This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Three Apollo astronauts were circling the moon and millions of Americans were sticking close to their televisions on a day in May 1969 when an astral event of a different order took place in the Panhandle town of Plainview. Two thousand citizens turned off their TV sets and headed for the Hale County airport to welcome a star. Jimmy Dean, local boy made good, was coming home.

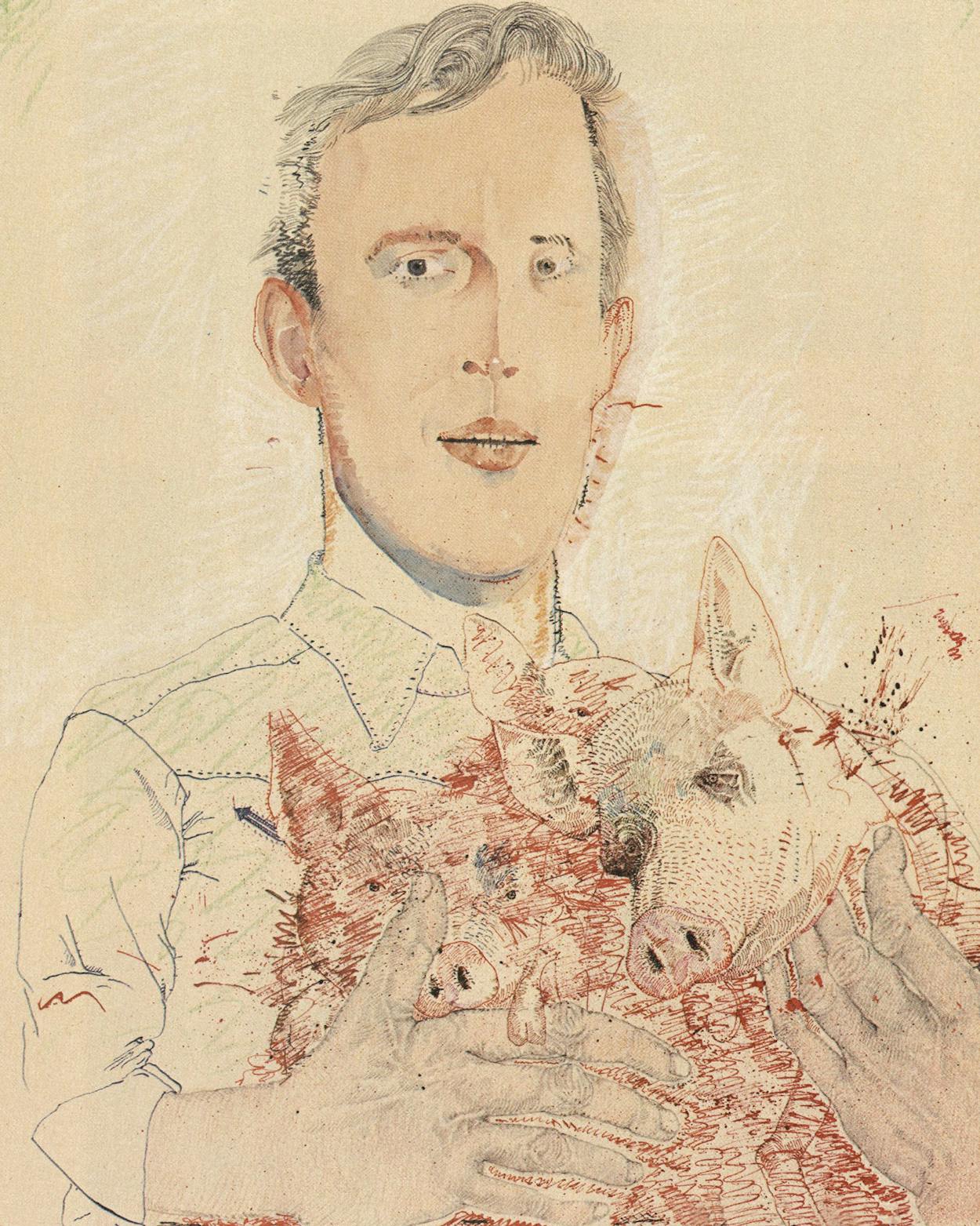

To the rest of the country, Jimmy was known primarily as the country and western singer who had recorded “Big Bad John” and appeared frequently on television, usually to sing but more recently to pitch a product called Jimmy Dean Pure Pork Sausage. In Plainview, however, he was nothing short of a hero in those days. The occasion of the gathering at the airport, headed up by Governor Preston Smith of nearby Lubbock, was the formal opening of Dean’s new sausage factory, just north of town. The sausage company was strictly a local operation (Jimmy’s two principal partners—his younger brother, Don, and his cousin’s husband, Troy Pritchard—both lived in Plainview), and it was the biggest thing to hit the Panhandle since irrigation.

