My mom, Deborah, passed away in May.

It wasn’t COVID-19. Complications of complications from the cancer that she was cured of years earlier compounded in her body until she just needed to rest. She died in the hospital, and my sister and I weren’t even allowed in the building.

Over the past few years she had given away or thrown out many of her belongings. She left a house full of furniture with my ex-stepfather, and four years ago, when she decamped from Texas for her native New Mexico, she tossed out mountains of old papers and clothes that no longer fit her new, gaunt body.

She had been taken to the hospital many times over the past decade in various states of distress. A small bladder infection could throw her body into crisis; a fever, then pneumonia, then a dropping red blood cell count and hypoxia-induced confusion. No matter how bad it got, she was usually able to shake the problems off after a month and was back in the Sandia Resort & Casino bingo hall a few weeks after discharge.

In February, she was admitted again. At first, her brothers and sisters were by her side constantly. But after the coronavirus hit, visitors were banned, and she spent her days alone, trying to figure out how to place video calls so she could see my baby daughter. By the time she was discharged in April, we had decided she would move in with my family in Austin.

Before she left Albuquerque she and her sister spent hours discarding clothes, jewelry, and shoes. Then two of my cousins drove a van full of furniture and boxes filled with her smaller possessions to Austin in one twelve-hour push. On the way, they were shocked by the number of people they saw at gas stations who weren’t wearing masks.

After they arrived, my cousins and I unloaded the truck and stacked everything in a storage unit. We wore masks and were afraid to hug. We unloaded boxes of old CDs; bins and bins of photographs; a single-cup coffee maker; framed paintings and photographs; old patio furniture; a living room set; a dining table; pots, pans, and dishes; untold numbers of hand towels and throw pillows; dozens of Santa Claus figurines that she’d spread across her home every November and leave up through January at least; and so much more.

A week later, my mom deplaned at Austin-Bergstrom International Airport with legs too swollen to walk on and an oxygen cannula that kept slipping out of her nose. She had two suitcases and a carry-on, all of which rattled when lifted. They each held dozens of pill bottles split into blurry categories: active prescriptions, old prescriptions, take as needed, and empty and in need of refill.

She had been with us for only a week when another infection took hold. Her oxygen saturation dropped, and she started to see people who weren’t there; I made sure she kissed my daughter twice before we took her to the hospital. She almost pulled through; her breathing and blood pressure stabilized, which seemed encouraging. But then her kidney function cratered, and, after she’d spent five days alone in the ICU, her heart stopped beating. She was gone.

My sister and I will split up or give away most of Mom’s stuff. We’re not going to cherish her washcloths and the cheap necklaces bought from friends in the bingo hall. The clothes don’t fit my sister or my wife, so they’ll be donated. The furniture will go to an organization that helps people in need. We’ll keep the pictures, of course, but they’ll probably stay in a box until we get around to buying a photo album.

