This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

Last November 7, a slow Monday, Dennis Cozby worked alone on his partner’s regular day off. Just after 8 p.m., the Dallas patrolman made a routine swing down Grand Avenue. For years this black ghetto southwest of Fair Park has exceeded all other sections of Dallas in violent crime. The windows and doors of liquor stores wear braces of thick iron bars. Armed guards walk the aisles of supermarkets. Vacant lots are a sea of broken glass, discarded furniture, rained-on trash. Near Grand’s intersection with Lamar, the ramshackle houses yield to squalid apartment complexes. Boarded up in foreclosure, one sits behind a security fence erected to keep out arsonists and thieves. The Vacancy sign of another emphasizes a wall in which every window is broken out. Still, these streets and parking lots throb with laughter and music at night. A fourteen-year veteran, Cozby had used his seniority to win this inner-city beat; its appeal to him was “activity.” Cozby, who often lit up a fresh Grenadier stogie while making an interrogation or a bust, had a nickname in the ghetto. The black residents called him Cigar.

When the white cop turned onto Cleveland, he actually entered the beat of other officers. But the beats are so small and heavily patrolled that the police territories lose all but bureaucratic distinction. He saw a thick-necked, muscular young black man saunter down the sidewalk of a suspected “drug house”—or sales outlet—and mosey away from the curb in a 1976 Cadillac Seville. Cozby doesn’t assign traffic control the highest priority; taking the time to work a car wreck sets his teeth on edge. But random street busts often rely on the well-played hunch. By driving on the wrong side of the street, the man behind the wheel of the Cadillac handed the cop his probable cause. Cozby turned on the lights, and anything slow and ordinary about that Monday shift evaporated in the cool night air. The Cadillac zoomed through a stop sign and careened around the corner on South Boulevard. The chase was on.

Michael Frost, 20, had a street name of his own. People called him Fleabag. He had a police reputation as a juvenile gang leader, drug dealer, and burglar. At fourteen he shot and wounded a girl named Twinkie, perhaps accidentally, though certain officers doubt it. A year later he was a suspect in the murder of a newspaper truck driver. In 1981, after witnesses picked him out of a photo lineup, he was charged with the much-publicized robbery and murder of a white insurance auditor and urban pioneer named Scott Woods. Later a grand jury no-billed him, and another man confessed to the crime. The same year, Frost was charged with shooting another black man and then pitching the gun to a friend, who for good measure shot the victim again. Prosecutors dismissed the attempted-murder charge when the victim subsequently died in another gunfight.

Then, in 1982, the grand jury indicted Frost for aggravated robbery. In the plea bargain, the young man acknowledged that with the help of an accomplice he had battered a nearby apartment dweller with a shotgun and relieved the man of his pistol, $10, and a bag of marijuana. For that he got ten years’ probation. He neglected to keep appointments with his probation officer and to make restitution and to pay his court-appointed lawyer’s fees. He failed to attend his court hearing on a misdemeanor charge of evading arrest. If Michael Frost had made the drug buy that Cozby suspected, the search that came later failed to produce any evidence. But Frost had good reason to dread his next police interrogation. Just three weeks before Cozby turned on the lights of his car, the state had filed a motion to revoke Frost’s probation and the city had filed another warrant for his arrest. Fleabag was on his way to the joint.

Frost had a seventeen-year-old passenger, Lonnie Leyuas, in his car that night; apparently he clung to the door, catatonic with disbelief and fear. After a two-block run Frost wheeled around the corner on Parnell. Cozby briefly bumped the siren. Two Dallas County deputies who were serving warrants in the area saw the lights and joined the chase, but they were on a different radio frequency; Cozby thought he was on his own. He saw the Cadillac shoot up the drive between the stained plaster walls of the KK apartments. A less aggressive cop might have acknowledged the danger of being alone and waited on reinforcements before risking the hostile potential of that enclosed lot. But caution and passivity have never been part of Cozby’s style. Though he requested a backup, he had to rely on a series of desperate snap judgments. From the time his call hit the air, his contest of wills with Frost lasted just thirty seconds.

The following is Cozby’s hotly disputed account of what happened next. “The way the guy was acting,” he told me, “I thought the car was stolen. I expected him to take off on foot. He angled the car into the lot, and I pulled up right behind him. I came out with my gun drawn. Frost stood up on the ledge of the door. He never said a word. I told him, ‘Hit the ground, face down, hit the ground.’ No response. I told him to get up against the fender with his hands on the hood. He just stared at me.

