggies say they do? “Do you talk about ‘Did you get laid this weekend?’” he asks, his brow knit.

Sherman’s defense of the corps is the one made by most male cadets. He admits that discrimination exists, but he divides the women’s charges into those that “did happen, didn’t happen, or have been magnified.” The corps is getting better, he says, and the problems that do exist are limited to “a few bad apples.”

“With all these males,” he says, “if you try to cram it down their throats, you will alienate a lot of people who would come on board slowly.” Stepping out into the Quad, he points to a women’s dorm and talks about the dangers of mixing male cadets with women cadets too fast: “You don’t want the Russians in such close proximity to the Americans.”

Listening to John Sherman, you can see how he reached his present position. He embodies the Aggie ideal—his loyalty to his buddies is unyielding, his faith in the corps’s ability to police itself is unquestioning, he views women as both foreign and mysterious. He is proof that the Aggie experience can pass unchanged from generation to generation.

The inscription on the statue of Lawrence Sullivan Ross, the A&M president from 1891 to 1898, sets forth the virtues that Aggies are expected to emulate. The former Indian fighter, Confederate officer, and Texas governor is remembered as a “solider, statesman, knightly gentleman.” That standard was no easy trick for the school’s first students. “Many were more familiar with the lariat, the ax, plow or perhaps the six shooter than with book and pen,” according to The Corps at Aggieland, a campus history.

Membership in the corps was compulsory, and part of the corps’s mission was to make rough, uncultivated young men into productive citizens. These guys needed the basics—in the early years, weekly baths were made a school requirement. But the corps was also a distinctly Texas institution, and when military and Texas traditions conflicted, the home team usually won. Differences between corpsmen were settled not by rank, but with a good hearty fistfight.

Within a few decades, the Aggie identity was set. The Saturday Evening Post visited Texas A&M forty years ago, and the modern reader would have no trouble recognizing the place. The photographs showed guys jawing around a campfire, guys squatting around a tractor, guys arm wrestling, guys being guys. “In spite of student strikes, hair-raising tricks, and threats to convert it into a lunatic asylum,” the Post wrote, Texas A&M “claims the most fanatic loyalty any college ever had.”

Hazing was a way of life. “Everyone’s foibles were subject to ridicule,” recalls Henry Cisneros, who was a cadet and commander of the combined bands in the sixties. He was a victim of quadding—getting stripped to his underwear and spread-eagled on the ground while cadets poured water on his genitals from an upper-story window. Such trials were a point of Aggie pride. “These were my buddies, the best friends I ever had,” Cisneros says. “The mind-set was primitive, but not in a pejorative way.” If the outside world found such antics ridiculous, Aggies like Cisneros felt that the midnight raids and forced runs taught him that failure would not be tolerated, that no excuses would be accepted—“The most profound lessons I ever learned in my life,” he says.

Females had no place in this world, and the males who attended A&M liked it that way. They were learning how to be men, and women could only be a distraction. “The social life was about as close to nonexistent as you could get,” says an alumnus who graduated in the fifties. As Aggies got cars and began dating women at other Texas campuses, another Aggie myth was born—that of the insatiably horny Ag. It was not a reputation that bothered those who bore it. “It worked for you,” explains an Aggie who graduated in the seventies. “Because Aggies are supposed to be jerkball horny guys, the only women who would talk to you were lookin’ for that.”

In general, Aggies worshipped their moms and planned to marry their high school sweethearts, and when they got lonely, they took advantage of the $8 Aggie Special at the Chicken Ranch down the road in La Grange. Sometimes women visited for dances or seminars—a Man Your Manners series offered by the Texas Women’s University in 1970 instructed Aggies in asking for dates and how to dress for them—but most of the time Aggies were left in glorious solitude. While they marched and competed and hazed one another, they could envision themselves as soldiers, statesmen, and knightly gentlemen. And no one was around to suggest they were anything but that.

“TALK TO ME ABOUT VAGINAS,” a woman on-screen is saying, while a man peers into her most private parts. “What does it feel like? Warm? Does it seem like a nice place to put your penis?” This is Professor Wendy Stock’s human sexual behavior class, a psychology course designed to teach students about proper sexual conduct as well as proper sexual functioning. Today’s film, for example, is supposed to get the group of ninety or so young men and women talking about the harm that comes from sex therapists who have sex with their patients. A discussion afterward covers AIDS, safe sex, the pleasure of giving women pleasure, and how to lessen male performance anxiety by—uh oh—“decreasing the macho image.”

After listening to her fellow students for almost a quarter of an hour, one student feels compelled to declare that Stock’s class has been invaluable to her.

