This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

There is a certain feeling of complete and hopeless awkwardness that is most vivid during puberty but every now and then, as life goes on, it comes back in flashes. I have always felt it while looking at photographic portraits by Gittings. The world that I inhabit—a world of mismatched socks and frayed neckties—is not the world shown in Gittings portraits. I know this because, like anybody who travels around Texas, I run across Gittings’ work fairly often. In airports at Houston and San Antonio there are Gittings display cases, with portraits of the local political gentry. Gittings’ downtown display windows and the tiny Gittings shrine tucked away in the Houston tunnel system are always stocked with likenesses of dynamic business leaders. The biggest Gittings studio, in the Houston Galleria, is full of intimate living-room portraits of the great, as well as booklets with pictures of society weddings, irresistibly appealing to the voyeuristic. The people in all these pictures seem to belong to a single tribe. They are rich, purposeful, surrounded by lush furniture and beloved, manicured little dogs—people whose whole bearing is somehow tilted confidently upward, who are flawless in every detail.

Gittings portraits perfectly fit the Texas that they collectively portray: newly urban, newly rich, a place with sophistication fully in mind as a goal but not yet fully achieved. In this respect they bring to mind the odd relationship photographs have with the truth. Of all the forms of depiction, they are the most irrevocably tied to reality. A photograph is a precise record of how the tiny rectangle of territory that fell within the camera’s lens looked in the fraction of a second when the shutter was open. But it’s undeniable that Gittings portraits look a certain way. And what I always wondered was this: who was responsible for the way they looked? Was there a wizardry possessed by Gittings himself, whoever he was, that could make anybody look that way? Or did a certain percentage of the population of the world consist of people who already looked like Gittings portraits, all of whom made their way to Gittings? Or was it a combination of the two—perhaps the Gittings tribe was willed into existence by the combination of its own members’ and Gittings’ aspirations? If so, it was fair to ask what each partner in the marriage had given up to make it work. A quirkiness or sense of self-doubt on the part of the subjects that the portraits erased? An urge on the part of the photographers to show something other than successful people’s best versions of themselves?

Portrait photography in America is as old as photography in America, and it has always provided the majority of photographers with their livelihood. There is hardly a town of more than five thousand people that doesn’t have a local studio, and as a result the ancient craft of portraiture has been made accessible to almost everybody. You can’t go into the home of even a welfare mother or a migrant vegetable picker without seeing a flotilla of family portraits. For the most part, portrait photography studios are mom-and-pop operations. There are only two major exceptions: the Bachrach studios up and down the East Coast and in Chicago, and the Gittings studios in four Texas cities, Phoenix, and Atlanta.

The Bachrach studio was founded in Baltimore in 1868 by David Bachrach, a German immigrant who had been a news photographer during the Civil War. By the time of the heyday of David’s two sons, Louis and Walter, in the late twenties, Bachrach had studios in 48 cities and was the official photographer to the prosperous classes of the East Coast and the upper Midwest. Bachrach’s work was never openly artistic or avant-garde, but never obviously dated either. Attention was paid to detail. Brides by Bachrach glowed demurely, executives were solid and commanding, presidents (Bachrach has photographed every one since Andrew Johnson) concerned and trustworthy. The company took great care to photograph the leading citizens of the day, and this, of course, conveyed some sense of kinship to the everyday burghers and their families who made up the bulk of the trade. Today Bachrach is still going strong. Louis bought out Walter in 1935 and then passed the business on to his two sons, Bradford and Fabian, who recently passed it on to Fabian’s two sons, Robert and Louis. The headquarters are in Boston, and there are five studios.

Back in 1919, Paul Linwood Gittings, a poor boy born in Baltimore on the twenty-third day of the century, went to work for Bachrach as a plate boy. He became, with time, a Bachrach photographer on the road in the Midwest, in Canada, and finally, in 1928, in Texas, with studios in Houston and Dallas. Then came the stock market crash and disaster for the Bachrach organization, which decided to close 36 of its studios, including the ones in Texas. Paul Gittings persuaded the Bachrachs to sell the Texas studios to him at a sub-bargain rate and to let him operate for a year under the name “Gittings, Successor to Bachrach.” After that he was on his own.