“Standing up there, he had the height advantage, and he had leverage. When I got close to him, he jumped off the car and grabbed the gun with both hands. I controlled the trigger and never lost my grip, but he was lashing it back and forth, from side to side. He kept trying to get the barrel aimed at me. All the time, he butted me in the face with his forehead. Bang, bang, bang. I’ve never been up against anybody that strong. He drove me backward like a football player shoving a blocking sled. We hit a parked car, which knocked the wind out of me, and he bent me back over the trunk. My vision was blurred. I thought I was going to black out. I was losing that fight, and he wasn’t going to let me walk away from it. He meant to kill me with my own gun.

“I was able to wrestle the muzzle back toward him and get off a shot. I thought I’d missed him, because if anything, he just got stronger. He drove me backward another fifteen or twenty feet. We hit the patrol car so hard it caved in the front quarter panel. I twisted the gun back around and fired again. This time, he crumpled and hit the ground on his hip. The deputies ran up then. We couldn’t see any blood on Frost. He was conscious and still moving around, so one of the deputies handcuffed the guy. It wasn’t me. I was in a fog. In fourteen years I’ve never been in a fight that violent. My uniform was torn. I was hurt and sore and thinking, ‘Thank God I’m not dead.’ ”

We’ll never get to hear Michael Frost’s side of that story. He died at Parkland Hospital two and a half hours later, during surgery for two point-blank gunshot wounds. But the parking lot was filled with apartment tenants, among them members of the victim’s family. Frost’s last run from the Dallas law had carried him home. The black crowd raged around the white officers at once. “You didn’t have to shoot him!” somebody cried. Then the flash-point accusation: “They shot him while he was handcuffed.” Rocks and bottles started flying. With guns drawn, Cozby and the two deputies yelled warnings at the crowd to stay back. Though more squad cars and an ambulance arrived quickly, the situation was already out of hand. Police regulations prohibited Frost’s mother and siblings from trying to comfort the dying youth. Investigators worked fast, stretching their tape measures, while other cops clung to the harness leashes of agitated, barking German shepherds. Grim and nervous patrolmen stood guard with the stocks of twelve-gauge shotguns propped on their hips, barrels pointed at the sky.

Under a flood of TV lights, the crowd clamored around the Channel 8 reporter with wildly differing eyewitness accounts. “I had no way of assessing their credibility,” Byron Harris of WFAA-TV later said, “and I had fifteen minutes to decide how to play the story. We were afraid that whole side of town would go up in flames.” In the report that aired at ten o’clock, a police spokesman recounted Cozby’s version of the episode. A black teenager said he saw the cop fire the gun while Frost was defenseless, falling down. Byron Harris couldn’t put the fury of the crowd out of his mind that night, or the certainty of its condemning chant: “Seeeegar! Seeeegar! Seeeegar!”

In the days that followed, sixteen-year-old Brenda Frost told the Morning News that she saw Cozby hit her brother with a nightstick. “Michael fell into him. That’s when he shot him,” she said. “Michael landed on his chest. He handcuffed him. Then he kicked him over and shot him again.” At a packed meeting in the Martin Luther King civic center, Errol Sabbath, 12, described the same sequence for more than a hundred angry people, adding that Frost jumped out of the car with his hands up. Yet Edward Frost, 14, told the same gathering that he watched Cozby beat his brother with a club, then handcuff him, then shoot him twice in the back. Lonnie Leyuas, who from inside the Cadillac had the closest view of the struggle, had given an account the night of the shooting that matched Cozby’s in detail. The pathologist reported that Frost died from two bullets fired from within six to twelve inches of his abdomen. There was no evidence of any blows to the victim’s head. He had powder residue on both hands, which suggests that they were very near the gun.

The conflicting testimony didn’t stop Dallas city council member Elsie Faye Heggins from demanding Cozby’s immediate dismissal. Heggins, who has since resigned to run for county office, called for an inquest by a black coroner and discredited the independence and authority of the Citizens/Police Relations Board, which reviews controversies and makes nonbinding recommendations to the city council. Later Heggins tempered her assessment of the particular incident but continued to raise the specter of the ghetto riots in Watts and Detroit two decades ago. Yelled at by black activists while making a public appearance in support of minority recruitment, police chief Billy Prince called the Heggins statements irresponsible but heeded demands to transfer Cozby and his partner to another beat. Prince called Cozby into his office and told him to keep on doing his job. But within the Patrol Division, assistant chief Leslie Sweet kept wondering if Cozby could ever again respond to an emergency with the same speed and decisiveness. He recommended a transfer to the Criminal Investigation Division, a move that Cozby turned down. Expressing fears for Cozby’s safety, Sweet wanted his veteran off the street.

