Where do songs come from? Can the songwriter take full credit for what he’s made, or is he in part just a conduit for some greater creative power? In a new exhibition at the Blanton Museum of Art, part of the University of Texas at Austin, the outlaw country singer-songwriter and visual artist Terry Allen compares the people and events in his life that have inspired songs to figures in older religious paintings depicted with holy flames above their heads. Such figures are typically saints, whereas Allen’s songs are more often populated by sinners, pillheads, and maladjusted Vietnam vets, but you get the idea. It all hearkens to the same mystery of divine revelation.

The Blanton show, up through July 2022 and titled with the pun “Terry Allen: MemWars,” brought to mind various memoirs by aging musicians that have crossed my transom in recent decades, from epic but straight-ahead autobiographies by Willie Nelson and Keith Richards to more literary, oddball, and voice-driven books by Patti Smith and Bob Dylan. It’s in keeping with the uncategorizable talents and art-cult celebrity of the 78-year-old Allen that he has chosen to share his back pages in an even more unusual and more genre-defying format: a multimedia gallery installation. It works, though—at least for those with the patience to sit through an hour-and-a-half-long video and spend a good deal of time reading through the text-heavy wall collages in an adjoining room.

The show should be seen as a pilgrimage destination for die-hard Allen fans and an appealing point of access for those just getting curious about his life and work. Even those who only know one song of Allen’s—likely “Amarillo Highway” from his 1979 Lubbock (On Everything) album—will be treated, in the video portion of the exhibition, to an irresistible story of that song’s origins. As a kid, Allen would drive up to Amarillo for fried chicken dinners with his extended family, after which his uncles would gather around the dining table to plot robberies of local banks, using real blueprints of the banks in question, arguing over details like what firearms and explosives to carry and who would drive the getaway car. As far as Allen knows, none of the banks were ever actually robbed. He characterizes the sessions as “a game, like Monopoly or Clue—I think.”

Allen’s memories sparkle with the one-of-a-kind aura of art objects. Each is precious to him, and we feel the mysterious ways they intersect with his songwriting craft. Whereas the narrative engine of a book-length memoir requires a broad (and too often false and forced) sense of causality, arc, and building stakes, here each recollection only needs to carry its own weight, floating in its unique moment. Most importantly, Allen’s memories are not required to cohere into a story in which he himself is the protagonist—a role he tends to artfully avoid in his character-driven songwriting.

In the late nineties, the cable television network VH1 introduced a popular hour-long show called VH1 Storytellers, on which famous musicians would play a set and introduce each song by talking about its origins. That’s the most obvious analogue for MemWars, the full-room video installation in the exhibition, which follows a similar format, though Allen takes the basic-cable concept into his own hands with a few art-world flourishes. It’s a multichannel installation, with video projected on three walls. The storytelling interludes between songs are scripted and split between Allen and his wife of six decades, Jo Harvey Allen. Each speaks into a separate camera, and these two videos are projected on opposite walls, so that museum visitors enter into the space of their conversation. When it’s time to play a song, a new projection appears on the far wall, featuring a musical performance by Allen and various bits of archival footage, from a Vietnam War firefight to a dancing amputee to a long tracking shot of a High Plains highway.

