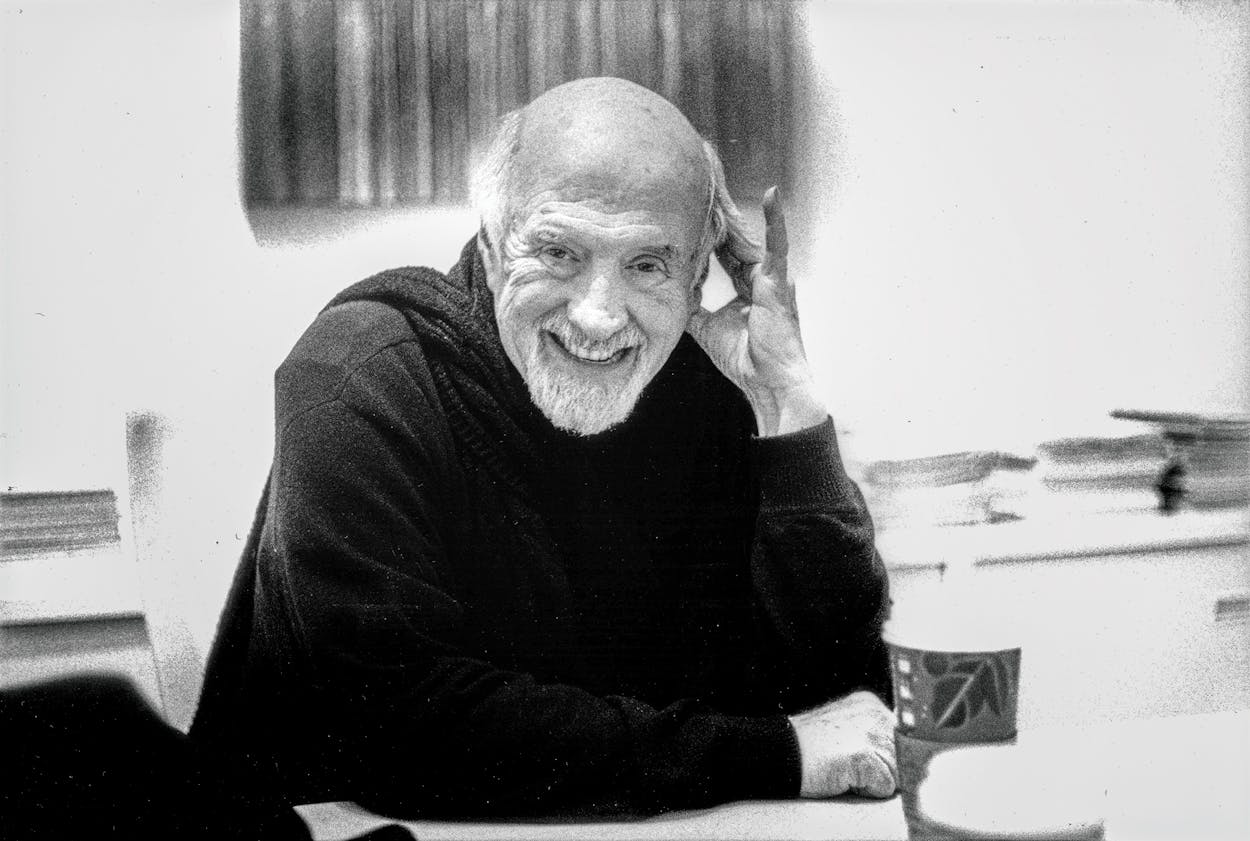

In the years I spent writing my book on the great art critic and essayist Dave Hickey, who died November 12 at the age of 82, he got really annoyed with me twice. The first time was early in our relationship, when he thought I was trying to get money out of him (long story). The second was when I sent him the final cover design of my book, Far From Respectable: Dave Hickey and His Art. It featured a photo of him in a cowboy hat.

The pic was taken in 1972 by his old friend, musician and artist Terry Allen, at the Dripping Springs Reunion concert. Dave was there because he had been asked to help organize the now-legendary festival. Allen was there to perform.

“I don’t know why he was the organizer,” Allen says. “I thought he did a great job, and then he felt bad for the people who didn’t get paid, and so he paid us out of his own pocket. I think Hank Snow was the only one who ended up making any money, because he demanded his money up front.”