Chief Prince had some good news for Dallas at the end of the year. The city’s crime rate fell off 7 per cent in 1983, the largest decrease since 1971, and violent crime was down by 12 per cent. Arrests were up by 11 per cent. But at what cost, and through what means, was this law and order maintained? The most alarming statistic at year’s end was the 75 per cent increase in the use of deadly force. During 1983 Dallas cops shot 28 civilians and killed 15, a death toll exceeded only in New York, with 31, Los Angeles, 25, and Chicago and Houston, both 16. The carnage in Dallas wasn’t entirely one-sided. Two cops were shot and killed and two others critically wounded that year.

Police officers are a free society’s hired guns. In return for that dangerous service, we grant them windows of legal and moral exemption. Their definitions of self-defense and standards of civilized restraint aren’t quite the same as ours. When cops’ lives are even remotely threatened, they receive the benefit of every doubt. Some drunk and depressed old man fires a despairing shot from a .22 at the crowd of officers telling him to put the gun down; a fusillade from Magnums and riot shotguns ensues. Sad but justifiable, the grand jury concurs. Society’s protection against the miscreant cop lies in the screening of police candidates, the individual discipline instilled by training and experience, the diligence and good faith of department superiors, and, in the end, the process of indictment, trial, and conviction—the criminal justice system itself. The problem is, any system tends to take care of its own.

Whenever a police department’s use of deadly force jumps up dramatically, as it did in Dallas during 1983, two broad conclusions are quite readily drawn. Either the cops have gone berserk or conditions on the street have deteriorated to the point of civil insurrection. And with public leaders likening the situation to the urban race riots of the sixties, in Dallas each of those prospects is equally troubling.

Many residents who recall the crackling tension in South and West Dallas during those years wonder why the city didn’t blow up then. Because of the threat of brutal and wanton firepower, critics of the city and its police force reply. The emotional connection between police violence and social injustice toward black people is a price that history exacts from all American cities, especially in the South. We like to think that Dallas has changed for the better, that its politics have moderated, that its race relations have cooled down. But the bottom line of the 1983 figures has a way of standing out. Nineteen of the 28 victims of police gunfire were black, and in all but three of those cases, the cops were white. The department could argue that such figures are deceptive. Though only 29 per cent of the city’s population is black, last year 61 per cent of the people arrested for violent crimes were black. And with a police force that is 85 per cent white, the numbers just naturally shake down. But as one of the activists put it, the city and its police department could devise all sorts of studies and statistical analyses; meanwhile the black community had bodies in the ground.