Today Gittings and Bachrach are neck and neck—each does in the neighborhood of seven thousand portraits a year—and nobody else in the business is even close. It is impossible to avoid seeing the two studios as a parable of Frostbelt versus Sunbelt: Gittings slowly inching ahead, its work flashier and less dignified than Bachrach’s, its commitment to color more complete, its celebrity subjects the John Waynes and Barry Goldwaters and Tom Landrys of the world while Bachrach’s are Kennedys and O’Neills.

Gittings hit so big here partly because he imported the integrated system of sales, photography, processing, delivery, and advertising perfected by the Bachrachs, but purely as a photographer he was on a different level from the small operations that he quickly dominated. A few years ago a Harvard curator named Barbara Norfleet put together a book called The Champion Pig from the records of portrait photographers all over the country, including Gittings and one other studio in Texas, Harry Annas of Lockhart. The Lockhart pictures, oddly, are much closer to what people today regard as photographic art—straightforward, honest images of unadorned country people. The Gittings pictures, dating from the early days of the studio, come across as brilliant period pieces, scenes of impeccable art deco luxury in which artifice is all. It is instantly clear what the appeal of Gittings was to the citizens of the new subdivisions of River Oaks and Highland Park: he could show them as they preferred to think of themselves. And because he charged more than the other photographers (today the rates run from $75 for an assortment of three black and white prints up to $2500 for a forty-by-fifty-inch canvas-mounted color portrait), he could afford fancier studios, advertising programs that were more splendid, and closer attention to detail in the actual photography.

In the opinion of everybody connected with Gittings, this attention to detail is the sole distinguishing characteristic of the studio’s work; they say Gittings portraits are uniformly marked by a high degree of technical precision, rather than a vision or even a sensibility. “Our photographs have a quality about them,” says Arthur Heitzman, Gittings’ director of photography, “but it’s difficult to define. It’s the standard of quality that we maintain. We schedule a full hour in the studio and two hours when we shoot on location. Our photographers go through a very rigid training program that takes from two to four years. They’re evaluated every year in each of fifteen categories. For example, one of Gittings’ strengths is that we really stress hands. Most photographers hate hands. We understand them. A bad hand, with the fingers spread, looks awful, like a cow’s udder. We had wooden pegs made up for the subjects to hold. Or they can hold their glasses. It creates nice curves. And the feet are important too. If the feet aren’t right, it screws up the hands.”

As Heitzman was explaining this to me, we were wandering through the Galleria studio looking at what was hanging on the walls. In the position of honor in the reception area was a picture that I would have known was a Gittings had I come upon it hanging in the Louvre, and not because of its technical perfection, either. It was a Gittings in its soul. It was a group portrait of the family of Vincent Kickerillo, the penniless child of Italian immigrants who made good—extremely good—as a homebuilder in Houston and then became a banker and developer. He was wearing a radiant off-white suit with a white pin-striped shirt and a striped tie; his bejeweled wife, for whom (according to rumor) he once built a full-scale recording studio, was in a diaphanous white dress with flowers; their young daughter wore an immaculate white sailor dress and white shoes. They were in a living room of great luxury, a Renaissance bronze to their right, heavily curtained floor-to-ceiling windows behind them. Near the Kickerillos’ portrait was one of Joanne King Herring in a floor-length chiffon gown adorned with silk roses, standing amid a fabulous array of antiques, the gilt portions of which had been rid of their patina and brought to a gleaming polish. A little ways away were Sophia Loren, looking décolletée; Red Adair, dressed in a jump suit, the scars of a thousand oil well fires artfully softened; and the Duke. Down the hall was Lee Trevino.

Heitzman took me out of the reception area, past the offices of the salesmen who make appointments with subjects, and into the studios. Like all photographic studios, they looked nothing at all like they do in the pictures. The burgundy-toned libraries familiar to me from the portraits of men were really linoleum-tiled rooms with sliding backdrops and shelves of real books mixed with fake ones. The children’s playrooms were a stage set festooned with toys. There was a women’s area too, a corner done up in soft tones, testament to the harsh reality that in the portrait photography business, women are different. They’re still photographed with four-by-five (that is, large enough to be retouched) negatives and often with a lens called an Imagon, which softens the picture. As one Gittings brochure puts it, in the studio’s characteristically euphemistic prose: “In portraits of women, the camera does occasionally tell half-truths. Therefore, a degree of softness in some places is most flattering. Additionally, a moderate amount of refinement can be applied on finer qualities.”