Eventually the factory employed 150 people and had an annual payroll of more than $3 million—sizable figures for a farming town of 18,000 in a time of depressed agricultural prices and dwindling underground water. It started a hog boom in the Panhandle, an area previously devoted mainly to cotton and cattle. Because of Jimmy’s sausage, Plainview would proclaim itself “Home of Jimmy Dean” in big black letters on the water tower near his plant, and pigskin coats—marketed by the Dean operation as by-products of the sausage making—became the fashion in town. Jimmy Dean Pure Pork Sausage was an instant success, thanks largely to Jimmy’s television pitches. You remember the spots, no doubt. He performed them ad lib, sitting on a stool against a plain backdrop, talking in soft, comfortable rhythms about how his sausage was made “from the whole hawg, not jus’ the leavin’s.” The little chats had the ring of down-home truth in a time of perplexity, and his ads went over better than anyone had dreamed. And his sausage in those days really was different. It was made from top hogs, younger and leaner than the sows used by the rest of the industry. It was packaged warm rather than chilled, the way most other companies did theirs. Moreover, it created its own market: people who had been suspicious of fresh pork sausage began eating it for breakfast. Within six months the firm was in the black.

But all that was long ago. Now the tan metal building that once turned 1500 hogs a day into sausage is idle. Inside, where a watchman makes his rounds, a million dollars’ worth of machinery gathers dust. Except for an abortive reopening in 1979, the factory has been closed for five years. You can still buy Jimmy Dean sausage—hot, mild, and sage flavored—in markets from Berkeley to Boston, but it’s made from sows these days, not top hogs. The factory is in Iowa and so are the pigs; most Panhandle producers gave up raising them years ago. The Jimmy Dean Meat Company itself is run from offices on the eleventh floor of a glass tower on Mockingbird Lane in Dallas. Of the three original partners, only Jimmy remains; the others left amid accusations, recriminations, and litigation. Five years ago Don sued Jimmy for libel and slander. Back in Plainview, you rarely see pigskin coats anymore.

Today Jimmy Dean at 55 is lean and fit, though a few creases mark his tanned face. He is still president of the company, but his home is in New Jersey and he spends a lot of his time on his 61-foot yacht, Big Bad John IV, out of Fort Lauderdale, leaving the day-to-day running of the company to full-time executives. Characteristically upbeat, he says that the firm is in fine shape and he expects great things for a company-owned chain of restaurants that will bear his name; the first three have already opened, all in Columbus, Ohio, and a fourth is planned for Oklahoma City. But it hurt him that his West Texas plant closed. Like many a poor boy who left home and hit it big, Jimmy wanted to do something for his hometown. But along the way the strains of business, clashing egos, and a bitter family feud knocked his plans off course. Last year Plainview repainted the big water tower that you can see from Interstate 27 as it loops toward Amarillo. Now only silver paint glistens where Jimmy Dean’s name once stood.

“Because of Jimmy’s sausage, a hog boom started in the Panhandle, Plainview proclaimed itself ‘Home of Jimmy Dean’ in black letters on a water tower, and pigskin coats became the fashion in town.”

Towns usually grow into the wind. In the Texas Panhandle, that means toward the west and northwest. Back around the turn of the century the first wealthy citizens built their stately brick homes just west of downtown Plainview, and since that time several generations of expensive new houses have led a slow march in the direction of the fresh breeze. Jimmy Dean grew up on the other side of town—downwind, where you can often smell the city dump or the slaughterhouses. Aging frame houses with peeling paint cluster in the shadows of grain elevators and cotton gins, behind the railroad yards, next door to auto wreckers or feed mills. Here, on the East Side, are mobile homes, the barrio, the black neighborhoods, the public housing projects. An occasional larger home with fresh paint and a tidy yard bears witness to the owner’s reluctance, despite some newfound prosperity, to leave familiar ground.