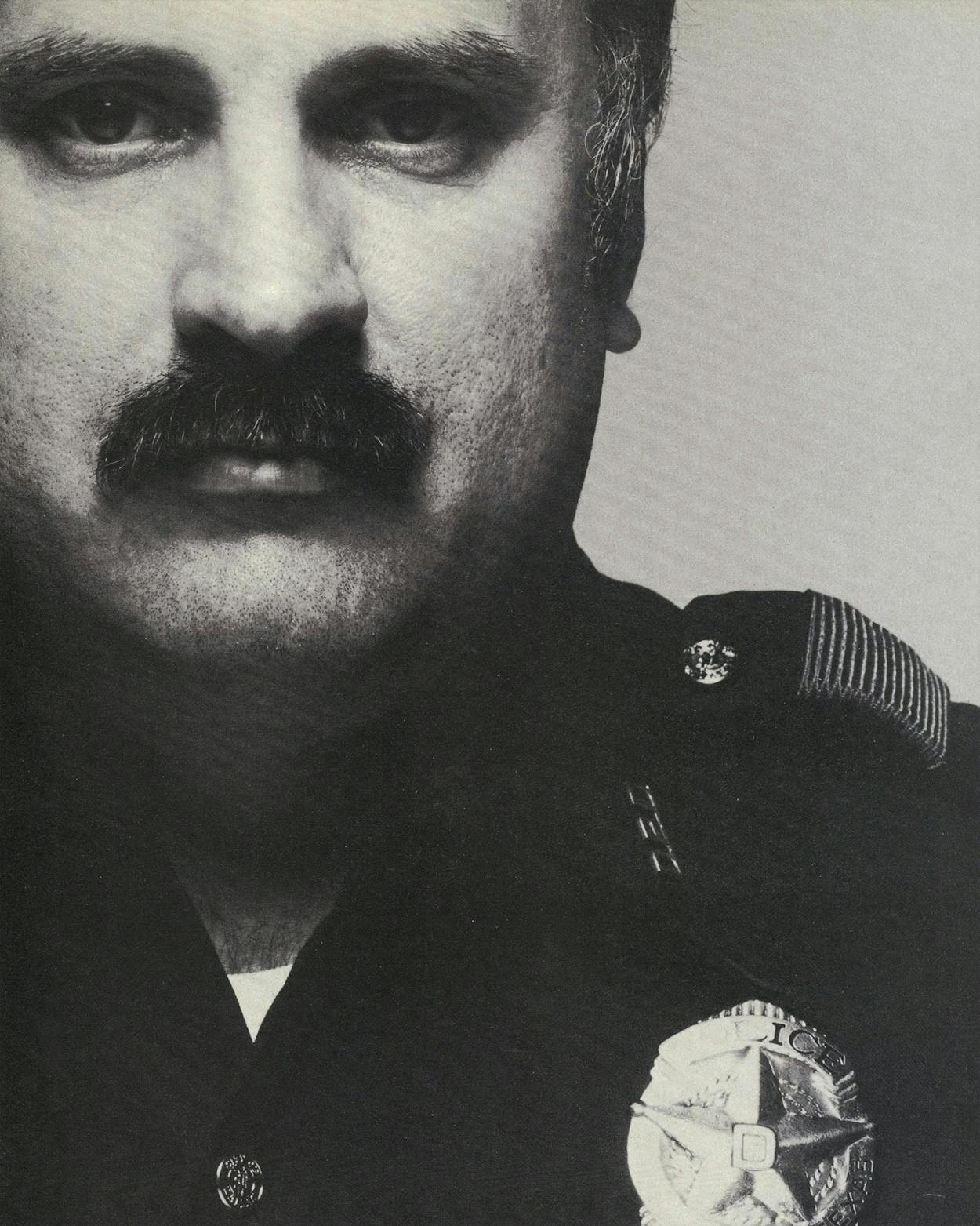

The result was a beam of intense heat focused on Dennis Cozby’s bald head. The controversial shooting happened late in an already tense and troubled year. In addition there were the matters of his individual statistics and flamboyant style. Police records revealed that he had fired his gun at more suspects than any other officer on the force. In fourteen years he had shot at eight people, wounded two, and now killed three. The previous killing had happened in 1976, when a burglar ran from Cozby toward a door guarded by a female rookie officer. Unsure of how the rookie would react, Cozby shot the burglar in the back and killed him. According to investigators, it was a clean, or justified, shooting—perhaps the most chilling expression in the law enforcement trade.

Cozby was no faceless blue suit never heard from before. Residents along Grand Avenue told stories of Cozby’s cruising through the apartment parking lots with soul music blaring from his bullhorn. They said he gave children candy in exchange for information about the suspects whose mug shots were lined up on his dashboard. One cop who worked the area said that black suspects dropped the name of Cigar in the same way that lawyers detained for traffic violations might mention their social acquaintance with Chief Prince. In the police department Cozby had another nickname. His own colleagues called him Mad Dog.

Cozby’s visibility hadn’t been limited to his beat. Motivated by ego and occupational pride, he had never dodged the press before, and now he paid for his high profile. He insisted, for example, that on the night of November 7 he had engaged in mortal struggle with a man who was a total stranger to him. After it happened, he never went near Parnell Street again. But Morning News reporter Doug Swanson found tenants who said that Cozby had provoked and harassed Frost for years. “Residents of the KK apartments say Cozby still comes around, wearing sunglasses and a sneer,” wrote Swanson. Cozby couldn’t believe that reporters would even listen to those people. He wasn’t the one with a criminal record. Once upon a time, a cop’s word in Dallas was almost law.

I met Dennis Cozby four years ago while researching an article about tough inner-city police beats (“The Beat,” Texas Monthly, May 1980). Back then Cozby’s beat centered on the redneck and biker hangouts of Samuell Boulevard, but since the bars didn’t heat up until late in the evening, he was free to roam other Central Division trouble spots for most of the shift. He made regular forays through the Grand Avenue beat. By all counts, that was the scariest concrete I had ever seen. The apartments along one six-block stretch had accounted for 22 homicides the previous year; security guards walked the lot of the biggest complex with loaded shotguns. Chewing bubble gum while smoking his cigar, Cozby barged with calculated nonchalance into places and situations that tied my stomach in knots.

