Twelve shots boomed through the night sky in downtown Laredo. Residents, perhaps on an evening stroll or on their way to a movie theater, dispersed rapidly through the streets as the gunfire cracked. Some took shelter, while the brave and curious followed the sound. Those informal investigators found a group of men grappling on the sidewalk. One was Webb County deputy sheriff Will Stoner. Another was Manuel García Vigil, editor of the local Spanish-language paper El Progreso. Vigil had sustained three wounds—one through the arm, one through the right ear, and the third a graze to his scalp. The deputy emerged unscathed.

The following morning, on May 7, 1913, daylight illuminated the brick exteriors of the Laredo Weekly Times and the Stowers Furniture company buildings. Embedded in the masonry were lead bullets from the firefight.

Law enforcement officers in early Texas were tasked with not only settling the physical frontier, but also controlling the public narrative regarding their work. Then, as now, the official versions of events were challenged by local journalists. In episode three of our podcast White Hats, we explore how that dynamic played out among the Texas Rangers, local law officers, and Tejano news organizations.

Subscribe

Following the extension of railroad service to Laredo in 1881, the growth of the small border town skyrocketed: by 1900, the population of Webb County, where Laredo is located, had risen sharply to 22,000—up from 5,200 in 1880. Thousands flocked to the city in pursuit of jobs, many hoping to work on the railroad. Freight cars were packed with everything from cattle to onions. (In the early 1910s, Webb County shipped out 1,700 rail cars a year full of onions, mostly the sweet Bermuda variety, earning it the title of “Bermuda Capital of the World.”) The rail lines also brought visitors and new settlers, including Anglo Americans, who carried with them new cultures and different ideas of who should wield power and how. During that same period, brewing revolutionary unrest in Mexico led many Anglos to associate Mexicans and Mexican Americans with insurgency and violence, making them targets of attacks by some Anglo civilians as well as law enforcement officers. At the turn of the century, Laredo was home to eleven Spanish-language publications, many of which reported on injustices inflicted upon Mexican Americans. Two newspapers stood out: Vigil’s El Progreso and La Crónica, published by Nicasio Idár. Both papers often published editorials condemning racial abuse and criticizing national politics, such as U.S. involvement in the Mexican Revolution.

A 1913 El Progreso editorial critical of Webb County sheriff Amador Sanchez led to violence on Laredo streets. About a week before Vigil was shot, Sanchez wrote a letter to El Progreso demanding to know the editorial’s author. “I beg you to tell me,” he wrote, “who they are, the persons that make themselves responsible of so many gratuitous insults that I have been the object of.”

The situation escalated when, days later, Vigil and some friends visited a local saloon. Sanchez, Deputy Stoner, and two of their friends walked in. According to court records, Sanchez and Stoner went into an adjoining room to speak and later followed Vigil’s party outside. Amid a scuffle, Stoner struck Vigil with a pistol, and the shooting followed.

Stoner unsuccessfully argued self-defense. He was convicted of aggravated assault, fined $100 (equivalent to about $3,000 today), and sentenced to three months in county jail. Shortly after his release, he returned to working in law enforcement. Sanchez, who stepped down as sheriff in November of 1914, remained a prominent public figure.

