This story is from Texas Monthly’s archives. We have left the text as it was originally published to maintain a clear historical record. Read more here about our archive digitization project.

So what do you want, Henry?” president-elect Bill Clinton asked Henry Cisneros. It was mid-November, and Clinton and the members of his transition team, including Cisneros, were holed up in Little Rock, putting together the new government. The future of one Texan was already decided: Lloyd Bentsen would be appointed Secretary of the Treasury. Now Clinton set his sights on the other Texan he wanted in his Cabinet, the hesitant one.

“I’ve decided not to go back into government,” Cisneros said stoically. There was his sick son to consider and his new business venture. Clinton reached over and grabbed his arm. “Henry, come on,” purred Clinton in his warmest Elvis voice. “It’s just the two of us here. Level with me.” But the truth was that Henry Cisneros didn’t know what he wanted.

Thus began the latest in a series of psychodramas starring Henry Cisneros that have become a regular feature of Texas politics. Years ago it was, Would Henry eventually run for governor or senator? Then it was, Would Henry leave his wife, Mary Alice, for his campaign fundraiser, Linda Medlar? Next it was, Will Henry ever get back into politics? And now it was, Will Henry be Ann Richards’ choice to replace Bentsen in the U.S. Senate? But that question was superseded by the very one Clinton asked Cisneros: What do you want?

In Texas, there are only a handful of people who everyone calls by their first names—among them Ann Richards, Willie Nelson, and Henry Cisneros. What distinguishes these people from other famous Texans is that they aren’t one-dimensional to us. They are mega-people, because we’ve seen both their dark and their light sides on the public stage. Ann has had problems with marriage and alcohol, Willie has had problems with assorted marriages and the IRS, and Henry has had problems with his family and his future. These people are our icons, the repositories of our collective emotions and ambitions. We project our own reality onto them, creating their public selves, and then see it mirrored back. Ann is our matriarch. Willie is our outlaw. And Henry? Well, Henry is our reluctant and sometimes tragic prince.

I watched the Senate-versus-Cabinet process from both the inside and the outside. It was an agonizing ordeal, not just for Cisneros but for Richards as well. I have known Henry since his first term on the San Antonio City Council in 1975, and I once coauthored a book about him, so it wasn’t a surprise when he called on the last Saturday in November and said he wanted to talk about his choice between a Cabinet position and a possible Senate appointment. By then, Clinton was urging him to take a Cabinet job. I had heard from mutual friends that Henry was calling around, so I was ready with an opinion.

“Take the Senate,” I said and then listed the reasons. As a senator, he would work for himself, not Bill Clinton. Moreover, he would be building a political base at home in Texas, taking up where Bentsen left off in recommending federal judges, casting the Texas vote in Washington, and positioning himself to one day run for president. A few days later he called back. “The Senate appointment looks pretty good,” be told me, cheerfully. “I might get it.”

But of course that didn’t happen.

The drama that started in Little Rock with a tug on the arm would end a month later with the delivery of a small pink telephone message at the San Antonio International Airport. “Mr. Cisneros,” read the message, “please call Gov. Richards.” Cisneros knew that the time for a decision had come. Before he picked up the phone to return Richards’ call, he would have to know what he wanted to do.

All through November he had shuttled back and forth between Little Rock and Texas, serving on Clinton’s team and talking to Richards about the timing of Bentsen’s appointment to the Cabinet. By December, Bentsen was the official Treasury nominee and there was a strong possibility Cisneros would be offered Housing and Urban Development. But he and Richards were still talking about Bentsen’s vacated seat and getting nowhere. The question, from Cisneros’ point of view, was not whether he should take the Senate job but whether it would be offered. The answer to that question had as much to do with Richards as it did with Cisneros.

Several Richards confidants who were close to the selection process tell the same story. She wanted to give the Senate job to Cisneros, but she wanted to make sure his appointment wouldn’t blow up on her. The Lena Guerrero fiasco was on her mind. After having one appointment of a Hispanic backfire because of the character issue—Guerrero had to resign from the Texas Railroad Commission after admitting she had lied about having a college degree, and she was defeated for a new term—Richards couldn’t afford a repeat.