The photo captures some of this generosity and sensitivity. The expression on Dave’s face, visible even through the sunglasses he’s wearing, is vulnerable. He looks uncertain and open to the world. In almost every other photo of him I found, he looked either too sure of himself or too awkward. But this one, I thought, captured something important that cut against the public persona he’d acquired over the decades, as the “bad boy” of American art criticism. At the heart of his endeavor as a writer, I believed, was an attempt at connection and communion. The photo conveyed that. Also, I was publishing with the University of Texas Press, so, y’know … cowboys.

Dave hated it.

“I’ve spent my whole f__ing life trying to get away from people thinking I’m a f__ing cowboy,” he said.

I was surprised, but shouldn’t have been. Like so many Texan artists before and after him, he had a tortured relationship with his home state and its mythology. He kept trying to get away from the cowboy thing. It kept sucking him back in.

There was another picture of him, from the fall of that same year, that he wanted me to use for the cover. It was at a gala at the Art Museum of South Texas, in Corpus Christi, and he is wearing a tux and smoking a ciggie. He looks quite debonair, like he’s out for an evening with Dean, Frank, and Sammy. He might be in Texas, but he’s not entirely of it. That was his image of himself, and what he wanted the world to see. I was sympathetic, and I hated to disappoint him. But among the many things his writing had taught me was that in the end I had to listen to my own writerly gut, and filter out other people’s expectations. So the cowboy stayed, and eventually he (mostly) let it go.

Read: Dave Hickey on Being an Art Critic

That tension between the cowboy and the sophisticate characterized both Dave’s life and his feelings about his home state. Born in Fort Worth in 1938, the oldest of three, to a frustrated jazz musician father and a frustrated painter mother, he had a Huck Finn childhood, for good and for ill. The family moved often, following his father’s jobs in distribution warehouses and car dealerships. Most of the jobs were in Texas, but there were also stops in Oklahoma, Louisiana, and Southern California.

His parents didn’t like each other much, and weren’t very focused on parenting, so Dave grew adept at finding havens from his unhappy home. He haunted bookstores and record stores, libraries and movie theaters. During the year the family spent in Southern California, he learned to surf, and would spend long days hitchhiking up and down the coast, using a Coast Guard map and some intuitive oceanographics to find the best waves. After an epic surfing stunt landed him in the hospital, his parents took his prized board, Milton Rouge, which he’d named after a beloved dog his mother had accidentally run over and killed, and threw it out.

“I felt as if something had been amputated,” he later wrote. “That was the board upon which I rode the ride, and there was nothing I could say. So I swore to have my revenge. Like the Count of Monte Cristo, I kept my own counsel. They had killed Milton the terrier, my alter ego. They had killed Milton Rouge, my oceangoing avatar. There would be an accounting soon enough, and today every word I write, I guess, is part of that revenge.”

The Hickey family came back to Fort Worth for good in 1954, so that his mother could help her parents run the family store, Balch’s Flowers. The following year, when Dave was sixteen, his dad shot and killed himself in the garage of the house the family was renting. It ended even the semblance of domestic life. Dave moved into the back apartment of his grandparents’ home while his mother took the younger kids to live with her nearby. He did his own thing until college at Texas Christian University.

Over the many decades that followed, his feelings about Texas always had a guarded edge to them, which sometimes tipped into active hostility. “I can’t tell hurt from hate,” he wrote in this magazine in 2015. In his more forgiving moments, Dave saw Texas as a place of extraordinary energy and openness, and could write about it with affection and perspective. I think he had the easiest time seeing the state clearly when he was writing in exile, first in New York, where he spent the early seventies, then in Nashville, where he did a tour in the mid-seventies, and then in Las Vegas, where he taught and wrote in the nineties and aughts.

“Which isn’t to say that Texas is a nice place,” he wrote in 1972, not long after he left for the first time. “It isn’t. But home, in the twentieth century, is less where your heart is, than where you understand the sons-of-bitches. Especially in Texas, where it is the vitality of the sons-of-bitches which makes everything possible, where there is more voracious mercantile energy, more vanity and more pretentiousness than anyplace I’ve been—excepting Manhattan. Of such stuff are cultural communities made. Chicago has the energy, and California has the vanity, but you need both: the money first and then the guts and inclination to dump it into dumb things like Art and Astrodomes—because then, even without money, there are extravagant risks which can be taken—on the chance that they will make art. More often, of course, they only make a splash of chrome and flesh across some highway intersection—like a butterfly across a windshield. But it is that sense of possibility, which has been able to sustain itself, that I most value.”

