ON THE FIRST FRIDAY NIGHT of football season, Santa Fe High School’s bleachers were packed with straw-haired girls and sunburned boys in baseball caps and parents in T-shirts that said “Fix Your Eyes on God.” Beneath them, a spectacle was unfolding that seemed far grander than anything a Santa Fe Indians-Hitchcock Bulldogs game would normally merit. TV trucks and camera crews were descending from all directions on this small-town stadium, having come not for the spoil, but for the symbolism: This was the first game since the U.S. Supreme Court had handed down a devastating decision against the Santa Fe school district, striking down its longstanding tradition of school-sponsored prayer at football games. The ruling had touched a wellspring of emotion in Santa Fe, and as game-time neared, it was clear that the town’s indignation ran deep. Two men bearing large pine crosses across their backs stood in silent protest at the stadium gates, while a dark-eyed teenager walked among the crowd singing hymns and weeping, his Bible held aloft, as if he were seeking divine intercession. Defiance mixed with piety: On the crowd’s fringes, a tow-headed boy carried a sign high above his head proclaiming “We ought to obey God rather than men, Acts 5:29.”

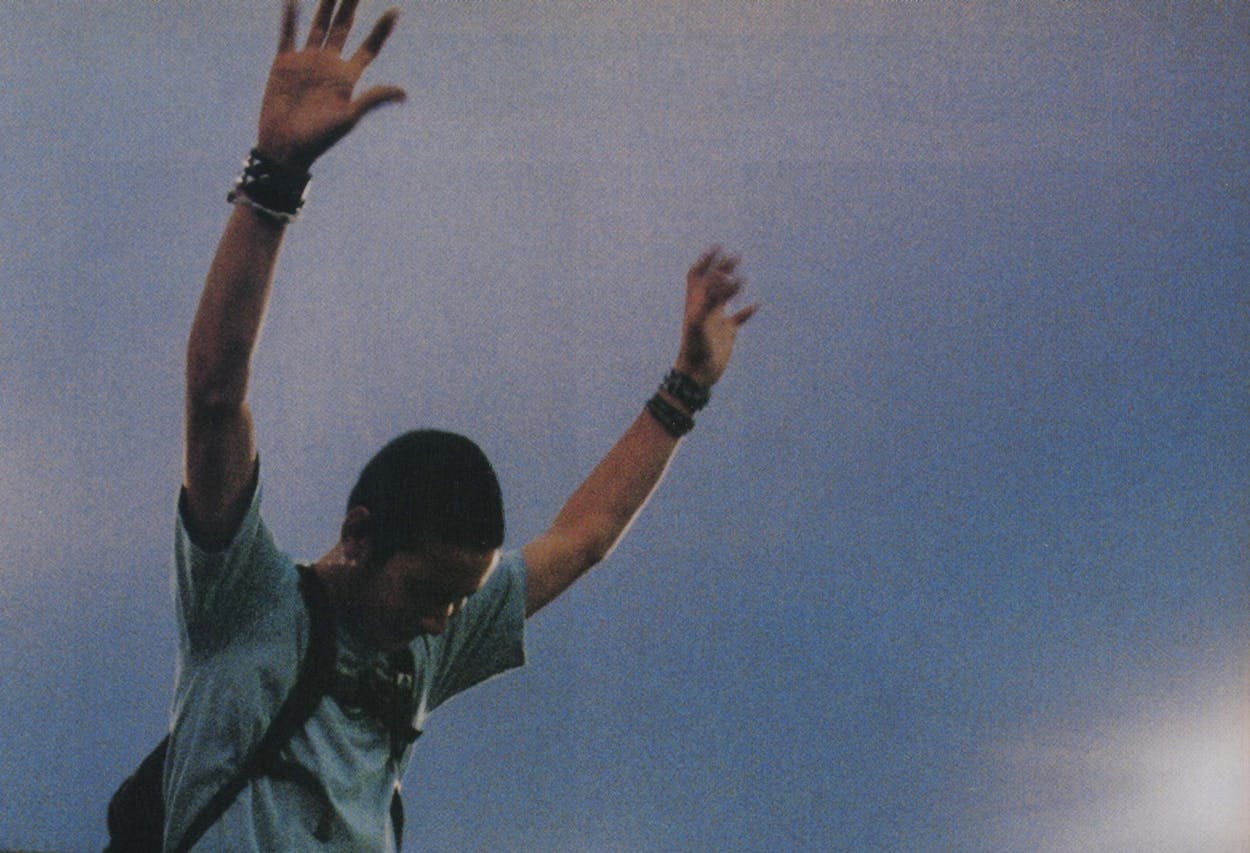

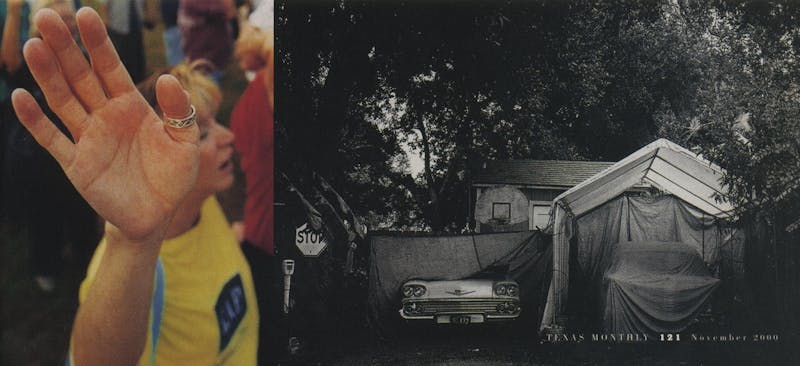

Faith and football have always gone hand in hand in Texas, where the gridiron is king, and especially in Santa Fe, a devout, largely Baptist town in western Galveston County where residents keenly feel God’s presence. A rural community of around ten thousand people, Santa Fe has become ground zero in the fight for school prayer, its June defeat before the Supreme Court having lent its barren stretches of salt grass and marshland an air of martyrdom. The battle that has raged here—turning friend against friend, neighbor against neighbor—has centered on the right to pray. But the prayer controversy is also part of a larger struggle over how great a role religion should play in public life, and in Santa Fe many think it should play a very large role indeed. It was a point Santa Fe made that Friday night from the bleachers, in front of the hum and whir of cameras: When the last notes of the National Anthem faded and the Fighting Indians ran onto the field, several hundred people in the stands bowed their heads and raised their hands skyward, their voices straining to be heard over cheers and air horns and scattered applause. Our father which art in heaven, hallowed be thy name. Thy kingdom come. Thy will be done in earth, as it is in heaven….