Jimmy Dean’s mother, Ruth, was like that. Back in the early sixties, when “Big Bad John” left Jimmy flusher than he’d ever been, he wanted to build her a new house. But Ruth Dean, a simple, unpretentious soul and a loyal member of the neighborhood Baptist church, didn’t want to leave the unincorporated area known as Seth Ward, where the family had settled in the depths of the Depression thirty years earlier. Jimmy had to be content with building her a new brick home right on the site of the old white frame house.

His childhood poverty is a theme that pops up repeatedly in his conversation, his music, and even his TV appearances. He used to talk about how he grew up among the boll patches. One of his biggest hits, “I.O.U.,” was a paean to his mother. When I spoke with him during one of his brief visits to his Dallas headquarters, an airy, spacious corner office with two bear rugs on the floor, the conversation quickly turned to his childhood and his mother. I mentioned the first time I had seen him—25 years ago, when he addressed an assembly at Plainview High School during my sophomore year. “When I was a kid, they laughed at our clothes and they laughed at our house,” he told me, “but when I walked out on that stage and they gave me a standing ovation, I looked out at that lady in the audience and saw all that hurt repaid. It was the most rewarding appearance I ever made in show business.”

Growing up, Jimmy did whatever he could for money—pick cotton, drive combines, clean chicken houses and septic tanks. His father was a preacher, a singer, and an inventor whose pet project was an irrigation pump designed along the lines of a perpetual motion machine. G. O. Dean left his family in 1939, when Jimmy was eleven and Don nine. Ruth Dean made ends meet by cutting men’s and boys’ hair in one of the small rooms of her house. Jimmy was just another kid from the wrong side of the Santa Fe Railroad tracks.

One day in 1944, a year short of his high school graduation, sixteen-year-old Jimmy Ray Dean hopped a Greyhound bus for Dallas and enlisted in the manpower-starved Merchant Marine. After he made one voyage to South America, the war ended, and he returned to Plainview to work for an irrigation equipment company. When he left again in 1946 to join the Air Force, Jimmy was gone for good.

He drifted into singing and wisecracking in seedy nightclubs while he was stationed near Washington, D.C. He was never a musical virtuoso, but he had a pleasant voice and knew how to tell a good story. Once he was out of the Air Force, Dean began to appear on an Arlington, Virginia, radio show, then on local television. In 1958 he graduated to his own daytime variety slot on CBS. He was by then a local hero back in Plainview, but true stardom eluded him.

In 1961 the unexpected success of “Big Bad John,” which Jimmy wrote as a last-minute filler for a Nashville recording session, changed his life. The countrified talking blues about a heroic coal miner, told in rhythms and accents reminiscent of Tennessee Ernie Ford’s “Sixteen Tons,” became an international hit and sold five million copies. Jimmy appeared on British television and at Las Vegas casinos, and he headlined a weekly prime-time variety program on ABC from 1963 to 1966. When Johnny Carson was away or between contracts, Jimmy often served as host on the Tonight show, where his laid-back country wit stood up surprisingly well. With the money, Jimmy bought himself a 35-foot yacht, the first Big Bad John, and a ranch in Virginia that he jokingly called Weedville; he built his mother’s new house; and he invested in Troy Pritchard’s hog farm, the operation that led to the sausage enterprise.

He usually sings other people’s music. Of his own compositions, most are “talking” songs like “Big Bad John,” “Dear Ivan,” and his tribute to his mother, “I.O.U.,” written (and delivered on TV) in 1959 but not recorded until 1976. Mitch Miller, his recording executive, had the option to record it when Jimmy first came up with the piece, but Miller rejected it as “too corny.” (Sample lyric: “You had the eye of an eagle, the roar of a lion, but you always had a heart as big as a house.”) Ruth Dean is said to have been a bit embarrassed by the fuss and to have agreed privately with Miller’s judgment. But “I.O.U.” sold a million 45’s in two weeks.

“Like many a poor boy who left home and hit it big, Jimmy wanted to do something for his hometown. But the strains of business, clashing egos, and a bitter family feud knocked his plans off course.”