“I’ve learned more in this class than in any other,” she says. Professor Stock, a slight woman with a halo of wispy brown curls and a somewhat pained demeanor, smiles wanly and offers thanks. “I think,” she says, “I’ve just had a mental orgasm.”

If Stock’s numerous enemies among Aggies past and present could hear such talk, it would only confirm their suspicion that women in general and Stock in particular are bent on destroying all that is great about Texas A&M. It is not just Stock’s class that has made her anathema to true-blue Ags but her role as the faculty advisor of the campus chapter of the National Organization for Women. Worse, Stock has become an unofficial spokesperson for the corps’s accusers in the press. Such activities led the Association of Former Students to call a press conference in which they charged that Stock was part of a conspiracy of feminists, homosexuals, and faculty to destroy the corps. A barrage of hate mail followed; things got so bad that Stock tried on a flak jacket after receiving a flyer that read, “Let the feminists and homosexuals meet me on the final review drill field where we can settle this issue!”

Such sentiments are nothing new. “I can verify that there is a priceless intangible spirit that most A&M men have, that I believe would be killed if girls are admitted,” wrote one alum in 1963, the year the school was opened to women. “We men know how to appreciate, love, and honor our women, but we also know what a fix Eve got us into in the Garden of Eden. Let’s not let it happen at A&M.” Aggies may be the only men left in America who will admit openly that women threaten their way of life and who will fight to preserve it.

Indeed, Aggies have been fighting women for decades. Ever since the thirties, when women first sought admission through the courts, the history of women at A&M has been a history of lawsuits. During the Depression, financially strapped residents of Bryan and College Station wondered why they had to send their daughters away to college when there was a state-supported university in town. The parents sued and lost. A judge ruled in favor of two women who brought another suit in 1958, but he was hung in effigy on campus and reversed on appeal. What finally forced A&M’s hand was not the law but economics. By the early sixties A&M’s enrollment lagged far behind that of UT and barely exceeded Lamar Tech’s in Beaumont. Still, it took the appointment of non-Aggies to the board of regents by Governor John Connally to force the school to move forward. When president Earl Rudder gave students the news in 1963, he was met by angry cadets shouting, “We don’t want to integrate.” Five hundred cadets marched on the Capitol in protest, and graduates sent back their rings and cut the Aggies out of their wills. “It’s a helpless feeling,” one student told the Houston Post. “You wake up one morning and you’re enrolled in a coed school.”

The corps held out for eleven more years. Finally, in 1974, fearing Justice Department intervention, A&M opened the corps to women, but even then corps organizations like the band and the color guard remained closed. That rule was challenged in 1979 by a student named Melanie Zentgraff, who sued the corps for sex discrimination after she was denied admission to the color guard and threatened by corps members for wearing senior boots. She leaked word of her experiences to nationally syndicated columnist Jack Anderson, whose story was headlined CORPS PUERILITY, NOT VIRILITY, RIDES HERD AT TEXAS A&M. The suit wasn’t settled in Zentgraff’s favor until 1985; when she graduated in 1980, university president Jarvis Miller refused to shake her hand.

Even as the school capitulated to legal decrees, it continued to treat women as second-class citizens. A&M was glacially slow to build women’s dorms, rest rooms, and locker rooms; for years, the only sports offered to women were golf and bowling, because there was no place for women to change clothes. The center of resistance to women remained the corps. When women ran for the student senate, for instance, their campaign signs in the court area were burned. “It was considered good bull to protest,” one cadet told the papers. In 1986 five cadets were found guilty of assault after they dragged a woman from her post directing traffic during bonfire preparations, which was previously reserved for males, but the school seemed deaf to warnings that such incidents were not as isolated as they seemed. A faculty senate report issued in 1991 suggested outside supervision of the corps—members had been policing themselves since President Rudder removed military personnel from the dorms as a cost-cutting measure in the sixties—and revealed that 100 percent of all female cadets felt they had been subjected to sex discrimination. Again the complaints were ignored, the tacit message being that Highway 6 runs both ways.

THE NEWSPAPER HEADLINES FOR last September and October would have been agonizing for any A&M alumnus: OUTRAGES PIERCE A&M TO ITS CORPS; TEXAS A&M SHOULD CLEAN RANKS; TEXAS A&M’S TARNISHED CORPS. The stories of assault, rape, and discrimination had a no-surprise quality for many; the cadets were simply living up to their reputation. The scandal also fit the decades-long pattern in which corps resistance seems to flare up every time a sacred Aggie tradition is broken. In this case, the story unfolded just as the university was completing another step in the coeducational process. For the previous two years, the corps had been trying to disband all exclusively female units and merge them into male ones, with varying success. The Parsons Mounted Cavalry, the group accused of assault by the woman who later recanted, was, for example, one of the units most determined to remain all male.