In the middle of November Richards set out to judge Cisneros’ electability. She held a private meeting with key Democratic contributors and asked who they thought should be named to the Senate vacancy. Cisneros had more support than anyone else. Then she conducted a series of voter focus groups to find out, among other things, if the public had forgiven Cisneros for his extramarital affair, which had been highly publicized. They had—provided that his marriage problems were indeed behind him. Finally, she wanted reassurance from Cisneros that he really wanted the job and had the necessary fire to fight for it.

Richards had good reason to doubt Cisneros’ desire. He doesn’t have a history of grabbing the brass ring. Cisneros has long been a statewide symbol of Anglo-Latino accommodation. For years people have been speculating that he would run for first one office and then another—comptroller, governor, senator, president. But when confronted with actually running, he always begged off.

Besides, the first time Richards talked to him about the Senate job, right after the presidential election, he told her that he didn’t see how he could do it because of the health of his five-year-old son, John Paul, who was born with no spleen and a life-threatening heart defect. The surgery to rebuild his heart is scheduled for June, shortly after a runoff for the Senate special election. Cisneros couldn’t spend four days a week in Washington and three days campaigning in Texas and feel that he had done right by John Paul. HUD was different: The surgery will be performed in Philadelphia, not far from Washington, and while the work load at HUD would be heavy, at least Cisneros would live in the same city as John Paul and see him at night. Nonetheless, Henry wavered as friends, relatives, and advisers all pressed him to reconsider. Mary Alice was among those urging him to run for the Senate. In the three years since Cisneros left the mayor’s job, Mary Alice had run and won an election for the San Antonio school board. During her own race, she found she enjoyed campaigning and looked forward to doing it statewide. “I’ll campaign in Texas while you’re in Washington,” she told him. “We’ll get through it.” So Cisneros decided to talk to Richards about it, half hoping she would convince him to take it.

Cisneros and Richards had a three-hour meeting December 1 at the Governor’s Mansion. According to a variety of sources, it was an odd dance. From Richards’ point of view, the purpose of the discussion was the vetting of Cisneros. She wanted to know what Clinton wanted to know—namely, what exactly it was that Henry wanted—except she had more riding on the answer than Clinton did. Richards needed to appoint someone who not only could win the special election in 1993 but also could help the Democratic ticket win in 1994, when she herself is up for reelection. To Richards, the central question was always whether Cisneros really wanted to make the race. She had learned from being grilled during the 1990 campaign about whether she had used drugs that unless you really want to win a high-profile election in Texas, it makes a whole lot of sense not to try.

Cisneros, on the other hand, was looking for a different kind of reassurance. In his soul he never really believed Richards would offer him the job. He kept looking to her for signs that she really wanted him. He read the newspapers, which reported she was considering him, state comptroller John Sharp, and former lieutenant governor Bill Hobby. The stories said he was the front-runner, but in his own mind Cisneros believed he was third. During the meeting, it was obvious he wanted the job, but being who he is—the reluctant prince —he wanted to be anointed. Richards being who she is—the queen mother—she wanted to see him fight. She never offered him the job, and he never asked for it. Had either spoken up, Henry Cisneros would be a United States senator today.

They went back and forth, examining the pros and cons of his running for the Senate. They talked about how he would handle questions about political and personal problems. It had been, after all, just a little more than a year since Mary Alice had filed for divorce, only to withdraw the petition a few weeks later. Cisneros told Richards that he and Mary Alice were reconciled and that they were prepared to face the press and public together. As Mary Alice told me when I interviewed her for this story, “Henry and I have put our problems behind us. What is past is past. We’re getting on with our lives.” It was clear to Richards, however, that Cisneros wasn’t looking forward to prolonged questioning by the media about his personal life.

The meeting dragged on, with each waiting for the other to make some kind of decisive move. Neither did. The closest Cisneros came to asking for the job was an offhand remark he made as he was leaving. “If you’re not going to give it to me,” he said to her, “would you give me a graceful way out?”

Into this vacuum of indecision stepped Clinton, who knew exactly what he wanted. The word out of Little Rock was that Cisneros was the first choice for HUD and there was no second choice.