Read: Michael Hall’s 2000 profile of Hickey

One might wonder whether the pro-Texas narrative that Dave spun in his fonder moments is any more real than the pro-Texas mythos he always hated. Dave was clear-eyed about Texas’s cowboy delusions, but he might’ve been too hopeful that there was another, vastly more interesting Texas beneath that veneer. “A cosmopolitan place,” as he said to me, “although Texans like to pretend that they’re all down at Luckenbach.”

The cosmopolitan Texas that Dave conjured in his writing was born from his best few years in the state, from 1967 to 1971, when he quit his doctoral program in linguistics at UT-Austin and opened a small art gallery with his then-wife Mary Jane. During that time in Austin, until his success with the gallery enabled the move to New York, everything was in alignment for him. He got to partake in the counterculture with artists and musicians. He was immersed in the intellectual vitality of the university. He had a partner who supported and anchored him. And he had a job that he liked.

“We repainted walls perpetually and burned our fingers on the lights,” he wrote. “We typed labels, hung exhibitions, kept books, mailed invitations, and served cheap champagne in plastic glasses to the locals. We were twenty-six years old. We sold works of art by artists who were twenty-six years old (and maybe a little younger) to collectors who were twenty-six years old (and maybe a little older). … I was also in business, a shopkeeper. So I could sit around at the coffee shop down on Congress Avenue, talk cash flow and receivables, and complain about the assholes in the State Comptroller’s office. And it may sound stupid, but after the hothouse babble of graduate school, I actually felt like I was living in the world.”

When he moved to New York in 1971, the delicate constellation of forces that kept him in a stable orbit rapidly lost its hold. He blew up his marriage. He burned through a few jobs. He began using drugs more recklessly. He wouldn’t really get it back together for another two decades or so, after he married the art historian Libby Lumpkin and got a job teaching at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. That’s also when, not coincidentally, he found his groove as a writer. The two collections of essays he published in the 1990s, The Invisible Dragon: Four Essays on Beauty and Air Guitar: Essays on Art & Democracy, were extraordinary, some of the best writing on art and culture that any American has ever done.

I encountered him through Air Guitar, which my brother pushed into my hands when I was just out of college. Although it is often thought of as a Vegas book, Texas is all over it too. Along with insights on Liberace, Siegfried & Roy, and the Strip, we get stories of Dave reading Flaubert in Fort Worth, running the art gallery in Austin, road-tripping with the great Texas magazine writer Grover Lewis, and sipping beer in El Paso with the sculptor Luis Jiménez. We get him ragging on “creepy, prissy Dallas,” rhapsodizing about the walk-in refrigerator in his grandparents’ flower shop, and remembering the ecstatic shock of seeing an experimental Andy Warhol film at “Undergound Flick Nite” on the drag in Austin in the mid-sixties. “Imagine Mystery Science Theater 3000 with a hot Texas mise en scène: The clatter of the projector in the glimmering darkness. Smoke curling up through the silvered ambiance. Insects swooping. The ongoing murmur of impudent commentary from the audience. References to Althusser, Marcuse, group sex. Like that.”

My favorite piece in Air Guitar—in all his work, actually—is “My Weimar,” which is a paean to Walther Volbach, his theater professor at Texas Christian. In just a few pages about Volbach, who fled the Nazis all the way to Fort Worth, the essay conveys most of what you need to know about Dave, his feelings about Texas, and his vision of what kind of world he wants to live in.

“Volbach’s idea of art was something flexed and rigorous,” he wrote, “full of edges and bright lights—something smart that made your pants crackle. And he was such a tough old bird! Mean as a snake when aroused, but you couldn’t hate him for it. He treated you like you were supposed to get out there and do something. He told me I was a callow redneck with all the spirituality of a toilet-seat—that I could possibly cure the former but would probably have to live with the latter—but that was great! Nobody had ever told me I was anything before, so I took it to heart.”