The trouble with the scandal was that the closer one got, the less clear it appeared: Not only was the campus split over what had actually happened—the faculty sided with the protesting women; the alumni and most of the students with the cadets—but the corps itself could not reach a consensus. Some of the men (very quietly) supported Carolyn Muckley, while some female cadets deeply resented her interference. (Some of the women’s sentiments may have been in self-defense. One sympathetic male told NOW that he had witnessed “triple the anti-Wag harassment,” since the scandal broke.)

Those who disagreed with Muckley and her supporters believed that the women had exaggerated their claims, and indeed, the wildest charges were the most difficult to prove. In one investigation, the male officer accused of beating a female cadet with an ax handle was swiftly exonerated, and in another, an examination of the charges brought by the cavalry member who accused her fellow cadets with brutality turned up no such thing. The female cadet who accused a corps member of rape decided not to press charges. The situation was ambiguous (she had gone to his room willingly, and she had had a beer that night), and corps members discouraged her. The school could not do much without her assistance. Then too, some of the events cited by Muckley occurred several years ago, and since then some improvements in the status of women have been made. There has been a tendency among the women who are protesting to fail to distinguish between small charges and larger ones; any slight tended to be used as a weapon in the sex discrimination arsenal. (One woman reported to her commanding officer that a senior had called her a “bag of shit.” The CO reported back that “he treats all freshmen the same and calls both males and females ‘bags of shit’”).

More annoying to true-blue Ags is that these women seem reluctant to embrace wholeheartedly the Aggie way as exemplified by the corps. In particular, they resist Aggie alterations of military traditions, like the endless recitations of campusology, the boys-will-be-boys antics like the “flying buzzard,” in which an upperclassman commands a freshman to spit in another upperclassman’s food. They gripe about being “crapped out,” or punished for not having a dinner knife pointed towards Kyle Field at the end of a meal, and about having to do umpteen push-ups before they can go down the hall to the rest room in the middle of the night. Aggies argue that such experiences build the kind of camaraderie and leadership necessary in wartime; and while that notion may be debatable (the military has rid itself of many such techniques), something about the corps still seems to work: Texas A&M still produces more commissioned officers than any other school outside the service academies, and its graduates have long served with distinction, most recently in Desert Storm.

But the battle of the sexes at A&M isn’t really about military readiness. The women in the corps, in fact, may be more interested in a military career than many of the men. The women are the ones who stress that A&M is the only military college in Texas and is, therefore, an important stepping-stone to a successful military career. Women who want to be soldiers join the corps because they have to: Any student, male or female, who wants to take part in ROTC must belong to the corps for the first two years. While there are males who join the corps to advance in the military, far more members are what are called drill and ceremony cadets, who join up because their fathers and grandfathers did. For them, the corps is a fraternity with a military gloss. They are drawn to the organization to test themselves against traditions established generations ago. In this striking bit of role reversal, it is the men who are locked in sentiment and the women who would be very happy to dispense with it entirely.

The reason the women don’t admire so many of those traditions is that too often the men hide behind them in their attempts to drive the women out. That is also why, ultimately, it’s the day-to-day life of the corps—as much as any headline-grabbing crisis—that is enough to dismay even the most halfhearted feminist. A school investigation of the cavalry did not turn up the brutality the original accuser had described, but it did uncover the kind of hazing that is against corps rules: Male cadets refused to talk, ride, or march with her; she was also pelted with horse manure while pushing a wheelbarrow. The woman who accused a fellow cadet of rape was belittled and criticized by ranking corpsmen. She was finally driven out of the corps and gave up her dreams of a career as an Air Force pilot; the corps held a disciplinary hearing for the man she accused (he quit the corps the day after the alleged incident), but she was never informed of the hearing.

Essentially, the male cadets and their supporters on campus believe that the women should conform to corps standards, that they should gut up and take it just like the guys do. But in many ways, the deck is stacked against women. Those who can’t live up to Aggie standards are viewed as wimps, while women who do are pegged as lesbians. And while the military may use humiliation to build discipline, the corps’s techniques are too often doled out solely on the basis of gender. One woman reported that when a corps member said he’d like some milk, another corpsman indicated a female cadet with large breasts, and announced, “We could have her pump it out for us.” In another episode, female cadets said they were told to raise their hands by putting up their “dick skinners.” Another woman was told, “Do push-ups like you want it slammed up you.” There is, too, the notorious Bag a Wag ribbon that male cadets wear after supposedly having had sex with a female cadet. Carolyn Muckley, who is part Vietnamese, says a corpsman phoned her with a threat to “rape your Viet Cong c— until it bleeds.” It is true that corpsmen call each other faggots with good-natured affection, but such epithets directed at women are neither good-natured nor affectionate, and no one could mistake their use as character building.