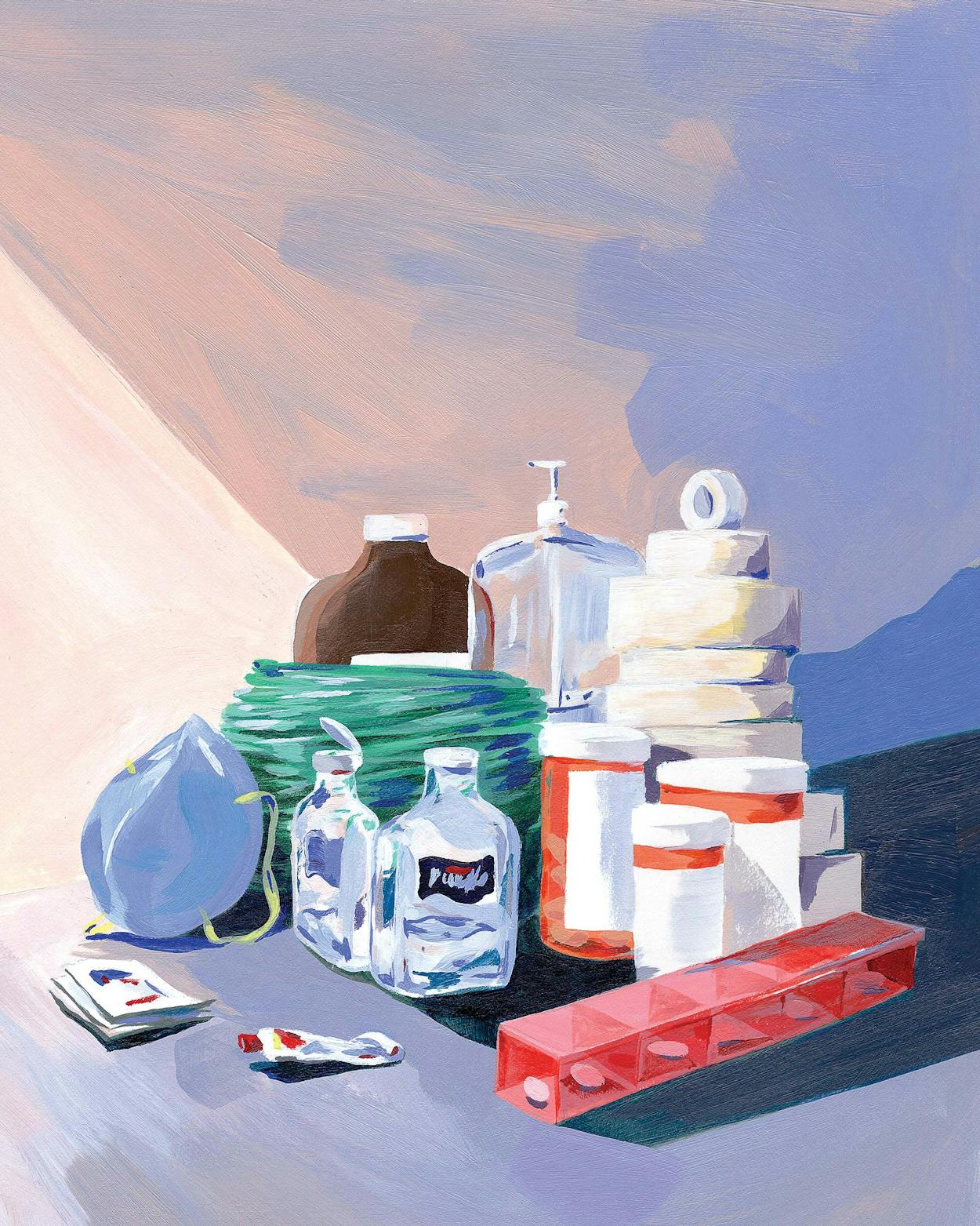

But that’s not all my mom left behind. After every hospital stay she was sent home with a small mountain of supplies that accumulated for years until, at the end, they were boxed up and shipped to Texas. Now they’re mine.