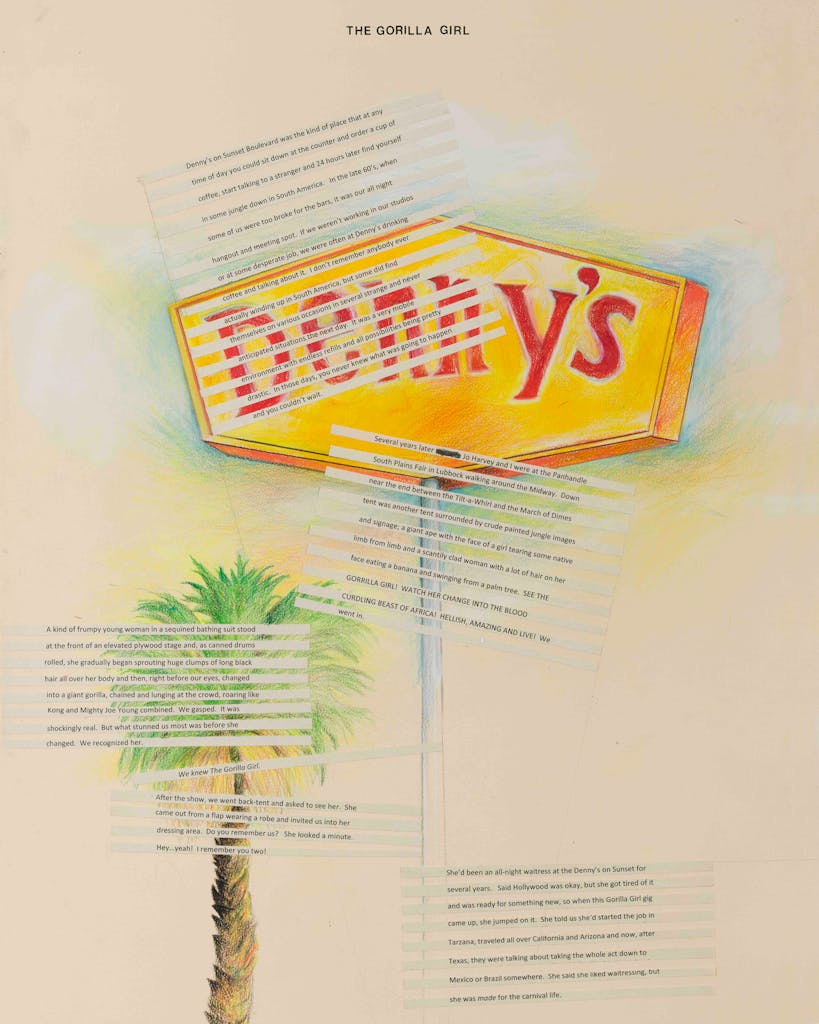

The 22 artworks on paper in the adjoining room—mostly drawings in pastel, gouache, graphite, and colored pencil with pasted-on lines of printed type—look like a cross between illustrated poems by William Blake and coming-attractions posters outside a small-town movie theater. Most contain text at least partially narrating an anecdote from Allen’s life. We learn about the waitress at the all-night Denny’s he used to frequent on Sunset Boulevard in Los Angeles, whom he ran into years later when she was performing as the hairy-bodied, ferocious “Gorilla Girl” at the Panhandle South Plains Fair in Lubbock. We get a cryptic memory of Allen as a young man pulled out of a movie theater and, with his bike thrown in the back of a police car, delivered to his parents’ doorstep, for a reason Allen doesn’t share. We get a snapshot of Allen’s grandfather, who, after taking the boy to see The Ten Commandments, pronounces, “That was the greatest picture show that could ever be made by a human man on this earth, and there is no need to ever see another one,” so he never does.

The Vietnam War comes up again and again throughout the exhibition—Allen was in his twenties at the time and working on his earliest music—including in a couple of the paper works: Little Green Men, a sort of prose poem about a kid playing with toy soldiers and enacting the whole history of human slaughter and Hollywood’s glorification thereof, and Roadrunner, about a guy Allen knew from his rowdy teenage days in Lubbock who was killed in Vietnam and who inspired his song “Blue Asian Reds.” The language from these two works is repeated in the video installation, alongside a few other war-related tales. For instance, in exploring the origins of his song “Yo Ho Ho/Big Ol’ White Boys,” Allen recalls family get-togethers during which his male relatives, mostly Navy veterans, would get drunk, show off their tattoos, and share tales of war and loose women overseas. Allen says he loved looking at the tattoos, his “first seduction” into a lifelong passion for the visual arts.

“Some call me high hand / And some call me low hand / But I’m holding what I am—the wheel,” Allen sings on “Amarillo Highway.” It’s a line that starts out as a poker metaphor but ends up speaking to the unique place Allen occupies on the vanishing overlap of highbrow art-world pretensions and lowbrow AM-radio populism. That’s a rare and tenuous posture these days, in a culture riven by increasingly fractious class and political identities defined around elitism and anti-elitism, but Allen always somehow manages to be both. More than that, alongside allies such as Dave Hickey, the great Texas-born art critic who passed away in November, Allen helped set a windows-down, open-minded intellectual mood that redefined Texas culture in the seventies. (Though he doesn’t discuss it in “MemWars,” Allen dedicated “Amarillo Highway” to Hickey.) Both men pushed beyond tired old cowboy mythologies toward a new kind of shit-kicker sophistication. It’s a liberating state of mind that we could use more of now, in art and life.

“I don’t wear no Stetson / But I’m willin’ to bet, son / That I’m as big a Texan as you are” is another classic “Amarillo Highway” line. Authentic but never quite confessional, truth-seeking but never exclusively nonfictional, and emotionally moving without the navel-gazing of autobiography, “Terry Allen: MemWars” traces the outlines of one Texas life and the origins of a distinctive voice that grew to speak to and for many others.