Members of the corps like to maintain that they treat everyone the same—that such language is just part of the trial by fire they require. But they don’t treat everyone the same, and in fact, they can’t treat everyone the same; the sexual element women have brought to the corps has changed the rules of the game, as the men always knew it would. Take quadding. Guys stripping down another guy, spread-eagling him, and pouring water on his genitals is one thing. As Henry Cisneros says, the guys who did it to him were the best friends he ever had. But guys stripping a woman down to her underwear, spread-eagling her, and pouring water on her genitals is something else entirely. Quadding a woman is a sexual assault, and it cannot be condoned. The Aggies have reached another point where some of their beloved traditions will have to go.

“IF A WOMAN REALLY WANTS TO go out there and stay up all night and get mud all over her and cuts on her hands from bailing wire and get stuff spit on her clothes, then that’s her prerogative,” one alumnus said dubiously of the women who want to help build A&M’s annual bonfire. That women want to do just that has always been the hardest thing for many Aggies to grasp. Just like me, they want to work hard and push themselves to the limit—it’s part of being an Aggie, after all. On this fall night, for example, the busy construction site that will produce the annual bonfire celebration is abuzz with male and female voices. For years, the only job women could get at bonfire was to distribute lemonade and cookies to the males who moved the logs, but now there are women in flannel shirts warming themselves near the campfire, wearing hard hats that say “Give Me Your Panties Bitch” and “F— Your Own Log” (“I borrowed it from my boyfriend,” explains one woman). Though women still don’t run the bonfire, they now do help with the heavy lifting, moving the massive logs onto the even more massive log tower that will be ignited in just a week or so. This is progress, Aggie style.

In the thick of things is junior Margine Duarte, a corps first sergeant from Nicaragua. She is a pretty woman with long, dark hair and a wide, generous mouth, someone who gives the lie to the female cadets’ Big Bertha reputation. This is Duarte’s third bonfire—in the past she has started earlier, helping, in her words, to “chop trees and push logs.” Now she comes to the site mostly to “motivate” the freshmen she supervises and because she thinks building the tower is exciting.

Duarte loves the corps. She has stayed in—even though she cannot get a military commission because she is not a U.S. citizen—hoping that the leadership skills she is developing here will help her get a job with a multinational corporation. She represents the kind of woman the men in the corps can live with. She’s not a complainer, and she has the more tolerant boys-will-be-boys attitude necessary for surviving life in the corps. (The women who accused the corps of discrimination were “insecure,” she says; the corps members pick on the most sensitive women.) At the same time, Duarte knows the score. She doesn’t date corps members (“Because I work with them, and I know what they’re like”), and she doesn’t do anything that might invite abuse. “When I walk, I walk very confident, and I want everyone to respect me so they won’t do that to me,” she says. “I’m pretty sure they do it behind my back, but as long as I don’t know about it, I don’t care.”

The question at A&M, really, is whether women should conform to the corps, as Margine Duarte has done, or whether the corps should conform to the women. The answer is that both must do both. The women have to embrace those traditions that are not debilitating, and the men have to forsake those that are.

The dream of Aggie diehards is that life in the corps can be made so unpleasant for women that eventually they will either leave the corps or stop whining. As the events of this fall have proved—to say nothing of decades of losing legal battles—this is a doomed dream. How much bad publicity can A&M withstand, how many lawsuits can it afford to lose, before it reforms the corps and moves the school that last step into the modern age? The corps will lose this fight against women, just as it has lost all the others, because it is fighting against the future. Already the latest investigating panel has recommended a plan for cadets to take leadership classes—a euphemism for sensitivity training. It has also been recommended that real military officers return to supervise the corps dorms. The number of men in the corps continues to dwindle, and if it is to survive, it will have to not just tolerate but welcome women like Margine Duarte, who can be more loyal to the corps than to her sex, who still believes in the best the Aggies have to offer—the chance to belong to something bigger than herself, the chance to practice loyalty and leadership.

“Margine, are you bored?” an officer snaps when he catches her chatting. “Help us move logs.”

Duarte excuses herself and jogs over to take her place beside her buddies, slapping on a hard hat as she goes. In unison, ten women heave a huge log onto their shoulders and haul it toward the base of the tower, just a bunch of hardworking women doing their best to send the Aggie myth shooting up in smoke.

- More About:

- Longreads

- College Station