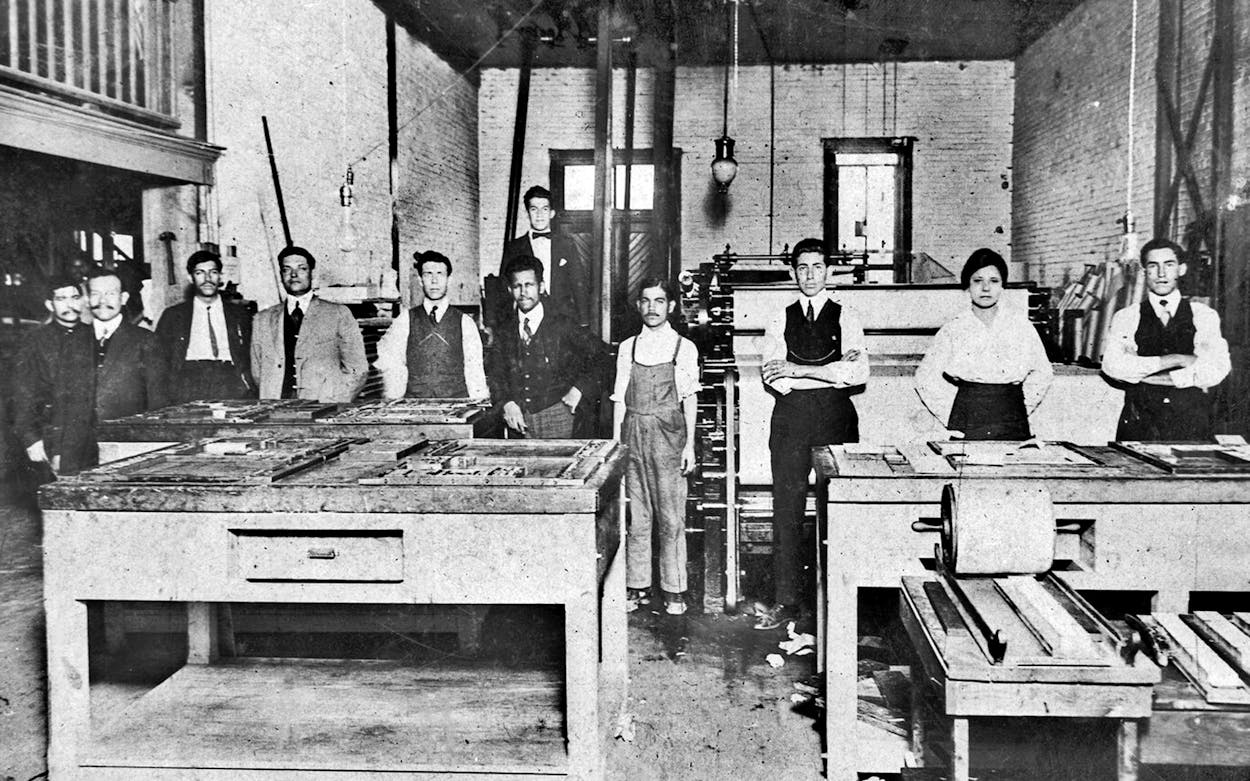

The year after his assault, Vigil again came in conflict with law enforcement—this time, with a unit of the Texas Rangers. This clash began over an editorial some believe was written by Jovita Idár, eldest daughter of the publisher of another local Spanish-language paper, La Crónica, who was also writing for Vigil at El Progreso. (While the Texas State Historical Association maintains Idár was the editorial’s author, other research, such as that of Chicana historian Gabriela González, attributes the writing to Vigil.) In the spring of 1914, El Progreso, which had been critical of U.S. involvement in the Mexican Revolution, published a scathing editorial about President Woodrow Wilson’s military intervention in Veracruz. The editorial enraged state leaders, and Texas Rangers sought to confront the author. According to Jovita’s brother, Aquilino, when the Rangers arrived at El Progreso’s office, his sister defiantly blocked the building’s entrance and they retreated. But around 5 a.m. the next day, the Rangers broke into the newspaper’s office and destroyed nearly everything inside, including the printing press.

The paper shut down, and, according to Aquilino Idár’s account, Vigil eventually returned to Mexico. Jovita returned to La Crónica and, after her father’s death in 1914, became its editor. In 1916 she founded the paper Evolución, which continued to advocate for the rights of Mexican Americans.

Today, in this city where Mexican American journalists put their lives on the line, stands Jovita Idár’s El Progreso Park, which was renamed in her honor in 2020.

- More About:

- Texas History

- Laredo