He rode herd on the white bar fighters and black pimps with evenhandedness and humor. I thought he was cynical and ornery as hell, but I never saw him do anything brutal. Unlike some of the Dallas cops I met, he didn’t indulge in racist invective. Nor did he exhibit the preoccupation with firearms characteristic of his trade. In my presence he never threatened to bring his gun or even his nightstick into play, though I watched him fight burly and angry fellows one-on-one to make arrests. The revolver on his hip, a standard .38, was a mute and grim reminder. The fear that he aroused in suspects, especially black suspects, seemed largely symbolic. In a city whose cops for decades had maintained a tradition of the Iron Hand, he represented the collective power of the police.

Veterans of his particular chauffeur service hated Cozby’s smart-guy attitude and dreaded his diligence. Yet the prisoners who knew him didn’t seem to expect imminent bodily harm. They weren’t afraid to talk back. Cozby hassled folks of bad reputation and suspicious behavior. He was in the business of taking people to jail. The Joseph Wambaugh dictum of street cops applied: You can beat the rap, but you can’t beat the ride.

Now, four years later, we had barely gotten past the initial pleasantries when Cozby made a swing by a two-story drug house on Munger. I would see that structure many times during our reacquaintance, and all through the bitter December cold snap, the door to the upstairs apartment stood wide open. A black guy on the porch saw the police car and unwisely bolted up the red stairs. Undeterred by his recent experience with blind chases after suspects of unknown crimes, Cozby leaped from the car and dashed openhanded across the lawn, up the stairs, three strides ahead of his partner. “Bring the flashlight,” he called down after a while.

At the top of the stairs the perspiring fugitive stood with his palms propped against the wall, staring down and muttering grimly. In the same posture a much larger black man wearing a crumpled fedora looked around with the wan interest of someone caught in the wrong place at the wrong time. Cozby searched the floor with the flashlight till he found a cellophane packet containing the latest craze in Dallas street drugs, T’s and blues. The T’s were an oblong yellow painkiller called Talwin; more often lavender in color, the round blues were an antihistamine called PBZ. Melted down in equal proportions and injected into the bloodstream, the prescription drugs combine to simulate heroin. The pills sell for $15 a pair, which is cheaper than a pop of real heroin.

“It’s changed since you were here before,” Cozby told me. “These aren’t kids smoking dope out behind the honky-tonk. All we’re seeing now is junkies, most of them ex-cons.” He looked around at the large fellow in handcuffs beside me. “What did you do your time for?”

“Oh, ah, counterfeiting,” said the man.

“Hah,” said Cozby.

He has a way of carrying on mild conversations with prisoners one minute, then referring to them like tagged objects in the property room the next. At the Dallas County jail, he removed the big man’s handcuffs and let him take his place in the booking line. Cozby grabbed the prisoner’s forearm and showed me his scarred and swollen wrist. “Look at that,” he said. “They shoot themselves in the arms till they can’t find a vein, then they go to work on the wrists. Shoot themselves in the neck. In the scrotum.” He laughed harshly.

In the stream of cops and deputies and jailers, he lightened the mood and revived our previous, more genteel conversation. “So you got married since I saw you last,” he said. “What does your wife do? She a writer too?”

I almost blew the line. Life doesn’t serve many opportunities to cause a little stutter in the heartbeats of everyone around you. But I paid him back for some of the shocks he had gleefully sent through me. I laughed and cleared my throat and clapped him on the shoulder. “No, Dennis,” I said loudly. “She works for the American Civil Liberties Union.”

Cozby’s small brick home in East Dallas had a realtor’s sign in the front yard. He and his second wife, Debbie, had separated. He didn’t attribute their difficulty to the Frost killing and its attendant publicity. That trauma mostly affected his children. His wife had a career of her own now, he said, and her company had asked her to consider a transfer to another city. Dennis had five and a half years to go to qualify for a pension while he was still young enough to pursue a new career, so he refused to leave Dallas. Then again, maybe it was just time. The divorce rate in the police profession is 50 per cent.

A small desk drawer in the living room contained the mementos of his career. A March 1982 feature in the Times Herald rather glowed about the work along Grand Avenue of the “Mad Dog and Blondie” tandem, Cozby and his partner Bob Kamphouse. A child’s comic cartoon of a rotund cop with a long cigar had come in the mail, before the Frost shooting, with a warm and grateful note from a woman who lived in the KK apartments. “I miss the good people in that neighborhood,” he said now. “They don’t want characters like Frost around. The old ones have it worst. They’re ripped off constantly and scared to death. Kamphouse and I made a difference down there. When we took on that beat, it had the worst crime numbers in town. That’s not true anymore.” Cozby is proudest of a September 1982 letter to Chief Prince in which narcotics investigators recommended Kamphouse and him for certificates of merit. Signed by every officer in that division, the letter cited 220 drug-related arrests between January 1 and August 31 that year—an average of 1.2 a night.