“I think Henry would have taken the Senate job if she’d asked him,” said San Antonio mayor Nelson Wolff, who was talking to Cisneros regularly throughout this process. “Every day that passed without his getting an offer made him more nervous. In the end, he took the job that he was offered. ”

On December 6, the day of decision, Tony Sanchez, a wealthy Laredo oilman, investor, and political contributor, arrived at the San Antonio airport in his private airplane to pick up Cisneros and fly on to Little Rock for Clinton’s economic summit. Sanchez got Richards’ message first and handed it to Henry when he arrived with Mary Alice at the airport.

Henry looked at the message and told Sanchez, “We need to talk.” The two men and Mary Alice went into a small conference room at the airport. Cisneros told Sanchez, who had long been a member of his inner circle, that he was in agony over what to do. “If I go to the Senate,” said Cisneros, “I think I can win the election, but I just don’t know how I can physically do it with John Paul’s surgery. ”

“Henry,” said Sanchez, “I have no doubt that you can win the Senate race, but I will give you the advice my dad always gave me.” Henry could feel the room fill with emotion. Sanchez’s father, a pioneer in the oil business in South Texas, had died the previous spring. He and Cisneros had been close. “Take care of your family first,” Sanchez quoted his father, “and the rest will take care of itself.”

Cisneros lifted his head and stared hard at his friend. He seemed to be mulling over the wisdom of the ages. No one spoke for a long time. Cisneros understood that Sanchez was reminding him not only of his allegiance to John Paul but also of his reconciliation with Mary Alice, as well as some indefinable Latino bond. “If it’s okay with you,” Cisneros told his wife, “I’m going with HUD.” Mary Alice nodded, and Cisneros went into the next room. He returned Richards’ telephone call and gave her the news: He was out of the fight.

This is a new start for me,” Cisneros said in his silky smooth voice. “It’s like a rebirth.” It was his first week on the job as Secretary of HUD, and as he sat in his spacious tenth-floor office, straining forward in his desk chair with his heels dug deep into the tan carpet, one could hardly escape the conclusion that, for better or worse, Henry got the job he wanted after all.