Somehow everything about the studio, even the unconsciousness of the style and message of its own work, conveyed a genius for commerce. There was the artful mix of its clientele: the small group of celebrities (have I forgotten to mention Princess Grace, Pat Boone, Gene Tierney, Nancy Reagan, and John Connally?); the middle range, made up of big-shot Texas regulars (the entire membership of the Houston Petroleum Club, many generations of the Bentsen family); and the mass of ordinary middle-class folks—brides, kids posing for annual pictures, executives who need to keep handy an official photograph of themselves. There was the peculiar trendiness of the portraiture, which made it possible to tell almost to the year when each one was made because of the telltale presence of a miniskirt or a crew cut; like good retail products, but unlike art, old Gittings portraits seem dated, more valuable as historical documents than as repositories of beauty and truth. There was the flair for promotion: “The Proud Years Soon Pass,” Gittings billboards once reminded the middle-aged, with oddly combined bluntness and good taste. There was an air of obvious sincerity, like that in The Sound of Music, about the place. It seemed that behind the whole operation lay the sensibilities of a consummate businessman.

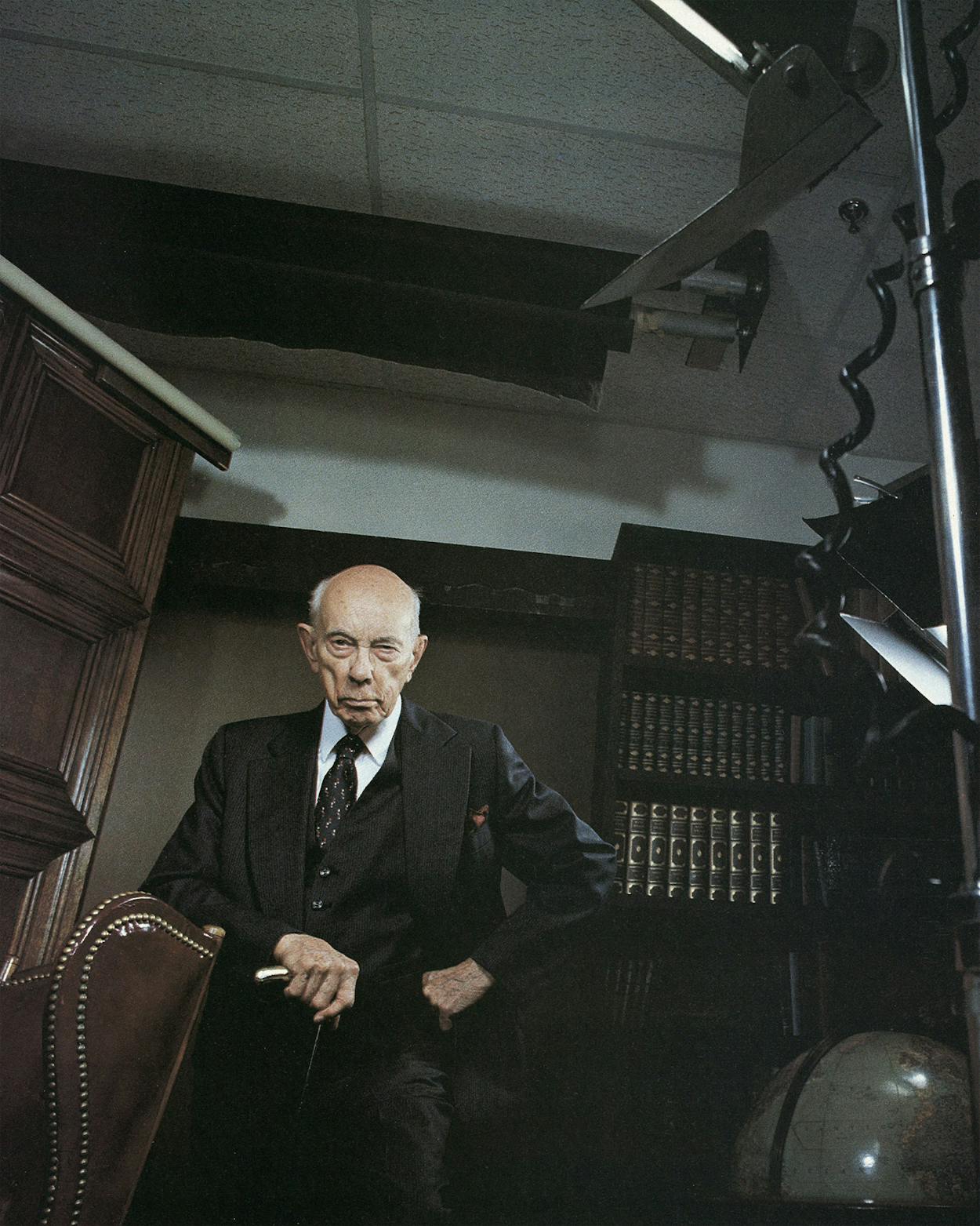

But when I met Paul Linwood Gittings, he presented himself to me as an artist. He is retired now, living in a condominium on Northwest Highway in Dallas; his daughter, Myrl, runs the Gittings Texas offices and his son, Paul Junior, the out-of-state branches. He was elegantly dressed in a blue suit with a natty handkerchief in the pocket on the day that I called on him, and he pulled down from his shelves a leather-bound book with his name inscribed on the front in gilt letters and leafed through it with me. It was a collection of what he considered the finest work of his career, made up in part, to my surprise, of figure studies of female nudes.

Mr. Gittings didn’t want me to get the wrong impression. “I never used anybody but models,” he said. “And I always had somebody else there in the studio, to make sure I handled myself as a gentleman.” He said that he took pains to ensure that the women were not recognizable, and he showed their pictures only to other serious photographers, never to the general public, who wouldn’t understand. It was plain that the female form