This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Last year, after the Battle of Flowers parade (the central event of Fiesta San Antonio) Mayor Lila Cockrell’s limousine was mired hopelessly in traffic. The mayor was trapped on a narrow side street, and not a car was moving.

Except one. King Antonio LVI—resplendent with a plumed hat, long red cape, chestful of medals, and city-block-long police escort—zipped past the mayor’s car in a lane reserved especially for him. Antonio’s realm may have been puny compared to, say, the Hapsburgs’, who once ruled San Antonio. His reign extended only to the ten days of Fiesta, after which the mayor would still be the mayor, while the king would go back to tending his tire store. But even in a make-believe kingdom rank has its privileges, and in San Antonio kings still outrank mayors.

Fiesta is the axis around which San Antonio turns. Poor people save up for Fiesta. Rich people rest up for Fiesta. Hotel people build up for Fiesta. Shopkeepers stock up for Fiesta. Garbage collectors pick up and jet-setters pack up after Fiesta. And during Fiesta every April, San Antonio is possibly the world’s most enchanting party, a gentle, unfrenzied Mardi Gras. Along the Riverwalk, a meandering garden of colored lights and hibiscus, the mariachis are out in force, tourists crowd the outdoor restaurants, and hundreds more dine up and down the river itself—on red and yellow motor barges illuminated by candlelight and festooned with giant paper flowers.

In La Villita, the little town of eighteenth-century Spanish settlers, 30,000 revelers a night cram the narrow stone streets for the foods and music of Fiesta—A Night in Old San Antonio. Cascarones, confetti-filled eggshells, spill their loads on every head. On a platform above the throng, Chicano women in colorful costumes pat tortillas into shape, and their methodical rhythms form a counterpoint to the plaintive flamenco rhythms and the spirited Mexican rhythms of the folkloric dancers across the way. Elsewhere there are country swing and country rock and dixieland, and everywhere an amber Niagara of beer cascades down 30,000 throats, rises again to 30,000 heads, and swells to a tide of benign drunkenness.

The vacant hulk of HemisFair ’68 is peopled again for Fiesta. The Skyride and the carnival are back in business. A Mexican dance band performs free, courtesy of the city. There’s more food and music, here with a Western slant, at the Jaycees’ La Semana.

Across town, a sprawling, wonderfully raunchy carnival springs up on an urban renewal wasteland. Nearby, El Mercado, the refurbished old marketplace, bustles with church-group taco sellers and souvenir hunters. At Mi Tierra, the legendary all-night restaurant, local gentry in formal clothes and ordinary people in casual clothes file past the long counter laden with sweet Mexican breads; and the mariachis play all night long.