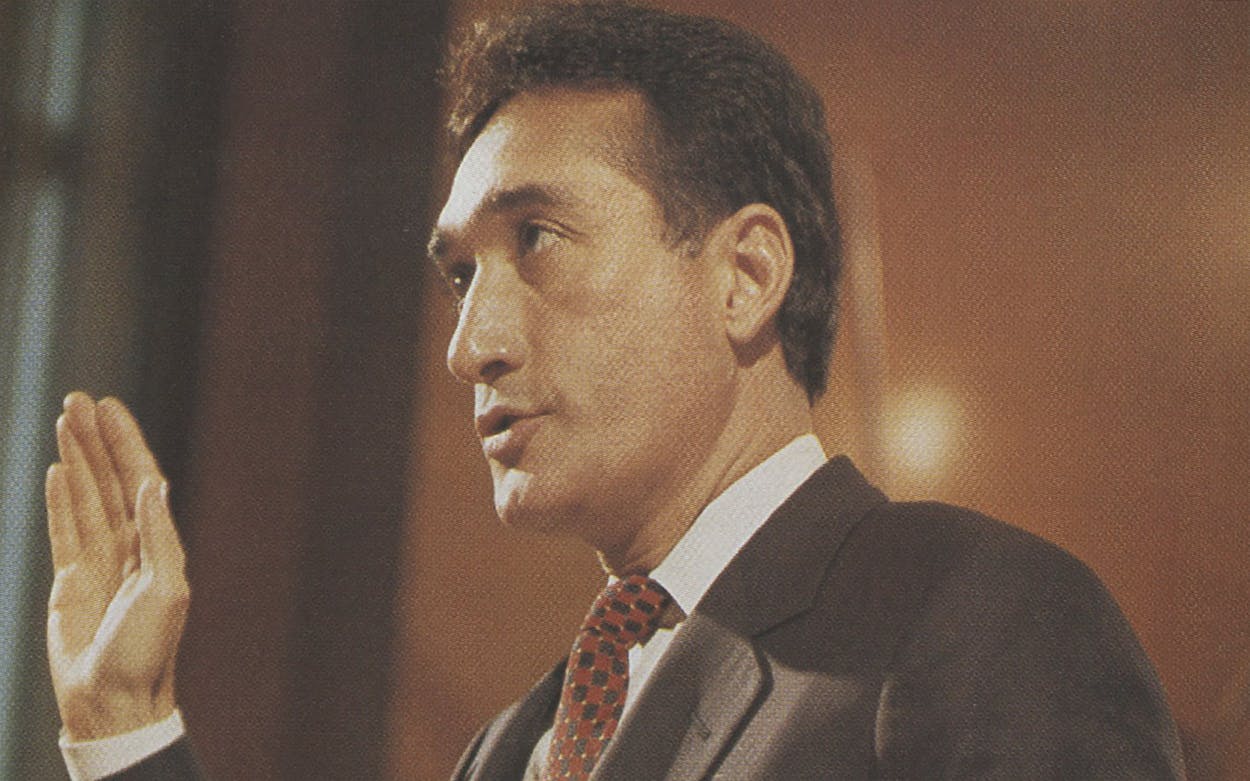

At 45, with the slightest bit of gray around his temples, and no longer the boy wonder of Texas politics, Henry is clearly more aligned with his original cherished ideal of himself—the public servant interested mainly in policy instead of an elected politician interested mainly in politics—than at any time since he first entered politics in 1975. He is in a new city with a new house and a new job. Three days on the job and his desk was already littered with list after list of projects he can do now, starting with an idea to convert decommissioned military bases into housing for the homeless.

But the grandiose aspects of his political persona won’t go away. Already all the networks have called for interviews, as have most major newspapers. In the middle of our interview, he stopped to take a call from Labor Secretary Robert Reich—“He’s the star of the Cabinet,” Henry confided—then a few minutes later his secretary popped in. Don’t forget to call Tipper Gore, she reminded him, and invite her to join him on tomorrow’s tour of a shelter for the homeless and for battered women. Suddenly, the poor and the homeless are glamour issues in Washington, and Henry is in the middle of them.

On the other hand, compared with the United States Senate, HUD doesn’t seem very glamorous. The building is a sixties monstrosity, a hulking concrete bunker built in a semicircle. It looks and feels exactly like a high-rise public housing project in any large American city. “Ten floors of basement” is the way one HUD worker described it to me. Standing in the HUD cafeteria, immersed in the smell of greasy pizza, I had a mental image of Bentsen, the other Texan in the Cabinet, signing trade agreements beneath glittering chandeliers in Geneva. “Poor Henry,” I thought to myself. “This place has all the comforts of Lenin’s tomb.”

One of the explanations I had heard in San Antonio for why Henry chose HUD was that it was less risky than running for the Senate. “He loves cinches,” one of his relatives told me. HUD sure doesn’t seem like a cinchy job to me. The agency has 13,500 employees, all but 115 of them civil servants whom Cisneros can’t easily fire. Many, no doubt, have grown accustomed to HUD’s failures. For years it has been a sleazy, scandal-ridden agency, a shameless dispenser of political pork, the worst job in the Cabinet. Reporters around Washington call it “the graveyard beat.” Things were so bad that some HUD officials were indicted on conspiracy, bribery, and mail fraud charges. Reagan’s appointee as HUD Secretary, Sam Pierce, acquired the unfortunate nickname “Silent Sam” because he was so invisible that Ronald Reagan did not recognize him at a White House function. Admittedly, the last Secretary, Jack Kemp, was able to institute some reforms and increase his own political currency during his four-year tenure. Kemp is now a front-runner for the 1996 Republican presidential nomination, so maybe there is life after HUD.

“I see myself as an apostle for cities,” Cisneros said, more cheerful than I had seen him in years. “I concluded that if I was going to sell my business, move the family up here, put myself back into public life again, then the only reason to do it is to do something I really care about. For me, that agenda is helping the poorest of the poor, making communities livable, and doing all within my power to avoid more pain in inner cities.”

Helping the poorest of the poor is something of a new agenda for Cisneros, who as mayor was aligned more with the working poor and business leaders interested in economic development. As he sees it, American politics changed last year with the Rodney King verdict and the subsequent riots in Los Angeles. Suddenly the problems of American cities—the divisions of race, the fear of crime, the loss of economic stability—became pressing issues. “What I saw in Los Angeles during the riots changed me,” said Cisneros. “I wanted to do anything I could to help. If Mayor Tom Bradley had offered me the job of deputy mayor, I would have packed up and moved to Los Angeles in a minute.”