The battle over prayer began here when two mothers sued the Santa Fe school district in 1995 for what they saw as an undue presence of religion in the public schools: Gideons were distributing Bibles in the hallways, teachers were teaching religious songs to their pupils, and graduation ceremonies had taken on the air of Sunday worship services. Only one sentence in the fifteen-page petition mentioned prayer at football games, but it became the key issue in subsequent appeals and the sole complaint to be heard by the Supreme Court. The town’s five-year fight culminated with the Santa Fe v. Doe ruling, in which the high court held that students could no longer deliver prayers over school loudspeakers before football games: The practice violated the separation of church and state, the court ruled, and was inherently coercive. Though students’ right to pray on their own before, during, and after games is still protected by law, the decision has stirred deep emotions. This fall, it has triggered a grassroots movement for prayer in the stands across parts of Texas and the South, where pre-game prayer over the loudspeaker is tradition, as much a part of Friday nights as the opening kickoff.

In the wake of the Supreme Court ruling, Santa Fe has been championed as a symbol of a good, God-fearing Texas town that fought for what was right. But over the past several years, the town has waged a modern-day crusade that has revealed not only the best of intentions but also the worst of impulses. Those who have found themselves at odds with the town’s desire for more religion in the schools have been shunned, harassed, and even threatened—so much so that the two mothers who sued the school district did so anonymously, fearing for their families’ safety. Students who declined to take Bibles that were handed out at school were called devil worshipers; parents who dared to question the school’s pre-game prayer policy were deemed heretics. Those of minority faiths fared no better: This summer, the parents of the only Jewish boy in the school district, Phillip Nevelow, filed a $4 million lawsuit charging that administrators turned a blind eye to classmates who drew swastikas on his notebook, gave him the “Heil Hitler” salute, and ultimately threatened to hang him.

Prayer before football games is part of a much larger campaign in Santa Fe, one to “bring God back into the classroom” according to school prayer advocates. Many here argue that the secularization of schools—after decades of Supreme Court rulings removing morning prayer and the Ten Commandments from the classroom—has caused a moral crisis in both this community and the nation as a whole. They believe Santa Fe has been chosen for a purpose, and that purpose is to wage “spiritual warfare” against an increasingly secular and amoral culture. “We are warriors on the field,” said Pastor Terry Gibson, “and prayer is our greatest weapon.”

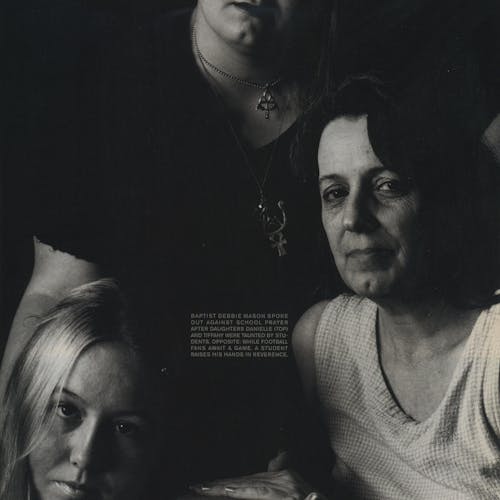

DANIELLE MASON WAS ELEVEN YEARS old when she was first accused of not being a good Christian. The youngest of four sisters who lived on a rambling four-acre lot on the south side of town, she was a reverent fifth grader, modeling herself after her sister Tiffany, who had entertained thoughts of someday becoming a nun. Most Sundays, the Mason sisters attended the biggest and oldest church in town, the First Baptist Church of Alta Loma, where they sat in its dark, wooden sanctuary and prayed in Jesus’ name. Danielle wore a thin silver cross around her neck and sometimes drew pictures of the apostles, carefully copied out of her candy-pink illustrated Bible. At night she would wind up her white music box with the pink trim and listen to its cheerful tune, “Jesus Loves Me,” as she drifted off to sleep.

According to Danielle, the week before Easter during her fifth-grade year, she gathered her belongings from her locker at the end of the school day and headed for the door. Several neatly dressed Gideons had set up a table nearby, and one of them approached her, proffering a Bible. She thanked him but declined the offer. Undeterred, the man pressed it into her hands. “God wants you to have this,” he said. “Jesus wants you to know him.”

“No, thank you,” she said. “I have a Bible at home.”

Other students in the hallway with the new red Bibles tucked under their arms stopped and stared. Again, the man offered her one.

“I don’t want it,” she said.

The students gathered closer. “Do you worship Satan?” one child asked. “Are you in a cult?” asked another. Danielle stared back at them, mute. Then the words came in a torrent of shrill voices. Devil worshiper. Atheist. God hater.

That was 1993, the year the Masons began to view their town with a growing sense of unease. Dan Mason, a cement contractor, and his wife, Debbie, had moved there fifteen years earlier, buying a modest spread of land and building their own home. Dan was a volunteer with the fire department and Debbie regularly attended school board meetings; every Sunday they opened their home to neighbors and friends from church and barbecued in the back yard until it grew dark. Santa Fe had always been a place where people were strong in their faith but not in their judgments, Debbie recalled, though in the early nineties, that began to change. Fundamentalist and evangelical churches had always played an important, if low-key, role in Santa Fe. But as the town grew from 5,413 residents in 1980 to 8,628 people in 1990, church rolls swelled, and the Ministerial Alliance—a coalition of local church leaders who would figure prominently in the push for school prayer—became more powerful, and more political. Several school board positions were soon filled with self-described Christian conservatives, who called the separation of church and state doctrine a “myth” and a misinterpretation of the Constitution. By the time the lawsuit was filed, the town’s mood had begun to shift. “It was all about who prayed the loudest, who went to church the most, who was the ‘better Christian,’” Debbie said.

Abstinence-only sex education classes were instituted. Juvenile literature by Judy Blume and Beverly Cleary was removed from the elementary school library (an effort to restrict students’ access to Harry Potter books is currently under way). And Danielle Mason was not the only student to have had a Bible forced on her or to be taunted for not taking one. “I was told by an administrator that if my girls would just take the Bibles, there wouldn’t be a problem,” Debbie Mason said. “My question was, Why were Bibles being handed out in the first place? That’s up to me and my church, not my school district.” There were also troubling rumors, never confirmed, that teachers were leading children in prayer before class and at lunchtime. After a particularly egregious incident—in which a seventh-grade teacher handed out flyers for a revival meeting to his students, then spent ten minutes of class time denigrating a Mormon girl’s religion as a cult—25 concerned parents and teachers met with an attorney from the American Civil Liberties Union to discuss whether the school district was promoting religion.