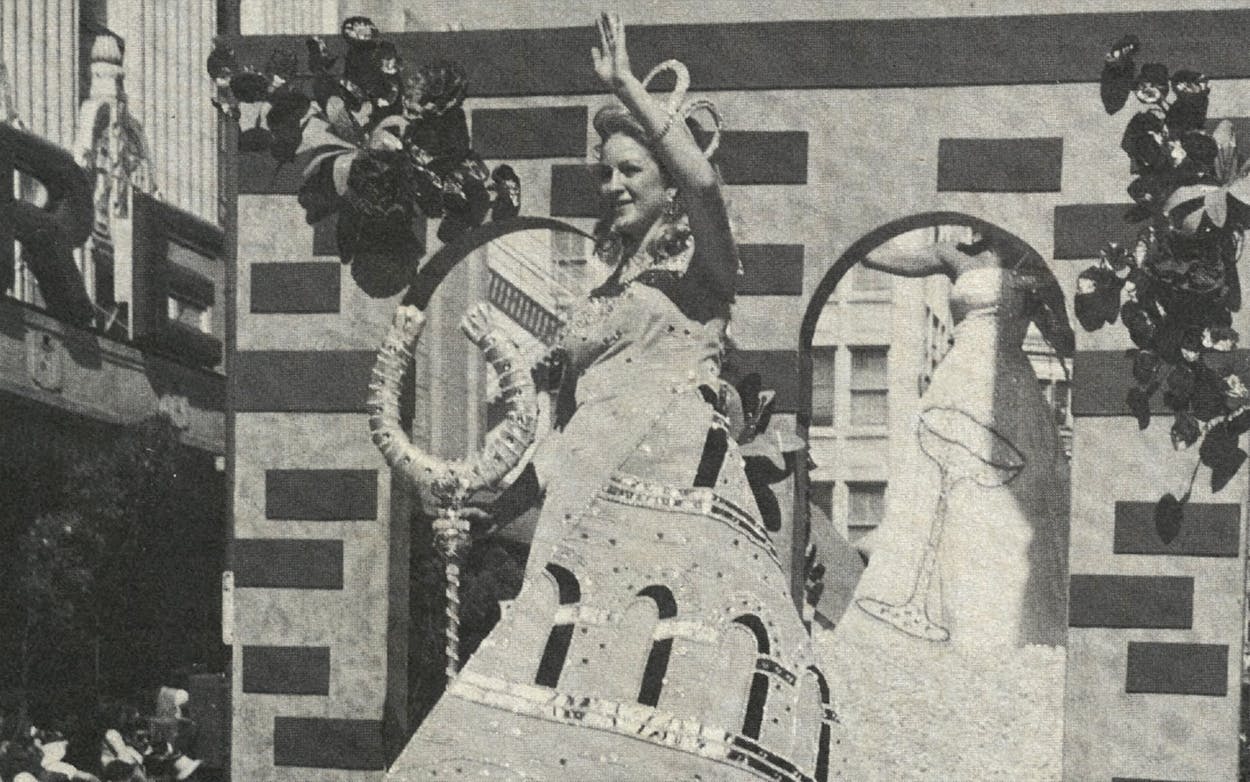

Fiesta pageantry starts on a Saturday evening, when the Texas Cavaliers, a group of businessmen done up in red-and-blue uniforms that would be the pride of any Balkan principality, gather in front of the Alamo for the coronation of King Antonio. Then on Monday night the king leads the river parade, where floats drift past 125,000 spectators crowding the river banks, the bridges, and the hotel balconies. On Wednesday night the patrician Order of the Alamo, in a show of pomp and ritual that would humble the Court of St. James’, crowns its queen and presents her court—princesses, duchesses, and “noble visitors to the court” who have collectively cornered the free-world market in velvet and rhinestones.

Friday morning the service organizations and church groups begin setting up folding chairs for the Battle of Flowers parade. The poor bring their own chairs and stake out viewing positions wherever they can. In due course the well-to-do fill the premium-price seats near the reviewing stand on Alamo Plaza, and later the windows and wrought-iron balconies of the Menger Hotel are filled with those of the local aristocracy who had the foresight to reserve rooms a year earlier. On the sidewalk in front of the Menger, disco hoots break out from the crowd when the drill teams in the vanguard of the parade pass in review, and on this one afternoon the ordinarily quiet Menger bar, where Teddy Roosevelt recruited his Rough Riders, again takes on a busy and exotic atmosphere.

In early afternoon the parade steps off, led by Fiesta officials and politicians in open cars. (In Alamo Plaza, there are cheers for Mayor Cockrell, boos for her Latino nemesis on the city council; a block away the responses are reversed.) There are the usual bands and drill teams, the Shriners on their motorcycles, the floats bearing the queens of colleges and military bases, and the royalty of the Order of the Alamo on the grandest floats of the parade.

Scarcely have the streets been cleaned and the chairs folded away when the church groups and service organizations return to set up the chairs again, this time for the torchlit Saturday-night parade, the Flambeau. At length, Miss Fiesta’s float passes, 325,000 spectators break for their cars, and Fiesta is—well, nearly over. There’s still a charreada (a Mexican-style rodeo) and a church fair to come.

Everybody has a great time, and the city’s businesses benefit to the tune of $20 million. Seen against this backdrop of universal gaiety, the carryings-on of carnival royalty might be taken for just more gaiety. That is the side of Fiesta seen by tourists and newcomers. But, over the years, this comic-opera royalty came to symbolize the Great Truth about Fiesta, as stated with something less than tact by a patrician San Antonian: “Fiesta is a private party to which everyone else is allowed to go after the fun is over.”

Fiesta began in 1891, when President Benjamin Harrison made an overnight stop in San Antonio. His visit coincided with San Jacinto Day, and the fashionable young ladies of the “metropolis of Texas” planned to honor both events with a parade. Heavy rains fell on the appointed day, and the President left town unparaded, but the ladies staged their show anyway on the following Friday. As the climax to the parade, the ladies drove their carriages back and forth in front of the Alamo and pelted one another with flowers. The fray lasted about half an hour, and the ladies had so much fun they decided to make the Battle of Flowers an annual event celebrating San Jacinto Day.

The society ladies long ago stopped throwing flowers at each other, but some quarters compensated by throwing barbs at them and at the other blue-blooded social clubs that ran Fiesta through World War II: the Texas Cavaliers, founded in 1926 to choose King Antonio from its own ranks, and the Order of the Alamo, founded in 1909 to choose the queen and her court from among its members’ daughters. Not surprisingly, it was the Order of the Alamo that aroused the bitterest resentment in the community.