In announcing the city’s improved crime statistics for 1982, Prince told the Times Herald: “The presence of the police is more highly felt when you make traffic stops. The increased traffic enforcement has not only cut deaths and injury accidents, but I think it’s also a factor in the number of felony arrests. The burglars, thieves, and the people doing the robbing and stealing are not walking. They’re in cars, and we’re finding more of them.” When Cozby connected that silver Cadillac in the wrong lane of Cleveland with his suspicions of drug traffic in the residence alongside, and then turned on his lights on the pretext of a traffic violation, he acted at the behest of his superiors. Under common law, a citizen’s misdemeanor is never cause for a police officer’s use of deadly force, but in running away from those lights, Frost tipped the legal balance to Cozby. And if, as alleged, Frost resisted legitimate arrest with violent and life-threatening force of his own, he laid issues of criminal law to rest. Under the Texas Penal Code, Frost’s resistance would be justifiable only if Cozby initiated the violence by using greater force than necessary to make the arrest and if Frost could reasonably believe that self-protection demanded immediate use of counterforce.

“So the crunch,” I suggested to Cozby, “is whether you had any business getting out of that car with your gun drawn.”

“No, you don’t do that to John Q. Citizen on the street,” he replied, with some heat. “But nothing indicated that what I had here was a run-of-the-mill traffic violation. There were two of them and one of me. What was I supposed to do: say ‘Uh-oh, this looks bad,’ throw the car in reverse, and back the hell out of there? Frost was a young guy. If he was all that afraid of being arrested, he could have outrun me on foot. Or, like ninety-nine out of a hundred suspects in the same situation, he could have put his hands on the hood. But he was out to kill himself a cop. Everything that happened, he set in motion. He could be alive today. He might be doing time somewhere, but he wouldn’t be dead.”

Cozby said he had received a lot of supportive mail since the episode. Some of it, he added grimly, was worthy of the Ku Klux Klan. “I don’t know if it’s the history or the economy or the social change or the liberal gun laws—though every punk on the block can get his hands on something to shoot. But one of the facts of this profession is that Southern cities are the most dangerous places to be a cop. People in Dallas know that twenty-eight civilians were shot by police last year. That’s all they hear and read about in the news. They probably don’t know that Dallas cops were shot at fifty-two times in the same period. They forget that the last two cops killed in the Dallas–Fort Worth area were shot with their own guns. It hurts to build a reputation in the community for solid police work and have it torn down overnight. Sells newspapers, I suppose. But I’d rather have people think I’m some kind of vigilante gunslinger than have them come to my funeral.”

One night I asked Cozby if, with the benefit of hindsight, he would change anything about his handling of the Frost encounter. He threw back his head and replied, “Not a thing.” And during the evening he demonstrated how the episode had left his approach to police work fundamentally unchanged. It was Monday, and once again Kamphouse had the night off. At the intersection of Hall Street and Central Expressway are the Roseland projects, a sprawling red-brick complex inhabited by black tenants. Making a routine swing past the projects on his new beat, Cozby turned off Hall onto Roseland and saw an old Chevrolet parked along the left curb in front of a dim little hangout called the Empire Grill. The Chevrolet pulled away from the curb and angled up the street before us. “Hmmmm,” said Cozby, then he turned on the lights. The probable cause? Driving on the wrong side of the street.

This time, no high-speed chase ensued. There were four people, all black, in the car. Cozby radioed for a backup and told me, “You stay back here.” He saw the shoulders of one man squirm and hunch forward, as if he was stowing something under the seat. Standing in the middle of the street, Cozby stooped and talked to the driver with a broad smile on his face. He straightened up and struck a match with a flourish, then applied the fire to the tip of a fresh Grenadier. The backup squad car pulled alongside Cozby’s, blocking the street. To our rear, another driver honked his horn in aggravation and punctuated the necessary U-turn with a squall of tire rubber. Soon the four were standing out in the cold with their hands on the Chevrolet’s trunk. One, a teenaged girl to whom the experience was a novelty, looked around with dazed affability and often raised her hands. The three men communicated grimly with their eyes and kept their hands firmly on the trunk.