Jimmy has always been conservative in his choice of music—simple country tunes, ballads, and gospel-tinged hymns. He never showed any kinship with West Texas’ other famous musical progeny, Buddy Holly and Waylon Jennings. He resisted rock’s first and second waves in the fifties and sixties, and even in the seventies, when Nashville itself yielded to the popularity of the hard-edged progressive country sound of Waylon and Willie Nelson, Jimmy didn’t change. Perhaps that had something to do with the decline in his show business career. By the mid-seventies Nevada casinos were offering him fewer dates. “Jimmy’s image had a shelf-life problem,” a former sausage executive told me.

In fact, the sausage ads on television may have done as much to prolong Jimmy’s entertainment career as they did to launch his meat product. Now he appears at state fairs and rodeos and makes promotional tours for the sausage company. (“State fairs are very big business. They make Vegas look like Sharecroppers’ Row,” he said in an interview several years ago.)

The audience for his commercials has changed too: he’s on radio more than TV these days. In a recent series of spots in Dallas, he delivers miniature versions of his talking songs, with plain little rhymes against the background of a solo guitar. He pitches politics more than pork, concentrating his wit on society’s foibles. He finds fault with airlines, the postal service, welfare chiselers, taxes, federal deficits, gasoline prices, lawyers, doctors, auto mechanics, weathermen, and imported cars. Here’s Jimmy on the U.S. mail: Funny thing that letter I mailed/Somewhere the postal service failed/So I think about it and it makes me sore/The service gets worse and the stamps cost more/Ain’t that a mess?/I’ll take Pony Express. At the end the listener learns that the song was brought to him by Jimmy Dean Pork Sausage, and that’s the extent of the sell. The ads have proved so popular in Dallas that people have once again taken to stopping Jimmy for autographs whenever he happens to be in town.

The whole hog thing began in Plainview on Christmas Eve, 1965, after Jimmy had flown in from the East Coast to join a big family celebration at the new home he had built for his mother. Jimmy talked to Troy Pritchard—a local farmer who had married a Dean cousin in 1951—and became interested in the hog farm Pritchard and his brother owned. So on Christmas Day Pritchard drove his famous relative out to the place. Pork prices were down, the operation was losing money, and cosmetic problems, like peeling paint, were being neglected, but the Pritchards still insisted on strict sanitary procedures. Not only were the pigs prevented from engaging in the time-honored porcine practice of wallowing in the mud, but their cloven hooves never even touched the ground. From infancy the pigs were raised on elevated floors of wooden slats. Every night the decks were rinsed clean and disinfected. Like all visitors, Jimmy had to wear special clothing and overshoes to protect the animals from bacterial contamination.

Pritchard was surprised when Jimmy wanted to buy into the farm, which was running in the red. “Well,” Troy recalls Jimmy saying, “back in Nashville Ray Price is always talkin’ about his racehorses, and Eddy Arnold has his prize cattle. When I go back there to record, I think it’d be a hell of a deal if I could talk about my hogs. ’Course, I’d like to make some money if I could, but that’s not the main thing.”

So before Jimmy flew back to the bright lights, he bought Troy’s brother’s half of the future Jimmy Dean Pig Parlor. Troy stayed on as equal partner and manager. Jimmy told Troy that his New York lawyers saw it as a tax write-off, but to Jimmy himself it was much more. He pumped money into it, saw it double in size, and showed it off to some show business luminaries. When pork prices improved, the Pig Parlor even began to show a modest profit. Then, still discontented with the prices they were getting for their swine, Troy and Jimmy decided to make sausage out of their hogs and market it in the Southwest.

The next partner to join was Jimmy’s younger brother, Don, who had advanced from delivering milk to running the local Borden distributorship. Each partner held a third of the stock in the J-D-T (Jimmy, Don, Troy) Products Corporation—actually a bit less than a third, since they cut a real meat-packer in for 6 per cent of the action. This junior partner was Ken Brown, an experienced plant manager for a slaughterhouse in Lubbock. Brown designed the 17,500-square-foot plant, oversaw its construction, and ran it once it opened. Don Dean set up the initial marketing network. Troy Pritchard handled the negotiations with bankers in Plainview and Dallas and with the federal Small Business Administration for a $320,000 loan to build the plant.

