Decades ago, when my dad and I were Texans exiled in Nashville, I would often see him tell people he was “fair to middlin’” after people would inquire about his general well-being. When asked what he meant, he’d explain, “Oh, it’s an old Texan expression to describe cotton. It means ‘doing pretty well.’”

But it always seemed to me he would use “fair to middlin’” when things were percolating along a little better than just “pretty well.” He would always have a twinkle in his eye when he said things were “fair to middlin’.”

Maybe it wasn’t my imagination. Back before the sale of steers and oil took over the Texas economy, Texas was the jewel in the crown of the cotton states, and much of our vernacular stemmed from the cotton patch, like “tough row to hoe.” (It’s “row,” a long procession of plants that need weeding, not “road”—nobody should try to hoe a road.)

While the saying originates in a British phrase, “fair to middlin’” unequivocally is a cotton patch term that took root in Texas. Thanks to progressive metal bands from northeast Texas and a Dwight Yoakam single, Texans tricked the Brits into accepting our own bastardized remaking— “fair to Midland” — as their own.

“Fair,” in this sense, means top-of-the-line, in the old British sense of “a maiden so fair” or Shakespeare’s “Happy the parents of so fair a child!” But as applied to cotton, the term is of relatively recent (at least post-Revolutionary War) vintage. Most of the cotton harvested and exported in the Southern states in the nineteenth century was trundled down to the coast and loaded up in ports like Galveston, New Orleans, Mobile, Charleston, and Savannah and sent to Liverpool, where it was distributed to “dark Satanic mills” across Lancashire, in northwestern England.

In Liverpool around 1800, the cotton brokers came up with the Liverpool Classification, a grading system for the raw material’s quality. The system was quoted in American newspapers up until the Civil War, acting as a nineteenth-century NASDAQ for Southern cotton farmers.

In 1828, per a Natchez, Mississippi newspaper, the Liverpool Classification ranged in quality from “ordinary and middling” to “middling to fair” to “fair to good fair” to “good and fine.” That highest grade denoted a supreme product that evidently was so rare, I could find no record of sale for such finely-wrought white gold in the accounts of several trading sessions.

While most of those adjectives stuck around in the vernacular, the Liverpool Classification was never widely embraced and had fallen out of favor by the time of the Civil War. By 1900, anarchy reigned — it seems like pretty much every American cotton buyer and seller had their own classifications for cotton, each dependent on how much or little they thought they could buy or sell it for. In real estate, realtors will tell you that some list prices are really “wish prices,” and that seems to be what was going on with cotton for several decades. Buyers downgraded the “fine” to “fair “and “middlin’,” and sellers upgraded the “ordinary” to middlin’, “fair,” and even “fine,” if they could get away with it.