The red and blue beacons roved the stark brick walls and caught glints of seasoned resentment in the staring faces of people on the sidewalk. Others ducked their heads and hurried on. I have seldom felt more depressed than I did as I watched Cozby search the car. Many years ago he recorded his first fatal shooting on the same block. Chasing one party of a botched heroin deal, he rounded the corner on Roseland and ran inside the Empire Grill, where the black man turned on him, jammed a pistol in his midriff, and yanked the trigger three times. The Saturday night special misfired. Slower on the draw, Cozby pulled his revolver and killed him cleanly, as the saying goes. It could have gone either way. I wondered now if the locale touched a particular nerve of history in him. Or, after so many years on the same streets, do the busts and blood and adrenaline all run together?

He emerged from the Chevrolet and walked toward the other cops wagging two cellophane packets of T’s and blues. “Knew he had something under there,” he grinned, having satisfied his unofficial quota of one drug bust a night. Cozby knelt in front of the headlights and broke open a plastic cylinder; two syringes fell out. He recited Miranda to a gangling man in his mid-thirties while applying the handcuffs. After warrant checks on the others came back clear, he wrote the driver his traffic citation and prepared to let them go.

The two cops who had answered the backup call were both in their twenties. As they started to pull away, the rider rolled down his window and said, “Cozby? Sometime at the station I wish you’d sit down with me and catch me up on all these new drugs. T’s, blues, pills, hell, I hear about them. But I don’t know what they’re talking about.” Cozby beamed. He might face the censure of a troubled and changing city, but he still had the approval of his peers. They knew what kind of cop he’d been.

Driving toward the county jail, he looked back over the seat at me with an air of affirmation. “Junkies. Ex-cons. Almost every one with a history of violence. If they’re out of dope, they’re desperate. And if they’re high, they’re fearless.”

The prisoner frowned at the impersonal assessment. “Hey, I ain’t no junkie.”

“Oh,” Cozby grinned. “You just shoot up for recreation.”

“Well, yeah. Now and then.”

As often happens when an arrest proceeds without violence and unnecessary rancor, cop and prisoner warmed toward each other in that strange reflex of relief. They chatted cordially. “How much time did you do down there?” asked Cozby, referring to the joint.

“Eight and a half years. Didn’t get in no trouble, either.”

“You did eight and a half? My God. What was the original sentence?” It’s a kind of shoptalk. They do have a certain bond.

The man twisted his shackled hands and said matter-of-factly: “Thirty-five years.”

Cozby whistled. “Mercy. What for?”

“Aggravated robbery.”

Cozby slid me a triumphant glance. “Actually,” the prisoner reminisced, “it was my money, you see. I took it out on loan, and this other dude collected it for me, then wouldn’t give it back. So I commenced to pistol-whipping the dude. And on reflection, I took all his money.”

After hearing testimony from twenty witnesses, on February 6 a Dallas grand jury no-billed Cozby for the fatal shooting of Michael Frost. District attorney Henry Wade cited the coroner’s report as the conclusive evidence verifying Cozby’s account. The victim’s mother, Maxine Frost, responded bitterly: “There’s going to be five or six more killings like this if they don’t get that man off the street. What’s it going to take to keep him from shooting any other young black man? We’ll just let the good Lord take care of Cigar.” Black activists promised a stormy confrontation with the Citizens Police Relations Board, the advisory review panel that had been expanded to seat two more black members from South Dallas in the aftermath of the Frost shooting. Several witnesses, the activists promised, would condemn Cozby and refute the grand jury finding for the public record. An attorney for the Dallas Police Association said he didn’t “want to chill anyone’s right to speak,” but he mentioned that notes would be taken with the possibility of slander suits in mind.

Chillier still, on February 28—the morning of the public hearing—the grand jury indicted three of Cozby’s seventeen-year-old accusers for aggravated perjury, a felony punishable by up to ten years in prison and a $5000 fine. Lonnie Leyuas, the passenger whose statement the night of the shooting had supported Cozby’s version, was charged with lying to the grand jury when he changed his story and said that the cop shot the prisoner while he was handcuffed. Indicted for testifying that Cozby struck Frost with a nightstick were an apartment resident, Victor Franklin, and the victim’s sister, Brenda Frost. After that, witnesses who would speak for the public record became much harder to find. At the ballyhooed public hearing, only one activist had anything to say.