By the time sausage operations began in the spring of 1969, J-D-T was part of a mini-conglomerate—the Pig Parlor, a feed mill, a plant to process pig hides and ship them to Mexico (where they were made into coats and jackets and, in many cases, resold to West Texans), and SwineTech, a company to market a hog skinner that Ken Brown had developed. It’s really just a glorified winch, but until Brown invented it, nobody had yanked whole pig hides on an industrial basis. Most were thrown away. Now Brown’s hog skinner is used in factories all over the world.

Not only was the sausage plant the first to use the hog skinner, it was also one of the first large operations to bone, grind, and package pork while it was still warm instead of chilling it first. A pig became packaged sausage in little more than an hour. The sausage was then quick-chilled to 40 degrees before being shipped out in refrigerated trucks. Organs and other spare parts were used for cat food.

“By the midseventies the Iowa plant had long since assumed first place in production over Plainview, and the original West Texas operation was becoming more and more a stepchild. In March 1978 it was shut down.”

Some people couldn’t stand the blood, but most of the employees reckoned it was the best job in town, whether they were on piecework or hourly pay 50 cents to $1 above the minimum wage. The workers had a profit-sharing plan, bonuses for increasing production, and plenty of overtime if they wanted it. Morale was high, and production records toppled time and again. Once, when the plant turned out more than a million pounds of sausage in a week, Jimmy flew in food and champagne for everyone. “It was like one big family in the early days,” a woman who had worked at the plant from the day it opened in 1969 told me. “Jimmy would put on a hard hat and a white coat and wade through the blood and guts, patting the guys on the back, telling them what a good job they were doing. I was one of his pets. He always kissed me on the cheek, and I’d come home and tell my husband I couldn’t wash my face.”

Then things started to go wrong. The partners in the fast-growing firm fell to bickering among themselves. For one thing, Jimmy Dean had a hot temper. Once he fired Ken Brown over the telephone, and Troy Pritchard had to fly to Burbank to persuade Jimmy to change his mind. Brown was the only person who knew the meat-packing end of the business, and his loss would have been a blow to the young enterprise. When Pritchard leased a Cessna, Ken Brown complained that he used it too much. There were so many first-class airplane rides that the company finally had to issue a formal memorandum about it. Don Dean was, by all accounts, a great first-meeting salesman (“Hi, I’m Jimmy Dean’s brother, and I’d like to sell you our sausage!”), but some distributors complained about him to Pritchard, who recalls, “after a point, Don became Mr. Dean.” He had to fly to Memphis once to mediate between Don and a distributor.

Even though sales were booming, the company was chronically short of cash, partly because of its unsophisticated accounting, partly because of its generous spoilage allowances to distributors, but most of all because the business was expanding too fast without enough capital. The partners often didn’t have enough cash to meet current expenses and cover the four-to-six-week lag between buying hogs and getting paid for the sausage. Pritchard remembers once borrowing $200,000 from his family to meet payrolls. The company resorted to short-term borrowing at interest rates up to 16 per cent—in an era when prime was 6 or 7 per cent—which simply handed over a chunk of its profits to Chicago financiers.

Meanwhile, the partners, relying on overoptimistic sales projections, had committed the firm to nationwide growth by investing in a bigger and more modern meat-packing plant in Osceola, Iowa. The Midwestern community had pushed hard for the second factory, donating land for the site and promising immediate water and sewer services. And Osceola was in the heart of swine country, while West Texas hog raisers could not increase their production fast enough to keep up with the Dean company’s demand. Not long after the Iowa plant opened in 1972, however, sales leveled off and the company could not run both plants at capacity. Years later a former company executive said, “With hindsight, we should simply have expanded the Plainview plant.”

With the company in need of new capital, the obvious answer was to go public. In the winter of 1971–72 Troy Pritchard flew to New York every week or two to meet with Jimmy Dean’s attorneys and representatives of the underwriting firm of F. Eberstadt. The plan was to sell Jimmy Dean Meat stock over the counter, but just when it was about to happen, the personality clashes erupted again.

One day early in 1972 Pritchard, Don Dean, Jimmy Dean’s attorneys, and representatives of the underwriting firm gathered around a big conference table overlooking Lower Manhattan and the Hudson. The underwriters, optimistic about the firm’s potential, proposed to offer the public a quarter of the company’s stock for $12 million. If the stock maintained or improved its value, each of the three major partners would be holding shares worth that much or more, and even Brown’s 6 per cent would be worth plenty. “We were all sittin’ there with big eyes,” recalls Pritchard. “That was one sweet deal.”