Word soon leaked that a lawsuit was in the works, and in 1994, the school board held a meeting to discuss whether to fight it. By that time the school district had begun to make changes, reprimanding the teacher who disparaged the Mormon girl’s religion and, in one case, instructing a teacher not to lead students in religious songs. The ACLU, however, took the position that the previous practices were part of a larger pattern of behavior in which the district gave a platform to religion. The charge sparked a heated discussion that night, in which one parent railed against Madalyn Murray O’Hair and another lamented that “the devil is taking over the schools.” “My mind was reeling,” Debbie said. “We needed books. We needed teachers. Why were we talking about this?” More disturbing, she said, was the ugliness of the mood that night. When a Catholic mother took issue with school prayer, a woman behind her called out, “Catholics aren’t Christians anyway.” During a recess, a woman approached Debbie to inquire what religion she was. “A school board member leaned over and said, ‘Don’t worry. She’s Baptist—she’s one of us,’” Debbie recalled. “And I thought, what does ‘one of us’ mean?”

In April 1995 the ACLU filed Jane Doe v. Santa Fe Independent School District, a wide-ranging civil rights lawsuit that sought to “remind [the school district] of the value of the separation of church and state and the need to prevent the government from endorsing one religion over another.” It cited eleven infractions—from Bible distribution, to a baccalaureate service led by a Baptist minister, to prayer before football games—that had “the primary effect of advancing, sponsoring, promoting, endorsing and/or encouraging religion and foster[ing] excessive entanglement by Santa Fe Independent School District with religion.” Identified only as Jane Does, the plaintiffs were described in court filings as two mothers—one Catholic, one Mormon—who each had two children attending Santa Fe schools.

Secrets are hard to keep in Santa Fe, and as those few telling details circulated around town, so did speculation about who the Does might be. Debbie Mason’s daughter Jennifer—then an honor student and a student columnist for the Texas City Sun—remembered adults in her church exhorting her peers to find out who the Doe children were so they could be saved. (A youth minister later told his young parishioners that their persistent attempts to discover the Does’ identities were wrong.) At school, students began viewing their Catholic and Mormon peers with suspicion, harassing and ridiculing those who seemed likely suspects, much in the same way they had vilified the children who had not taken Bibles. Around town, questions about religious affiliations became the norm, as did requests to sign petitions supporting the school district. “The petitions were an attempt to ferret out the identities of my clients,” said Galveston attorney Anthony Griffin, who represents the Does. “Anyone who didn’t sign them went down on the town’s McCarthy list.” Even school district employees were involved. So severe was the problem that the presiding judge in the case, U.S. district court judge Sam Kent, threatened them with “the harshest possible contempt sanctions” and “criminal liability” if they did not cease their investigations.

The daughter of one Doe plaintiff, who spoke on condition of anonymity, believes that this “witch hunt” was the result of a fundamental misunderstanding. “Kids were misled by clergy members and parents who said that we were trying to put an end to religion, that we were trying to outlaw prayer,” she said. “Our intention was just the opposite: We wanted to guarantee religious freedom for every student by keeping religion out of the hands of government. We were fighting for religious freedom, not against it. But people in Santa Fe couldn’t understand that.” Now a college student, she remembers the spring of 1995 as “a very fearful time,” when fellow students called the Does Satanists and threatened to burn crosses in their yards if their identities were ever discovered. “My friends would say terrible things about the Does,” she said, “and I would sit there thinking, ‘If you only knew.’” She recalled visiting a friend’s church one Sunday and hearing a Baptist preacher deliver a heart-stopping sermon about the lawsuit. “He got people very riled up,” she said, “and it was terrifying.”

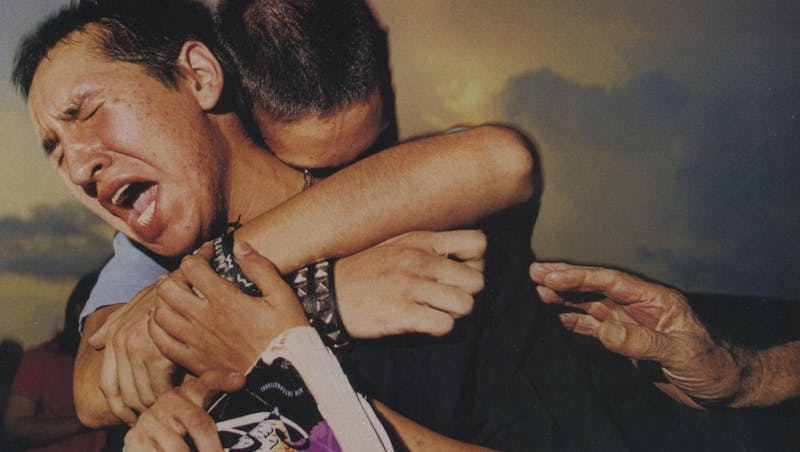

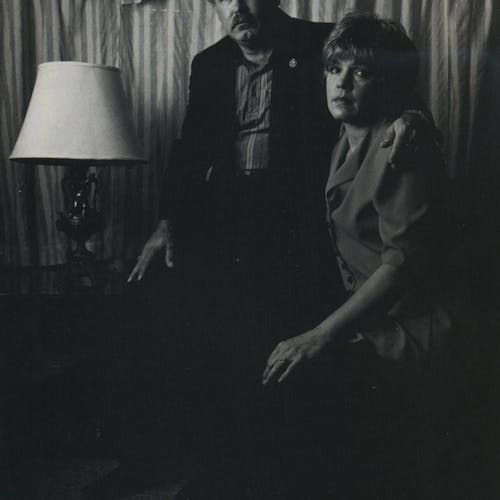

A good number of people suspected that Debbie Mason, who had been outspoken in her support of the Does, was behind the suit; acquaintances began turning their backs on her at the grocery store, and soon her husband had to look for work outside Santa Fe. “I was called a lesbian, a Communist, an atheist—everything you can imagine,” Debbie said. There were also phone calls that came late at night, one with the chilling admonition to “watch your children’s backs.” At times, it was too much for her daughters to bear. One afternoon she found Tiffany, distraught over the treatment of a Mormon friend at school that day, throwing her Bibles and her collection of cross-shaped earrings in the trash. “If this is what Christianity is about,” she said in tears, “I don’t want any part of it.”