Instead he has become America’s mayor. His strategy is do in other cities what he did as San Antonio’s mayor, only at increased velocity and volume. If he had taken the Senate job, he would have had to run for reelection up to five times in two years—the special election, a runoff, a possible Democratic primary and runoff in 1994, and a general election that fall—before he would have been able to really get down to the job.

Stylewise, he is like his eighties self. Delivering hot drinks and sandwiches to a homeless center in Washington, D.C., was a page out of an old book, reminiscent of times when he rode with San Antonio policemen, worked on a garbage truck, and even repaired potholes for a day. The first week at HUD, he worked the dreary halls like a political candidate in the heat of a campaign, stopping by various divisions to ask employees what they do, shaking hands, slapping backs, listening intently to what they had to say. One day he, Mary Alice, and John Paul ate lunch in the HUD cafeteria while employees stared at them with the same intense fascination as San Antonians who watched Henry and his family ride in Fiesta parades in a VW Beetle convertible.

Already Cisneros has in place two loyalists who will do for him at HUD what they did for him in San Antonio. Shirl Thomas, who guarded his front door in San Antonio, is doing the same at HUD, alerting him to problems within the bureaucracy and tracking the progress of must-do items on his work lists. Former San Antonio city councilman Frank Wing, John Paul’s godfather and Henry’s closest friend, is there to protect his back door, quietly working behind the scenes to disarm enemies and deliver bad news. Cisneros is notoriously bad at the underbelly work of politics—rewarding friends, punishing enemies, forging legislative coalitions, exerting muscle—and relies on Wing to play bad cop to his good cop. Oddly, most of Cisneros’ enemies have been Mexican Americans—ranging from the purely jealous to the ambitious and the ideological—and over the years it has been Wing who has derailed various “Stop Henry” schemes. In 1981, when San Antonio grocer Eloy Centeno wanted to run for mayor to draw Hispanic votes away from Cisneros, it was Wing who cut off strategic support to Centeno and averted his challenge. Later, when flamboyant councilman Bernardo Eureste and Cisneros feuded so publicly that Cisneros called Eureste the Prince of Darkness, it was Wing who negotiated a truce.

Now Wing must manage one of Cisneros’ oldest, most important, and least fruitful relationships—his not-quite-feud with longtime San Antonio congressman Henry B. Gonzalez. Henry B and Henry C are both from San Antonio’s West Side, but they are from different generations and have different styles, ambitions, and philosophies. In Henry B’s view, he is a man of principle and Henry C is a man of expediency. Shortly after Cisneros won election to the city council in 1975, he wrote Gonzalez, vowing, “I will never run against you.” Immediately Gonzalez wrote back, essentially telling Cisneros to tend to his own business. If destiny has always seemed to throw them together as rivals, never has the potential for confrontation been so great as it is now. As chairman of the House Committee on Banking, Finance, and Urban Affairs, Henry B has a stranglehold on what happens to HUD on the House side. Every bill Henry C proposes will have to go through Henry B. Every amendment to every item in HUD’s $26 billion budget will cross Gonzalez’s desk.

Personal temperaments aside, one need only drive south on Interstate 35 in downtown San Antonio to see that Gonzalez and Cisneros have wildly different views of how to save America’s cities. If you look to the left at the Florida Street exit, you will see the $184 million Alamodome, dreamed up and lobbied into reality by Cisneros with the help of a one half cent sales tax. The dome epitomizes Cisneros’ view of community development: massive public investment designed to generate private-sector jobs and profits. Look to the right at the Florida Street exit, however, and you will see Victoria Courts, one of the largest and oldest public housing projects in San Antonio. Row after row of red-roofed apartments epitomize Gonzalez’s more traditional view of community development. Before entering politics, he was a deputy director of the San Antonio Housing authority in 1950. Throughout his 32 years in Congress he has supported the 80 percent of HUD’s budget that goes for low-income housing.