But when the underwriters suggested switching corporate titles around to reflect more accurately the real functions of the present officers, they ran afoul of family pride. Jimmy Dean, the underwriters suggested, should become chairman of the board, a traditional position for a largely absentee major stockholder. Brown and Don Dean should both be vice presidents (for production and sales, respectively), and since Troy Pritchard was most familiar with all aspects of the business, he should become president.

As Pritchard remembers it, Don Dean was livid. “He stood up and said, ‘By God, my name is Dean, and if anybody’s going to be president of this corporation besides my brother, it’ll be me!’ ” The meeting stopped in its tracks. In a hurried private conference in another room, Pritchard tried in vain to change Don’s mind.

“I begged him,” says Troy. “I said, ‘Don, we’re talking big money—more than we’ve ever dreamed of. After it’s over, call me the janitor if you want to. But let’s put this deal through.’ ” But Don refused. He accused Pritchard of trying to steal the firm from the Dean brothers, in spite of the participation of Jimmy’s lawyers in the negotiations. The meeting was over.

The collapse of the New York meeting was the pivotal moment in the breakup of the original partnership. Pritchard flew to Nevada to see Jimmy, as he had done so often in the past. Once, Jimmy had met him at the Reno airport in one of casino mogul Bill Harrah’s prize cars, a gold Rolls-Royce limousine. Wearing a chauffeur’s cap, Jimmy had driven it right up to the ramp of the plane. But this time was different; Don had already called. Jimmy sided with his brother, echoing Don’s accusations: Pritchard had conspired to take the company away from Jimmy and Don by getting himself named president. Even Jimmy’s attorneys, summoned to Las Vegas from New York, couldn’t defuse the situation; in the heat of argument, he fired them on the spot. He later rehired them, but Pritchard was not so fortunate. Troy took a long vacation, then decided that June to sell out.

Ken Brown, the only professional meat-packer in the firm’s top levels, was the next to leave. He thought about quitting with Pritchard in 1972 but felt obliged to finish building the Iowa plant, at that time a half-million-dollar hole in the ground. But he made himself a nuisance by continuing to urge that the company go public—the only way his 6 per cent share would ever amount to much. The company made some more moves in that direction, but it never did go public. In 1975 Brown was fired, and he sold his stock back to the company, retaining only the foreign patent rights to his hog skinner.

For the first time the meat company was strictly a brother act. Jimmy had relinquished the title of president to Don. Each held 50 per cent of the stock, and there were only four members of the board of directors. The stage was set for a classic standoff if the new arrangement didn’t work out. And it didn’t.

The company Don took over was a very different creature operating in very different times from the one the four partners had started just a few years before. Pork prices rose sharply, and with them the firm’s costs. Raising capital by offering stock was out of the question. The stock market was in the doldrums and the $500,000 the company had spent preparing to go public was down the drain. The economy was wallowing in the mid-seventies recession, which had cut into the purchasing power of blue-collar families, the chief consumers of breakfast sausage. Though Dean’s product was distributed in 46 of the 48 contiguous states, its profits had almost disappeared. And it was becoming clear that the company had over-expanded. After reaching a high of 23 per cent of the fresh pork sausage market in some areas, Jimmy Dean sausage fell off toward a level it has generally maintained since then—it currently claims 15 per cent of the national retail market, or 60 million pounds of sausage a year. That was a healthy enough slice to transform a small West Texas family enterprise into a sizable corporation, but it was far below the optimistic projections that had led the firm to build a second plant in Iowa and lease a third, to produce smoked sausage, in Mississippi.

Faced with mounting problems, Don Dean called in an experienced food executive, Al Holton of the feed company Central Soya, who came aboard in 1974 and ended up running the company as executive vice president. “When I arrived, the company had essentially failed,” recalls Holton. In fiscal year 1974 the Dean company showed its first operating loss. Holton and Don Dean’s strategy was to borrow heavily from Dallas banks and to cut operating expenses. Cutting costs took some doing. Jimmy was unhappy about Holton’s cuts in the advertising budget—and not just from pride. Jimmy and Don were stockholders in a new Little Rock publicity firm, Holland and Associates, that handled the sausage company’s multimillion-dollar advertising account, and for several years they had enjoyed the dividends and expense accounts that the arrangement had furnished them. But the really hard part was getting Jimmy to go along with the decisions that didn’t sit well back home in Plainview. Hometown feelings had already been bruised when the corporate headquarters moved to Dallas in 1974. It made sense—the firm’s accountants were in Dallas and so was its major long-term lender, and besides, to get from one factory to another the executives were always flying through Dallas anyway—but those left behind predictably weren’t sold on the wisdom of the move. (“Every time some local firm moves to Dallas,” a Plainview attorney told me, “they get taken over by big-city boys.”)