entranced him. He showed me how he had tilted the negatives slightly to create artful lines and forms, how light and shadow interplayed in his work. The nudes themselves were technically flawless, exposed only to the modest extent common in World War II pinups and, on the lowbrow-highbrow scale, aimed at the upper middle. “Figure studies are the most difficult kind of photography,” Mr. Gittings told me. “Only three men in the United States could do them with taste and delicacy.” We went on through the book. “This was the beginning of my acceptance into the fine arts world,” he said, stopping at a profile of a Hockaday graduate he’d done in 1930. He turned some more pages. “I call that one the green goddess,” he said, stopping to look at one, and then he went on until another caught his eye. “This picture,” he said, “is the most intimate portrait ever made. You get an intimacy here that you usually get only when you . . . kiss a woman.” Laying the book aside, he told me about the photography salons where he’d hung his work, about his membership in the world’s four most prestigious photographic societies, about the museums where his work had hung, about Karsh and Fassbender and Steichen. “I’m the last of the Mohicans,” he said.

At the age of eleven, Mr. Gittings had left school and gone to work to help support his father, who was blind. He had been an office boy, a munitions factory worker, a waiter, and a streetcar motorman by the time he got to Bachrach. Even as a full-fledged Bachrach photographer he had a strikingly tough life. In an autobiography he published in 1968, he describes pawning his wife’s engagement ring in La Crosse, Wisconsin, to buy her a set of warm clothes, running out of money again, being reduced to a diet of apples, and, finally, Evelyn Gittings’ losing their first baby in a cheap furnished room in Quincy, Illinois, while he was out shooting portraits. Mr. Gittings had both the hunger to appear cultured that is common among the unschooled and the hunger to get on in the world that comes from having grown up poor, and, as he told the story, at the age of fifty the latter won out and he decided to put business ahead of art. He had at that point been in business for decades already, but never, he said, with all his heart and soul and therefore never to the point of prosperity. But in 1950 he charged into color photography and all-out promotion, and he became a well-to-do man.