“We have to do both,” said Cisneros, when I asked how he will reconcile his urban development view with Gonzalez’s housing view. Soon he was talking a blue streak, listing his first goals: “Number one, acknowledge the managerial mess that’s here. Number two, release about nine million dollars that I’ve already found up here for low-income housing.” Now there were two fingers in the air, and his voice crackled excitedly. “Number three,” he said, adding another finger, “move heaven and earth to find shelter for all these homeless people.

“I love this job already,” he told me. “It’s a comeback for me. It feels almost like redemption.”

So what does Henry want, really? For as long as I have known him, he has vacillated between seeing himself as an establishment politician and seeing himself as a hero to his people. As mayor he constantly moved between the two poles. I remember one breakfast at a San Antonio restaurant when he balanced his butter knife on the salt and pepper shakers. “All the pressure,” he said, “is on the bridge.”

Nevertheless, the bridge builder is the role Henry has chosen to resolve his own duality, and that, in the end, may have prompted him to take HUD. His greatest assets—his constant energy and ability to inspire—would be of little use in a slow-paced body besieged by interest groups. At HUD he is a bridge again, this time between the White House and the chaos of the streets.

It isn’t hard to figure out how Henry ended up as a bridge builder. If he took a standardized personality test, he would probably come out as an introvert masquerading as an extrovert. The introvert in him plays Chopin on the piano, studies the art and military maneuvers of ancient Greece, and dreams of writing a novel set in Mexico, while the extrovert, the part of him that loves sequential logic and reason, is exhilarated by the power of the bully pulpit.

He grew up in a cloistered world. He had a rigid Catholic education and a rigid Catholic upbringing. His mother insisted that he speak English, supervised daily household chores, allowed no television, and compiled lists for extracurricular reading. One summer he read 43 books. His father was a model civil servant, working his way up the ladder at Fort Sam Houston. The message was: Duty, honor, country, but always put others first. He left the cloister when he went to college at Texas A&M, and it was there that he came face to face with the Protestant’s message: Duty, honor, country, but always put ambition first. Internally, he is imprinted with the rhythms and values of two distinct minorities. He is both a Mexican American and an Aggie, and often it is difficult to tell which group has the greatest hold over him. As mayor, he would do his best work alone, late at night or on Saturdays in his office, with the “Aggie War Hymn” turned up full volume. “It would be so loud,” recalled Shirl Thomas, “that the walls would literally shake between our offices.”

When confronted with any kind of challenge, Henry always reverts to his mother’s drive, his father’s devotion to organization, and his own Catholic ghosts. There is a phrase in the Mass that he has taken to heart. It says: “Lord, I am not worthy that you should come unto me, but just say the word and my soul shall be healed. ” He believes that. A part of him has never been able to grasp or accept how important a political figure he really is, how many people look to him as someone who can find consensus among warring races, classes, and ideas. Instead, he always anticipates the worst. He spent $400,000 to win reelection as mayor—with 92 percent of the vote. He prepared for his HUD confirmation hearing, which turned out to be a love fest, as though it would be held before a firing squad.

Even now his admirers tell me that Cisneros is on the George Bush path to the presidency, that he will get there by route of the executive branch, not the Senate. The scenario is that he’ll do a good job at HUD, get a better job—maybe Secretary of State—next time around, ascend to the vice presidency, and then when he is 56 or even 60, he’ll run for president. Maybe so, but I doubt it. He is the same age now that Bill Clinton was when he decided to challenge an incumbent who had an 85 percent approval rating. I don’t see that kind of hunger or ambition in Henry. “It’s possible,” he said, from the safety of his cloister at HUD, “but I’m not going to do any of the things that would be called traditional political preparation.”

I told him the view of conventional political strategists and players back in Texas: that he walked the Senate fight, that when he had to make a decision, the man of the people feared the public’s referendum. “They say you’re a wuss,” I told him.

Henry shook his head and laughed. “Why does anybody care?” he asked.

Why, indeed? In choosing HUD over the Senate, the private Henry Cisneros, who wants to be the hero of his people, won out over the public one, who wants to be an establishment politician. “If I was wrong, I made the call myself,” he said, “and I believe I made it for the right reasons.” He acted not on the basis of what was best for Texas or for his enchanted public, but on the basis of what was right for him personally. For the first time in a long time, Henry got what Henry wanted.

- More About:

- Politics & Policy

- TM Classics

- Longreads

- San Antonio