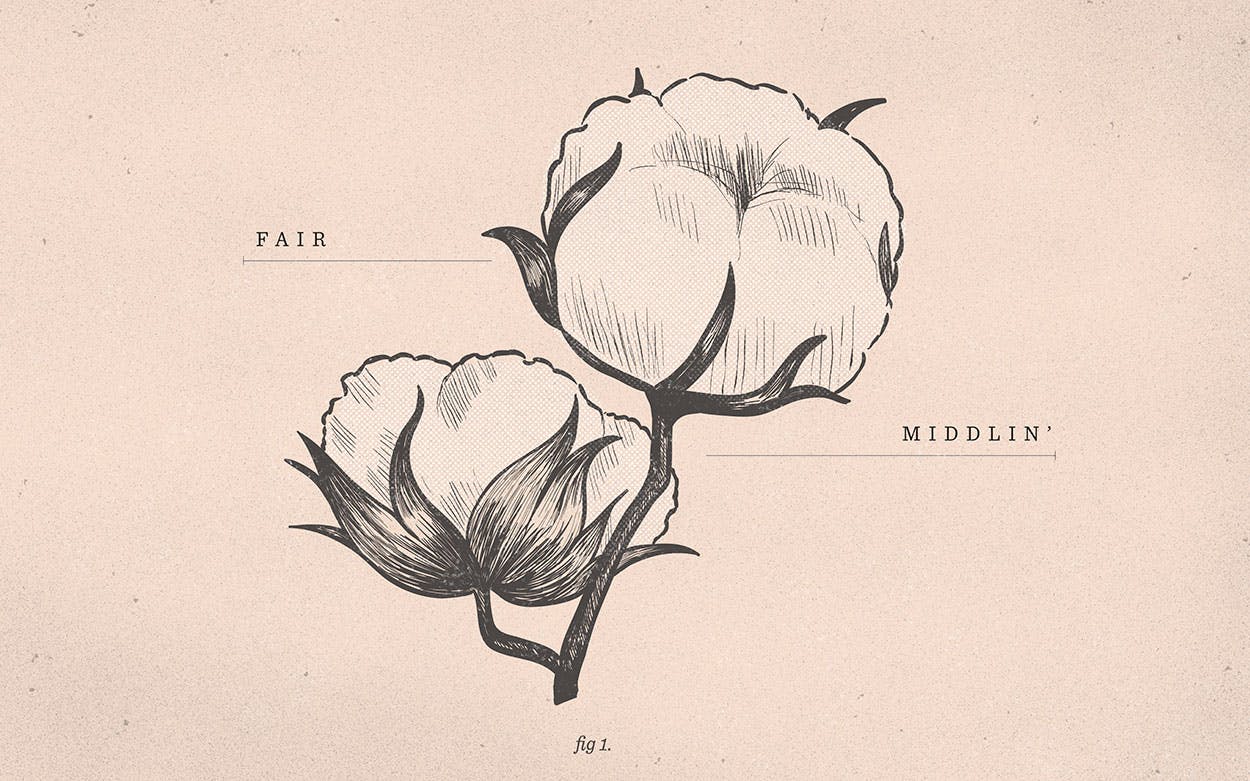

After decades of haggling on the markets, in 1909, the United States Congress took a stab at an American standard for cotton quality. After examining blind samples from all over America and overseas, and taking note of such qualities as its color (the whiter the better) and the amount of foreign impurities (everything from leaves, dirt, sand, and cut leaves to something called “pinhead trash”) the committee of experts came up with the following, from highest quality to lowest:

Middling Fair

Strict Good Middling

Good Middling

Strict Middling

Middling

Strict Low Middling

Strict Good Ordinary

Good Ordinary

Note that American egalitarianism — even the trashiest cotton was “good” (if merely “ordinary”) and the fanciest is only “middling fair,” rather than the Liverpudlian “good and fine.”

According to a 1951 advertisement for Paris, Texas’s Ayres’ department store, the congressional standard didn’t take. To celebrate “Cotton Week” at the downtown emporium, the store offered a chart alongside their economical cotton towels, boys’ blue jeans, and girls’ batiste slips. Among the 25 cotton standards, “fair” and “middling” make the top of the list.

And at some point — it’s hard to pinpoint when — people on both sides of the pond started switching “middling fair” to “fair to middling” (in the U.K.) and “fair to middlin’” in the South and Texas. It also vaulted out of the cottonfields and came to be used to describe many things — you could be feeling “fair to middlin” about life in general, or you could look out the window and see that the weather was much the same.

Somewhere along the way, the phrase lost its connotation for top-grade quality. Today, some see it akin to the more commonly American “can’t complain,” or perhaps the French “comme ci, comme ça.” For younger folks, perhaps it’s been replaced by “meh.” Despite my interpretation of my dad’s ebullient manner when saying it, that “so-so” connotation seems to be how it’s most often deployed today, even if, according to one word maven on the Internet, the distinction remained as late as the 1950s, when, on The Andy Griffith Show, a traveling salesman tells deputy Barney Fife that he is not “fair to middlin’,” but instead “middlin’, just middlin’.”

After making its way to Texas and losing some of its luster, the term evolved again, and we’ve since delivered it back to England in mangled form.

The “Fair to Midland” Variant

Oil replaced cotton as Texas’s lifeblood in the early 20th century, and like a mushroom after a downpour of black gold, the city of Midland popped up on the desiccated West Texas high plains. As cotton declined and oil ascended in importance, and because of the way we Texans talk, “middlin’” eased over into Midland.

The etymology is partially because of an old West Texas joke: some west Texans would tell you “it’s fair to Midland and partly cloudy to Odessa.” (Odessa being the gritty, smoky refinery town.) Others will joke that they are “fair to Midland” when approaching that west Texas oil hub.

An alternate spelling may be too cute to be true. In an East Texas preacher’s account in the Gilmer Mirror, a variant on this variant popped up in Houston in the early 1900s. According to the preacher’s story, an old lady boarded a bus and the driver asked her how she was doing. She replied, “I have the fare to Midland, so I’m doing okay.” (Being a long way from Houston, that would mean she was rich.)

In naming themselves, the northeast Texas band Fair to Midland intentionally played on Midland vs middlin’, while Dwight Yoakam’s “Fair to Midland” plays on both the city’s name and “fair,” just as in the anecdote of the lady on the Houston bus. (In Yoakam’s case, he is longing to get his “fare” to Midland, to reunite with the one who got away.)

“Fair to Midland” has even traveled all the way back to England, where, it seems that Brits have started to adopt it as their own.

The phrase started in Liverpool, in the very serious business of early 1800s cotton appraisal. The word “fair” came to denote more “average” than “very fine.” Then the standard devolved into argument in the U.S., and landed in Texas, where my dad picked it up from his parents, who in his dad’s case were just two generations removed from laboring in the Alabama and Mississippi cottonfields. My dad brandished it in Tennessee as a talisman of his Texas upbringing—at least, until a Nashville friend provided him with a better phrase: “Welp, I’m still north of dirt and drawin’ nourishment.” That’s all good and fine—which was what “fair to middlin’” always was meant to have meant anyway.

Read more in our Talk Like a Texan series here. And if you have a question about local parlance that you’d like explored, send us an email.

- More About:

- Texas History