“I did sacrifice art for business,” he said. “I made up my mind to use photography as a business tool, and I was unusual in that I was good at business as well as photography. But as time went on, I realized I’d never had that one fine point in the arts that would make me stand out. Besides, I couldn’t make a living. So I went at it from a business angle. You know, all the people from photography school want to photograph young, good-looking girls. Well, they haven’t got the money! The older people have got the money.” He put it more pointedly in his book: “Hundreds of men, busy with stained fingers, worked day after day making and selling maps of people’s faces on photographic paper. They envied the few who succeeded and were blind to the product they sold in their own studios. The photographer doesn’t sell photographs; he sells sentiment and flattery. From the day that he fully understands the philosophy of the product he sells and bends his efforts to that end alone, he will prosper.”

In describing his transformation from artist to businessman, Mr. Gittings stood firm as a rock on the point of his craftsmanship. “The Gittings style is not exaggerated,” he said. “It’s subtle. We just don’t overdo things. That’s an important part of the Gittings look. We make people look sophisticated. We always kept abreast of things, but we didn’t overdo things. I was a good merchant. I did a lot of things that would give me publicity. The leading people learned to know me and I learned to know them. But I never used my knowledge of people to get their business. I didn’t socialize with them. After all, with my background I’d have had a pretty hard time. I was a nobody from nowhere. I had nothing to recommend me but the quality of my work and the integrity of my name.”

Mr. Gittings himself could be thought of on one level as a Gittings portrait. He looked terrific. Nothing was out of place. He carried himself with majestic dignity and self-confidence, but at the same time he was not so perfect as to be off-putting. On another level, though, he was not a Gittings portrait. He made no effort to camouflage his hurts and disappointments; he did not pretend that the way he appeared was identical to the sum of his ambitions. He had a complexity that a Gittings portrait would not show. That he could have produced so many thousands of Gittings portraits was a sign of the presence of something beyond the combination of his own skills and yearnings. But there had to be yearnings in his subjects too.

One day I went to the Gittings studio in downtown Houston to have my portrait made. I was instantly in good company. Mayor Whitmire’s likeness greeted me on one side of the entry way, and on the other were successful businessmen—Ben Love, Michel Halbouty, David Saxon. Bob Hope and George Brown gazed down from the walls inside. I settled some business details with a clerk and then was sent into a dressing room stocked with a razor and shaving cream, hair spray, a discreetly masculine box of makeup, and a portrait of Miguel Aleman, former president of Mexico. I combed my hair and went into the studio, an empty room with a variety of props and backdrops cluttered at one end. My photographer, a young man in a three-piece suit named Steve Schroeder, came in and introduced himself, and we immediately struck up a determined and good-humored friendship. Tomorrow, he said, he would be shooting the Moody family of Galveston.

Steve began guiding me through a series of poses. I would sit at a fake desk, then stand next to a plush leather chair. A white backdrop would be maneuvered behind me, then a brown one, then an oaken door, then fake bookshelves. Steve was constantly adjusting the lights and my pose. I was instructed to lean forward, to hold my glasses loosely in my hand, to put my pen and reporter’s notebook in front of me on the fake desk, to hike up my knees and adjust my feet. Before every shot I was put through an odd exercise in which I would first tilt my head to the right and then thrust my chin upward, the result being a funny-feeling pose that I knew would produce the winning je ne sais quoi common to portraits of successful executives. All the while Steve endeavored manfully to keep up a pleasant banter between us (“So . . . have any pets, Nick?”), without much help from me.

I make it sound like an awkward experience, and in a way it was, but as the session went on I realized that the whole thing was going to work. Thanks to Steve, and to all his tools, the lights and the backdrops and the props, I really was going to be a Gittings portrait that looked like other Gittings portraits. In all honesty, much of the credit for the success of the endeavor was due to me. I had cooperated nicely during the session; I had dressed conventionally and put on a new tie. I found I had it within me to play the part; that made me feel warm, mature, sensible. I thought of how Mr. Gittings must have felt when he decided to concentrate on commerce rather than art. In my own small way, I was a similar case. Like everybody else, I had off and on toyed with unconventionality in the name of creative self-expression, but now I was willing to lay that aside because of the growing strength of my desire to become a Gittings portrait. Whichever of my quirks were going to be missing from my portrait were probably good riddance anyway. I felt different.

As I left the studio they told me it would take a couple of weeks for my sample shots to arrive, but that was okay. I knew the results wouldn’t surprise me. On the way out I nodded good day to Bob and Kathy and Ben and George. I was one of them now.

- More About:

- Art

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- Houston