Dave’s last stretch in Texas, from 1978 to 1987, wasn’t a happy one, but it may have been a necessary interlude. After way too much partying with outlaw country singers in Nashville, he retreated back to his mother’s Fort Worth house with a bad case of pneumonia and a months-long hangover. “I was so f__ed up I couldn’t follow the plot in I Dream of Jeannie. I’d been living on uppers and downers forever. I was in terrible shape.” Over the next decade he slowly, haltingly built himself back up. He did a short stint as art critic for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, wrote some exhibition catalogs for museums and galleries in town, wrote a lot of pop songs that no one ever recorded, and did fewer (though not zero) drugs. His mother died, leaving him a little bit of money, and he moved in with Susan Freudenheim, who was a curator at the Fort Worth Art Museum.

“I think there were a lot of bad memories associated with Texas for Dave,” says Freudenheim. “Feelings of rejection, of not being cool enough. His father dying. His mother’s struggles. Lots to love, lots to hate.”

His relationship with Freudenheim didn’t survive their move to San Diego, in 1987, but she remained fond of him until the end of his life, as did his first wife Mary Jane and his main Nashville flame, the country singer Marshall Chapman.

“Dave and I were like Bonnie and Clyde,” says Chapman. “I tried to push him in front of a city bus once. Dave was high, and I was trying to get it together for a show, and he was driving me crazy. The old amphetamine motormouth. ‘Okay,’ I thought to myself. ‘We are out on this curb. If I time this just right, that bus’s front curbside tire is going to run over his head, crushing his jaw, and I’m not going to have to listen to this s—t anymore.’ I was a little late, the bus was a little fast, so he bounced off the side of the bus. I still love Dave, though. His brilliance. He got it. He would see things on a level that nobody else could see.”

Read: Hickey’s Risk-Taking Austin Gallery That Changed the Face of Texas Art

On his way out of Fort Worth, Dave wrote a wry and deceptively nuanced portrait of the city for the Texas Observer. In his description, it was a place of profound loneliness and alienation, “a piece of West Texas, kinda bunched up to keep it from spilling over into Dallas.” There was an upside to the alienation, however. In the empty spaces where community and coherence would otherwise reside, artists, musicians, and other freethinkers had the psychological freedom to craft their own visions of how the world should be.

“On the whole,” Dave wrote, “Fort Worth is not a bad place to live, if you bring a friend. And since there are better pictures in the museums and better bands in the bars, it’s certainly preferable to its adjacent metropolis. Also, in Fort Worth and Tarrant County, being an asshole is optional—although it remains a very popular elective.”

Dave maintained a strong connection to Texas after he left in 1987. He had a lot of good friends in Austin, in particular, and would often come back to visit, speak at UT, or go to a show. He was briefly in talks with the Harry Ransom Center about the prospect of its purchasing his papers, though nothing came of it.

Toward the very end of his life, which is when I knew him, the things he didn’t like about Texas began to loom larger than the things he did like, and the salience of his early struggles seemed to intensify rather than attenuate. “I just wanted to get out,” he said to me more than once.

I never doubted the truth of that sentiment, nor that he had good reason for it. Texas is a tough place for a sensitive soul. But it was more complicated than that. He was often depressed in his last years, after his exile from Vegas. That colored his feelings about a lot of things. He was also terribly disappointed with how America had turned out since the sixties, and Texas was no exception. He felt like we’d gotten so much more square, more orderly, more boring, less cosmopolitan.

I think he also realized, as he neared the end, that he may have lost the war he’d been fighting for so long against the mythos of Texas. And I was one of the conspirators in his defeat, with my UT Press–published book and my cowboy hat cover. If he was going to be remembered and read at all, after he died, the experience was often going to be inflected by what he once described as the “scarlet T burned into my forehead.”

Texas was going to win, in other words. You can’t escape the cowboy thing. At best, you can only reimagine what it means. That wasn’t enough for Dave, which makes me a bit sad. But it was more than enough for me, and for so many other Texan readers and friends of his.

Along with everything else he gave us, he proffered a vision of our state that could accomodate as eccentric and brilliant and cosmpolitan a figure as Dave Hickey. The cowboy and the sophisticate. The smash-mouth kid from Fort Worth, the Warhol-watching hipster from Austin, and the crotchety old guy in exile who doesn’t have a nice word to say about Texas or anything in its vicinity.

I don’t know if it’s real, this vision of Texas. I don’t know what real is. But I have no question that the Texas of my mind, the one I’ve been living in for these past fifteen years, is far richer and more interesting for what Dave wrote about it. It will stay with me, modulating my perceptions, until the end of my life. I’ll miss him, but in that sense, at least, I won’t lose him.

- More About:

- Art

- Obituaries

- Fort Worth

- Austin