SANTA FE LIES ON A HARDSCRABBLE stretch of Texas Highway 6, along the old Santa Fe Railroad line, where the bayous on the fringe of Galveston Bay yield to firmer ground. This is a town without a center, a sprawling settlement of frame houses and trailers and prefab suburban homes, whose patchwork of old pastures and fallow farmland is slowly reverting to wilderness. Santa Fe sprang into existence in the late seventies, when the dairy towns of Arcadia, Alta Loma, and Algoa incorporated and named themselves after the railway line connecting them; it soon began luring shift workers from Texas City’s refineries and petrochemical plants, holding out the promise of one-acre lots and simpler rural living. Besides football and the rodeo, there is little here by way of distraction. Teenagers still hang out at the drive-in burger joint after school, and gossip is shared over coffee at the Busy Bee Cafe, a round-the-clock diner where photos of grinning customers with their prize livestock line the wall and everyone knows each other by name. Santa Fe has the look and feel of the 1950’s, and in many ways, that decade before the social upheaval of the sixties remains the ideal. “We had a kinder, gentler society back then,” said John Couch, a school board member who fought for abstinence-based sex education. “A lot of people here wouldn’t mind taking a step back.”

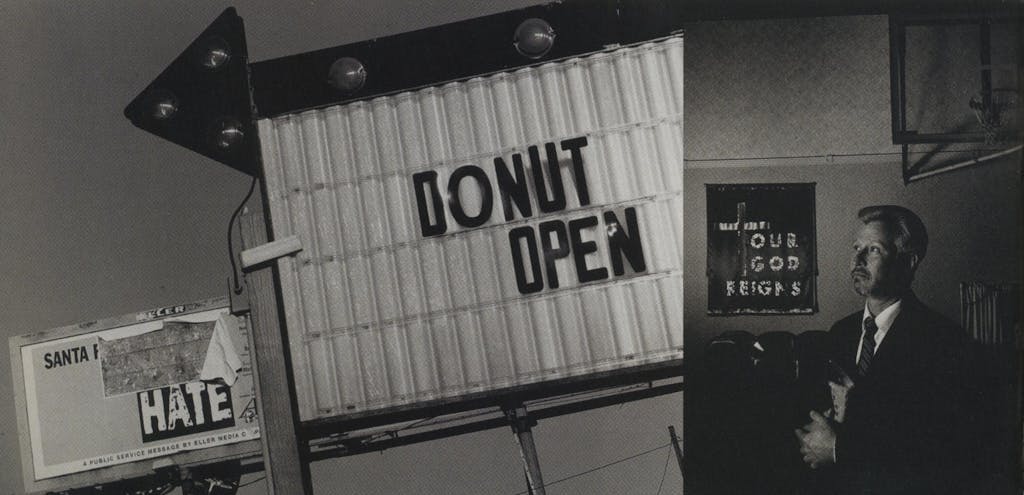

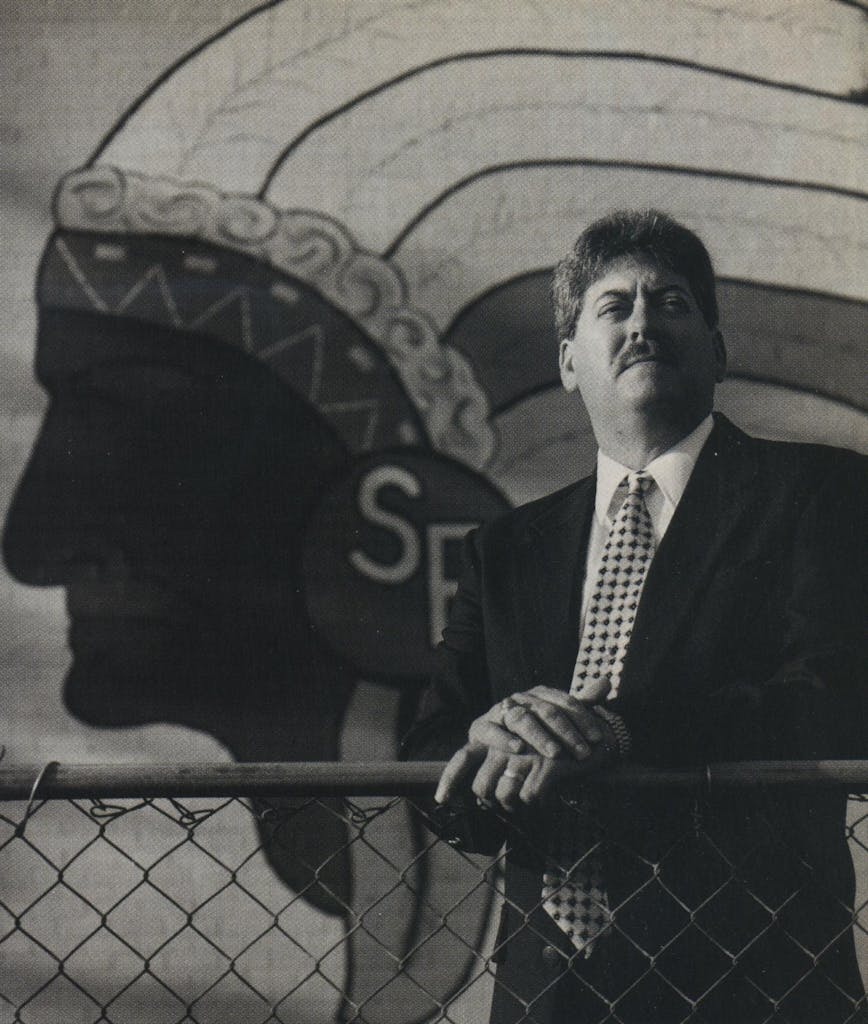

An engineer at a local chemical plant, Couch has become one of the most influential men in town—more so, perhaps, than any minister or politician. (“Most people in Santa Fe can’t name our city council members, but everyone knows who sits on the school board,” explained one mother. “That’s where the power lies.”) Couch, a middle-aged family man with a sober and deliberate manner, was one of the first in Santa Fe to narrow in on prayer as the key issue in the Doe lawsuit. “Most of the complaints in the suit were absurd,” he said. “We were accused of letting Gideons on campus and forcing Bibles on kids. Nothing like that happened. The people who filed this suit, like many left-wing organizations in this country, wanted to make the word ‘Jesus’ taboo and take away our children’s right to pray. And we refused to stand for that.” It was a message that resonated throughout this community, where circuit preachers and revivals have been making their way up what is now Highway 6 for more than a century. Here, church signs proclaim Santa Fe’s abiding loyalties, from the “Jesus Is Lord” sign at one end of town to the even larger “Abortion Stops a Beating Heart” billboard on the other. Another exhorts residents to “Pray Without Ceasing.”