“When Ruth Dean died in February 1982, Jimmy and Don came to the funeral with their wives and children, and they put a good face on things. But they didn’t sit together.”

At Holton’s direction, and to Jimmy’s dismay, the Plainview plant stopped paying Omaha top prices for locally raised hogs. Farmers accused the company of violating verbal contracts; one farmer told me that he remembered a company spokesman saying that the agreements wouldn’t stand up in court. Regional farmers had responded to the Dean company’s appeals and promotions by tripling hog production, from 200,000 in 1965 to 600,000 in 1972. Now many farmers, enraged, looked for other markets or gave up raising pigs altogether. But the real shock came when the company wanted to buy sows instead of top hogs. Sows that had outlived their usefulness as breeders were, and are, the common stuff of American sausage (unsuitable for choice cuts, they are older, bigger, and cheaper than six-month-old top hogs), and henceforth the Dean company, like its competitors, would make its sausage from sows. Sufficient numbers could be found only in the Midwest, where virtually every farmer raises hogs on the side, so the Plainview plant began to import them. West Texas farmers were cut off from their major market for top hogs. Many felt betrayed. By 1980 regional hog production had returned to 1965 levels, but Holton maintains that the switch to sows saved the company.

Jimmy now defends sow sausage. He says it is leaner (a debatable point) and redder and better-quality sausage than any his company has ever made. At the time, though, he resisted the switch to sows. On the few previous occasions when he had discovered a couple of sows among the hogs waiting to be slaughtered in Plainview, he had raised the roof. “We always took a few sows if the farmers wanted to unload them,” Ken Brown says, “but we didn’t dare tell Jimmy.”

By the mid-seventies the Iowa plant had long since assumed first place, and the original West Texas operation was becoming more and more a stepchild. Forty employees were laid off; they picketed the Plainview plant. In March 1978, following the company’s worst year ever, the operation in Plainview was shut down. The firm then spent $1.5 million reequipping the West Texas plant for a butchering and meat-packing operation designed to provide regional farmers with a market for their top hogs, but it never took off, because once-burned farmers wouldn’t deal with the company anymore. Jimmy made a personal appearance in town to promise to buy all the hogs the area could produce, but even that didn’t help. “We needed seven thousand hogs a week, but we were only getting two thousand,” says a former company executive. Once again, the Plainview plant had to import swine. The operation lost money, and the plant closed for good in January 1980. Jimmy told me that the company has new plans for the installation, but he declined to be specific, saying he didn’t want to tip off competitors.

Meanwhile, a new power struggle had developed, this one between Jimmy and Don. By early 1977 Don and his right-hand man, Holton, had been in charge for two years. They felt they were in the process of turning the company around, but the balance sheets showed the firm was still in trouble. Jimmy learned that the firm had reimbursed Holton for losses in the commodities market, and he began to feel that the operation was being mismanaged. He was also distressed that the company had earlier changed from one-pound to twelve-ounce packages, which he called cheating and “trying to bamboozle the American housewife.” Jimmy and Don began to discuss who should buy out whom. Then, Jimmy even tried to fire Holton, but he didn’t have the power. Some of the executives in the office sided with Jimmy; others were so annoyed by his involvement that they filed suit and persuaded a Dallas judge to restrain Jimmy Dean from interfering in the company’s day-to-day operations. Jimmy, who still held 50 per cent of the stock and was chairman of the board, boycotted the 1977 board of directors meetings, though he was in Dallas at the time. As part of the settlement of the dispute, Don agreed to turn the company over to Jimmy. After tense and complex negotiations, Don sold out—the third partner to do so in five years. Afterward, the officers and employees of the corporation discussed buying Jimmy out while retaining him on the board and as chief publicist, but Jimmy wasn’t interested.