In a study commissioned during the furor over Cozby and Frost, the review board found “no pattern of abuse and no evidence of misconduct by officers” in the police department’s use of deadly force. The report recommended an ordinance that would assign investigation of citizens’ complaints to a more impartial authority than the department’s Division of Internal Affairs. In the most daring proposal—this was, after all, Dallas—the board urged a city and statewide ban on the sale of handguns. The study also suggested that foot patrols and storefront substations could help defuse ethnic tension and promote cultural understanding and that along with emphasis on “strategic withdrawal” from life-threatening confrontations, officer training should include more simulation drills of episodes that might lead to the use of deadly force. Out of the 28 shootings, the city’s analysis cited 7 cases in which police errors had exacerbated the situation. Although the commission found that Cozby failed to take cover and maintain an adequate distance from Frost, by the lights of the system, the shooting was perfectly clean. As for the jarring statistics, the report implied, 1983 was just one of those years.

To Chief Prince, the net result vindicated Cozby and, by extension, the entire force. To the angry and embittered black citizens of South Dallas, it represented one more squeeze of the old Iron Hand. The department’s fierce support of one corporal on patrol was more than the fortress mentality exhibited by all police officers when they come under public and media siege. By the definitions of the Dallas Police Department, Cozby had been a model street cop. His pursuit of crime was aggressive—though that standard of officer behavior is subjective at best and dangerously ill-defined. He was a proven and grizzled veteran. Superiors trusted his judgment in the heat of the fight. Even so, with the appearance of opportune political concession, the same superiors granted the least of the black activists’ demands. The same day that the perjury indictments came down, Chief Prince announced that Cozby had been pulled off the street.

Cozby now rides herd on a desk. His beat is 75 per cent paperwork. He wears a coat and tie, not the uniform blues, and arrives at the office at seven-thirty in the morning. In the general assignments section of the Criminal Investigation Division, he prepares, for court presentation, cases involving criminal mischief, felons in the possession of a firearm, and the like. As a detective, he’s starting at the bottom. To the chagrin of some in the office, he still smokes cheap cigars.

Cozby’s second divorce is final now. With joint custody of three children, he already felt the need to spend his evenings at home. As a patrolman on the day shift, he faced the workaday tedium of endless, uneventful driving around—stopping motorists with expired inspection stickers, for lack of anything else to do. “As day jobs go,” he described his new assignment, “this one’s a peach. It’s taken some adaptation. For one thing, my body and brain resist the notion that they’re supposed to sleep at night. I miss the excitement, sure. I miss the friends I made. Blacks that I arrested before have told me they’re sorry about the way this whole thing came down. But times are changing. So are people’s attitudes toward the police. If anything ever happened, no matter how clean and righteous, I’d have it all to go through again. I feel like I’ve done my time. My dues are paid.”

A good deal of his bitterness, he reminded me, is directed at members of my profession. “Mad Dog,” he muttered. “How catchy. Do you know the first time somebody called me that? It was in the peewee Golden Gloves. I was six years old.”

I used to think that when Cozby, the son of a Fort Worth fireman, finished his infantry tour in Viet Nam—where he was wounded three times—he chose to go into law enforcement because it was a socially commendable way of venting all that pent-up steam. He wanted to be on the world’s hot and hardened edge. Whatever his motivations then, he’s no trigger-happy redneck now. He comes to work every day with a sour and dogged professionalism. He perceives himself as a protector of the innocent and believes in the system that has taken care of him. “Righteous” is a word often heard from him. Because of those perjury indictments, he thinks the forces of good won out. They made it easier for him to come in off the street. As one spokesman for the department put it, he’s a company man.

Like most people, I am sheltered from the environment he moved in daily, and I dearly hope to remain so. But all the sordidness and inhumanities have to add up. He has the bleakest world view, the grimmest sense of human nature, that I have encountered in someone of my background and generation. Time and again, I’ve seen his darkest instincts about people proved right. When Cozby watched that muscular black youth saunter down the sidewalk on Cleveland Street that night, he didn’t know about the arrest warrant. But somehow he knew that here was another guilty party that he could throw in jail. Cozby was twenty when he graduated from the police academy and took on his rookie Central Division beat—the same number of years that trouble-prone black kid had on this earth. I don’t know if Cozby can even remember how he perceived life back then. If he could, maybe he would have more compassion for the expended possibilities of Michael Frost. Cozby hurts. He bleeds. I found in his emotional makeup every possibility except remorse. Recounting the experience with Frost fills him with such strong feeling that it’s hard for him to even say the kid’s name. “That scumbag,” he growled once, “who made me kill him.”

- More About:

- TM Classics

- Police

- Longreads

- Dallas