Nowhere are these disparities more painfully on display than on Friday nights, when the color divide across the line of scrimmage is often black and white.

Until the lawsuit was filed, however, Santa Fe was known less for its religious zeal than for its racial intolerance. Santa Fe was thrust into the spotlight in 1981 when the Klan held a cross-burning demonstration here, and rumors persist that the Klan still meets by a spreading oak tree on the west side of town, thought to have once been the site of a lynching. Some locals believe that a blaze set at a low-income housing complex in 1993 was racially motivated. But nothing has stained the town’s reputation more than a 1997 incident, in which several teenagers terrorized a busload of African American girls—junior high students from La Marque who had come for a basketball game—by rocking their bus back and forth, yelling racist epithets, and threatening to hang them while brandishing a piece of rope. African Americans stay clear of Santa Fe: Though the three neighboring towns of La Marque, Dickinson, and Hitchcock are racially diverse, the last census counted only nine black residents in Santa Fe. Nowhere are these disparities more painfully on display than on Friday nights, when the color divide across the line of scrimmage is often black and white.

Santa Fe ministers have suggested that one way to help heal the community’s wounds is through prayer, but thus far, no such transformative powers are evident. If anything, the politics of prayer has opened even deeper divisions. Pastor Terry Gibson, who as quarterback for the Santa Fe Indians in 1967 bowed his head before every game, summed up the town’s sympathies. “We had prayer before football games in Santa Fe when I was growing up and when my parents were growing up,” he said. “This has been right in this community for generations. Who are the courts to tell us to change?” Like John Couch, he believes that the time when America’s children were allowed to pray in school was a better time than today. He pointed to 1962, the year the Supreme Court barred states from requiring students to say morning prayers in Engel v. Vitale, as the beginning of a slow erosion of the nation’s morality. “If you look at the decay, the violence, the falling test scores, so much of it began when school prayer was banned,” he said.

“If you divorce morals and religion from public life, you’re going to have chaos,” agreed Couch. He and former school board member Mike Lopez, a self-described “foot soldier in the culture war,” saw the Doe suit—and its desire to eliminate the last vestiges of school prayer—as a cause the district must fight vigilantly against and tried to get the archconservative Rutherford Institute to take on their case. “We’ve had activist Supreme Court justices come along in the past forty years, and rather than interpret the Constitution in a strict sense, they’re rewriting history,” said Couch. “In the nineteen-forties they coined the term ‘separation of church and state,’ but that’s not what our founding fathers intended. They wanted to guarantee freedom of religion, not freedom from religion.”

The first legal skirmish in the Doe suit was over school prayer: Judge Kent issued an interim order in May 1995 stating that student-led prayer was constitutional at football games, as long as it did not mention specific deities and was not a “religious sales pitch.” It was a victory for school prayer advocates, since no federal judge had ever upheld the right to pray publicly at high school football games. But the board was still dissatisfied; Kent’s stipulation that such prayers be “nonsectarian” and “nonproselytizing” was seen as tantamount to censorship. “The court was telling students how to pray,” said Couch. More important, said superintendent Richard Ownby, “The school district was being asked to monitor student speech for religious content. We didn’t want to be in the business of telling students they couldn’t say a prayer if they wanted to say a prayer.” In response, the board consulted with attorneys and crafted a carefully worded policy reflecting a legal theory being advanced by school prayer advocates nationwide: School prayer is a matter of free speech, not of religion. Students themselves would vote on whether they wanted invocations delivered before football games; if the vote was affirmative, they would elect a spokesperson to deliver the prayers for the season. This way, student speech was free of government involvement, the board reasoned, and was not hamstrung by Kent’s ruling.

Attorney Anthony Griffin, who took on the Does’ case in 1995 for the ACLU and would argue on their behalf before the Supreme Court, saw this policy as the beginning of a slippery slope. “If a student vote could privatize prayer,” he said, “then students could vote for prayer in the classroom, and public schools could evade every one of the Supreme Court’s school prayer cases.” Raised a Baptist, Griffin had no reservations about taking on the case—despite heated criticism from his brother, who is an evangelist, and several devout co-workers, who regularly held prayer circles at the office in support of the opposing side—because he felt he was fighting for religious freedom. “Students may pray on their own anytime, anywhere,” said Griffin. “But at Santa Fe football games, students were being coerced to participate in a religious exercise that was clearly sponsored and encouraged by the school. Religious belief and expression is flourishing in this country because we have avoided others’ mistakes; we have not allowed our government to endorse religion or to interfere in religion. In Santa Fe, the will of the majority was being imposed on the minority.” Judge Kent heard testimony from both the Does and school administrators and ruled in 1996 that the district had violated the First Amendment by having allowed school-sponsored prayer and the distribution of Bibles on school property. Though the district had erred, Kent ruled, it was acting in good faith to correct such policies, and he declined to award any damages to the Does. Both sides appealed to the Fifth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, which delivered a ruling last February that proved to be a devastating blow to prayer proponents in Santa Fe. Student-led prayer was appropriate at graduation ceremonies, the three-judge panel ruled, since it is “a significant, once-in-a-lifetime event,” but football games, they added with scant understanding of Texas tradition, are “far less solemn and extraordinary.” Prayer before football games was unconstitutional, the court ruled, stating, “Football games are hardly the sober type of annual event that can be appropriately solemnized with prayer.”

The ruling was greeted with outrage in Santa Fe, and the school board vowed to take its case to the next level, voting 7-0 to appeal the case to the Supreme Court. “Pray Before It’s Illegal” trumpeted one church sign, in a common refrain. The battle was on, and if Santa Feans needed a martyr for the cause, they found one in Marian Ward.

“THERE’S A VERSE IN THE BIBLE THAT says, ‘Whether you eat, or drink, or whatsoever you do, do all to the glory of Cod,’” said Marian Ward, her blue eyes resolute. “And so, if I’m given a public platform, I must glorify God, even if the courts say otherwise.”