The company’s problems did not end with Jimmy’s takeover. The cash crunch persisted; in late 1977 five corporate officers bought $156,000 worth of stock from the company so that Jimmy Dean Meat could pay the bills. Many of the executives Jimmy had inherited left the company. After 1978 the firm reinstituted Jimmy’s cherished one-pound packages and increased production. Today the firm turns out roughly a million pounds of sausage a week—just about the peak output of the old Plainview plant.

Now Don lives with his wife and children in Irving, manages a few investments, and plays a lot of golf at Las Colinas Country Club. The $2.5 million settlement with the sausage company assured his children’s financial future. Most of it was in the form of interest-bearing notes and titles to the Dean pig farms and feed mill in West Texas. Holton, who has returned to a managerial position with Central Soya in North Carolina, still expresses fondness for the Jimmy Dean “I know the best and love”—but not for the Jimmy Dean who accused him in court of “theft of corporate property.” Don, under a gag order imposed by Dallas federal judge Barefoot Sanders after the Dean brothers ended up in court, is thoroughly sick of the affair and doesn’t talk about Jimmy at all.

As Don’s legal complaint tells it, after the buy-out, in the winter of 1977–78, Jimmy Dean began to bad-mouth his brother to the press. He called the company’s switch to the twelve-ounce package a rip-off. On television he read a nasty poem about Don on the nationally syndicated Mike Douglas Show:

Never go into business with kinfolks

An old saying you’ll find to be true

’Cause if you go into business with kinfolks

They’ll soon give the business to you.

When you make your brother a partner

You start ills for which there are no cures.

You’ll find he’ll develop eye trouble

And he can’t tell his money from yours.

Don slapped his brother with a $4.3 million libel and slander suit in federal district court in Dallas. At a hearing before Judge Sanders, neither Dean acknowledged the other’s presence. The brothers settled out of court in February 1980, but Sanders’ gag order, which is unusually sweeping for a civil case, remains in effect. Neither Dean can discuss the other or the other’s past role in the sausage business, in public or in private, nor can they discuss the terms of their settlement. Jimmy, an outspoken man, is accustomed to good relations with the press, and it goes against his grain to comply with the order. Indeed, some vague references to his differences with Don that appeared in the Dallas Morning News last December drew a quick legal protest from Don’s lawyer.

The family cold war extended all the way back to Plainview. Ruth Dean suffered a stroke in 1978 and was moved to a nursing home. Jimmy hired a Plainview lawyer to seek a court order restraining Don from entering their mother’s home. (He didn’t get it.) Then in early 1980 Jimmy had some local Dean company employees sell the contents of Ruth’s home at a garage sale—without telling Don. Don later placed an ad in the local paper: “To all buyers of household items sold at public sale March 14 and 15th, 1980, at 801 E. 24th Street (property of Mrs. Ruth Dean). Family members who were unaware of the sale, and Mrs. Dean, want to recover as many of the items as possible. Interested parties are asked to call Don Dean.”

When Ruth died in February 1982, so many people were expected at her funeral, mainly because Jimmy would be there, that the services were held not in her old church in Seth Ward but in the big downtown sanctuary of Plainview First Baptist Church. The Dean brothers came with their wives—both marriages have lasted more than thirty years—and children, and they put a good face on things. But they stayed with different relatives and didn’t sit together at the funeral.

In a town like Plainview, whose best-known favorite sons have been professional football players with such names as McCutcheon, Sisemore, and Howton, and whose biggest nonagricultural industry is Wayland Baptist College, a national entertainment figure like Jimmy Dean is a hero by definition, and the story of his local enterprise remains a saga. Most people still speak well of Jimmy Dean and regret the “bad advice” he must have had along the way.

Troy Pritchard is one of those. Back in 1972, before Troy left the sausage firm, he warned Jimmy that the time would come when he would “get crossways with his brother.” Now Pritchard feels vindicated, but he takes no pleasure in the outcome. After he left the company, Troy didn’t see Jimmy again for ten years, until they shook hands at Ruth Dean’s funeral. But they didn’t really talk. He still wishes Jimmy would call him sometime.

Fryar Calhoun is a native of Plainview who lives in Berkeley, California.

- More About:

- Business

- TM Classics

- Sausage

- Longreads