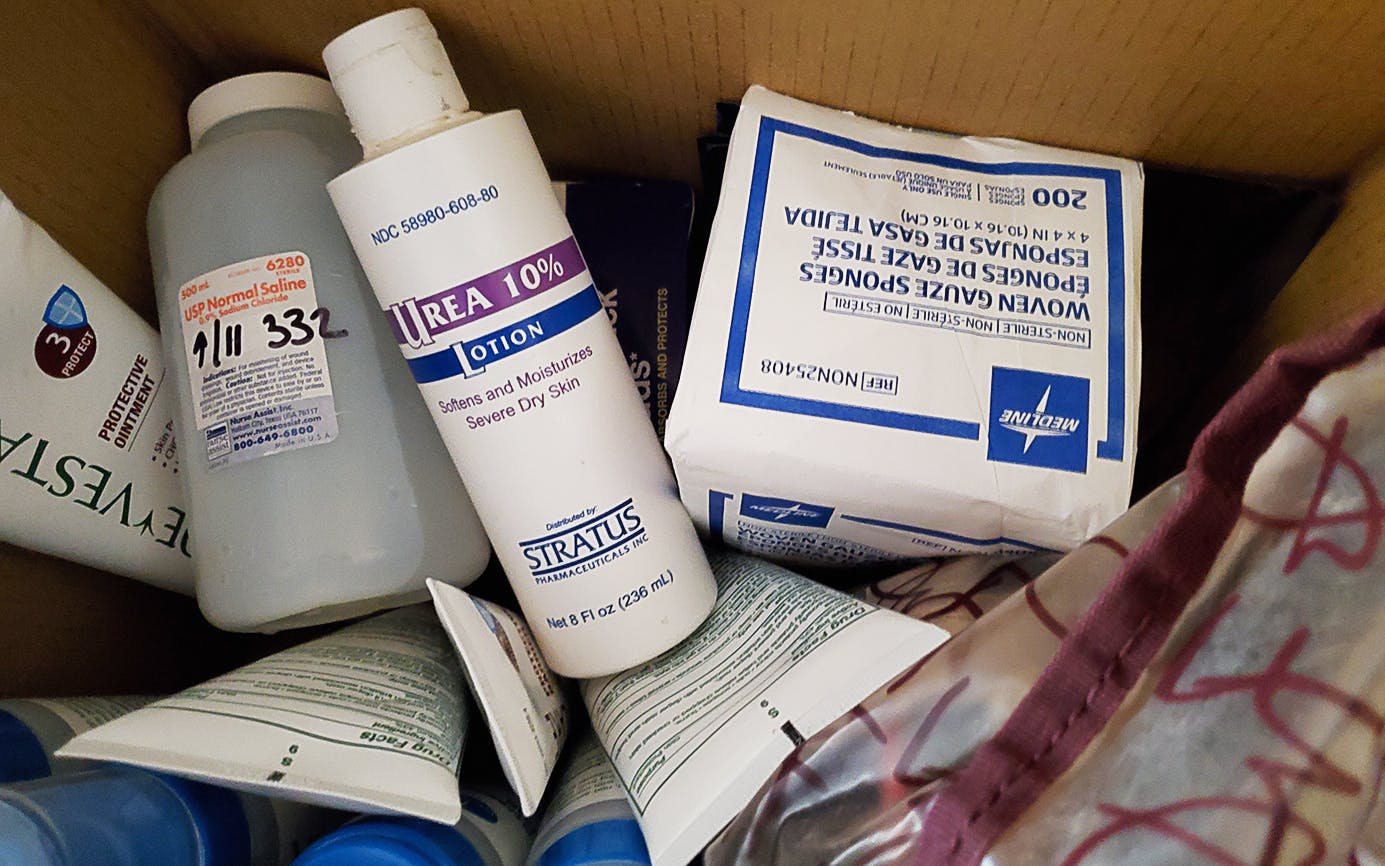

Our haul included: one Karman LT-980 Ultra Lightweight folding wheelchair, one Inogen One G4 portable oxygen concentrator, one BodyMed two-button folding walker, one Drive four-wheeled rollator walker with fold-up removable back support, one tube of Stratus Urea 10 percent lotion, two 10-foot gait belts, three canes (unused), three sheets of Curad Xeroform petrolatum dressing, three boxes of two hundred woven gauze sponges, four 2-ounce bottles of Hollister m9 odor eliminator spray, five 8-ounce bottles of Aloe Vesta protective ointment, six 8-ounce bottles of Aloe Vesta cleansing foam, hundreds of sterile alcohol prep pads, Salter Labs green crush-resistant three-channel tubing of various lengths, multiple rolls of medical tape, and stacks and stacks of wipes, chuck pads, bandages, N95 masks, and latex-free examination gloves.

And hundreds and hundreds of pills: prednisone, Cipro, lorazepam, folic acid, iron, pantoprazole, budesonide, carvedilol, levothyroxine, benzonatate, acyclovir, dapsone, rosuvastatin, montelukast, tolterodine, pregabalin, and fluconazole, among many others.

My vivid strain of apocalyptic thinking, sharpened by the coronavirus pandemic, makes me want to hoard my dead mother’s medical supplies. If toilet paper, yeast, and flour can go missing from shelves, then what hope do we have for antibiotics? What if the hospital system is overwhelmed and one of us needs oxygen? Would we pass the cannula back and forth in front of our fireplace as we wait for the power to come back on? Might the antiseptics, bandages, and gauze help us avoid waiting for hours in an overcrowded, plague-ridden emergency waiting room? Would the prednisone give us the boost of energy we’d need to wait in a rations line after another sleepless night with a howling, hungry baby?

Maybe all of these fears are ridiculous. Maybe we won’t actually run out of food and need the prescription iron supplements. Maybe we won’t trade expired antibiotics for clean water. But what if we do? A couple of boxes of supplies tucked away in the back room seem prudent. What if we lose our jobs and can’t afford the most basic necessities? The hospital cleaning foam would be perfect for our teenage boys, who barely use soap anyway.

My wife and I will (fingers crossed) get old. We’ll likely need canes and walkers and wheelchairs. How much more will they cost on the medical black market in three decades? In mid-March, I had engaged in some light hoarding of toilet paper, frozen pizza, and white wine, which seemed prudent then, if a bit silly in retrospect. But this equipment could save our lives. My mother had at least a dozen half-full travel-size containers of hand sanitizer, which basically means we’re rich.

I don’t think any of us will look at surplus the same way again. How many of us will buy a little extra tuna every week? Maybe stash some cans in the back of the pantry or inside a plastic bin in a back closet that we’re embarrassed to admit even exists?

Still, in moments of clarity and hope, which usually accompany waking up my toothy and grinning thirteen-month-old daughter, I realize that the demands of the present are more pressing than my fears of the future. And that meeting those demands—enjoying them, even—might make that bleak future a bit less likely.

So the pills get dropped off at a pharmacy; it takes me five minutes to shove each bottle through the narrow slot of the medicine disposal bin. The gait belts, the oxygen concentrator and hoses, and the walkers, canes, and wheelchairs are donated to a local group that supports people with ALS. The soaps and lotions and tiny tubes of toothpaste are made into gift bags for those camped out under overpasses.

It’s possible I will regret this charity. Yet I don’t want to give in to that darkness. It’s not naive to trust that society will still be here tomorrow. Each donated piece of equipment, each relinquished antibiotic, each handed-out bandage and disinfectant is more than an act of charity. It’s an act of optimism.

As I’m typing this very sentence, my daughter is waking up from her morning nap. I can hear her babbling to her pink fuzzy bunny, which she refuses to sleep without and which my mom bought her weeks before she was born. Part of me will always want to keep every useful scrap I find, but I’m giving this stuff away for her.

Austin writer Richard Z. Santos is the author of the novel Trust Me and a vice president of the National Book Critics Circle.

- More About:

- Austin