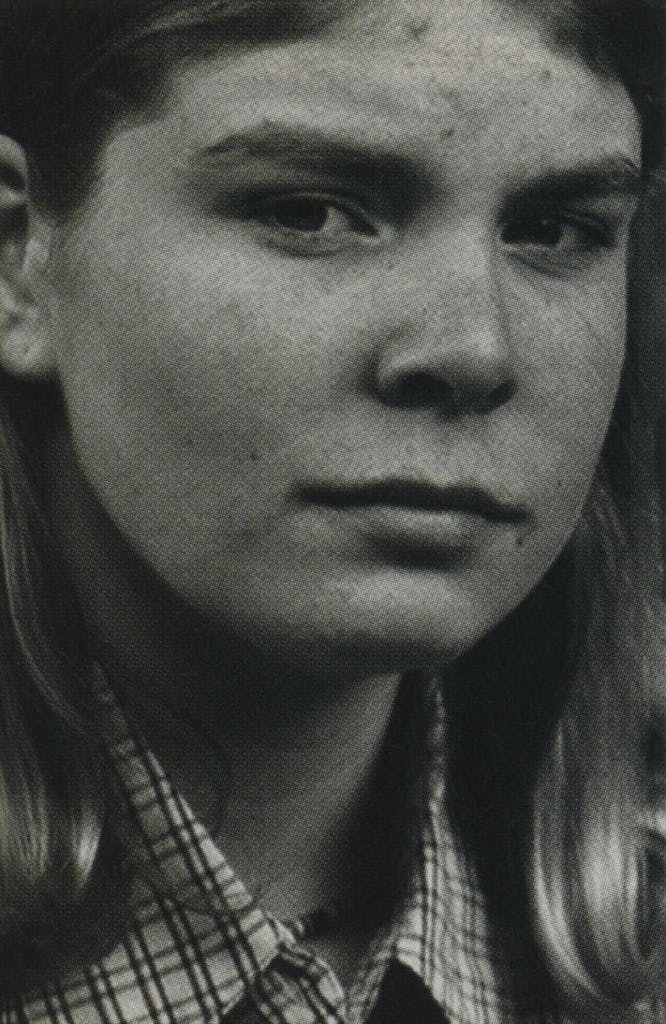

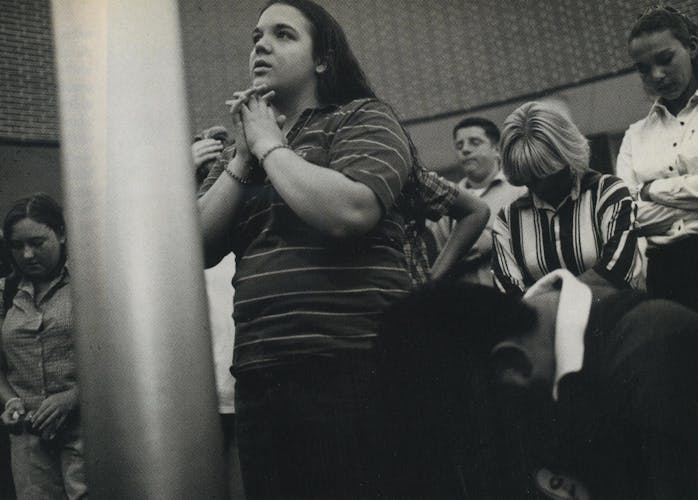

A Baptist preacher’s daughter, Marian would challenge the Fifth Circuit’s ruling by daring to pray over the school loudspeaker before a game, and at seventeen, there was no better standard-bearer for the cause. Her straight brown hair framed a round, serious face that betrayed no hesitations, and she felt passionately that the Doe suit was an affront to everything she believed. When the suit was filed, during her seventh-grade year, she wore Christian-themed T-shirts and carried her Bible with her to school, laying it across her desk as a silent protest. Now a student at the University of Arkansas, she recalled, “When I was sixteen, I decided to surrender my whole life to the Lord. I realized I needed Him, and I needed to surrender everything to Him, to serve Him to the utmost.” She spent the better part of her time in her father’s church, singing with the Praise Team and committing long passages of Scripture to memory. During her junior year in high school, she wrote an essay arguing that the educational system was wrongly promoting “the religion of humanism,” instead of a belief in God, by teaching “the humanist doctrine of evolution.”

As fate—or as some thought, divine intervention—would have it, Marian was the student chosen to deliver prayers before football games last fall. She had run for student speaker and finished second, but that September, she won by default after the winner stepped aside, putting her in both a legal and a moral quandary. By then, the Fifth Circuit had declared that pre-game prayer was unconstitutional, and though the school district was appealing the ruling, it had amended its guidelines accordingly. The speaker could still deliver an “inspirational message,” the school district allowed, but in accordance with federal law, prayers and references to a deity would be forbidden. For Marian, the new policy was the manifestation of all her fears about the Doe suit—namely, that it was trying to ban religious expression from public life. “I want to be able to express my religious faith, wherever I am,” she said. “If there is a religion that has been suppressed, it’s what a lot of people call evangelical Christianity. Christianity isn’t just an activity; it’s a state of being. It permeates every area of my life, and that’s why it’s such a problem when people don’t want me to express my religion publicly.” Her fears were compounded when, the Tuesday before the first Indians game, she was summoned over the P.A. system to report to the principal’s office. There, school administrators handed her the new rules governing pre-game messages. “The gist of the conversation was, ‘Look, we know you’re a good student, and we’ve never had any problems with you before, so we’re sure you’ll go along with the guidelines,’” she recalled. “It was very upsetting to me to realize that they wanted me to compromise my faith to ‘do the right thing.’” Several teachers took her aside that week and cautioned her not to offer a prayer before the game. One instructor she greatly respected pulled her out of class, wiping tears away as she urged Marian to “Render unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s.” An honor student who had always obediently followed the rules, Marian was overwhelmed. “Man’s law was trying to override God’s, and I could feel the emotional and spiritual strain of it,” she said. “I felt like I was involved in an intense good-versus-evil contest, almost a battle between God and Satan.”

Publicly, she kept her intentions hidden, but privately she typed out what she hoped to say that Friday, titling it “What the World Is Waiting to Hear.” Rumors abounded that if she prayed, she would be arrested, and Marian—not usually rattled—called her parents from school, distraught. “I felt physically ill,” she remembered. “I felt like a pawn in a chess game.” Seeking a compromise, the Wards met with Principal Gary Causey. To their dismay, he explained that Marian would be disciplined if she violated the new guidelines by leading students in prayer over the loudspeaker. Failing to see any other recourse, the Wards consulted with Houston attorney Kelly Coghlan, who filed suit on their behalf against the school district. Hours before the game, Coghlan won a temporary restraining order from U.S. district court judge Sim Lake preventing the district from punishing Marian if she prayed. “We wanted the school district, and the government as a whole, to treat Marian’s speech neutrally, so that if she said, ‘Let us have a safe game tonight’ or if she said, ‘God, let us have a safe game tonight,’ they wouldn’t discriminate,” said Coghlan.