The Coronation of the Queen of the Order of the Alamo is, for all practical purposes, the grand finale of the debutante season. Nine of last year’s twelve duchesses were also debutantes with the elite German Club, whose membership roll bears a striking similarity to that of the Order of the Alamo. The show is lavish beyond words. The duchesses’ robes, individually designed and hand sewn under the supervision of the Mistress of the Robes, cost upwards of $5000 apiece. One recent queen’s gown was especially grand—about sixteen grand, according to rumor. The stage setting for last year’s coronation, styled the Court of the Sun King, was a re-creation of the Hall of Mirrors at Versailles. Even the verbiage is splendid: for the coronation, young Kimble Brusenhan, UT coed, became “From the Looms of Lyon, for the Corridors of the King, Her Grace, Kimble Wright of the House of Brusenhan, Duchess of Woven Enchantment.”

However this may appear to the outsider, to the girls and their families the coronation is a hallowed tradition. The same family names appear repeatedly on the Order of the Alamo’s list of presidents (they are addressed as “His Eminence, the Cardinal”). Many of the current duchesses can trace their ancestry through three generations of Fiesta royalty. Last year Anne Harwood (“Depicting the Patchwork Fields of Franche-Comté, Her Grace, Anne Roane of the House of Harwood, Duchess of the Bountiful Harvest”), for example, followed in the slippers of her two sisters. She herself had been a page in the Court of Venice and in the Court of Classics. Two aunts, her mother, and her grandmothers were in previous coronations. Her mother was the head of the Battle of Flowers parade, and her father had been King Antonio L.

Family tradition can be an onerous obligation. It isn’t easy to put on a parade; the Cavaliers, some of whom must feel awfully silly in those uniforms, have a hectic schedule of appearances at schools and hospitals; for the girls, the coronation can be an ordeal of practicing deep court curtsies and smiling incessantly through an endless round of parties. Nonetheless, there was mounting criticism of Fiesta as just a society party.

Fiesta began to open up in 1947, when the San Antonio Conservation Society started A Night in Old San Antonio. In 1948 Reynolds Andricks, a wealthy businessman who was on the outs with the clannish Battle of Flowers ladies, organized the Flambeau to give merchants and lower-echelon service organizations a chance to have some fun. In recent years, the number of Fiesta events and participating organizations has grown dramatically. Today, although the gentry are still the stars of the show, they have to share a crowded bill with the likes of the San Antonio Bicycle Club, the Alamo Area Square and Round Dance Association, and the Chordsmen Chapter of the Society for the Preservation and Enjoyment of Barber Shop Quartet Singing in America.

But through the years the coronation remained virtually untouched, and resentment grew. The peasants didn’t object so much to the pretensions of those to the manner born as to the privacy of their sacred ritual. Although the ceremony took place in the cavernous Municipal Auditorium, the largest blocks of seats were closely held by the Order of the Alamo and its friends. Most tickets were expensive and the prevailing attire was formal.

Finally, last winter, Valhalla crumbled. The Municipal Auditorium, site of every coronation since 1926, was gutted by fire. The Order of the Alamo wanted to move the coronation to the Majestic Theatre, a magnificent old movie palace. The setting would have been ideal, but the Majestic’s paltry 2500 seats would have made the coronation even more private than before.

Joe B. Martinez, Jr., was not amused. Last year he became the first Mexican American president of the Fiesta San Antonio Commission, the umbrella group that coordinates and publicizes Fiesta activities. He wanted the coronation to move to HemisFair Arena, which can seat 16,000 for Spurs basketball games.

Now it was the order’s turn to be not amused. While the arena is a fine place to watch basketball and revival meetings, its spartan interior is not compatible with pomp and circumstance. But the Majestic’s inadequate stage and orchestra pit conspired against the order. For the coronation, the arena’s seating capacity will be cut to a relatively intimate 10,000, but even at that there will be a lot more two-dollar seats than in years past. If ticket sales hold up as expected, the ancien régime will be overwhelmed by hoi polloi.

The gentry will survive this latest indignity. If they’re losing their command of the public Fiesta, they still have their own private Fiesta to keep tradition alive: parties in private homes and at the country club; luncheons at the Argyle; formal balls at the hotels; casual gatherings at San Jose Mission and at the breweries. Even A Night in Old San Antonio opens a day early for the by-invitation-only King’s Merienda. With sufficient stamina, a proper young man or woman can make twenty private parties during Fiesta.

For the rest of the people, Fiesta is a lot more fun than it used to be. San Antonio’s diverse cultures and interests are on brilliant display. Populism came late to Fiesta, but it came with panache.

Oh, by the way, if you’re still wondering about Mayor Cockrell’s limousine being stuck in post-parade traffic, have no fear. When the king’s motorcade zipped past in its reserved lane, the mayor’s chauffeur, with a deft turn of the wheel, zipped right in behind it. The king didn’t mind. Noblesse oblige.

Mike Greenberg, a native of San Antonio, is a freelance writer now living in Dallas.

- More About:

- Texas History

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- San Antonio