The Ward case posed a legal conundrum: When students wish to pray over the loudspeaker before a football game, should their school allow them to do so in order to practice their religion freely, or forbid them to do so and thus avoid government participation in religion? The litmus test—named the Lemon test after the Supreme Court case Lemon v. Kurtzman—sets out that a government practice is unconstitutional if it lacks a secular purpose, advances or inhibits religion, or excessively entangles government with religion. Indeed, by any standard, the Santa Fe school district seemed excessively “entangled” by the time the Wards filed suit, having tried for several years to maintain a public forum for prayer and then putting restrictions on what could be said. Lost in Santa Fe’s fight for school prayer was a simple fact: Students are free to pray, individually or in groups, at any time. The courts’ concern begins only when prayer and government start to mix. (For example, football players may pray together before a game, but their coach may not lead them in prayer.) So why not simply abolish the pre-game speech altogether and allow students to pray on their own? “It’s a part of the game,” superintendent Ownby said. “Imagine if you went to church and there was no singing. It’s a long-standing tradition. We couldn’t take that away.”

The crowd roared at game time when Marian’s name was called, and as she ascended the stadium stairs in her green-and-gold band outfit to the press box, her hands shook and flashbulbs popped, the applause of four thousand people ricocheting off concrete. “I could actually almost feel the Lord carrying me, like a little kid,” she remembered. “I could almost feel his arms around me.” She asked all who wished to give thanks to God to bow their heads, and the crowd fell silent. “Lord, thank you for this evening,” she said, her voice gaining strength. “Thank you for all the prayers that were lifted up this week for me. I pray that you watch over each and every person here tonight, especially those involved in the game, that they will demonstrate good sportsmanship, Lord, and that we’ll have safety. Just be with the fans, that they will exemplify good behavior as well, Lord. And just be with each and every one of us as we go home to our respective places tonight. In Jesus’ name, I pray. Amen.” The crowd erupted in applause and stood for several minutes, cheering.

It was, in many ways, a portrait of the best of small-town life, of a community uniting to give thanks and to rejoice in the game that brought them together. And if not for the ugly scene that would take place when Marian repeated her prayer at homecoming several weeks later, during which fifty or so protesters were ridiculed and harassed, perhaps it would be easier to make the case for school prayer in Santa Fe. Its supporters argue that students in the minority—who do not wish to participate or who ascribe to a different religion—cannot be hurt by a profession of faith. “I cannot imagine how a prayer could do harm, especially a Christian prayer, because we’re all about loving people and being more like Christ, and Christ was the ultimate form of good and truth and right,” said Marian. School prayer advocates argue that those in the minority can choose not to listen or can step outside of a prayer gathering, without being stigmatized. But on homecoming night last fall, those who chose not to participate were indeed stigmatized, as has become commonplace for those in Santa Fe who dare to disagree.

Amanda Bruce, then a high school senior, was among the group of protesters. A practicing Catholic, she was angered that Marian Ward was delivering prayers that everyone in the stadium, regardless of belief, had to listen to. Amanda had already incurred a fair amount of hostility at Santa Fe High School for, among other things, speaking up in science class in support of Darwinism and against school-sponsored prayer. At the protest, she held a sign that said “I’m Not Protesting Prayer. I’m Protesting Discrimination,” but she was greeted with catcalls and jeers.

“Don’t you believe in God?” several passersby called out.

“You’re going to hell!” two girls cried.

“Devil worshiper!” a man spat from a passing pickup.

Others admonished her to pray. Across the street, a man holding a sign that read “Get the Devil Out of Santa Fe” shouted at protesters, warning them they were going to burn in hell. Amanda had expected that the protest would invite some hostility, but even she was taken aback. “The Bible is full of passages about how you shouldn’t judge others and how you should love your neighbor,” she said, “but the mood that night was hateful.”

THERE WAS PERHAPS NO MORE OBVIOUS an outsider in Santa Fe than Phillip Nevelow, the only Jewish student in the school district. The son of Galveston County sheriff’s major Eric Nevelow, who oversees the county jail, and Donna Nevelow, a sculptor, Phillip found his religion under attack—and his life threatened—during the fight for school prayer. The Nevelows had moved from Galveston to Santa Fe fifteen years earlier in search of more land for Donna’s quarter horses; they settled on a remote, ten-acre spread south of town and largely kept to themselves. Never venturing to a school board meeting, much less jumping into the fray over school prayer, they have now found themselves inadvertently at its center. “We would have to be deaf, dumb, and blind not to realize that what was happening to our son was a direct result of what was going on with the school district,” said Donna Nevelow. “A debate was raging over religion, and our son became the punching bag.”

An exuberant, if unremarkable, student who liked to sketch album covers in his notebook during class, Phillip seemed an unlikely source of controversy. But one afternoon in 1998 when Phillip, then twelve, was on lunch break in the schoolyard at Santa Fe Junior High, three students surrounded him and began chanting in a singsong voice, “Hitler missed one! No more Jews! Hitler missed one! He should have gotten you.” It proved to be only one in a series of cruelties he would have to endure. Last October a classmate scrawled a swastika in his notebook. In November another student cornered him in English class and saluted him while yelling, “Heil Hitler!” Later that month two boys drew swastikas on their hands and shoved them in Phillip’s face. Boys began roughing him up in the hallways and on the school bus, leaving dark bruises on his arms. His classmates were never reprimanded, the Nevelows said, and Phillip’s complaints to teachers and administrators were greeted with indifference. “By the eighth grade he’d developed what I call a defensive posture,” Donna recalled. “If he was attacked, he’d swing back.”

Donna herself did not fully realize the depth of hatred her son faced at school until one afternoon this past May, when she happened to be standing outside her house as the school bus pulled up. As Phillip stepped off the bus, Donna heard a student call after him—in a voice that carried over the dull roar of a backhoe a work crew was using—“Dirty Jew!” She stopped dead in her tracks. “I said, ‘Phillip, did they just say what I think they said?’ He said, ‘Come on to the house, Mom. Please don’t make a big deal out of this. Just come on to the house and ignore them.’” Renewed complaints to school administrators again resulted in no disciplinary action, said the Nevelows, and Phillip resumed his newly familiar stance—his shoulders hunched, his eyes fixed to the ground. Two weeks later he came home trembling with fear: Three high school students who often taunted him on the bus had been particularly unrelenting that day, proclaiming their hatred for Jews until the children sitting next to Phillip had to put their hands over their ears. Before he got off the bus, they had issued a chilling threat: “We’re going to hang you, you dirty Jew.”

Santa Fe police officers later arrested the three boys and charged them with making terroristic threats, but Phillip’s classmates continued to torment him. In June, while he waited for his mother to pick him up from summer school, a fellow eighth grader approached him. “So you’re the Jew,” the boy sneered. “I know someone who wants to kill you.” The boy shoved Phillip several times, then began to wrestle with him, eventually putting Phillip in a chokehold. A witness broke up the fight, and the police later charged the boy with assault. “We tried for a long time to work with the school, to get them to acknowledge that there was a problem and to rectify the problem,” Eric Nevelow said. “But the response was always a ‘boys will be boys’ attitude. [School board member] Robin Clayton even called what happened to my son ‘trite.’” In August the Nevelows transferred Phillip to a public school in Galveston and filed suit against the district, asking for payment for the out-of-district tuition and up to $4 million in damages. Given current litigation, superintendent Richard Ownby cannot comment on the case except to say, “We’ve only heard one side of the story.”

Was the hatred directed at Phillip simply adolescent cruelty or was it also the byproduct of the fight for school prayer? “I’m flabbergasted that anyone would make that connection,” said John Couch of the latter. “I can’t understand how a policy supporting an invocation before a game that advocates safety and sportsmanship could cause fights. I think it’s absurd.” It is striking that many prominent figures in the fight for school prayer scoff at the Nevelows’ claims, offering their opinion, not for attribution, that the family has blown these incidents out of proportion, or that Phillip—whom they have never met—is a troublemaker who must have provoked the fights himself. (“We heard he told kids that if they bothered him, he would use his Jewishness as a weapon,” one minister explained.) Rather than expound upon the importance of tolerance, town leaders seemed, at best, indifferent. When pressed about his opinion of the anti-Semitic remarks directed at Phillip, Couch said, “Obviously we don’t condone that, but the local media wants to make it look like Christians were behind this, and that is not Christian behavior. Christians seem to be fair game these days.”

The Nevelows readily admit that their son has had “battles and scrapes with other kids,” but they greeted assertions that he instigated anti-Semitic attacks with incredulity. Instead, they lay blame squarely on the shoulders of the school district, whose fight for school prayer, they believe, has fostered an atmosphere that puts religious minorities on the defensive. “Its insistence on Christian prayer in the schools has created an environment of hatred for anyone who is not a part of their agenda,” Donna said. “My son is living proof.”

NEARLY FIVE YEARS AFTER THE DOES filed suit, the battle that rocked this small Texas town to its core made its way to the Supreme Court, where nine justices sat in judgment this past March. At issue was a very narrow portion of the original case: Whether the school district’s pre-game policy endorsed prayer and violated the First Amendment or merely allowed a neutral forum for free expression in which a student could choose to say, or not say, a prayer before a football game. Aided by Texas attorney general John Cornyn, Jay Sekulow, the chief counsel of the American Center for Law and Justice, which was founded by televangelist Pat Robertson, represented the school district, arguing that its policy neither favored nor disfavored religious expression. Anthony Griffin, representing the Does for the ACLU, contended that the policy was adopted solely for the purpose of perpetuating public prayer at football games, and that, in practice, it coerced students at school-sponsored events to participate in religious exercises. “It endorses religion and its whole purpose is religion,” Griffin said, adding, “They weave a web and seek to have this court ignore its history.”

Reaffirming its earlier rulings against school-sponsored prayer, the Supreme Court ruled 6-3 in favor of the Does this past June. In the majority decision, Justice John Paul Stevens wrote that the district “asks us to pretend that we do not recognize what every Santa Fe High School student understands clearly—that this policy is about prayer. The District further asks us to accept what is obviously untrue: that these messages are necessary to ‘solemnize’ a football game and that this single-student, year-long position is essential to the protection of student speech. We refuse to turn a blind eye to the context in which this policy arose, and that context quells any doubt that this policy was implemented with the purpose of endorsing school prayer.” The policy, cautioned Stevens, “encourages divisiveness along religious lines” and “has the improper effect of coercing those present to participate in an act of religious worship.” He judged the policy to be lacking in secular purpose and therefore an unconstitutional government practice. “We recognize the important role that public worship plays in many communities,” Stevens wrote. “But such religious activity in public schools, as elsewhere, must comport with the First Amendment.”

Echoing the sentiments of many in Santa Fe, Chief Justice William Rehnquist wrote in his dissenting opinion that the ruling “bristles with hostility to all things religious in public life.” The court’s reasoning was flawed and contradictory, he wrote, observing that “sporting events often begin with a solemn rendition of our national anthem, with its concluding verse ‘And this be our motto: In God is our trust.’ Under the Court’s logic, a public school that sponsors the singing of the national anthem before football games violates the [First Amendment].” It is these subtle legal distinctions that rile school prayer supporters, who see the courts as irrational arbiters of that which is sacrosanct and who will not rest easy until the wall separating church and state has been breached. But it is such distinctions that protect religious freedom. As Justice Stevens concluded, “nothing in the Constitution as interpreted by the Court prohibits any public school student from voluntarily praying at any time before, during, or after the schoolday. But the religious liberty protected by the Constitution is abridged when the State affirmatively sponsors the particular religious practice of prayer.”

In the end, it was not school prayer in Santa Fe that proved so troubling as what the fight for school prayer wrought—branding those who disagreed as infidels. Perhaps the greatest irony of this town’s five-year crusade is that by fighting relentlessly for school prayer, Santa Fe revealed the true dangers of its argument, laying bare the need to keep religion out of government and, just as importantly, to keep government out of religion.

But between these two extremes, voluntary student prayer—as long as it is free of government intervention and truly student-led—can have a place in public schools. Indeed, despite considerable handwringing after the Supreme Court ruling, student prayer is very much alive and well, as was evident one morning in Santa Fe this September, when nearly seventy students gathered at dawn to give thanks to God. The sky was still a dusky gray when they massed around the school flagpole: Some knelt in supplication, while others bowed their heads, a few raising their hands skyward. Together, they stood in silent reflection, then joined in singing “Amazing Grace,” their reedy, uncertain voices slowly gathering strength. As students began straggling toward school from the parking lot, a few threw down their backpacks and entered the circle. In the shadow of a doorway, one teacher stood and watched, wiping tears away. At last, here was a prayer gathering that was truly and solely student-led. It was a moment for which all of Santa Fe could say amen.

- More About:

- Longreads

- High School

- Football

- Baptists

- Santa Fe